[Lithography] superseded copper and wood engraving, for these are lengthy processes: and the times were restless and hurried and out of breath, as if pursued by fashion and taste – as if fearing that the truth of the morning had already become a lie – and so they needed a quicker method of reproduction.5As a technique with no previous history, lithography freely embraced a wide range of subjects, including contemporary topics traditionally shunned by the fine arts which ranged from military episodes to fashionable dress.6 While the new medium acquired artistic credibility by reproducing Old Master and modern history paintings—these were the main type of lithographs displayed at the Paris Salon exhibitions—lithography moved quickly into a commercial realm of image production, distribution and sale.7 Some lithographs, like the Grévedon series, occupied an intermediate, porous zone between the fine arts and the commercial arts that a number of dealers, editors, and entrepreneurs attempted to open up in the 1820s and 1830s.8 New forms of image production such as Henri Grévedon’s Le Vocabulaire des dames (1831-1834) so far have been little discussed in the scholarly literature. Beatrice Farwell first drew attention to the subject type in her survey of popular lithography, classifying it under “Pinups and Erotica,” quite differently than I do here.9 Such series merit reconsideration for several reasons. Firstly, these lithographs laid claim to a certain status as fine art in ways that overlap interestingly with their distribution and sale through commercial channels. Grévedon’s prints, especially hand-colored examples, imitated the format and look of oil portraits at the same time that they visualized fantasies about fashion in ways that fine art painting as a medium could not do. The serial form of the images and their interaction with caption texts are features that belong in this epoch to the world of print. Secondly, the lithographs refer to and deploy language in intriguing ways. The titles of this and other series allude to linguistic components such as “vocabularies” and “alphabets,” which suggests a role for the images as a kind of visual primer of style. Captions situated below the images involve the viewer in an imaginary exchange of dialogue, and the open-ended associations they evoke laid the groundwork for the kind of “written fashion” that Roland Barthes analyzed in his seminal study of semiotics, The Fashion System (1967; trans. 1983). Thirdly, these prints were symptomatic of larger tendencies in image production at the time. The contours of this commerce are familiar to specialists of prints and other reproductive media but bear recalling for the understudied period when the speculative commercial character of lithography was in formation. The proliferation of such prints went hand-in-hand with a standardization of the images according to a complementary dynamic of production that has implications for how we think about the author-function associated with them. Between fine and commercial art Grévedon’s Le Vocabulaire des dames (1831-1834) exemplifies the artistic pretentions of a new genre of lithograph that appeared in the late 1820s and early 1830s. The prints are large, measuring 48.5 (H) x 31 (W) cm (19 x 12 1/8 in.).10 These folio dimensions made them much too big for insertion in albums and “keepsake” books, which were usually octavo in format, 20 to 25 cm (8 to 10 in.) (H) or smaller, though folio keepsakes are known.11 Grévedon’s prints were issued in four livraisons of six prints each over four years and could be purchased as subsets or as a series; the publisher did not advertise single sheets for sale. The impressive size of his lithographs might have made them suitable for framing as wall images, and leading print sellers sold gilt-edged mattes and glass cut to standard sizes “for framing engravings.”12 Alternatively, they could be bound into a dedicated folio album, and a complete leather-bound set of twenty-four hand-colored plates survives in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library.13 Deluxe hand-coloring significantly increased the price. The black-and-white edition of Le Vocabulaire des dames sold for 9 francs per livraison (a unit price of 1,50 francs) and hand coloring nearly doubled that price, to 15 francs per livraison (a unit price of 2,50 francs). Other print sellers charged double or more for hand-colored lithographs.14

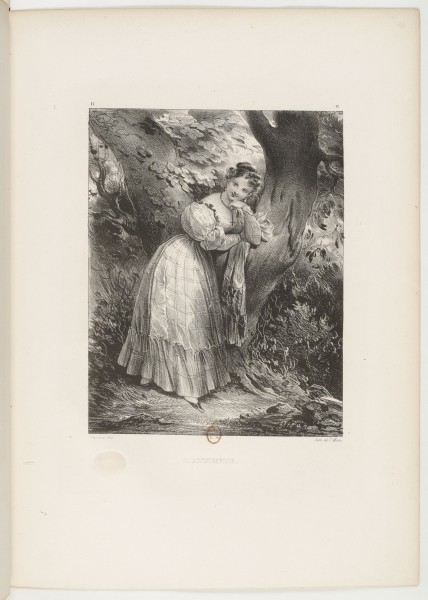

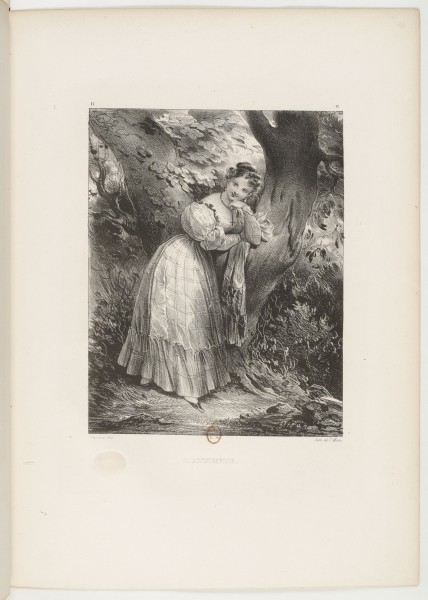

![Fig. 1. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 1, Peut-Être | [Perhaps], Paris: Rittner and Goupil and London: Charles Tilt, 1831-34, album of 24 hand-colored lithographs on wove paper, 48.5 x 31 cm (19 x 12 1/8 in.) (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Mass.).](https://nonsite.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1-Grevedon-Vocabulaire-des-Dames-1832-no-1-Peut-etre-Clark-TIFF-404x600.jpg) Fig. 1. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 1, Peut-Être | [Perhaps], Paris: Rittner and Goupil and London: Charles Tilt, 1831-34, album of 24 hand-colored lithographs on wove paper, 48.5 x 31 cm (19 x 12 1/8 in.) (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Mass.).

Fig. 1. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 1, Peut-Être | [Perhaps], Paris: Rittner and Goupil and London: Charles Tilt, 1831-34, album of 24 hand-colored lithographs on wove paper, 48.5 x 31 cm (19 x 12 1/8 in.) (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Mass.). Fig. 2. Petit courrier des dames, 1828, no. 530, “Modes de Paris,” hand-colored ngraving on wove paper, 22 cm. (H). (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Mass.).

Fig. 2. Petit courrier des dames, 1828, no. 530, “Modes de Paris,” hand-colored ngraving on wove paper, 22 cm. (H). (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Mass.). Fig. 3. Antoine Trouvain, Françoise d’Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, ca. 1691, hand-colored engraving on paper, 29 x 19 cm.

These large lithographs were thoroughly conversant with the conventions of fine art portraiture at the level of conception, which had not always been the case for the relation of popular prints to paintings. Grévedon adopted the format of half-length oil portraits for his prints (Fig. 1), a format which itself gained favor in the romantic period, perhaps because it focused instead on the shaped torso and dressed head and avoided draping the legs, which had been a distinctive feature of neoclassical portraiture. The half-length format of these lithographs deviated from the conventions of the fashion print, which depicted full-length, usually standing figures (Fig. 2). The earliest French fashion prints, produced from the last quarter of the seventeenth century on the rue St. Jacques in Paris by engravers such as Nicolas Arnoult and the Bonnarts (Fig. 3), were worlds away from the sphere of fine art production and were fundamentally ignorant of techniques of portrait painting.15 The separation between fine art and popular prints remained in place through the early nineteenth century but lithography, which was promoted as an artist’s medium, began to make inroads into that divide. Printmakers began to imitate paintings at the same time that certain painters looked to fashion prints for ideas and even supplied drawings to fashion journals.16 By the 1830s, it was not always clear which medium was influencing the other.

Henri Grévedon (1776-1860) offers a case in point since he trained as a painter before taking up lithography. He studied history painting with Jean-Baptiste Regnault at the beginning of the century and subsequently specialized in portraiture, making his career outside France between 1804 and 1816.17 After returning to Paris he continued to make accomplished oil portraits, such as Portrait of a Young Woman ([1820s], Musée Magnin, Dijon), but concentrated on lithography after 1822. The medium was on the cusp of commercialization and Grévedon was well prepared to handle the black lithographic crayon by the technique of manière noire drawing, noted for its velvety tonal gradations, which he had learned in England. Grévedon’s turn to the new medium was probably economically motivated but, following his experience with engraving, he must have appreciated seeing rapid results and recognized its appropriateness to the subject matter that interested him.

