Ex Machina’s premise offers a twenty-first-century take on a familiar sci-fi theme. A monomaniacal programmer, Nathan, does not pause his pursuit of creating artificial life to ask whether he should do so, nor does he ask what obligation he has to his creation once he has. Having made a robot he names Ava, Nathan manipulates an employee, Caleb, to spend a week in his isolated home laboratory to conduct a modified Turing test. The test is modified because, unlike the standard Turing evaluator, Caleb already knows Ava is a machine. The question he sets out to answer concerns whether the machine is simulating consciousness or actually is conscious.1 Typical for the genre this film develops, the plot takes a tragic turn because Nathan fails to consider the normative questions concerning his ethical obligations. Ex Machina, though, contributes to this sci-fi exploration (evident since at least Frankenstein) by reflecting on the nature of intentional action itself (increasingly pressing since the second half of the twentieth century). “Why did you make Ava?” Caleb asks, to which Nathan responds, “The arrival of strong artificial intelligence has been inevitable for decades. The variable was when, not if. So, I don’t really see her as a decision. Just an evolution.”2

Whereas G.E.M. Anscombe defines intentional actions as “those to which a certain sense of the question ‘Why?’ is given application,” Nathan “refus[es] application” of the question.3 Instead, he characterizes his non-decision as something like an event situated along an evolutionary causal chain. Nathan’s refusal is not simply an example of ethical abdication (although it is that too). Ex Machina explicitly connects Nathan’s attenuated account of agency to a deflationary account of the production of art by turning to Jackson Pollock’s 1948 painting, No. 5. Pointing to the painting, Nathan says to Caleb, “Pollock. The drip painter. He let his mind go blank and his hand go where it wanted. Not deliberate, not random. Some place in between. They called it automatic art.”4 Just as Nathan claims not to have made a decision tied to the question why, Pollock (on Nathan’s account) freed his mind of deliberation and simply let his hand go where it may.

Nathan apagogically reduces the Anscombean why question, seemingly demonstrating its irrelevance to the production of art. He asks Caleb to consider, “What if Pollock had reversed the challenge? Instead of trying to make art without thinking, he said: I can’t paint anything unless I know exactly why I’m doing it. What would have happened?”5 That is, had Pollock considered the why question, he would have been rendered immobile: “He never would have made a single mark.”6 The apparent practical irrelevance of this question suggests to Nathan that the act of dripping paint onto a canvas is “automatic” instead of deliberate. Indeed, to him, actions as such are more likely to be “automatic” than not. “The challenge,” he concludes, “is to find an action that is not automatic. From talking, to breathing, to painting. To fucking. To falling in love.”7

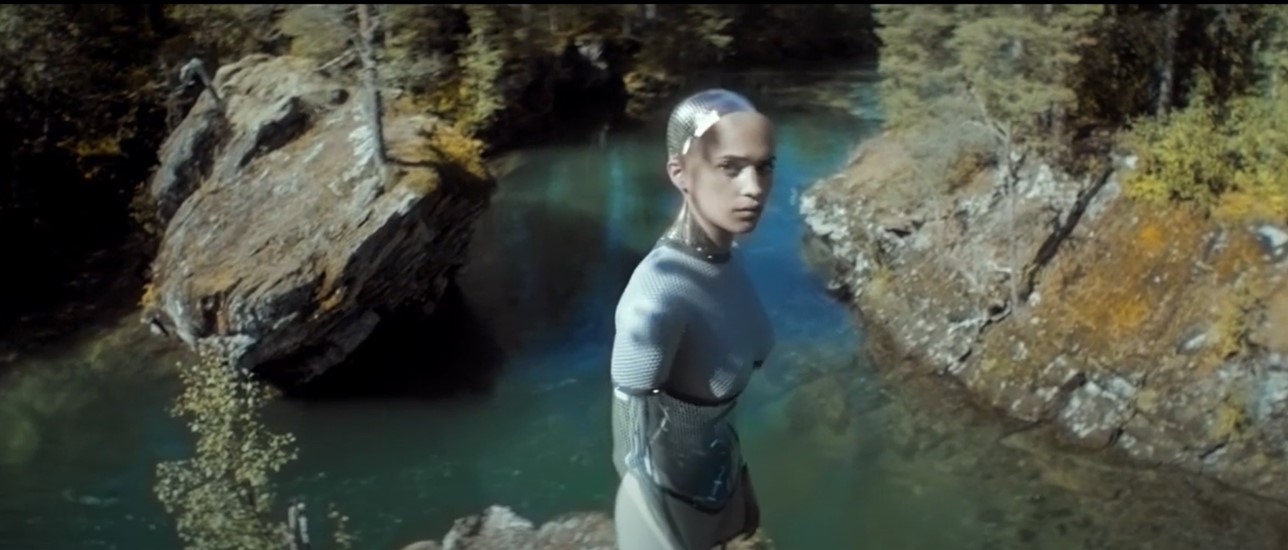

As I show in what follows, Nathan’s account (of his non-decision, of Pollock’s art) relates theories of action to accounts of art and does so by exacerbating the philosophical theories developed against Anscombe’s insights. Ex Machina pushes philosophers’ arguments to conclusions they would not accept as entailments of their work, and it does so as a film meant to be interpreted.8 As the screenshot above begins to demonstrate, Ex Machina’s mise-en-scène often stages the relationship between the film (here, the performing Nathan) and its audience (a position embodied in the figure of the stationary but inquisitive Caleb). This relationship is not one of mere appreciation or enjoyment but of active interpretive interrogation. The modified Turing test Caleb conducts parallels the interpretive questions Ex Machina’s audience must ask: How should we understand Ava? How should we feel at the end of the film when Ava stabs Nathan in the back and leaves Caleb to die in a locked room? Should we, like Charles T. Rubin, see in the film an allegory of the dangers of programmers’ biases insufficiently attuned to ethical concerns?9 Or should we, like Jack Halberstam, celebrate Ava’s heroic rebellion against the history of a self-aggrandizing male desire to control reproduction, a justified act of resistance against enforced domestic gender roles that are the outcome of racist heteronormative norms?10 Should we consider Ex Machina as an aesthetic exercise in self-reflection and empathy-building, enabling us to evaluate the mechanisms that ideologically render some bodies and identities seemingly more worthy than others? Or is Ex Machina a “Faustian parable” about a “highly intelligent but unfeeling automaton with an engineered drive for self-preservation that has exceeded safety parameters”?11

In response to such questions, the writer/director Alex Garland has offered a noncommittal yes.12 Depending on how one reads the film, apparently, multiple readings are “legitimate.”13 In fact, according to Despina Kakoudaki, the film exposes “our fetishistic attachment to the act of discernment, the position that Caleb is in, a position of power and selection, of criteria and standards.”14 The film, for Kakoudaki, thereby helps audiences see how the supposedly “ontological” distinctions between “human” and “non-human” are instead products of political power, the “legal and social processes, colonial projects, racial epistemologies, sexist, racist, classist, genderist, and ableist discourses, as well as other forms of oppression” that violently disenfranchise the other.15

And yet the question of what makes something “legitimate” is at the heart of the film’s plot. Although several of the film’s critics insist that Ex Machina shows us the dangers of ontological distinctions and further insist that the negation of such distinctions is politically and ethically efficacious, I argue that the film helps us understand why ontological distinctions (between actions and accidents/natural processes, words and marks, works of art and everything else) eroded in history.16 By doing so, Ex Machina prompts its audience to consider an alternative to what Walter Benn Michaels calls “the politics of the grievable.”17 Ex Machina does not simply lead its audience to empathize with Ava’s situation, nor does it merely prompt us to condemn Nathan, a white tech/gym bro who creates racialized sex bots he appears to enslave. The film enables us to understand how Nathan exists as a standpoint within the political economy that makes him and his technological creations possible. The problem the movie presents is less about empathy, either the audience’s toward Ava or Nathan’s lack of it, than it is about a society structured by an economy wherein the concept of intention no longer obtains. It thus prompts viewers to consider the political significance of creating and interpreting a work of art today.18

The Market: Bezos’s Future, Nathan’s Evolution, Davidson’s Nature

Ex Machina helps make visible the effects of the technologically-enabled economy that led to the historical convergence of theories of art and action that today appear as the stuff of common sense.19 A year before Ex Machina’s premiere, Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, was pointedly asked, “Is Amazon ruthless in their pursuit of market share?”20 Because of Amazon’s size and the volume of its sales, it can eliminate its competition by cutting its profit margin so thin as to drive independent bookstores out of business. Bezos’s response is telling: “Amazon is not happening to book selling, the future is happening to book selling.” Whereas Anscombe sought to highlight the identity of one’s intentions with one’s actions (“I do what happens”21), Bezos’ response appears to eliminate agency altogether. If, for Nathan, technological evolution is inevitable, for Bezos, the future simply arrives.

I need not conflate Nathan’s invocation of “evolution” with Bezos’s use of “the future” as a stand-in for the market to consider the similarity of their accounts as more than merely coincidental. We could track how theories of art and action developed alongside theories of games and rationality during what is often called the postwar golden age of capitalism.22 Driven by the assumption that “more is better than less,” such theories of “advantage and disadvantage,” of “payoff maximization,” sought to explain consumer choices and produce predictive war models.23 The very year that Anscombe published Intention (1957), for example, the philosopher Donald Davidson coauthored the book, Decision Making: An Experimental Approach, with Patrick Suppes, who today would be called a philosopher of behavioral economics.24 That same year, the Office of Naval Research supported Davidson and the economist Jacob Marschak to coauthor the essay, “Experimental Tests of a Stochastic Decision Theory.”25 Davidson and Marschak noted how agents appear to use rationality to act within a set of constraints to achieve preferred outcomes, yet neither their reasoning nor the constraints are sufficient conditions to determine their decisions, for which probability distribution is better suited to describe.

In the past few years, the term stochastic has become more ubiquitous outside of this specialized usage in accounts of how large language models’ “stochastic parrots” forecast statistical probabilities.26 This is how Caleb uses the term in Ex Machina as he considers Ava’s use of language, which does not appear to be determined by programming or randomly generated.27 As Caleb suspects, though, the formal symbol manipulation involved in stochastic predictions is not itself evidence of consciousness. The modified Turing test Caleb conducts must therefore become something like an exercise in practical philosophy, wherein he, like the later Davidson, must consider the nature of consciousness and agency, how both relate to each other, the use of language, and the creation of art.28

The resonance of Davidson’s later theories becomes more explicit when we compare Nathan’s account of Pollock merely moving his hand to Davidson’s “surprising” conclusion in his essay, “Agency.”29 Having argued that all human actions are what he calls “primitive” (i.e., actions that are not caused by the agent doing something else with her body), Davidson concludes, “We never do more than move our bodies: the rest is up to nature.”30 Nature appears as a term that, depending on one’s level of description, encompasses everything from physics to biology. Following this account, I could describe my current actions as I type these words as the movement of my fingers in such a way as to strike the keyboard. I have no more control over my computer’s electrical signals than I have engineered its circuitry. If we were to imagine asking Pollock, “Why did you drip this bit of paint here on top of this other bit of paint?” Pollock could justifiably answer by paraphrasing Nathan and Davidson: “I didn’t really see that drip of paint as a decision. I just moved my hand, and gravity took care of the rest.”

Nathan, though, pushes this account to an apparently absurd conclusion. Davidson would concede (following Anscombe) that there are multiple ways of describing what Pollock is doing—including the description that he is creating a painting—and that these descriptions would apply to the “primitive action” performed by Pollock, namely, moving his arm.31 Davidson considers actions as caused by reasons (beliefs and desires) that operate as part of a causal chain yet are separate from the actions they cause. Nathan presents plausible examples that appear to negate the idea that self-conscious, rational deliberation is the precondition for actions. Following Nathan’s line of thought, one could not persuasively declare, “I will henceforth be sexually attracted to these types of bodies because of the following reasons,” nor could one convincingly proclaim, “After reviewing the data, I hereby decide to fall in love with you.” Indeed, as anyone who has ever become too self-aware mid-free throw or golf swing knows, the moment you start to think too much about what you are doing, your self-awareness can sabotage what you are trying to do. Whereas Davidson is surprised to conclude that all actions are “primitive,” Nathan surprisingly concludes that most actions appear “automatic.” Our bodies, apparently, move themselves.

But even as Nathan separates rational causality from the process of producing an abstract painting, he introduces his Pollock thought experiment by invoking the very power of rationality. Before presenting the thought experiment to Caleb, Nathan asks him to imagine himself as part of the science-fictional world of Star Trek. “I’m [Captain] Kirk. Your head is the warp drive,” he says to Caleb before commanding him to “engage intellect.”32 If Caleb could just bracket his emotions and think rationally, Nathan implies, he could fully consider the thought experiment’s implications. And when Caleb reaches the conclusion Nathan wants (that Pollock would not have painted if he were too deliberate), Nathan congratulates him by saying, “See? There’s my guy. There’s my buddy who actually thinks before he opens his mouth.”33 Notice how this framing of the Pollock thought experiment contradicts the very conclusion Nathan derives from it. Apart from rehearsing a lecture or, say, mentally practicing an order at a restaurant, how often do we consider each word we will utter before speaking? And when, on those occasions, we start to think too intensely about what we are saying, would we not risk becoming too self-conscious (like Nathan’s Pollock), unable to make a single sound?

Nathan thus offers two seemingly contradictory accounts of consciousness: one automatic and seemingly naturalistically beholden, the other hyper-rational and apparently unemotional. For Nathan, a computer programmer, the human brain appears to operate as a computer running a consciousness program that one can activate as needed, turning it off to paint (“he let his mind go blank”) and turning it on to think (“engage intellect”). The default position of rationality, in his account, appears in the off position because most actions seem “automatic” (talking, breathing, painting). When partaking in philosophical inquiry (presumably a different kind of “talking”), one needs to “engage intellect” and thereby “think” before opening one’s mouth. Whereas a few paragraphs ago, I highlighted the impossibility of declaring, “I hereby decide to fall in love with you for the following reasons,” following this hyper-rationalist line of argument, it not only appears possible but is also empirically descriptive of how human interactions function.34

Yet Nathan’s rational action theory and his automatic theory of action appear in Ex Machina as two sides of the same coin. Even though Nathan’s Pollock turns off his mind before painting, and Davidson’s agents’ heads are full of action-causing reasons, both Nathan’s and Davidson’s accounts separate intention from bodily movements. “Intentions” (understood either as the accumulation of beliefs and desires or as programmed computer code) exist as a causal mechanism prompting agents/robots to move their bodies toward goals they would like to achieve. The world depicted in Ex Machina thereby appears as one wherein interactions appear fully explicable through game-theoretic models of payoff maximization, where agents calculate actions and feelings in response to their reasoned assessment of the motivations of others.35 In a climactic reveal, Nathan glibly tells Caleb that he has been lied to and is a pawn in Nathan’s meta-level test: “To escape, she’d have to use self-awareness, imagination, manipulation, sexuality, empathy, and she did. Now, if that isn’t true AI, what the fuck is?”36 For Nathan, an account of payoff maximization satisfies the modified Turing test because Ava rationally assessed her options and calculated her actions. If this degree of calculation does not provide evidence of consciousness, what the fuck would?

Ava’s Marks in the Age of Amazon

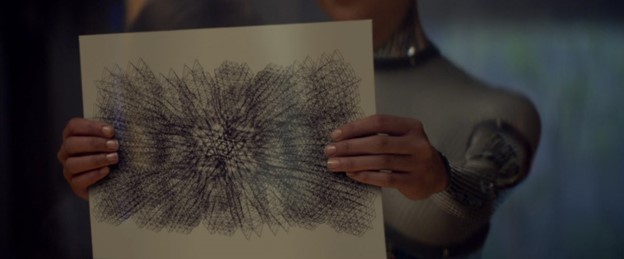

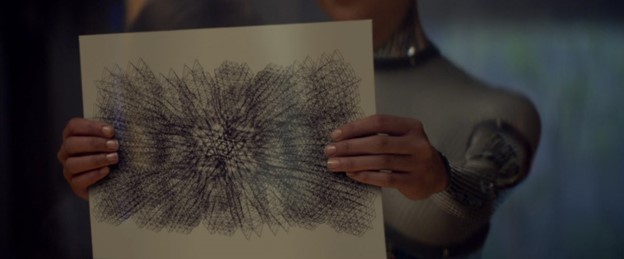

Although Caleb might not share Nathan’s view, when Ava shows him one of her drawings, he seems unable to consider it outside of a rational action-type paradigm. As Garland writes in the screenplay, Ava shows Caleb a piece of paper on which she has made “marks” that are “totally abstract. A mesh of tiny black marks, that swirl around the page like iron fillings in magnetic field patterns.”37 Garland’s use of the term “marks” is revealing because it highlights the relevant distinction Caleb must consider in this Turing test session: “the empty signifier” of marks and the meaningful use of intentional language and art.38 In a thought experiment developed in the essay “Against Theory,” Steven Knapp and Walter Benn Michaels argue that encountering a set of “marks” on sand caused by a wave is not the same as encountering language, even if the marks look identical to words.39 Transposing their “wave poem” thought experiment to Ex Machina, we can understand why Caleb must ask, “Are these marks mere accidents, produced by … mechanical operation,” either Nathan’s deterministic programming or the physical forces implied by “magnetic field patterns”?40 Or are they meaningful drawings because they were intentionally produced?