Fig. 3. Antoine Trouvain, Françoise d’Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, ca. 1691, hand-colored engraving on paper, 29 x 19 cm.

These large lithographs were thoroughly conversant with the conventions of fine art portraiture at the level of conception, which had not always been the case for the relation of popular prints to paintings. Grévedon adopted the format of half-length oil portraits for his prints (Fig. 1), a format which itself gained favor in the romantic period, perhaps because it focused instead on the shaped torso and dressed head and avoided draping the legs, which had been a distinctive feature of neoclassical portraiture. The half-length format of these lithographs deviated from the conventions of the fashion print, which depicted full-length, usually standing figures (Fig. 2). The earliest French fashion prints, produced from the last quarter of the seventeenth century on the rue St. Jacques in Paris by engravers such as Nicolas Arnoult and the Bonnarts (Fig. 3), were worlds away from the sphere of fine art production and were fundamentally ignorant of techniques of portrait painting.15 The separation between fine art and popular prints remained in place through the early nineteenth century but lithography, which was promoted as an artist’s medium, began to make inroads into that divide. Printmakers began to imitate paintings at the same time that certain painters looked to fashion prints for ideas and even supplied drawings to fashion journals.16 By the 1830s, it was not always clear which medium was influencing the other.

Henri Grévedon (1776-1860) offers a case in point since he trained as a painter before taking up lithography. He studied history painting with Jean-Baptiste Regnault at the beginning of the century and subsequently specialized in portraiture, making his career outside France between 1804 and 1816.17 After returning to Paris he continued to make accomplished oil portraits, such as Portrait of a Young Woman ([1820s], Musée Magnin, Dijon), but concentrated on lithography after 1822. The medium was on the cusp of commercialization and Grévedon was well prepared to handle the black lithographic crayon by the technique of manière noire drawing, noted for its velvety tonal gradations, which he had learned in England. Grévedon’s turn to the new medium was probably economically motivated but, following his experience with engraving, he must have appreciated seeing rapid results and recognized its appropriateness to the subject matter that interested him.

Fig. 4. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 10, I Wish I Could. | Je le voudrais.

Fig. 4. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 10, I Wish I Could. | Je le voudrais. Fig. 5. Louis Hersent,Portrait of Madame Arachequesne, 1831, oil on canvas, 84 x 65 cm. (Musée Carnavalet, Paris). Photo: Roger-Viollet / Parisienne de la Photographie, Paris.

The concept of fashionability that lithography and painting shared around 1830 can be gauged through a comparison of plate 10 from Grévedon’s Le Vocabulaire des dames (Fig.4) and Louis Hersent’s Portrait of Madame Arachequesne (1831; Paris, Musée Carnavalet) (Fig. 5). Both works present half-length figures of stylishly dressed women set against nondescript backgrounds. Both exclude hands from the pictorial field, limiting corporeal expression to the heads and the torsos. In these truncated, gestureless bodies, the costumes the women wear—fabulous hats and shaped bodices—vie for visual attention. Grévedon’s publishers, Rittner and Goupil, called his figures “portraits,” which implies the portrayal of individual likenesses, while simultaneously acknowledging their fictional character by advertising them as “portraits de fantaisie.”18 There was considerable interplay between portraits and imaginary figures in prints and paintings of this period, including in other lithographs by Grévedon, although Le Vocabulaire des dames consists entirely of ideal types. These “pretty women,” as Beatrice Farwell called them, are invariably young, with oval faces, regular features, white skin, and brunette hair, flawless sloping shoulders and tiny waists.19

Fig. 5. Louis Hersent,Portrait of Madame Arachequesne, 1831, oil on canvas, 84 x 65 cm. (Musée Carnavalet, Paris). Photo: Roger-Viollet / Parisienne de la Photographie, Paris.

The concept of fashionability that lithography and painting shared around 1830 can be gauged through a comparison of plate 10 from Grévedon’s Le Vocabulaire des dames (Fig.4) and Louis Hersent’s Portrait of Madame Arachequesne (1831; Paris, Musée Carnavalet) (Fig. 5). Both works present half-length figures of stylishly dressed women set against nondescript backgrounds. Both exclude hands from the pictorial field, limiting corporeal expression to the heads and the torsos. In these truncated, gestureless bodies, the costumes the women wear—fabulous hats and shaped bodices—vie for visual attention. Grévedon’s publishers, Rittner and Goupil, called his figures “portraits,” which implies the portrayal of individual likenesses, while simultaneously acknowledging their fictional character by advertising them as “portraits de fantaisie.”18 There was considerable interplay between portraits and imaginary figures in prints and paintings of this period, including in other lithographs by Grévedon, although Le Vocabulaire des dames consists entirely of ideal types. These “pretty women,” as Beatrice Farwell called them, are invariably young, with oval faces, regular features, white skin, and brunette hair, flawless sloping shoulders and tiny waists.19

Fig. 6. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 8, Je ne Veux Pas | I Will Not.

Fig. 6. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 8, Je ne Veux Pas | I Will Not. Fig. 7. Théodore Chasseriau, Portrait of Aline Chasseriau, 1835, oil on canvas, 92.4 x 73.6 cm. (Musée du Louvre, Paris).

Fig. 7. Théodore Chasseriau, Portrait of Aline Chasseriau, 1835, oil on canvas, 92.4 x 73.6 cm. (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Fig. 8. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 24, IL EST GENTIL! | HOW AMIABLE HE IS!

It is instead the manner of dressing that realizes the prints’ claim to the individualization of portraiture. One elegant costume and striking coiffure follows another through twenty-four plates, each different from the other. This parade of outfits fulfilled the “fantasy” of dressing up promised by these “portraits de fantaisie.” Costume had always been the primary vehicle of fantasy in “portraits de fantaisie,” a genre of painting that included seventeenth-century Dutch tronies and Italian teste capriciosi through eighteenth-century English fancy pictures and Jean Honoré Fragonard’s famous series of some fifteen “portraits de fantaisie” (c.1769).20 These precedents exploited the transformative potential of costume, its ability to change people’s identities by dressing them in regional, foreign, or historical garb. Le Vocabulaire des dames, by contrast, muted that potential for the extraordinary by bringing the clothing portrayed into line with contemporary fashion: the outfits shown range from normative cosmopolitan to mildly exotic and historical, nothing too outlandish. The overwhelming majority are respectable daydresses, such as the brown pelerines, or dresses with matching capes, depicted in plates 8 and 16 (Figs. 6 and 18), which closely correspond to the one worn by Aline Chassériau in her brother Théodore’s 1835 portrait of her (Fig. 7). A few outfits incorporate more whimsical historical and exotic elements such as the jaunty seventeenth-century-style hat and fur-trimmed vest shown in Vocabulaire plate 24 (Fig. 8), and that blending of exotic motifs into the dominant contemporary silhouette was typical of the fashion and costume subjects depicted in prints of the 1830s.

In Hersent’s Portrait of Madame Arachequesne, by contrast, the sitter’s facial expression is emphasized at the expense of the clothing. One would expect this in an oil portrait though not to the degree of animation exhibited by Madame Arachequesne. Unlike most portrait sitters, who look solemnly out at the viewer with a studied lack of expression, Madame Arachequesne turns her head to one side and looks up, her lips slightly parted. This kind of angled upward glance was typically reserved for writers and musicians since it signified inspiration or rapt attention; Hersent himself had used it in his earlier portraits of the poet Delphine Gay and the writer Sophie Gay (both, 1824, Musée national du château, Versailles). In the absence of information about Madame Arachequesne, we can only observe that her expression lends her features an unusually emotive, genre-like character.21 Facial expressions of this kind, though unusual in oil portraits, were common in lithographs of imaginary subjects such as plate 10 from Le Vocabulaire des dames (see Fig. 4), in which a woman tilts her head and looks up and out of the frame. These prints would have helped legitimate and popularize emotive and sentimental expressions for adoption in fine art portraits.