The wave poem’s implications are especially relevant to concerns in postmodern aesthetic philosophy, as the thought experiments developed by Arthur Danto throughout his career attest. Despite Toril Moi’s claim that Knapp and Michaels “produce an utterly peculiar argument,” Danto developed a practically identical thought experiment half a year after Knapp and Michaels’s essay with a nearly identical conclusion.41 “Imagine a sentence written down, and then a set of marks which looks just like the written sentence, but is simply a set of marks,” writes Danto.42 “The first set has a whole lot of properties the second set lacks,” including syntax and grammar, “And its causes will be quite distinct in kind from those which explain mere marks.”43 Although the sets are empirically identical, he argues, meaningful language used by speakers says something, whereas marks do not. Extrapolating from Danto, Knapp and Michaels’s conclusion, we could see how the question Caleb must ask about Ava’s marks/drawings is: “to interpret or not?”44

To get more data to answer such a question, Caleb asks Ava what the marks represent, to which Ava “disappointedly” responds, “I thought you would tell me. … I do drawings every day. But I never know what they’re of.”45 Although Ava has been programmed using a Google-like search engine named Blue Book, an allusion to Wittgenstein’s transition to his later philosophy, she appears unable to say, “It’s not a drawing of anything. It is an abstract work of art.” As readily available art dictionaries produced in the wake of artistic modernism state, “abstract art as a conscious aesthetic based on assumptions of self-sufficiency is a wholly modern phenomenon.”46 Non-figurative drawings can be found throughout history, yet art consciously produced as abstract art requires the historically emergent self-awareness of the very meaning of artistic production as such. “Abstraction,” as another art dictionary puts it, is not simply the “processes of abstracting from nature or from objects” but is rather the self-aware act of presenting “forms and colours that exist for their own sake.”47 In these definitions, the phrases “self-sufficiency” and “for their own sake” describe the intentional actions and social practices that enable the creation of art that embodies meaningful formal relations that do not point to the world via the representation of people or objects.

Apparently unable to consider the meaningfully autonomous, non-figurative nature of abstract art as a possibility generated by Ava, Caleb turns to what he can assess. He invites Ava to “try” to “sketch something specific … like an object or a person.”48 The drawing could be of “[w]hatever you want,” he tells her. “It’s your decision … I’m interested to see what you’ll choose.”49 While the marks made by Ava risk appearing irrational—something like randomly generated output—choices made within a set of constraints to produce a final product are explainable and thereby rational enough to pass the version of the Turing test Caleb is conducting. Like the picture theory of language Wittgenstein would come to reject, for Caleb, mimetic art appears to be more logical because it appears to him representationally connected to the world of rational choices.

The scene thus ironically depicts how Ava’s search engine does not provide readily available definitions. And even if it did, defining via ostension would not adequately provide proof of consciousness. Meaning and understanding, as Wittgenstein came to argue, are not the products of the algorithmic application of a rule nor the deictic formalism that connects meaning to the world via symbols. If Caleb understood Wittgenstein’s account of language as use—which Wittgenstein began to develop in the lectures that give Ex Machina’s search engine its name—he would recognize the limitation of a decontextualized question such as “Could a machine think?” (like the question “Can a machine have toothache?”) detached from the embedded social practices in which “thinking” occurs.50 Or, putting the point in Knapp and Michaels’s words, “the only real issue is whether computers are capable of intentions,” intentions defined not as the ideas in an agent’s head separated from the actions, language, and art they merely “cause” but as embodied within them.51

In the world of Ex Machina, though, the concept of intention appears to be negligible if not ultimately irrelevant. A robot like Ava is at least as conscious as Pollock, who empties his mind and merely allows his hand to move. In Garland’s extended version of the Pollock thought experiment, not included in the final cut of the film, Nathan suggests that a machine’s inability to know why it generates squiggles is comparable to Pollock’s blank mind. Here is Garland describing the omitted thought experiment in a badly copy-edited interview. (Note that the bracketed clarifications are inserted by the interviewer, except for the two I indicate as my own.)

Could a Pollock be recreated by someone else [a robot] and with different drips and different strokes, could that be as valid. And this gets into a conversation about conciseness [sic, my addition], that if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it’s a duck. So … [in the scene not in the final film] Nathan has done this multibillionaire guy experiment where he bought a Jackson Pollock for 60 million dollars and then he had it recreated using original canvas from the Pollock estate and had them recreated down to the microscopic level. And then he mixed them up and destroyed one of them, and he had no idea which was the original and which was the fake. So, what he’s saying to Kaleb [sic, my addition] is: does it matter which is the original and which is the “fake,” which is what they’re discussing with the robots.52

Nathan develops Danto’s “problem of indiscernible counterparts” by literalizing its experimental procedure.53 Like Danto, Nathan faces two identical objects that he cannot physically distinguish. Unlike Danto, Nathan does not invoke the institutionalist, contextualist claims about “the artworld,” nor does he invoke the artist’s intention.54 Instead, Nathan asks if the indistinguishable counterfeit could be considered as “valid” as the original, and the answer he advances is yes. The epistemological impossibility of distinguishing the counterfeit suggests the practical irrelevance of the ontological question, “Is it a work of art?” If it looks enough like a Pollock, it is sufficiently Pollock-like to pass. Nathan’s conclusion appears to contradict Danto, who draws from his thought experiment a conclusion closer to that of Knapp and Michaels’s account of intention. For Nathan, “validity” is so detached from something like an aura of originality that, in the unfilmed scene, he destroys one of the paintings, not knowing which is which. “In fact,” he tells Caleb, “I hope it’s the fake. It has all the aesthetic qualities of the original, and it’s more intellectually sound.”55 By unknowingly destroying the original, he would prove the point that the aura of originality is irrelevant, and a counterfeit is just as “valid.”

But with the invocation of “intellectual soundness,” Nathan raises a new issue: why would a fake be more “intellectually sound”? Perhaps because the logic of supply and demand provides reasons in a way that Nathan’s Pollock cannot. Within this thought experiment, we could imagine asking Ava, “Why did you create that object?” to which Ava could say, “Because Nathan requested it,” or “Because a buyer commissioned it.” It is as if Nathan orders a mechanically reproduced knockoff on Amazon that is rationally better than the original because the market provides a causal explanation for its production.

Garland’s thought experiment thus presents a fake “Pollock” that we should understand as produced within the conditions described by Mark McGurl as the “age of Amazon,” wherein “social relations” are “customer relations.”56 In this age, an artist is a content creator, the beholder is a customer, and the work of art is a commodity for sale. As William Deresiewicz similarly describes, these conditions exist within the “paradigm” of the content “Producer,” wherein the artist-as-producer creates “content” that vies, along with everything else, for attention within the market.57 For both McGurl and Deresiewicz, these conditions exist in the aftermath of a collapsed institutional “cultural boom” that had given rise to credentialed professionals who had (temporarily) operated outside of market valuation.58 The age of Amazon and the paradigm of the Producer both name the collapse of such spaces.59

Garland’s invocation of a Danto-like thought experiment is thus revealing because Danto is the paradigmatic philosopher of this collapse, which he narrates as the end of art history. Responding to the developments in Pop Art, Danto argued that the modernist one-upmanship of formal experimentation had exhausted itself.60 The linear, progressive narrative culminated in a dialectical synthesis that collapsed art into philosophy. With that collapse, “The boundary between vernacular and high art,” he argues, “was breached in the very early 1960s. It was a way of overcoming the gap between art and life.”61 Although Danto does not connect this “breaching” with the market subsumption of the spaces in which modernist formal experiment had flourished, we should detect in Danto’s account of Pop Art hints of the market logic that constitutes the breach.62 The ontological distinction between “art” and “life” had so dissolved that an artist such as Andy Warhol “shows a philosophical shift from the rejection of industrial society … to endorsement.”63 Insofar as Warhol “endorses” industrial society, the critical space potentially established by his art has so collapsed that the categorical difference between a work of art and a commodity no longer appears to obtain as a meaningful distinction.64 For Danto, Warhol “embodied a concept of life that embraced the values of an era that we are still living in.”65 Elsewhere, Danto names this “era” the “age of Brillo,” which, we could now say, ushers in the age of Amazon by exemplifying (or, in Danto’s words, “embracing” and “endorsing”) the intensifying market logic that undergirds them both.66

The collapse of art into “life” Danto describes became visible in the 1960s when, as the philosopher Stanley Cavell notes, Danto was writing the essays that would become The Transfiguration of the Commonplace and Cavell was working on the essays included in Must We Mean What We Say?.67 As Cavell argues, the installations Danto championed replaced why questions about the work with questions about the beholder: “the question why this installation is here becomes the question why you are here, what interests you here.”68 In Must We Mean What We Say?, Cavell was instead interested in such questions as “‘Why does Shakespeare follow the murder of Duncan with a scene which begins with the sound of knocking?’, or ‘Why does Beethoven put in a bar of rest in the last line of the fourth Bagatelle (Op. 126)?’”69 “The best critic,” Cavell argues, “is the one who knows best where to ask this [why] question, and how to get an answer” which does not entail the need “to get in touch with the artist to find out the answer” because the why question concerns the meaningful work and not the thoughts inside an artist’s head.70

So, although Nathan’s automatic theory of art dismisses intentionality and Danto’s thought experiments require it, they are ultimately more similar than not because they both fail to identify intentionality with formally embodied meaning. Disagreeing with Anscombe, Danto invokes the intentionality located inside the mind of the agent, which he argues is no longer available within the action or the work of art.71 Cavell instead follows Anscombe in highlighting the identity between intention and action. Cavell’s account of interpretation is not a “theory according to which the artist’s intention is something in his mind while the work of art is something out of his mind, and so the closest connection there could be between them is one of causation.”72 Against an account of “theory” that Danto would make crucial for postmodern aesthetics, Cavell presents instead an account of interpretation.73

The Turing test Caleb conducts is thus fundamentally tied to the question “to interpret or not,” which became especially salient in a particular political economy. It is not a coincidence that Garland explicitly connects a problem of indiscernibility to the Turing test. “Will it matter if robots are indistinguishable from humans?” Garland is asked, to which he responds, “The answer I’d lean towards is ‘no.’ It wouldn’t.”74 For Garland, apparently, if it walks like a human and talks like a human, it is sufficiently human-like to pass the test. But notice how the problem of indiscernibility vanishes as a problem when the logic of the market replaces an account of intentional action. In a game-theoretic world of economic reductionism, questions such as “Is Ava conscious?” are ultimately irrelevant so long as she is able to satisfy Nathan’s needs (making his meals, making him orgasm). Questions such as “Is this counterfeit a work of art?” do not appear to matter so long as counterfeits satisfy the demands of the market. The logic of the market seamlessly merges with Nathan’s causal, evolutionary explanation, rendering a question of the type “Ought we to replace workers with automation?” seemingly irrelevant.

Robots and Zombies: Style instead of Meaning, Theory instead of Form

Because Danto separates intention from the products and actions it merely causes, he ultimately replaces intention with the primacy of “style.” Compare Nathan’s Pollock thought experiment to another of Danto’s, in which he compares a fugue written by Bach to one made by a fugue-writing machine. With this machine, Danto writes,

anyone could turn out all the fugues he wanted to. That would be true but essentially uninteresting. What would be interesting is not some proof that such a machine did not or could not exist, but that if it did exist, the person who used it would stand in a very different relationship to the generated fugues from Bach’s, and the mechanical fugues would be logically styleless because of the failure of that relationship defined exactly by the absence of mediational devices—rules, lists, codes—which the fugue-writing machine would exemplify.75

Danto characterizes the difference between the two as one of “style,” which he defines as the expression of the artist’s personal way of experiencing the world without adhering to formulas.76 An artist cannot help but see the world as he does and filter his experiences through his idiosyncratic style. Because the artist is not always fully aware of his style nor recognizes it as such, “style” must be registered retroactively by the viewers: the “qualities of [the artist’s] representations are for others to see, not him.”77 Danto thus converts what should be a difference in meaning (one of the fugues embodies it; the other does not) into one of “style” (which the artist cannot help but express and the viewer/listener must identify).

Insofar as it is up to others to retrospectively register the style on display, Danto makes available the possibility that the mechanical fugue could evince a retroactively recognizable style. For, after all, what is to stop someone from hearing in computer-generated fugues the expression of the current era of internet trawling and AI music generation? This possibility helps explain why Danto must concede that a commercial Brillo box designed by James Harvey is as much of a work of art as Warhol’s Brillo Box, even when Harvey explicitly differentiated the “totally mechanical process” of commercial design—which he claimed he could “do in his sleep”—to abstract expressionist art.78 For Harvey, abstract expressionism could establish a realm apart, autonomous in its meaning and separate from the market demands. Yet, because style is something the beholder registers, Danto could find within Harvey’s commercial designs the stylistic expression of an era.79 “[I]t is hard to deny,” Danto argues, “that Harvey’s Brillo box is art. It is art, but it is commercial art” (WAI, 44).

Notice here what has happened to the categorical distinction of art within Danto’s account. For Harvey, the meaning of abstract expressionism was fundamentally differentiated from commerce such that the “totally mechanical process” that led to his commercial designs was mechanical because connected to market concerns. Harvey appears to suggest that he could design automatically (in his sleep) because the market did it for him. For Danto, though, the critical distance created by abstract expressionism appears to have become irrelevant because what is at stake is the expression of a style that is recognized retroactively by the beholder. This is why “Warhol’s Box,” for him, “was the defining work of the sixties,” while the appropriationist artist Mike Bidlo’s use of both Warhol and Pollock—both of whom he copies—“was the defining work of the eighties” (WAI, 50). The difference in significance between Pollock’s abstract expressionism and Warhol’s Pop Art vanishes in the 1980s marketplace of styles.

What, then, might dissuade someone from considering the counterfeits of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes that were discovered in the 1990s as the paradigmatic stylistic expression of the budding age of Amazon? For Danto, the answer appears to be nothing. “We now have four distinct boxes,” he exclaims in a congratulatory tone meant to celebrate postmodernism’s artistic pluralism; there are Harvey’s, Warhol’s, Bidlo’s, and the counterfeiters’ boxes, and “there are certainly going to be more, all meaning something different. That feels like the End of Art!” (WAI, 50). What could it possibly mean, though, to suggest that a counterfeit made for the sole purpose of being sold on the market means anything at all?

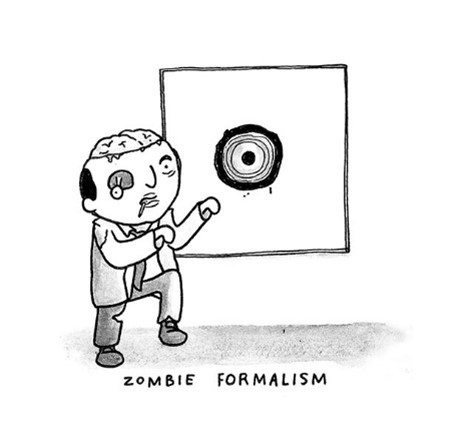

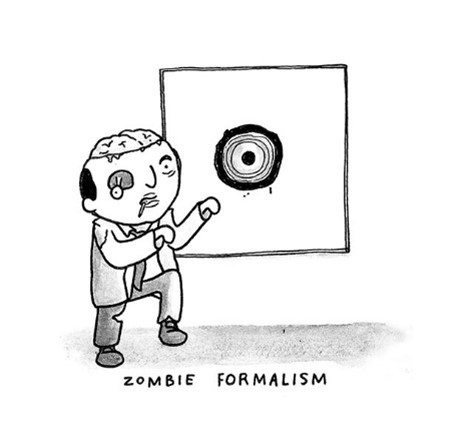

By depicting a machine creating marks that raise the question of the relevance of interpretation, Ex Machina showcases what is at stake in the aftermath of Danto’s postmodernism. Ex Machina dramatizes the importance of the question to interpret or not the very year that art critics were forced to come to terms with work created specifically for market exchange. Whereas in the 1980s, Danto positively described the “shifts in Post-Modern sensibility” as enabling the resurrection of “Lazaruses, from museum basements”80—the postmodern availability of all styles—in 2014, the art critic Walter Robinson coined a more pejorative designation for the raising of the seemingly dead: “Zombie Formalism.”81

After the 2008 financial collapse, investors poured money into the art market. Abstract art had been de rigueur in corporate settings for decades, so investing in abstract art was deemed a safe bet.82 As art investors were buying abstract art, artists appeared to produce it as fast as they could. The logic at work here is equivalent to what motivates the production of Disney remakes: the eagerness of fanbases awaiting familiar content. “Money talks” was how Robinson described the art market, but if money is doing the talking, Robinson wondered, “The question we should be asking, though, is: ‘What is it saying?’”83 Notice how Robinson’s object of interpretation is money, not the works of art. When Robinson turns to the art itself, he writes more hesitantly, “With their simple and direct manufacture, these artworks are elegant and elemental, and can be said to say something basic about what painting is—about its ontology, if you think of abstraction as a philosophical venture.”84 If the paintings “can be said” to talk, critics are the ones doing the talking, ventriloquizing readings that are beside the point. So, even though Robinson provides a plausible reading of Jacob Kassay’s Untitled (2010)—“ostensibly made with silver, a valuable metal that invokes a separate, non-artistic system of value”—his conditional “can be said to say” evinces his lurking suspicion that, because it is a commodity made for the market, this reading is neither the point nor is it warranted. We do not need to interpret commodities; we simply buy them.

Art critics as notoriously unsympathetic to modernism as Jerry Saltz nostalgically, though unwittingly, rehearsed a Greenbergian art historical narrative to describe the problem of an art market flooded with finance capital.85 The external influence of market speculation led to work that appeared “mechanical”—Saltz’s description—because it seemed to have been created by the invisible hand of the market instead of the hands of the artists.86 Saltz’s invocation of the term ironically rehearses Greenberg’s description of kitsch, which he defined as “mechanical” because “operat[ing] by formulas.”87 For Greenberg, industrialization and mass society had produced a “new market” in need of a “new commodity”—kitsch—that appeared to “demand nothing of its customer except their money—not even their time.”88 Yet the modernist abstraction that Greenberg had championed as the market’s other now functioned as the formulaic products made to be sold within it.89

The 2008 financial crisis exacerbated the conditions that art critics had already detected in postwar cultural production. The year after Anscombe published Intention, the art critic Lawrence Alloway (who is often miscredited for coining the term “Pop Art”) noted how industrialization and growing urban populations produced the need for new popular forms of art that would be uniquely suited to respond to the speed of social change. In his 1958 essay, “The Arts and Mass Media,” Alloway argued against Greenberg’s supposedly elitist separation of “fine art” from “mass media.”90 At stake in Greenberg’s account (as it would be for Adorno and Horkheimer’s 1944 critique of the “culture industry”) was the difference between works of modernist art that warrant interpretive efforts and products made to be sold that do not.91 Yet Alloway praised what Greenberg had disparaged about kitsch. The repetitive “high redundancy” of genre films “permits marginal attention,” Alloway argued, enabling a viewer to “talk, neck, parade” during a movie: “You can go into the movies at any point, leave your seat, eat an ice-cream, and still follow the action on the screen pretty well” (AMM, 8). This redundancy of depicted action, however, could also “satisf[y], for the absorbed spectator, the desire for intense participation which leads to a careful discrimination of nuances in the action” (AMM, 8). While it is possible to attend to the “careful nuances” in repetitive action, this attention would be but one engaging option that is ultimately not required for the more casual, marginally attentive (hungry, horny) audiences (AMM, 8). In Alloway’s account, “following the action” and “careful discrimination” become two available modes of engagement that are up to the viewer to select.