In contrast to the rich variety of clothing styles, colors, fabrics, and trimmings shown in Le Vocabulaire des dames, Madame Arachequesne wears a simple white dress. This choice harkened back to the monochrome neo-Greek dresses of earlier decades and conformed to an unwritten law of painting that clothing should not detract from the face. Madame Arachequesne’s white dress, while elegant and up-to-date in its styling, was a conservative choice in pictorial terms. The main concessions the portrait made to fashionability are the sitter’s wide-brimmed straw hat decorated with red poppies and a wide belt that accentuates her slim waist. Neoclassical fashion had so valorized the undressed head that it remained unusual in the 1820s for women to wear hats in oil portraits, as the Portrait of Aline Chasseriau demonstrates (see Fig. 7), despite their revival in sartorial practice. Printed images, on the other hand, featured elaborate hats (see Fig. 2). Hersent’s painting resembles Grévedon’s lithographs as well as periodical fashion plates in making the hat into its crowning glory. In the interests of expressive effect both the painting and the lithograph frame women’s faces with lavishly decorated hats, though the balance between the latter is different in each case. Madame Arachequesne’s large animated face dominates her pale figure and is accentuated by the eye-catching red poppies on her hat and transparent red shawl draped over her lower arms. In the lithograph, however, visual attention is divided between the woman’s feathered beribboned hat, which frames a small head, and her colored dress with its scalloped bertha, crossed bodice and white layered sleeves. The clothing and coiffure are more vibrantly rendered than her body, which accords a higher priority to inanimate over human subjects.

While common ground was shared by lithographic “portraits de fantaisie” and oil portraits in the 1830s, we attend to these works quite differently. Modern oil paintings presume a singularity of execution and sustained viewing attention whereas these lithographs were designed for rapid consideration. When bound into an album, the sequencing of the prints creates a momentum that carries the viewer forward. Their vignette format, floating on the page with ragged, unbounded edges that blend into the sheet, leads one on to the next page. Many of the captions invoke the comings and goings of a potential encounter — Viendrez Vous? [Are You Coming?], No. 5; or A bientôt. | I’ll See You Very Soon, No. 19 – as if commenting on the viewer’s transitory engagement with the figures pictured. This is very different from the momentum of narrative, which directs a reader toward a goal. Here, the viewer’s relationship to the images is casual and undirected; one can take them or leave them, linger over one or move on to another. If a lithograph was extracted from a set, it could easily become part of another context such as a décor, and it has been argued that captions gave prints a self-contained independence as wall images.22

Oil paintings demanded a different kind of visual attention. Much larger than Grévedon’s lithograph, Hersent executed his Portrait of Madame Archequesne as a pendant to Portrait of Monsieur Arachequesne, which the artist’s wife, Louise Marie Jeanne Hersent (née Maudit) had completed the year before (1830; Paris, Musée Carnavalet). Despite matching the existing half of a pair, Hersent treated the composition of his portrait separately from that of its mate.23 The poses of husband and wife only vaguely mirror each other, and Madame Archequesne’s sideways glance flies over her husband’s head and misses him entirely. Hersent also introduced a foliage background behind his sitter, which creates a different sense of space and texture from the plain ground in the pendant portrait. The foliage fills out the frame and slows viewing down: one attends to distinctions in facture between the brushily painted greenery and the smoothly painted dress and to subtle differentiations of hue such as the buttery yellow sash set off from the white dress. Hersent exhibited this portrait at the Salon of 1831, which suggests that such distinctions of facture, texture, and color were meant to be noticed and appreciated.24 In contrast, the Grévedon series was sold commercially, by subscription and through shops in Paris and London, and not exhibited at the Salon, even though other types of lithographs at the time were.

Images and Texts

Texts had been integral to printed images since engraving began in the sixteenth century though only rarely were they brought into a direct physical and conceptual relationship to modern paintings. The interplay between text and image, a common feature of lithographic printmaking that had no equivalent in painting, is one of the most intriguing aspects of Le Vocabulaire des dames. The “vocabulary” invoked in the series title draws attention to the phrases that accompany each figure in captions located beneath them. These consist of banal fragments of dialogue such as C’est possible [It’s Possible], No. 2, and rhetorical questions such as Viendrez vous? [Are You Coming?], No. 5 (Fig. 9). These texts, like the portrait format of the images, distance the large lithographs from the commercial world of fashion illustration contrasting as they do so clearly with the commercial information and descriptions of clothing in the captions of contemporary fashion plates (see Fig. 2).25 The phrases in Le Vocabulaire des dames impute an idea or a situation to the figures that pulls them toward narrative. The series begins by introducing the viewer/reader to scenarios that are vague and indeterminate: Peut-être! [Perhaps], No. 1 (see Fig. 1); C’est possible [It’s Possible], No. 2; Pourquoi pas! [Why Not!], No. 3. The situations evoked are open-ended in their uncertainty, without being troubling, and many questions are posed.

Fig. 8. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 24, IL EST GENTIL! | HOW AMIABLE HE IS!

It is instead the manner of dressing that realizes the prints’ claim to the individualization of portraiture. One elegant costume and striking coiffure follows another through twenty-four plates, each different from the other. This parade of outfits fulfilled the “fantasy” of dressing up promised by these “portraits de fantaisie.” Costume had always been the primary vehicle of fantasy in “portraits de fantaisie,” a genre of painting that included seventeenth-century Dutch tronies and Italian teste capriciosi through eighteenth-century English fancy pictures and Jean Honoré Fragonard’s famous series of some fifteen “portraits de fantaisie” (c.1769).20 These precedents exploited the transformative potential of costume, its ability to change people’s identities by dressing them in regional, foreign, or historical garb. Le Vocabulaire des dames, by contrast, muted that potential for the extraordinary by bringing the clothing portrayed into line with contemporary fashion: the outfits shown range from normative cosmopolitan to mildly exotic and historical, nothing too outlandish. The overwhelming majority are respectable daydresses, such as the brown pelerines, or dresses with matching capes, depicted in plates 8 and 16 (Figs. 6 and 18), which closely correspond to the one worn by Aline Chassériau in her brother Théodore’s 1835 portrait of her (Fig. 7). A few outfits incorporate more whimsical historical and exotic elements such as the jaunty seventeenth-century-style hat and fur-trimmed vest shown in Vocabulaire plate 24 (Fig. 8), and that blending of exotic motifs into the dominant contemporary silhouette was typical of the fashion and costume subjects depicted in prints of the 1830s.

In Hersent’s Portrait of Madame Arachequesne, by contrast, the sitter’s facial expression is emphasized at the expense of the clothing. One would expect this in an oil portrait though not to the degree of animation exhibited by Madame Arachequesne. Unlike most portrait sitters, who look solemnly out at the viewer with a studied lack of expression, Madame Arachequesne turns her head to one side and looks up, her lips slightly parted. This kind of angled upward glance was typically reserved for writers and musicians since it signified inspiration or rapt attention; Hersent himself had used it in his earlier portraits of the poet Delphine Gay and the writer Sophie Gay (both, 1824, Musée national du château, Versailles). In the absence of information about Madame Arachequesne, we can only observe that her expression lends her features an unusually emotive, genre-like character.21 Facial expressions of this kind, though unusual in oil portraits, were common in lithographs of imaginary subjects such as plate 10 from Le Vocabulaire des dames (see Fig. 4), in which a woman tilts her head and looks up and out of the frame. These prints would have helped legitimate and popularize emotive and sentimental expressions for adoption in fine art portraits.

In contrast to the rich variety of clothing styles, colors, fabrics, and trimmings shown in Le Vocabulaire des dames, Madame Arachequesne wears a simple white dress. This choice harkened back to the monochrome neo-Greek dresses of earlier decades and conformed to an unwritten law of painting that clothing should not detract from the face. Madame Arachequesne’s white dress, while elegant and up-to-date in its styling, was a conservative choice in pictorial terms. The main concessions the portrait made to fashionability are the sitter’s wide-brimmed straw hat decorated with red poppies and a wide belt that accentuates her slim waist. Neoclassical fashion had so valorized the undressed head that it remained unusual in the 1820s for women to wear hats in oil portraits, as the Portrait of Aline Chasseriau demonstrates (see Fig. 7), despite their revival in sartorial practice. Printed images, on the other hand, featured elaborate hats (see Fig. 2). Hersent’s painting resembles Grévedon’s lithographs as well as periodical fashion plates in making the hat into its crowning glory. In the interests of expressive effect both the painting and the lithograph frame women’s faces with lavishly decorated hats, though the balance between the latter is different in each case. Madame Arachequesne’s large animated face dominates her pale figure and is accentuated by the eye-catching red poppies on her hat and transparent red shawl draped over her lower arms. In the lithograph, however, visual attention is divided between the woman’s feathered beribboned hat, which frames a small head, and her colored dress with its scalloped bertha, crossed bodice and white layered sleeves. The clothing and coiffure are more vibrantly rendered than her body, which accords a higher priority to inanimate over human subjects.