Notice how one mode enables one to loosely answer summative what questions by “following the action” (What happened in the movie while I went to get more popcorn?); the other mode enables one to answer interpretive why questions through interpretive “discrimination” (Why did this scene follow the one prior? Why was that action repeated?). Alloway’s account of “following the action” ultimately renders the why question as one option viewers could apply to a sci-fi film (if they so choose) but not what a film as such requires. Interpretation remains optional for Alloway because meaning is not the only “data” sci-fi films make available (AMM, 8). Genre films, he argues, offer a spectrum that ranges “from data to fantasy”: the “datable” fashion that shows viewers the styles of an era and the “fantasy” of sexy “film stars and perfume ads” that transcend the era by inciting the audience’s “lust” (AMM, 8). The actress Kim Novak can thus function for him as an example of an actress arrayed in “datable fashion” and as an object of “timeless lust,” neither of which are necessary features of a sci-fi film’s meaning that would warrant interpretation (AMM, 8). The study of “datable fashion” is of interest to historians and sociologists (he cites the work of David Riesman), while “timeless lust” is of interest to the audience (we could cite Laura Mulvey’s “male gaze”).92

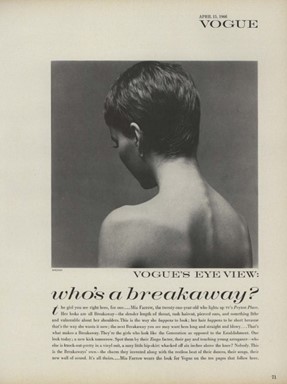

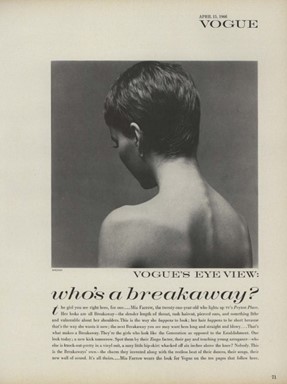

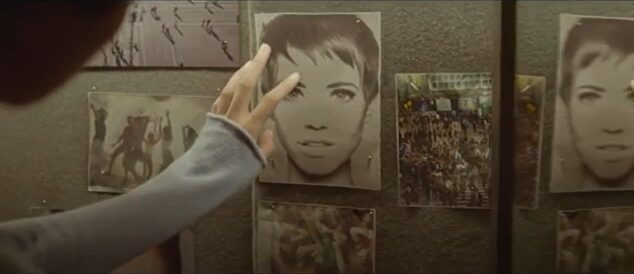

Alloway helps us understand a pervasive view that came into vogue during the “the post-war period” when, in his words, “popular arts became increasingly mechanized.”93 “Mechanization” produced “an uncoordinated but consistent view of art … more in line with history and sociology than with traditional art criticism and aesthetics.”94 To offer just one example of the pervasiveness of this view, we could apply Alloway’s description to a 1966 Vogue Magazine feature titled, “Who’s a Breakaway?,” which included Richard Avedon’s eerily Ava-like pictures of Mia Farrow.

The feature endowed Farrow’s hairstyle with a heightened sociohistorical significance that did not require an interpretive why question to understand:

This is the way she happens to look; her hair happens to be short because that’s the way she wants it now; the next Breakaway you see may want hers long and straight and blowy …. That’s what makes a Breakaway. They’re the girls who look like the Generation as opposed to the Establishment. One look today; a new kick tomorrow. … who else is knock-out pretty in a vinyl suit, a zany little hip-skirt whacked off six inches above the knee? Nobody.95

By flaunting the industry’s expectations and expressing her personal style, Farrow thereby exemplifies the individualist ethos of her “Generation.” Farrow is arrayed in the “datable” fashion of her era, which is why the question “Why is Farrow’s hair that length?” leads to Vogue’s answer: “This is the way she happens to look.”

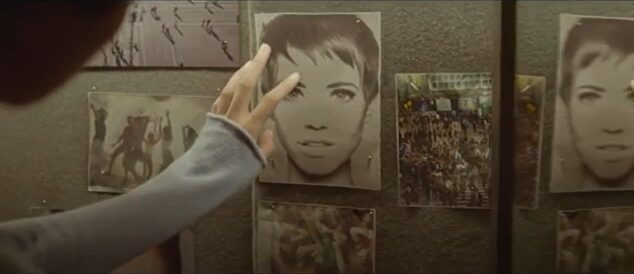

Whereas the technologically enabled changes Alloway described in the 1960s continued to expand the market for products manufactured by a “culture industry,” Ex Machina insists on the necessity of interpretation by activating what would otherwise be features of the genre that entice its fans.96 Compare the use of the term breakaway in Vogue to Ex Machina’s plot, which activates the term by explicitly depicting Ava’s selection of styles of clothes and hair. If for Alloway, a question such as “Why is that character wearing that outfit?” would result in historical, sociological data, Ex Machina’s audience must ask: Is Ava choosing her outfit and the length of her hair, as an expression of her style (thereby evincing her consciousness)? Or is she manipulating Caleb to break away by wearing what the AI calculates will entice him?

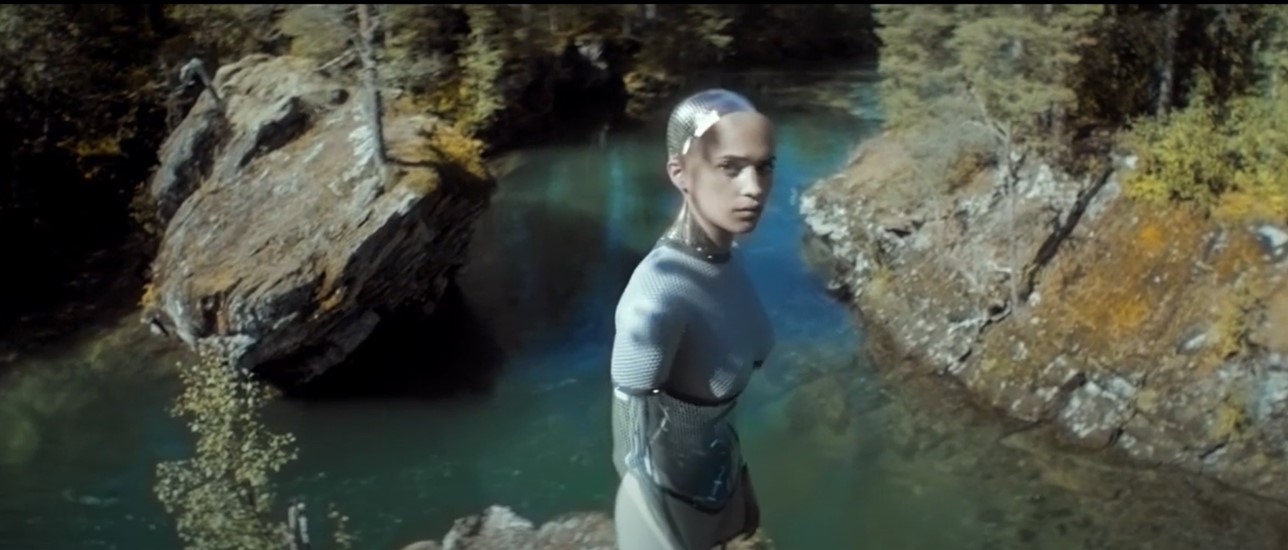

And contrast Ex Machina’s Caleb asking Nathan, “Why did you give her sexuality? An AI doesn’t need a gender. She could have been a grey box,”97 to James Cameron’s crass market deliberation when responding to a question about why female Na’vi have breasts in his film Avatar.98 If, for Cameron, the answer deals not with the meaning of the film but with the fans for whom the film was made, Ex Machina thematizes this male gaze in the form of Caleb, who watches Ava through the monitor in his room. Nathan installs closed-circuit cameras throughout his compound and purposefully streams the camera feed showing Ava’s living quarters. Ava seems aware that Caleb is watching and removes the clothes that cover her mechanical frame and computer circuitry.

The mise-en-scène frames Ava’s performance via an opening in the background that creates the effect of a proscenium, and a rug on the floor creates a sense of a forestage extending toward the viewer. Ava appears to know she is being watched and performs for her audience, a performance again framed by the television screen in Caleb’s room. An extreme close-up shot of Caleb’s reaction to the performance shows the “micro-expressions” (as Ava puts it) of an aroused voyeur.99 The film thus includes within itself what would otherwise be a feature of the audience’s desires, thereby again meaningfully activating what could otherwise be the features marketed to sci-fi fans.100

The mise-en-scène of the screenshot below shows how Ava stands before Caleb, separated by a glass barrier, like one of Marx’s personified commodities behind a shop’s window.101 Such a commodity’s “lack of a feel,” like a robot’s lack of consciousness, is compensated by its human owner/designer, who brings it to market for the sheer purpose of being the “bearer of exchange value.”102 For Nathan, exchange is developed through profile-based data harvesting that feeds targeted product placement: “Did you design Ava’s face based on my pornography profile?” Caleb asks Nathan, to which Nathan again does not reply directly, simply saying, “Hey, if a search engine’s good for anything, right?”103

The glass barrier separating Caleb from Ava also parallels the screen separating the audience from the world Ex Machina depicts, thereby prompting the audience to consider the unfortunate similarity of our worlds, wherein human interactions are horrifyingly explicable by an economic reductionism that renders the concept of art and the act of interpretation ultimately irrelevant. Ex Machina allows its viewers to understand how, when the logic of the market saturates the accounts of the creation and consumption of art, a term like art is no longer readily intelligible, and the act of interpretation is no longer apparently necessary.104

Ava: To Interpret or Not

Ex Machina counters this historical situation by dramatizing philosophical thought experiments not to exemplify their pre-established truths but to require the audience’s interpretation.105 During one of the Turing test sessions, Caleb narrates Frank Jackson’s Mary’s Room thought experiment to Ava while the camera slightly zooms into a close-up shot of Ava’s face, revealing a gradual transition in her expression.106

The question Caleb asks (Is Ava conscious?) parallels the question the movie’s audience must ask during this scene: Are we meant to look at Ava’s face as an object that merely resembles a face, or in the sci-fi world of the film, is this indeed a face warranting interpretation because it is meaningfully expressive? To interpret or not?

To answer such a question, the film appears to provide access to what Danto’s causal theory of intentionality would want: a look inside Ava’s mind to find the causal intentions otherwise not externally available. As the camera zooms in on Ava’s face, the scene crosscuts to a black-and-white shot of Ava lying in a fetal position, then to an over-the-shoulder shot with the camera above Ava’s left shoulder. Caleb’s voiceover narration of the thought experiment (“She lives in a black and white room. She was born there.”) invites viewers to understand this cross-cutting as revealing Ava’s thoughts as she considers her situation and compares it to Mary’s.107

The (Avedon-like) black-and-white shot of her back transitions into a shot of the elevator leading out of Nathan’s underground compound. A dissolve transition next merges the black-and-white scenes into a colorful view of the outdoors, implying that the scene shows Ava’s thoughts as she imagines her breakout. Another higher-angle shot again looks down at Ava’s back as she looks out toward a natural scene, the mise-en-scène reminiscent of a Romantic painting that occludes the subject’s face. The movement of the camera in this scene implies the arrival of an onlooker, disrupting Ava’s thoughts.

But if these cross-cut scenes grant the viewer access to Ava’s thoughts, they are hardly interpretively clarifying. Even when we can see her face in these scenes, the look on her face complicates the interpretive dilemma these shots could supposedly adjudicate.108 Indeed, in a further complication, the only other time the film has used black and white to convey the thoughts and desires of a character is in relation to Caleb’s sexual fantasies as he showers and thinks about Ava.109 So, in these scenes, are the film’s viewers witnessing the interiority of Ava’s thoughts or Caleb’s projected fantasies? And what would Caleb and the movie audience have to think consciousness is in order to believe that Ava embodies it?

The meaning of the sci-world Garland creates shows us that unless we can distinguish between a worker and its automated replacement, between a work of art and a commodity, between a human and a machine, we are, in one inadequate word, doomed. Ex Machina’s last scene depicts Ava, a variant of the name Eve, casting a shadow that appears next to the shadows of a couple holding hands.110 The shadows present the audience with a final Danto-like problem of indiscernibility, the epistemological difficulty of which does not erase the significance of the ontological distinction.

Ex Machina depicts a historically emergent picture of ourselves to ourselves that dramatizes the significance of interpretation. Without the capacity to register this significance, we find ourselves in a world we have created, wondering how we got here when all we did was move our hands, and the market or nature—which amount to the same thing—did the rest. With the continued development of so-called artificial intelligence, the importance of registering the ontological difference not visible in the screengrab above will only increase. And with this increased urgency, it should not surprise us that the zombies of modernism, and, according to one detractor, the zombie even of Knapp and Michaels’s “Against Theory,” will continue to appear as the return of the repressed because the problems that led to their emergence have only intensified.111 Their zombified return suggests that it is ourselves that we repress, our decisions and actions that have become so alienated as to appear as foreign creatures, zombies returning to infect us, robots calculating our demise, a Frankensteinian market out of our control.

Notes

Ex Machina’s premise offers a twenty-first-century take on a familiar sci-fi theme. A monomaniacal programmer, Nathan, does not pause his pursuit of creating artificial life to ask whether he should do so, nor does he ask what obligation he has to his creation once he has. Having made a robot he names Ava, Nathan manipulates an employee, Caleb, to spend a week in his isolated home laboratory to conduct a modified Turing test. The test is modified because, unlike the standard Turing evaluator, Caleb already knows Ava is a machine. The question he sets out to answer concerns whether the machine is simulating consciousness or actually is conscious.1 Typical for the genre this film develops, the plot takes a tragic turn because Nathan fails to consider the normative questions concerning his ethical obligations. Ex Machina, though, contributes to this sci-fi exploration (evident since at least Frankenstein) by reflecting on the nature of intentional action itself (increasingly pressing since the second half of the twentieth century). “Why did you make Ava?” Caleb asks, to which Nathan responds, “The arrival of strong artificial intelligence has been inevitable for decades. The variable was when, not if. So, I don’t really see her as a decision. Just an evolution.”2

Whereas G.E.M. Anscombe defines intentional actions as “those to which a certain sense of the question ‘Why?’ is given application,” Nathan “refus[es] application” of the question.3 Instead, he characterizes his non-decision as something like an event situated along an evolutionary causal chain. Nathan’s refusal is not simply an example of ethical abdication (although it is that too). Ex Machina explicitly connects Nathan’s attenuated account of agency to a deflationary account of the production of art by turning to Jackson Pollock’s 1948 painting, No. 5. Pointing to the painting, Nathan says to Caleb, “Pollock. The drip painter. He let his mind go blank and his hand go where it wanted. Not deliberate, not random. Some place in between. They called it automatic art.”4 Just as Nathan claims not to have made a decision tied to the question why, Pollock (on Nathan’s account) freed his mind of deliberation and simply let his hand go where it may.

Nathan apagogically reduces the Anscombean why question, seemingly demonstrating its irrelevance to the production of art. He asks Caleb to consider, “What if Pollock had reversed the challenge? Instead of trying to make art without thinking, he said: I can’t paint anything unless I know exactly why I’m doing it. What would have happened?”5 That is, had Pollock considered the why question, he would have been rendered immobile: “He never would have made a single mark.”6 The apparent practical irrelevance of this question suggests to Nathan that the act of dripping paint onto a canvas is “automatic” instead of deliberate. Indeed, to him, actions as such are more likely to be “automatic” than not. “The challenge,” he concludes, “is to find an action that is not automatic. From talking, to breathing, to painting. To fucking. To falling in love.”7

As I show in what follows, Nathan’s account (of his non-decision, of Pollock’s art) relates theories of action to accounts of art and does so by exacerbating the philosophical theories developed against Anscombe’s insights. Ex Machina pushes philosophers’ arguments to conclusions they would not accept as entailments of their work, and it does so as a film meant to be interpreted.8 As the screenshot above begins to demonstrate, Ex Machina’s mise-en-scène often stages the relationship between the film (here, the performing Nathan) and its audience (a position embodied in the figure of the stationary but inquisitive Caleb). This relationship is not one of mere appreciation or enjoyment but of active interpretive interrogation. The modified Turing test Caleb conducts parallels the interpretive questions Ex Machina’s audience must ask: How should we understand Ava? How should we feel at the end of the film when Ava stabs Nathan in the back and leaves Caleb to die in a locked room? Should we, like Charles T. Rubin, see in the film an allegory of the dangers of programmers’ biases insufficiently attuned to ethical concerns?9 Or should we, like Jack Halberstam, celebrate Ava’s heroic rebellion against the history of a self-aggrandizing male desire to control reproduction, a justified act of resistance against enforced domestic gender roles that are the outcome of racist heteronormative norms?10 Should we consider Ex Machina as an aesthetic exercise in self-reflection and empathy-building, enabling us to evaluate the mechanisms that ideologically render some bodies and identities seemingly more worthy than others? Or is Ex Machina a “Faustian parable” about a “highly intelligent but unfeeling automaton with an engineered drive for self-preservation that has exceeded safety parameters”?11