While common ground was shared by lithographic “portraits de fantaisie” and oil portraits in the 1830s, we attend to these works quite differently. Modern oil paintings presume a singularity of execution and sustained viewing attention whereas these lithographs were designed for rapid consideration. When bound into an album, the sequencing of the prints creates a momentum that carries the viewer forward. Their vignette format, floating on the page with ragged, unbounded edges that blend into the sheet, leads one on to the next page. Many of the captions invoke the comings and goings of a potential encounter — Viendrez Vous? [Are You Coming?], No. 5; or A bientôt. | I’ll See You Very Soon, No. 19 – as if commenting on the viewer’s transitory engagement with the figures pictured. This is very different from the momentum of narrative, which directs a reader toward a goal. Here, the viewer’s relationship to the images is casual and undirected; one can take them or leave them, linger over one or move on to another. If a lithograph was extracted from a set, it could easily become part of another context such as a décor, and it has been argued that captions gave prints a self-contained independence as wall images.22

Oil paintings demanded a different kind of visual attention. Much larger than Grévedon’s lithograph, Hersent executed his Portrait of Madame Archequesne as a pendant to Portrait of Monsieur Arachequesne, which the artist’s wife, Louise Marie Jeanne Hersent (née Maudit) had completed the year before (1830; Paris, Musée Carnavalet). Despite matching the existing half of a pair, Hersent treated the composition of his portrait separately from that of its mate.23 The poses of husband and wife only vaguely mirror each other, and Madame Archequesne’s sideways glance flies over her husband’s head and misses him entirely. Hersent also introduced a foliage background behind his sitter, which creates a different sense of space and texture from the plain ground in the pendant portrait. The foliage fills out the frame and slows viewing down: one attends to distinctions in facture between the brushily painted greenery and the smoothly painted dress and to subtle differentiations of hue such as the buttery yellow sash set off from the white dress. Hersent exhibited this portrait at the Salon of 1831, which suggests that such distinctions of facture, texture, and color were meant to be noticed and appreciated.24 In contrast, the Grévedon series was sold commercially, by subscription and through shops in Paris and London, and not exhibited at the Salon, even though other types of lithographs at the time were.

Images and Texts

Texts had been integral to printed images since engraving began in the sixteenth century though only rarely were they brought into a direct physical and conceptual relationship to modern paintings. The interplay between text and image, a common feature of lithographic printmaking that had no equivalent in painting, is one of the most intriguing aspects of Le Vocabulaire des dames. The “vocabulary” invoked in the series title draws attention to the phrases that accompany each figure in captions located beneath them. These consist of banal fragments of dialogue such as C’est possible [It’s Possible], No. 2, and rhetorical questions such as Viendrez vous? [Are You Coming?], No. 5 (Fig. 9). These texts, like the portrait format of the images, distance the large lithographs from the commercial world of fashion illustration contrasting as they do so clearly with the commercial information and descriptions of clothing in the captions of contemporary fashion plates (see Fig. 2).25 The phrases in Le Vocabulaire des dames impute an idea or a situation to the figures that pulls them toward narrative. The series begins by introducing the viewer/reader to scenarios that are vague and indeterminate: Peut-être! [Perhaps], No. 1 (see Fig. 1); C’est possible [It’s Possible], No. 2; Pourquoi pas! [Why Not!], No. 3. The situations evoked are open-ended in their uncertainty, without being troubling, and many questions are posed.

![Fig. 9. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, 1831-34, No. 5, Viendrez vous? | [Are you coming?].](https://nonsite.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/9-Grevedon-Vocabulaire-des-Dames-1832-no-5-Viendrez-Vous-Clark-TIFF-373x600.jpg) Fig. 9. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, 1831-34, No. 5, Viendrez vous? | [Are you coming?].

Fig. 9. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, 1831-34, No. 5, Viendrez vous? | [Are you coming?]. Fig. 10. Achille Devéria, L’Attente, from Album lithographique de divers sujets composés et dessinés sur pierre par Devéria, pl. 11, Paris : Motte, 1829, lithograph in black on wove paper, in.-fol. (Departement des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris). Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Fig. 10. Achille Devéria, L’Attente, from Album lithographique de divers sujets composés et dessinés sur pierre par Devéria, pl. 11, Paris : Motte, 1829, lithograph in black on wove paper, in.-fol. (Departement des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris). Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.![Fig. 11. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 6, J’attends | [I wait].](https://nonsite.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/11-Grevedon-Vocabulaire-des-Dames-1832-no-6-J-attends-Clark-TIFF-375x600.jpg) Fig. 11. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 6, J’attends | [I wait].

About a third of the phrases are voiced in the first person and their placement immediately beneath the figures inclines one to impute them to the women depicted, who are then imagined as speaking or thinking subjects. The demi-dialogic form of the captions interpolates the viewer into the visual world of the print. This subjectivization of the viewing experience can be gauged by comparison with Achille Devéria’s L’Attente, 1829 (Fig. 10). Its caption assumes the passive voice of a disembodied narrator who describes “waiting” as the state of a woman shown standing outside. Le Vocabulaire des dames articulates the same idea in the first person – J’attends [I Wait], No. 6 (Fig. 11) – and the half-length “portrait” format pulls the viewer in close. The sense of being addressed by a speaking subject breaks down the objectivity of a viewer’s relationship to the figure depicted and establishes a fictional relationship of intimacy with it. However, the source of the utterance is often very unclear. A handful of phrases are voiced in the second person and could be uttered by someone outside the image: Viendrez Vous? [Will you come?], No. 5 (see Fig. 9) could be exclaimed by a viewer in response to this image rather than by the depicted figure. More than a third of the captions lack pronoun subjects and create considerable uncertainty about whether the utterance is coming within the image or is a commentary upon it: Peut-Être [Perhaps], No. 1 (see Fig. 1); A Demain. | To Morrow, No. 15.

The style of the phrases was relatively new and appears to belong to lithography as a medium. The captions are very short; the phrases are banal; and they do not comment diegetically on the image. The quippy exchanges attached to Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet’s vast corpus of military episodes and to Honoré Daumier’s newspaper caricatures exemplify the new trend in lithographic captions; however, those are proper dialogues, not the “half-a-logues” or rhetorical questions posed in Le Vocabulaire des dames. No caption in the Grévedon series is more than four words, some are only one (Perfide. | Perfidious, No. 21). These verbal fragments are not anchored to the image through a narrative or a commentary on it, unlike the rhymed quatrains that had for centuries been attached to prints, and told mini-stories about them, or the snatches of modern dialogue found in Charlet’s and Daumier’s lithographs. Crucially, nothing in the captions of Le Vocabulaire des dames refers specifically to the images nor, conversely, do the images depict a specific action or situation that calls for explanation. This radically opens up the semiotics of their address. It also releases the visual image from the grip of literature to be expressive on its own terms, considering William McAllister Johnson’s argument that in the eighteenth century, engraved images, particularly ones that appeared to lack a subject, were “commercially pointless without a text.”26

It is simply the physical proximity of the captions to the half-length figures that invites one to draw a connection between them. Yet that connection is a projection on the viewer’s part, as it was on the part of the editors Rittner and Goupil who probably composed the captions and appended them to the images supplied by Grévedon.27 Even when a statement made in the first-person seems to emanate from the figure above it, a disjunction or an uncertainty can intervene between the message and the image: nothing in the posture, expression or dress of No. 9 corresponds to “her” caption, Osez! | I Defy You (Fig. 12). Or again, the potential for sly humor in a caption such as “Peut-être” could be read as transforming the visual intent and undermining the primness of the sitter pictured in plate 1 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 11. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 6, J’attends | [I wait].