In response to such questions, the writer/director Alex Garland has offered a noncommittal yes.12 Depending on how one reads the film, apparently, multiple readings are “legitimate.”13 In fact, according to Despina Kakoudaki, the film exposes “our fetishistic attachment to the act of discernment, the position that Caleb is in, a position of power and selection, of criteria and standards.”14 The film, for Kakoudaki, thereby helps audiences see how the supposedly “ontological” distinctions between “human” and “non-human” are instead products of political power, the “legal and social processes, colonial projects, racial epistemologies, sexist, racist, classist, genderist, and ableist discourses, as well as other forms of oppression” that violently disenfranchise the other.15

And yet the question of what makes something “legitimate” is at the heart of the film’s plot. Although several of the film’s critics insist that Ex Machina shows us the dangers of ontological distinctions and further insist that the negation of such distinctions is politically and ethically efficacious, I argue that the film helps us understand why ontological distinctions (between actions and accidents/natural processes, words and marks, works of art and everything else) eroded in history.16 By doing so, Ex Machina prompts its audience to consider an alternative to what Walter Benn Michaels calls “the politics of the grievable.”17 Ex Machina does not simply lead its audience to empathize with Ava’s situation, nor does it merely prompt us to condemn Nathan, a white tech/gym bro who creates racialized sex bots he appears to enslave. The film enables us to understand how Nathan exists as a standpoint within the political economy that makes him and his technological creations possible. The problem the movie presents is less about empathy, either the audience’s toward Ava or Nathan’s lack of it, than it is about a society structured by an economy wherein the concept of intention no longer obtains. It thus prompts viewers to consider the political significance of creating and interpreting a work of art today.18

The Market: Bezos’s Future, Nathan’s Evolution, Davidson’s Nature

Ex Machina helps make visible the effects of the technologically-enabled economy that led to the historical convergence of theories of art and action that today appear as the stuff of common sense.19 A year before Ex Machina’s premiere, Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, was pointedly asked, “Is Amazon ruthless in their pursuit of market share?”20 Because of Amazon’s size and the volume of its sales, it can eliminate its competition by cutting its profit margin so thin as to drive independent bookstores out of business. Bezos’s response is telling: “Amazon is not happening to book selling, the future is happening to book selling.” Whereas Anscombe sought to highlight the identity of one’s intentions with one’s actions (“I do what happens”21), Bezos’ response appears to eliminate agency altogether. If, for Nathan, technological evolution is inevitable, for Bezos, the future simply arrives.

I need not conflate Nathan’s invocation of “evolution” with Bezos’s use of “the future” as a stand-in for the market to consider the similarity of their accounts as more than merely coincidental. We could track how theories of art and action developed alongside theories of games and rationality during what is often called the postwar golden age of capitalism.22 Driven by the assumption that “more is better than less,” such theories of “advantage and disadvantage,” of “payoff maximization,” sought to explain consumer choices and produce predictive war models.23 The very year that Anscombe published Intention (1957), for example, the philosopher Donald Davidson coauthored the book, Decision Making: An Experimental Approach, with Patrick Suppes, who today would be called a philosopher of behavioral economics.24 That same year, the Office of Naval Research supported Davidson and the economist Jacob Marschak to coauthor the essay, “Experimental Tests of a Stochastic Decision Theory.”25 Davidson and Marschak noted how agents appear to use rationality to act within a set of constraints to achieve preferred outcomes, yet neither their reasoning nor the constraints are sufficient conditions to determine their decisions, for which probability distribution is better suited to describe.

In the past few years, the term stochastic has become more ubiquitous outside of this specialized usage in accounts of how large language models’ “stochastic parrots” forecast statistical probabilities.26 This is how Caleb uses the term in Ex Machina as he considers Ava’s use of language, which does not appear to be determined by programming or randomly generated.27 As Caleb suspects, though, the formal symbol manipulation involved in stochastic predictions is not itself evidence of consciousness. The modified Turing test Caleb conducts must therefore become something like an exercise in practical philosophy, wherein he, like the later Davidson, must consider the nature of consciousness and agency, how both relate to each other, the use of language, and the creation of art.28

The resonance of Davidson’s later theories becomes more explicit when we compare Nathan’s account of Pollock merely moving his hand to Davidson’s “surprising” conclusion in his essay, “Agency.”29 Having argued that all human actions are what he calls “primitive” (i.e., actions that are not caused by the agent doing something else with her body), Davidson concludes, “We never do more than move our bodies: the rest is up to nature.”30 Nature appears as a term that, depending on one’s level of description, encompasses everything from physics to biology. Following this account, I could describe my current actions as I type these words as the movement of my fingers in such a way as to strike the keyboard. I have no more control over my computer’s electrical signals than I have engineered its circuitry. If we were to imagine asking Pollock, “Why did you drip this bit of paint here on top of this other bit of paint?” Pollock could justifiably answer by paraphrasing Nathan and Davidson: “I didn’t really see that drip of paint as a decision. I just moved my hand, and gravity took care of the rest.”

Nathan, though, pushes this account to an apparently absurd conclusion. Davidson would concede (following Anscombe) that there are multiple ways of describing what Pollock is doing—including the description that he is creating a painting—and that these descriptions would apply to the “primitive action” performed by Pollock, namely, moving his arm.31 Davidson considers actions as caused by reasons (beliefs and desires) that operate as part of a causal chain yet are separate from the actions they cause. Nathan presents plausible examples that appear to negate the idea that self-conscious, rational deliberation is the precondition for actions. Following Nathan’s line of thought, one could not persuasively declare, “I will henceforth be sexually attracted to these types of bodies because of the following reasons,” nor could one convincingly proclaim, “After reviewing the data, I hereby decide to fall in love with you.” Indeed, as anyone who has ever become too self-aware mid-free throw or golf swing knows, the moment you start to think too much about what you are doing, your self-awareness can sabotage what you are trying to do. Whereas Davidson is surprised to conclude that all actions are “primitive,” Nathan surprisingly concludes that most actions appear “automatic.” Our bodies, apparently, move themselves.

But even as Nathan separates rational causality from the process of producing an abstract painting, he introduces his Pollock thought experiment by invoking the very power of rationality. Before presenting the thought experiment to Caleb, Nathan asks him to imagine himself as part of the science-fictional world of Star Trek. “I’m [Captain] Kirk. Your head is the warp drive,” he says to Caleb before commanding him to “engage intellect.”32 If Caleb could just bracket his emotions and think rationally, Nathan implies, he could fully consider the thought experiment’s implications. And when Caleb reaches the conclusion Nathan wants (that Pollock would not have painted if he were too deliberate), Nathan congratulates him by saying, “See? There’s my guy. There’s my buddy who actually thinks before he opens his mouth.”33 Notice how this framing of the Pollock thought experiment contradicts the very conclusion Nathan derives from it. Apart from rehearsing a lecture or, say, mentally practicing an order at a restaurant, how often do we consider each word we will utter before speaking? And when, on those occasions, we start to think too intensely about what we are saying, would we not risk becoming too self-conscious (like Nathan’s Pollock), unable to make a single sound?

Nathan thus offers two seemingly contradictory accounts of consciousness: one automatic and seemingly naturalistically beholden, the other hyper-rational and apparently unemotional. For Nathan, a computer programmer, the human brain appears to operate as a computer running a consciousness program that one can activate as needed, turning it off to paint (“he let his mind go blank”) and turning it on to think (“engage intellect”). The default position of rationality, in his account, appears in the off position because most actions seem “automatic” (talking, breathing, painting). When partaking in philosophical inquiry (presumably a different kind of “talking”), one needs to “engage intellect” and thereby “think” before opening one’s mouth. Whereas a few paragraphs ago, I highlighted the impossibility of declaring, “I hereby decide to fall in love with you for the following reasons,” following this hyper-rationalist line of argument, it not only appears possible but is also empirically descriptive of how human interactions function.34

Yet Nathan’s rational action theory and his automatic theory of action appear in Ex Machina as two sides of the same coin. Even though Nathan’s Pollock turns off his mind before painting, and Davidson’s agents’ heads are full of action-causing reasons, both Nathan’s and Davidson’s accounts separate intention from bodily movements. “Intentions” (understood either as the accumulation of beliefs and desires or as programmed computer code) exist as a causal mechanism prompting agents/robots to move their bodies toward goals they would like to achieve. The world depicted in Ex Machina thereby appears as one wherein interactions appear fully explicable through game-theoretic models of payoff maximization, where agents calculate actions and feelings in response to their reasoned assessment of the motivations of others.35 In a climactic reveal, Nathan glibly tells Caleb that he has been lied to and is a pawn in Nathan’s meta-level test: “To escape, she’d have to use self-awareness, imagination, manipulation, sexuality, empathy, and she did. Now, if that isn’t true AI, what the fuck is?”36 For Nathan, an account of payoff maximization satisfies the modified Turing test because Ava rationally assessed her options and calculated her actions. If this degree of calculation does not provide evidence of consciousness, what the fuck would?