About a third of the phrases are voiced in the first person and their placement immediately beneath the figures inclines one to impute them to the women depicted, who are then imagined as speaking or thinking subjects. The demi-dialogic form of the captions interpolates the viewer into the visual world of the print. This subjectivization of the viewing experience can be gauged by comparison with Achille Devéria’s L’Attente, 1829 (Fig. 10). Its caption assumes the passive voice of a disembodied narrator who describes “waiting” as the state of a woman shown standing outside. Le Vocabulaire des dames articulates the same idea in the first person – J’attends [I Wait], No. 6 (Fig. 11) – and the half-length “portrait” format pulls the viewer in close. The sense of being addressed by a speaking subject breaks down the objectivity of a viewer’s relationship to the figure depicted and establishes a fictional relationship of intimacy with it. However, the source of the utterance is often very unclear. A handful of phrases are voiced in the second person and could be uttered by someone outside the image: Viendrez Vous? [Will you come?], No. 5 (see Fig. 9) could be exclaimed by a viewer in response to this image rather than by the depicted figure. More than a third of the captions lack pronoun subjects and create considerable uncertainty about whether the utterance is coming within the image or is a commentary upon it: Peut-Être [Perhaps], No. 1 (see Fig. 1); A Demain. | To Morrow, No. 15.

The style of the phrases was relatively new and appears to belong to lithography as a medium. The captions are very short; the phrases are banal; and they do not comment diegetically on the image. The quippy exchanges attached to Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet’s vast corpus of military episodes and to Honoré Daumier’s newspaper caricatures exemplify the new trend in lithographic captions; however, those are proper dialogues, not the “half-a-logues” or rhetorical questions posed in Le Vocabulaire des dames. No caption in the Grévedon series is more than four words, some are only one (Perfide. | Perfidious, No. 21). These verbal fragments are not anchored to the image through a narrative or a commentary on it, unlike the rhymed quatrains that had for centuries been attached to prints, and told mini-stories about them, or the snatches of modern dialogue found in Charlet’s and Daumier’s lithographs. Crucially, nothing in the captions of Le Vocabulaire des dames refers specifically to the images nor, conversely, do the images depict a specific action or situation that calls for explanation. This radically opens up the semiotics of their address. It also releases the visual image from the grip of literature to be expressive on its own terms, considering William McAllister Johnson’s argument that in the eighteenth century, engraved images, particularly ones that appeared to lack a subject, were “commercially pointless without a text.”26

It is simply the physical proximity of the captions to the half-length figures that invites one to draw a connection between them. Yet that connection is a projection on the viewer’s part, as it was on the part of the editors Rittner and Goupil who probably composed the captions and appended them to the images supplied by Grévedon.27 Even when a statement made in the first-person seems to emanate from the figure above it, a disjunction or an uncertainty can intervene between the message and the image: nothing in the posture, expression or dress of No. 9 corresponds to “her” caption, Osez! | I Defy You (Fig. 12). Or again, the potential for sly humor in a caption such as “Peut-être” could be read as transforming the visual intent and undermining the primness of the sitter pictured in plate 1 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 12. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 9, Osez! | I Defy You.

Fig. 12. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 9, Osez! | I Defy You. Fig. 13. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 19, A Bientot | I’ll See You Very Soon.

Fig. 13. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 19, A Bientot | I’ll See You Very Soon. Fig. 14. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 13, Passez Vot’ chemin. | Go Your Way.

Fig. 14. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 13, Passez Vot’ chemin. | Go Your Way. Fig. 15. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 14, Irai-Je? | Shall I Go.

Fig. 15. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des Dames, No. 14, Irai-Je? | Shall I Go. Fig. 16. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 23, Venez-Vous. | Will You Come.

The relation of captioned phrases to images is so loose as to sometimes seem arbitrary. What is there about the figures portrayed in plates 8 and 19 (see Fig. 6 and Fig. 13) that corresponds to the captions, Je ne Veux Pas | I Will Not, in the first instance, and A Bientot | I’ll See You Very Soon, in the second? The distinctions come down to subtle differences in pose and costuming, and this is where the costuming comes in as conveying moral and social connotations that help constitute, and mix, the “message” of the printed image. The woman depicted in No. 13, Passez Vot’ chemin. | Go Your Way, appears to reject the prospect of company by turning her back on us; she wears a wide-brimmed hat set at a determined angle (Fig. 14). The next print in the sequence, No. 14, suggests the opposite attitude, receptivity toward an encounter, by facing us with wide eyes and seeming to pose a question that we readily ascribe to her: Irai-Je? | Shall I Go (Fig. 15). One effect of the minimalized body language of and absence of setting for these figures is to shift expressive power to the attire. Nos. 13 and 14 are both dressed like Swiss exotics yet the low-cut chemise, split-front bodice, and flower-strewn hat of No. 14 are more inviting than the covered-up, angular costume of her counterpart No. 13. Costume helps create the affective sense of each figure. To put this another way, pose alone is not enough to indicate a “narrative” situation or an emotional state. One back-turned female, No. 23 (Fig. 16), is accompanied by a caption, Venez-Vous. | Will You Come., that conveys almost the opposite message to that of Passez Vot’ chemin. | Go Your Way, under a similarly posed figure, No. 13 (see Fig. 14).

Typography plays its part in keeping the options of viewer engagement open. The design of the captions contributes to their lack of “narrative” anchoring. Rather than being contained within a box or by a frame, which establishes a separate but linked relation to an image, the captions float on the sheets beneath the images. They blend into the white space, like the unbounded vignettes themselves. Printed in block capital letters, the formality of the typography detaches the captions from the depicted figures. The capital letters suggest an emphatic and declarative tone, which is reinforced by periods as the preferred form of punctuation, with question marks often omitted from interrogative sentences. These traits make the phrases more difficult to read as articulated speech than the mixture of upper and lower case characters and sprinkling of punctuation marks in the captions on Charlet’s and Daumier’s lithographs. If the typography of Le Vocabulaire des Dames removes it from the syntax of spoken language, the open form of the letters’ design seems to allow sound to pass through them. Anyone could be speaking.

The interplay between the caption texts and the images in Le Vocabulaire des dames might be related to Roland Barthes’s discussion of the “relay” function of a linguistic message with regard to an iconic message in his analysis of an advertisement in “Rhetoric of the Image” (1964; trans. 1977): “Here text (most often a snatch of dialogue) and image stand in a complementary relationship.”28 The “snatches” of dialogue in the captions of Le Vocabulaire des dames do not describe the women pictured or the garments they wear; rather the captions “relay” messages to the images that come from the outside world. Since the image is as fragmentary as the text, “the unity of the message [of the iconic whole],” Barthes continued,” is realized at a higher level, that of the story, the anecdote, the diegesis.”29 He had in mind the comic strip and the film, iconic forms that have a narrative, diegetic impulse built into their sequencing of images. Le Vocabulaire des dames takes serial form, too, but its images are repetitive and its caption texts do not advance the action of a story or plot. How can we understand “story” or “anecdote” to be operating in these prints? Where do their extra-iconic messages come from?

Barthes’s analysis of the “rhetoric of Fashion” from The Fashion System (1967; trans. 1983) is useful in this regard. Referring to the “law of Fashion euphoria,” which forbids reference to anything aesthetically or morally displeasing, he observed:

Fig. 16. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 23, Venez-Vous. | Will You Come.

The relation of captioned phrases to images is so loose as to sometimes seem arbitrary. What is there about the figures portrayed in plates 8 and 19 (see Fig. 6 and Fig. 13) that corresponds to the captions, Je ne Veux Pas | I Will Not, in the first instance, and A Bientot | I’ll See You Very Soon, in the second? The distinctions come down to subtle differences in pose and costuming, and this is where the costuming comes in as conveying moral and social connotations that help constitute, and mix, the “message” of the printed image. The woman depicted in No. 13, Passez Vot’ chemin. | Go Your Way, appears to reject the prospect of company by turning her back on us; she wears a wide-brimmed hat set at a determined angle (Fig. 14). The next print in the sequence, No. 14, suggests the opposite attitude, receptivity toward an encounter, by facing us with wide eyes and seeming to pose a question that we readily ascribe to her: Irai-Je? | Shall I Go (Fig. 15). One effect of the minimalized body language of and absence of setting for these figures is to shift expressive power to the attire. Nos. 13 and 14 are both dressed like Swiss exotics yet the low-cut chemise, split-front bodice, and flower-strewn hat of No. 14 are more inviting than the covered-up, angular costume of her counterpart No. 13. Costume helps create the affective sense of each figure. To put this another way, pose alone is not enough to indicate a “narrative” situation or an emotional state. One back-turned female, No. 23 (Fig. 16), is accompanied by a caption, Venez-Vous. | Will You Come., that conveys almost the opposite message to that of Passez Vot’ chemin. | Go Your Way, under a similarly posed figure, No. 13 (see Fig. 14).

Typography plays its part in keeping the options of viewer engagement open. The design of the captions contributes to their lack of “narrative” anchoring. Rather than being contained within a box or by a frame, which establishes a separate but linked relation to an image, the captions float on the sheets beneath the images. They blend into the white space, like the unbounded vignettes themselves. Printed in block capital letters, the formality of the typography detaches the captions from the depicted figures. The capital letters suggest an emphatic and declarative tone, which is reinforced by periods as the preferred form of punctuation, with question marks often omitted from interrogative sentences. These traits make the phrases more difficult to read as articulated speech than the mixture of upper and lower case characters and sprinkling of punctuation marks in the captions on Charlet’s and Daumier’s lithographs. If the typography of Le Vocabulaire des Dames removes it from the syntax of spoken language, the open form of the letters’ design seems to allow sound to pass through them. Anyone could be speaking.

The interplay between the caption texts and the images in Le Vocabulaire des dames might be related to Roland Barthes’s discussion of the “relay” function of a linguistic message with regard to an iconic message in his analysis of an advertisement in “Rhetoric of the Image” (1964; trans. 1977): “Here text (most often a snatch of dialogue) and image stand in a complementary relationship.”28 The “snatches” of dialogue in the captions of Le Vocabulaire des dames do not describe the women pictured or the garments they wear; rather the captions “relay” messages to the images that come from the outside world. Since the image is as fragmentary as the text, “the unity of the message [of the iconic whole],” Barthes continued,” is realized at a higher level, that of the story, the anecdote, the diegesis.”29 He had in mind the comic strip and the film, iconic forms that have a narrative, diegetic impulse built into their sequencing of images. Le Vocabulaire des dames takes serial form, too, but its images are repetitive and its caption texts do not advance the action of a story or plot. How can we understand “story” or “anecdote” to be operating in these prints? Where do their extra-iconic messages come from?

Barthes’s analysis of the “rhetoric of Fashion” from The Fashion System (1967; trans. 1983) is useful in this regard. Referring to the “law of Fashion euphoria,” which forbids reference to anything aesthetically or morally displeasing, he observed:

The resistance to pathos is all the more notable here in that Fashion rhetoric . . . tends increasingly to the novelistic; and if it is possible to conceive and to enumerate novels “in which nothing happens,” literature does not offer a single example of a continually euphoric novel; perhaps Fashion wins this wager insofar as its narrative is fragmentary, limited to citations of decor, situation, and character, and deprived of what could be called organic maturation of the anecdote; in short, Fashion would derive its euphoria from the fact that it produces a rudimentary, formless novel without temporality: time is not present in the rhetoric of Fashion.30The relay between texts and images in Le Vocabulaire des dames alludes to a series of potential encounters which express a wish, a doubt, a possibility, and which are never negative or judgmental. The texts refuse to impose a moral judgment on the images, which was one of the primary functions that texts had performed in late seventeenth and eighteenth century prints. The captions consequently avoid categorizing the images. The vague incidents they evoke are left open to interpretation in an eternal present. They are not trying to tell us anything so much as trying simply to increase the evocativeness or immediate affectivity of the prints. The question of audience The strategy of interpolation suggested by the demi-dialogic captions in these lithographs was not new and lay at the origins of French fashion prints from the last quarter of the seventeenth century.31 The questions for the early nineteenth-century series are, who was the implied audience for these large lithographs? What was their probable social function? These questions cannot be answered with any certainty for lack of documentary evidence, as Beatrice Farwell observed in her 1980s survey of popular lithography:

Pictures such as these, inexpensive and ephemeral, raise the inevitable questions—who bought them, how were they used, and in what quantities were they produced. Most of these questions are unanswerable with any certainty, owing to the lack of documentary evidence on the interface between a copious commercial production and its social destination.32Precisely because so little in the way of concrete information is known about the contemporary consumption and production of the prints, they are hostage to the preoccupations and ideological concerns of scholars who interpret them and their reception.33 Thus for Farwell, feminist paradigms of the 1970s and ‘80s underpinned her classification of images of women, “largely passive feminine types,” under the category “Pinups and Erotica” rather than, for example, in her volume on “Portraits and Types.” Even though she recognized that in the former category “the range in degree of sexual suggestiveness or explicitness is considerable,” and that many of the prints included in it “are innocent enough to have been framed and hung in decorative groups in the most proper bourgeois home,” she nevertheless stressed their eroticism, sexism and presumed male audience.34 She emphasized “gallant subjects (sujets galans),” “oriented more or less exclusively for the pleasure of the male consumer,” and argued that they were intended for “the bachelor market,” seconded by “prostitutes and demi-mondaines [who] formed a female counterpart to the legions of unmarried men.” These libertine subjects are not far removed in her interpretation from “Gracious subjects (Sujets gracieux),” which included Grévedon’s series, as “a euphemism for sexually suggestive or erotic subjects”: “Pretty women both French and foreign speak of the universal appeal of youth and beauty, a sort of ecumenical eroticism in varied costumes but sharing a similar address to the (male) viewer.”35 Some prints in the Grévedon series certainly sustain such an interpretation but all of them do not. The presumption of a male auditor for the indeterminate caption Bonjour! | Good Morning, No. 7, seems clarified by the image, which, exceptionally for the series, represents a woman wearing negligée in bed (Fig. 17). The wide-eyed looks and passive receptivity of other figures suggests coy flirtation, born out by a caption such as Vous me flattez. | You Flatter Me, No. 18. Yet the series’ emphasis on the stylings of women’s clothes does not seem exclusively or even primarily oriented to a male audience, and Farwell’s explanation of the up-to-date costumes and coiffures, as signs of modernity and realism that separated “popular or vulgar imagery” from “the iconography of high art, at least until the 1860s,” seems inadequate to the variety and detail of the outfits portrayed and fails to acknowledge any cross-over between lithographic and fine art production that already takes place in the 1830s.36 If there is an erotic appeal in Le Vocabulaire des dames, it is an eroticism of the material, not of the sexual.

Fig. 17. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 7, Bonjour! | Good Morning.

Fig. 17. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 7, Bonjour! | Good Morning. Fig. 18. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 16, Je l’oublierai. | I Will Forget Him.

Fig. 18. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 16, Je l’oublierai. | I Will Forget Him. Fig. 19. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 12, Je suis engagée. | I Am Engaged.

The semiotic indeterminacy of the prints—of their captions and the vague situations evoked—is even more significant in qualifying (heterosexual) eroticism as their primary valence. Several lithographs hedge their bets on the gendering of the audience through remarks made in the captions about men: Je l’oublierai. | I Will Forget Him, No. 16 (Fig. 18); Pauvre jeune homme! | Poor Young Man!, No. 17; and Il est gentil! | How Amiable He Is!, No. 24, are statements that appear to be uttered by a woman or confided to a female friend. In fact, the majority of phrases are gender-neutral and depend upon context for their sense. If uttered by the woman depicted, Je suis engagée. | I Am Engaged, No. 12 (Fig. 19) could imply a rebuff of a male suitor but if this statement were made to a female friend, it would become a confidence or, if addressed to mixed company, it might have the declarative tone of an announcement, and the image itself would support all three interpretations. This fashion print series seem more or less opportunistically titled to allow for whatever associations a viewer wishes to make, only sometimes being explicitly content driven.