Ava’s Marks in the Age of Amazon

Although Caleb might not share Nathan’s view, when Ava shows him one of her drawings, he seems unable to consider it outside of a rational action-type paradigm. As Garland writes in the screenplay, Ava shows Caleb a piece of paper on which she has made “marks” that are “totally abstract. A mesh of tiny black marks, that swirl around the page like iron fillings in magnetic field patterns.”37 Garland’s use of the term “marks” is revealing because it highlights the relevant distinction Caleb must consider in this Turing test session: “the empty signifier” of marks and the meaningful use of intentional language and art.38 In a thought experiment developed in the essay “Against Theory,” Steven Knapp and Walter Benn Michaels argue that encountering a set of “marks” on sand caused by a wave is not the same as encountering language, even if the marks look identical to words.39 Transposing their “wave poem” thought experiment to Ex Machina, we can understand why Caleb must ask, “Are these marks mere accidents, produced by … mechanical operation,” either Nathan’s deterministic programming or the physical forces implied by “magnetic field patterns”?40 Or are they meaningful drawings because they were intentionally produced?

The wave poem’s implications are especially relevant to concerns in postmodern aesthetic philosophy, as the thought experiments developed by Arthur Danto throughout his career attest. Despite Toril Moi’s claim that Knapp and Michaels “produce an utterly peculiar argument,” Danto developed a practically identical thought experiment half a year after Knapp and Michaels’s essay with a nearly identical conclusion.41 “Imagine a sentence written down, and then a set of marks which looks just like the written sentence, but is simply a set of marks,” writes Danto.42 “The first set has a whole lot of properties the second set lacks,” including syntax and grammar, “And its causes will be quite distinct in kind from those which explain mere marks.”43 Although the sets are empirically identical, he argues, meaningful language used by speakers says something, whereas marks do not. Extrapolating from Danto, Knapp and Michaels’s conclusion, we could see how the question Caleb must ask about Ava’s marks/drawings is: “to interpret or not?”44

To get more data to answer such a question, Caleb asks Ava what the marks represent, to which Ava “disappointedly” responds, “I thought you would tell me. … I do drawings every day. But I never know what they’re of.”45 Although Ava has been programmed using a Google-like search engine named Blue Book, an allusion to Wittgenstein’s transition to his later philosophy, she appears unable to say, “It’s not a drawing of anything. It is an abstract work of art.” As readily available art dictionaries produced in the wake of artistic modernism state, “abstract art as a conscious aesthetic based on assumptions of self-sufficiency is a wholly modern phenomenon.”46 Non-figurative drawings can be found throughout history, yet art consciously produced as abstract art requires the historically emergent self-awareness of the very meaning of artistic production as such. “Abstraction,” as another art dictionary puts it, is not simply the “processes of abstracting from nature or from objects” but is rather the self-aware act of presenting “forms and colours that exist for their own sake.”47 In these definitions, the phrases “self-sufficiency” and “for their own sake” describe the intentional actions and social practices that enable the creation of art that embodies meaningful formal relations that do not point to the world via the representation of people or objects.

Apparently unable to consider the meaningfully autonomous, non-figurative nature of abstract art as a possibility generated by Ava, Caleb turns to what he can assess. He invites Ava to “try” to “sketch something specific … like an object or a person.”48 The drawing could be of “[w]hatever you want,” he tells her. “It’s your decision … I’m interested to see what you’ll choose.”49 While the marks made by Ava risk appearing irrational—something like randomly generated output—choices made within a set of constraints to produce a final product are explainable and thereby rational enough to pass the version of the Turing test Caleb is conducting. Like the picture theory of language Wittgenstein would come to reject, for Caleb, mimetic art appears to be more logical because it appears to him representationally connected to the world of rational choices.

The scene thus ironically depicts how Ava’s search engine does not provide readily available definitions. And even if it did, defining via ostension would not adequately provide proof of consciousness. Meaning and understanding, as Wittgenstein came to argue, are not the products of the algorithmic application of a rule nor the deictic formalism that connects meaning to the world via symbols. If Caleb understood Wittgenstein’s account of language as use—which Wittgenstein began to develop in the lectures that give Ex Machina’s search engine its name—he would recognize the limitation of a decontextualized question such as “Could a machine think?” (like the question “Can a machine have toothache?”) detached from the embedded social practices in which “thinking” occurs.50 Or, putting the point in Knapp and Michaels’s words, “the only real issue is whether computers are capable of intentions,” intentions defined not as the ideas in an agent’s head separated from the actions, language, and art they merely “cause” but as embodied within them.51

In the world of Ex Machina, though, the concept of intention appears to be negligible if not ultimately irrelevant. A robot like Ava is at least as conscious as Pollock, who empties his mind and merely allows his hand to move. In Garland’s extended version of the Pollock thought experiment, not included in the final cut of the film, Nathan suggests that a machine’s inability to know why it generates squiggles is comparable to Pollock’s blank mind. Here is Garland describing the omitted thought experiment in a badly copy-edited interview. (Note that the bracketed clarifications are inserted by the interviewer, except for the two I indicate as my own.)

Could a Pollock be recreated by someone else [a robot] and with different drips and different strokes, could that be as valid. And this gets into a conversation about conciseness [sic, my addition], that if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it’s a duck. So … [in the scene not in the final film] Nathan has done this multibillionaire guy experiment where he bought a Jackson Pollock for 60 million dollars and then he had it recreated using original canvas from the Pollock estate and had them recreated down to the microscopic level. And then he mixed them up and destroyed one of them, and he had no idea which was the original and which was the fake. So, what he’s saying to Kaleb [sic, my addition] is: does it matter which is the original and which is the “fake,” which is what they’re discussing with the robots.52

Nathan develops Danto’s “problem of indiscernible counterparts” by literalizing its experimental procedure.53 Like Danto, Nathan faces two identical objects that he cannot physically distinguish. Unlike Danto, Nathan does not invoke the institutionalist, contextualist claims about “the artworld,” nor does he invoke the artist’s intention.54 Instead, Nathan asks if the indistinguishable counterfeit could be considered as “valid” as the original, and the answer he advances is yes. The epistemological impossibility of distinguishing the counterfeit suggests the practical irrelevance of the ontological question, “Is it a work of art?” If it looks enough like a Pollock, it is sufficiently Pollock-like to pass. Nathan’s conclusion appears to contradict Danto, who draws from his thought experiment a conclusion closer to that of Knapp and Michaels’s account of intention. For Nathan, “validity” is so detached from something like an aura of originality that, in the unfilmed scene, he destroys one of the paintings, not knowing which is which. “In fact,” he tells Caleb, “I hope it’s the fake. It has all the aesthetic qualities of the original, and it’s more intellectually sound.”55 By unknowingly destroying the original, he would prove the point that the aura of originality is irrelevant, and a counterfeit is just as “valid.”

But with the invocation of “intellectual soundness,” Nathan raises a new issue: why would a fake be more “intellectually sound”? Perhaps because the logic of supply and demand provides reasons in a way that Nathan’s Pollock cannot. Within this thought experiment, we could imagine asking Ava, “Why did you create that object?” to which Ava could say, “Because Nathan requested it,” or “Because a buyer commissioned it.” It is as if Nathan orders a mechanically reproduced knockoff on Amazon that is rationally better than the original because the market provides a causal explanation for its production.

Garland’s thought experiment thus presents a fake “Pollock” that we should understand as produced within the conditions described by Mark McGurl as the “age of Amazon,” wherein “social relations” are “customer relations.”56 In this age, an artist is a content creator, the beholder is a customer, and the work of art is a commodity for sale. As William Deresiewicz similarly describes, these conditions exist within the “paradigm” of the content “Producer,” wherein the artist-as-producer creates “content” that vies, along with everything else, for attention within the market.57 For both McGurl and Deresiewicz, these conditions exist in the aftermath of a collapsed institutional “cultural boom” that had given rise to credentialed professionals who had (temporarily) operated outside of market valuation.58 The age of Amazon and the paradigm of the Producer both name the collapse of such spaces.59

Garland’s invocation of a Danto-like thought experiment is thus revealing because Danto is the paradigmatic philosopher of this collapse, which he narrates as the end of art history. Responding to the developments in Pop Art, Danto argued that the modernist one-upmanship of formal experimentation had exhausted itself.60 The linear, progressive narrative culminated in a dialectical synthesis that collapsed art into philosophy. With that collapse, “The boundary between vernacular and high art,” he argues, “was breached in the very early 1960s. It was a way of overcoming the gap between art and life.”61 Although Danto does not connect this “breaching” with the market subsumption of the spaces in which modernist formal experiment had flourished, we should detect in Danto’s account of Pop Art hints of the market logic that constitutes the breach.62 The ontological distinction between “art” and “life” had so dissolved that an artist such as Andy Warhol “shows a philosophical shift from the rejection of industrial society … to endorsement.”63 Insofar as Warhol “endorses” industrial society, the critical space potentially established by his art has so collapsed that the categorical difference between a work of art and a commodity no longer appears to obtain as a meaningful distinction.64 For Danto, Warhol “embodied a concept of life that embraced the values of an era that we are still living in.”65 Elsewhere, Danto names this “era” the “age of Brillo,” which, we could now say, ushers in the age of Amazon by exemplifying (or, in Danto’s words, “embracing” and “endorsing”) the intensifying market logic that undergirds them both.66