Given the lack of direct documentary evidence regarding their consumption, quite different interpretations of reception could be projected for these prints, depending again upon an interpreter’s predilections. Women could be constructed as the primary audience for the prints, a reading which would not necessarily remove their functioning in the straightforwardly sexist way that Farwell critiqued but would re-direct it toward female consumers and viewers as pupils to be schooled or socially educated by such imagery. Such interpretations depends upon a presumed homology between image and audience, on deducing a female audience from the female subjects depicted in the prints. It could be extended from gender to social class, whereby images of bourgeois women would be directed at bourgeois women and girls. To try and typify the consumption of the images in such a way however assumes a rather monolithic relationship between the image and the gender and class, as well as belief systems and social attitudes, of the supposed audience. In this case, for one thing, it would leave aside the fascination that visualizing and writing about female fashion evidently exercised on male authors and writers, the most striking example being Stéphane Mallarmé, who invented highly sensuous and specific descriptions of the cut, colors, trimmings, and fabrics of women’s dresses for a set of fashion plates that never existed in his journal La Dernière mode (1874).37

The idea that such work was designed at least in part to appeal to a female audience though does have considerable grounds for plausibility. Most of what we know about the consumption of fashion as a subject is based on periodical literature; and in her publication history of the long-running Journal des dames et des modes (1797-1839), Annemarie Kleinert argued on the basis of internal evidence that the journal addressed itself largely to middle-class women between the ages of eighteen and forty. She documented its subscription base as between 1,000 and 2,500, with a readership many times greater, reaching as many as 11,000 people; most of the thirty fashion journals published in the 1830s had a comparable subscription base (between 1,000 and 2,000).38 Citing studies of reading room publics, she emphasized the social range of readers who frequented them, and could rent the journal for as little as five centimes a day, as encompassing “seamstresses, lower middle class women, actresses out of work, luxurious courtesans, false ‘devotes,’ the farmer from the region and even the cook.”39

The middle-class and aristocratic women who could have afforded to subscribe to a fashion journal overlapped with the audience intended for “keepsake” books, also called “commonplace” books, which were luxury objects that contained a selection of printed images and texts or blank pages.40 The variety of pictorial genres featured in keepsakes (narrative scenes, landscapes, portraits) included half-length portraits of aristocratic British women (belying the British origin of keepsakes), famous women of the past, and imaginary female figures, which resemble the general figure type depicted by Grévedon and others.41 However, the volumes served a different purpose: keepsakes were proscriptive in educating women in proper middle-class codes of behaviour and deportment and reinforced domestic values whereas large lithographs such as Le Vocabulaire des dames were much more open in their semiotic codes of address. The lithographic series and keepsake portrait images thus appear as discreet and nearly contemporaneous responses to the popularity and imaginative potential of the half-length portrait format.42

The social education promulgated by keepsake books tends to deprive their female recipients of much agency; they are objectified and manipulated much as they are by the eroticization in “pretty women” imagery. Prints such as Grévedon’s, however, are not readily subsumed within such a paradigm. They really need to be placed in the context of the remarkable development of textual and popular commercial culture during the July Monarchy, particularly the culture of fashion. As Hazel Hahn has noted in her study of the commercial fashion culture of the period, “it was shopping as a pleasurable activity, and dress as an expression of one’s taste, that dominated the magazines,” rather than “the ideas of making the home beautiful and comfortable or aimed at fulfilling the duties of a housewife.”43 This edged out an earlier Enlightenment theme in fashion journals that maternity and fashionability were perfectly compatible states and aspirations. While the theme of “taste” had emerged in cultural journals in the wake of the French Revolution, as a democratic leveller that could be taught to and acquired by aspirant social groups, the 1830s saw an expansion of the idea that good “taste” was the key to customizing one’s appearance within the parameters of the dominant style.44 A “new modern idea of fashion as an individual interpretation of a trend” emerged in the July Monarchy,” and Honoré de Balzac gave the concept literary form in Ferragus (1835) when he described the troubles his character Madame Jules took to decorate her house and dress her person:

Fig. 19. Henri Grévedon, Le Vocabulaire des dames, No. 12, Je suis engagée. | I Am Engaged.

The semiotic indeterminacy of the prints—of their captions and the vague situations evoked—is even more significant in qualifying (heterosexual) eroticism as their primary valence. Several lithographs hedge their bets on the gendering of the audience through remarks made in the captions about men: Je l’oublierai. | I Will Forget Him, No. 16 (Fig. 18); Pauvre jeune homme! | Poor Young Man!, No. 17; and Il est gentil! | How Amiable He Is!, No. 24, are statements that appear to be uttered by a woman or confided to a female friend. In fact, the majority of phrases are gender-neutral and depend upon context for their sense. If uttered by the woman depicted, Je suis engagée. | I Am Engaged, No. 12 (Fig. 19) could imply a rebuff of a male suitor but if this statement were made to a female friend, it would become a confidence or, if addressed to mixed company, it might have the declarative tone of an announcement, and the image itself would support all three interpretations. This fashion print series seem more or less opportunistically titled to allow for whatever associations a viewer wishes to make, only sometimes being explicitly content driven.

Given the lack of direct documentary evidence regarding their consumption, quite different interpretations of reception could be projected for these prints, depending again upon an interpreter’s predilections. Women could be constructed as the primary audience for the prints, a reading which would not necessarily remove their functioning in the straightforwardly sexist way that Farwell critiqued but would re-direct it toward female consumers and viewers as pupils to be schooled or socially educated by such imagery. Such interpretations depends upon a presumed homology between image and audience, on deducing a female audience from the female subjects depicted in the prints. It could be extended from gender to social class, whereby images of bourgeois women would be directed at bourgeois women and girls. To try and typify the consumption of the images in such a way however assumes a rather monolithic relationship between the image and the gender and class, as well as belief systems and social attitudes, of the supposed audience. In this case, for one thing, it would leave aside the fascination that visualizing and writing about female fashion evidently exercised on male authors and writers, the most striking example being Stéphane Mallarmé, who invented highly sensuous and specific descriptions of the cut, colors, trimmings, and fabrics of women’s dresses for a set of fashion plates that never existed in his journal La Dernière mode (1874).37

The idea that such work was designed at least in part to appeal to a female audience though does have considerable grounds for plausibility. Most of what we know about the consumption of fashion as a subject is based on periodical literature; and in her publication history of the long-running Journal des dames et des modes (1797-1839), Annemarie Kleinert argued on the basis of internal evidence that the journal addressed itself largely to middle-class women between the ages of eighteen and forty. She documented its subscription base as between 1,000 and 2,500, with a readership many times greater, reaching as many as 11,000 people; most of the thirty fashion journals published in the 1830s had a comparable subscription base (between 1,000 and 2,000).38 Citing studies of reading room publics, she emphasized the social range of readers who frequented them, and could rent the journal for as little as five centimes a day, as encompassing “seamstresses, lower middle class women, actresses out of work, luxurious courtesans, false ‘devotes,’ the farmer from the region and even the cook.”39

The middle-class and aristocratic women who could have afforded to subscribe to a fashion journal overlapped with the audience intended for “keepsake” books, also called “commonplace” books, which were luxury objects that contained a selection of printed images and texts or blank pages.40 The variety of pictorial genres featured in keepsakes (narrative scenes, landscapes, portraits) included half-length portraits of aristocratic British women (belying the British origin of keepsakes), famous women of the past, and imaginary female figures, which resemble the general figure type depicted by Grévedon and others.41 However, the volumes served a different purpose: keepsakes were proscriptive in educating women in proper middle-class codes of behaviour and deportment and reinforced domestic values whereas large lithographs such as Le Vocabulaire des dames were much more open in their semiotic codes of address. The lithographic series and keepsake portrait images thus appear as discreet and nearly contemporaneous responses to the popularity and imaginative potential of the half-length portrait format.42

The social education promulgated by keepsake books tends to deprive their female recipients of much agency; they are objectified and manipulated much as they are by the eroticization in “pretty women” imagery. Prints such as Grévedon’s, however, are not readily subsumed within such a paradigm. They really need to be placed in the context of the remarkable development of textual and popular commercial culture during the July Monarchy, particularly the culture of fashion. As Hazel Hahn has noted in her study of the commercial fashion culture of the period, “it was shopping as a pleasurable activity, and dress as an expression of one’s taste, that dominated the magazines,” rather than “the ideas of making the home beautiful and comfortable or aimed at fulfilling the duties of a housewife.”43 This edged out an earlier Enlightenment theme in fashion journals that maternity and fashionability were perfectly compatible states and aspirations. While the theme of “taste” had emerged in cultural journals in the wake of the French Revolution, as a democratic leveller that could be taught to and acquired by aspirant social groups, the 1830s saw an expansion of the idea that good “taste” was the key to customizing one’s appearance within the parameters of the dominant style.44 A “new modern idea of fashion as an individual interpretation of a trend” emerged in the July Monarchy,” and Honoré de Balzac gave the concept literary form in Ferragus (1835) when he described the troubles his character Madame Jules took to decorate her house and dress her person:

Any woman of taste could do as much, even though the planning of these things requires a stamp of personality which gives originality and character to this or that ornament, to this or that detail. Today more than ever before, there reigns a fanatical craving for self-expression.45This idea of fashion as a means of expressing individuality complimented a “view of shopping as an activity of leisurely amusement or empowerment that increased women’s influence both at home and in retail and production.”46 Consumption was one of the few public activities in which women were encouraged to engage, and they became the target audience both for print culture and fashion culture.47 This was not an inconsiderable audience to address since there is some indication that French women controlled the family budget in the nineteenth century.48 The tasteful individualization of appearance seems compatible with the emphasis on contemporary French fashion in the Le Vocabulaire des dames. The term “vocabulary” in the series title had a visual as well as a verbal dimension. It can be taken to refer to a style of dressing rather than to a collection of garments, considering that the items of clothing shown are not fully rendered, named or described as they are in contemporary fashion journals. From the lithographs one learns about combinations of elements that create a certain look. Plate 5 indicates that a floral print dress with spikey vandyked sleeves is balanced by rounded loops of hair and a monochrome butterfly bow projecting off the head (see Fig. 9). Plate 9 suggests that a solid green dress set offs accessories such as a thick chain necklace and dark fur boa and that hair rolls and an Aphrodite knot echo their curved forms (see Fig. 12). In so far as Le Vocabulaire des dames functions as a visual primer of style, it refers to acts of dressing (in linguistic terms, to speech acts, la parole) more than it does to a collection of garments (to language as a reservoir of words, la langue) from which an individual might compose a look.49 One context for understanding the subjectivization of viewing and address to the common culture in Le Vocabulaire des dames is provided by the correspondence section of the fashion press, which employed “half-a-logues” similar to those in the prints to entice and represent public participation.50 The editors of the New Monthly Belle Assemblée published replies to people who had submitted poems and essays for publication, responding on average to twenty-five a month in the 1840s.51 The editors identified their correspondents only by initials and replied to them in quite specific terms without filling the reader in on the first part of the correspondence. Half of a conversation was published, much as in Le Vocabulaire des dames one seems to eavesdrop on the middle of an exchange. It remains open to question whether the essays and poems discussed, or letters to the editor published in the correspondence section, were actually written by readers and subscribers rather than being invented by the editors.52 Whether fictional or actual, correspondence with readers highlights the allure that publically exposing “private” communications held for the reading public. The thrill and safety of this kind of exposure depended on the anonymity of the public sphere and the illusion of participation in it, which was created by suggesting that any reader’s query would be dignified by a response and that anyone with aspirations to write might see her or his work in print. This open form of demi-dialogic conversation was readily transposed to fashion-related lithographs such as Le Vocabulaire des dames given the material culture of clothing of the time: soliciting the participation of viewers of prints was important in an era before haute-couture and ready-to-wear, when individual consumers actively engaged in selecting the fabrics, trimmings, designs and accessories for their own clothes.53 Fashion “portraits” and the market in images Large-scale lithographic “portraits” of fashionable women proliferated in the late 1820s and 1830s. Henri Grévedon designed about twenty series between 1828 and 1840, each containing between four to twenty-eight prints. Achille Devéria was another artist who abandoned engraving for lithography and found the medium congenial for series of imaginary female figures; he was Grévedon’s major competitor in this genre. Jean Gigoux, Octave Tassaert, Léon Noël and Charles Philipon also made lithographs of this type, inventing designs and occasionally reproducing paintings by other artists. In the realm of fine art, the French painters who produced half-length “portraits” of imaginary costumed women included Joseph-Désiré Court, Édouard Dubufe, Charles Emile Callende de Champmartin, and Thomas Couture.

Fig. 20. Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of Miss Rosamond Crocker, later Lady Barrow, 1827, oil on canvas, 81.28 x 63.5 cm (32 x 25 in.) (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo). Photo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery/Art Resource, NY.

Fig. 20. Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of Miss Rosamond Crocker, later Lady Barrow, 1827, oil on canvas, 81.28 x 63.5 cm (32 x 25 in.) (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo). Photo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery/Art Resource, NY.  Fig. 21. Emilien Desmaisons, Je dois oublier | I must forget him, 1833, lithograph in black on wove paper, 32 x 27 cm (image), 41.5 x 31 cm (sheet) (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris).

But the most striking indication of the slide between painting and printmaking across this genre was the reinterpretation of portraits by the English painter Thomas Lawrence for the French print market. Lawrence burst onto the French scene with the exhibition of his works at the Salon of 1824, where he was awarded the cross of the Legion of Honor. His paintings, especially portraits of women and children, enjoyed popularity in France under the guise of genre subjects: the identities of his aristocratic English sitters were striped out of reproductive engravings and lithographs after his portraits and replaced with generic titles or captions. His Portrait of Miss Rosamond Crocker, later Lady Barrow, 1827 (Fig. 20), thus became Je dois oublier | I must forget him in a large lithograph by Emilien Desmaisons from 1833 (Fig. 21).54 The print belonged to a series of six “gracious subjects” by Desmaisons after Lawrence, which transformed portraits into generic female subjects: Une Grande Dame | A Lady, based on Lawrence’s Portrait of Mrs. Robert, later Lady Peel (1827, Frick Collection, New York); Une Jeune Mère | A Young Mother; Une Jeune Veuve | A Young Widow; La Jolie Villageoise ? A Cottage Girl (after Edwin Henry Landseer); and Pense-t-il a moi? | Is he thinking of me? These were yet another example of portraiture’s role as a vehicle for imaginative projection at the time. The craze for Lawrence-derived images of “pretty women” suggests that the figure type may have originated in England and been exported to France, either by means of direct transmission—Grévedon would have had ample opportunity to study Lawrence’s work in London and absorb the soft sentiment that suffused his portrayal of women—or by means of engravings—Samuel Cousins’s mezzotint Miss Crocker (1828, National Portrait Gallery, London) was probably the intermediary for Desmaisons’s Je dois oublier | I must forget him (see Fig. 21). The emphasis on variations in fashionable clothing in Grévedon’s (and others’) series would then represent a French contribution to the genre, at a time when Paris was advancing its cultural claim to inventiveness in fashion design. The demi-dialogic form taken by two of Desmaisons’s captions was probably influenced by the Grévedon series: Je dois oublier | I must forget him closely recalls the Vocabulaire’s Je l’oublierai. | I Will Forget Him, No. 16 (see Fig. 18). That is, the Lawrence/Desmaisons series of large lithographs thus extended the arbitrary nature of the captions’ relation to the images.

The market for prints after Lawrence in France is only one indication of the cultural traffic between London and Paris that flourished after 1815, especially after 1828 when French taxes on prints imported from England were lifted.55 The presence of bi-lingual captions in Le Vocabulaire des dames and in the Desmaisons series points to cooperation between print publishers that sustained international sales; in fact, the brevity of the captions may have been a practical solution to fitting two languages on one line. In a long-standing convention, publishers who financed the prints printed their names and addresses on them: Rittner and Goupil in Paris and Charles Tilt in London published Le Vocabulaire des dames while Jeannin in Paris and Bailly, Ward & Co. in New York published the Desmaisons series.56 French artists and publishers needed the English and American markets since the French exported more printed images than they imported.57 That balance sheet conditioned the reception of work by Lawrence in France as well as the cross-Channel marketing of Grévedon’s dreamy English-infused bilingual series of fashionable women. Lines of collaboration crossed and were multiple: the London merchant Tilt co-published with nearly every art house in Paris while an artist such as Grévedon was hired by eight different editors in Paris.58 In these decades before art publishing houses were large enough to establish branches in foreign cities (Goupil, Vibert & Co. first did so in 1846), individual prints and series were apparently commissioned by different houses on a subject-by-subject basis.59 There is precious little evidence of the contractual arrangements that must have existed between publishers in different cities; at the very least, letters of credit or a private account for exchanging cash would have been needed to facilitate international sales, arrangements that still depended upon first-hand knowledge and trust of a business partner.60

Fig. 21. Emilien Desmaisons, Je dois oublier | I must forget him, 1833, lithograph in black on wove paper, 32 x 27 cm (image), 41.5 x 31 cm (sheet) (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris).