In 1862, a young critic, Théodore Duret, learned that two titans of contemporary painting, Camille Corot and Gustave Courbet, were visiting his hometown in Saintes. Rushing to meet them, he found the artists on the top of a nearby hill overlooking the commune. To his astonishment, the two had planted their easels side-by-side, “far enough away that they could not see each other’s work, but close enough so that they could exchange ideas and conversation.”1 Duret watched, awestruck, as they began to work. “They painted their views on little canvases of the same dimensions and agreed to stop working at the same time” (figs. 1 and 2).

Observing their process, Duret marveled at their commitment to painting what they saw. “When they painted before nature, they rendered its aspects without changing anything.”2 Seen together, the pair of paintings revealed something that neither could disclose on its own. “These two works, executed simultaneously by Courbet and Corot, can help us to recognize the common principles that they followed.” Individually, each painting might conceal some adjustment to the landscape, changes made to improve or prettify the world that it depicted. Together, they kept each other honest, for so long as they clung “as close as possible to the texture of the landscape that they had beneath their eyes,” then anything in one artist’s view should also appear in the other’s.3 Collaboration became corroboration as “they applied themselves to fixing with exactitude the things seen.”

Years later, both works that Duret had seen in progress happened to be listed in the same auction. When the critic came upon them, they transported him back to that summer’s day:

What struck me above all was the fidelity with which the aspect of the places was rendered. The steeples of the churches Saint-Pierre and Saint-Europe, so particular, were on the canvas in the exactitude of their form. The local vegetation, characterized by the leaves of the elms which naturally grow there had been seized in all their truth.

Based on this celebration of “fidelity” and “exactitude,” one might expect the two paintings to be near-identical, to differ only in ways commensurate with the small distance between the artists’ easels. Duret was surprised to find, however, that “the two paintings [also] revealed the individual manner belonging to both artists, more tender in the Corot, more severe in the Courbet.” Somehow the artists both painted exactly what they saw and revealed themselves as individuals.

Because they possessed an enlarged sensibility, such that they vibrated before nature and experienced emotion in contemplating the scene, that sentiment worked its way into the paintings that they painted. It constituted them as works of art. It became one with them and animated them, not as an added ingredient or due to reflection, but as an intrinsic part of the execution, without the artists even realizing it.4

Watching the two artists work helped Duret to see this unexpected synthesis of apparent opposites, impersonal exactitude and personal temperament.

As he tried to explain how this fusion was possible, his analysis burst like buckshot with essential but enigmatic terms, “sensibility” and “sentiment” versus “fidelity” and “exactitude,” oppositions that were crucial to the art theory of his time. At their root was the enigmatic distinction between subjective perception and objective reality, which, to Duret, the practice of painting side-by-side uniquely rendered visible. When the critic sat on that hill in Saintes, these terms were still unsettled, not having fully filtered down from philosophers and Germanophiles into everyday use.5 And while he did not use them when recounting the meeting of Corot and Courbet, we will see that the tale gives them an ostensive definition: subjectivity means whatever it is that causes two artists painting the same scene to see it differently.

In this respect, Duret’s story typifies what I shall call the parable of the painters: imagine two artists, each copying exactly what he sees, only to find that their works look different. As early as 1818, a treatise on landscape asserted that many artists’ paintings of the same viewpoint would differ according to “the diversity of their organs and their sensations.”6 By 1873, one critic prefaced his use of the heuristic—“place ten artists before the same landscape”—by acknowledging that “the following argument has been somewhat overused.”7 It became so firmly entrenched that it entered the highly codified realm of standardized testing, as in a 1902 textbook for the baccalaureate in philosophy, which prompted students to prove that “the faithful imitation of nature is impossible” by imagining two artists painting the same landscape.8

Ultimately, the parable became nothing less than an origin story for art history as an academic discipline, recited in the famous opening paragraph of Heinrich Wölfflin’s urtext, Principles of Art History (1915). There, when four artists noticed how differently they rendered a scene painted side by side, they discovered comparison as an art historical method—becoming distant ancestors of all students who learn to look at artworks in a classroom, where our teachers project two slides and compare them.9 But, to Wölfflin, those four artists revealed not only style but subjectivity, realizing in a flash that “there is no such thing as objective vision.” Likewise, when E. H. Gombrich retold the same story in Art and Illusion, he characterized its import as picturing “the limits of objectivity.”10 With these phrases, they stated plainly the lesson the parable had always taught: that when multiple artists paint the same thing, each trying his hardest to reproduce exactly what he saw, they end up with different paintings because they saw the same thing differently.

By the time it reached Wölfflin, however, the parable had spread far beyond its initial use in art theory, deployed formulaically whenever an author needed to explain the limits of objectivity. Here, for example, is how Gustave Le Bon argued that no historian can impartially recount events:

The historian sees events like the painter sees a landscape …. Many artists, placed before the same landscape, will necessarily translate it each in his own fashion …. Each reproduction will thus be a personal work, that is to say, interpreted by a certain form of sensibility. It is the same for the writer. One can thus no more speak of the impartiality of a historian than that of a painter.11

Le Bon thus used the tale to assert a fundamental principle: the unavoidable subjectivity of social science. He saw it as proof that there is no such thing as objective representation. A work of history, like a painting, always has a style.12

A text search using Gallica (the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France) produces many more such examples.13 The parable became a pedagogical staple, repeated in textbooks on prose composition, intellectual property, and jurisprudence.14 Authors employed it whenever they wanted to explain how different people can experience the same thing differently. How could many citizens have conflicting views of the July Revolution?15 Why do multiple sommeliers give contrasting descriptions of the same wine?16 What explains the diverse worldviews of African tribes?17 Why do the four Gospels disagree on basic points?18 How can two actors interpret Hamlet nearly antithetically?19 Well, imagine two painters painting the same landscape.

As the parable migrated from art criticism to the wider world, its purpose changed. Initially, it was used to understand artistic style, especially to shift the register of explanation from manual causes (the way a painter holds his brush, the materials he chooses, etc.) to cognitive ones (the way he sees and understands the world). With repeated retellings, however, cause and effect flipped. Instead of proving that style is subjective, the parable seemed to reveal that subjectivity is stylistic.

Here, then, is our agenda: to trace how a question about style became a theory of subjectivity. In so doing, I do not seek to endorse that theory—to say that we should see subjective experience as a style of mindedness. Nor am I willing to concede its central inference—that if different artists represent the world differently, it must mean that they see it differently. On the contrary, the parable interests me precisely because it offers an image of subjectivity that is lucid enough to criticize, concrete enough to dispute.20 That clarity follows from the scenario’s roots in historically specific image-making practices. While most individual recitals invent hypothetical artists as stripped-down heuristics—in Wölfflin’s and Gombrich’s citations of Richter’s tale, for instance, the actual artworks required no specific comment—the story presupposed and challenged definite developments in artistic practice.21 To tell it in abstract thus means missing its true significance, which emerges only when we assay these theories in the fire of practice.

That practice: artists painting side by side. Long a staple of art school training, wherein rows of students all copied the same model as they learned to draw and paint (fig. 3), side-by-side painting became its own genre in the early nineteenth century, especially in France, prompted and enabled by wider, more familiar developments in the history of French painting. At that point, an emergent realist paradigm overturned existing conventions of landscape as an art. Painters began committing, at least rhetorically, not to modify or arrange the objects of their vision but rather to copy them exactly as they appear. As the century progressed, this mode gave rise to another variant, impressionism, which emphasized the word “appear.” The impressionists attended to the specific cognitive and physiological form of perception, and, in the process, highlighted the subjectivity already involved in the reception of realist painting. These movements joined another incipient challenge to dominant theoretical and practical paradigms: photography. If the realists and impressionists promised to render what they saw without intervention, photographers claimed this neutrality as an automatic feature of their process. Together, these developments prompted a major reassessment of the epistemological premises at stake in representation.

This essay thus traces the somersaulting feedback between the theoretical possibilities and historical reality of painters painting the same thing, tracking critical recitals and selected painted examples. While the parable proved useful beyond nineteenth-century France—Wölfflin’s source, Richter, is especially interesting—I concentrate on this period as a uniquely fertile ground thanks to its singular combination of institutional factors: first, its prominent insurgent artistic movements (realism and impressionism) and, second, well-developed, robust institutions of criticism that encouraged real-time engagement with contemporary developments.22 This history involves close attention to small variations in the evolving recitals of this parable, sources that, in their obscurity, might appear of interest only to specialists in nineteenth-century French art and theory. For that reason, I begin with a later retelling of Wölfflin’s example, one that shows how my arguments bear on key debates in the history of knowledge.23

Styles of Painting, Styles of Knowing

To explain why scientific reasoning does not exhaust genuine knowledge, Ernst Cassirer reached for the parable. Science, the philosopher explained in 1944, searches for objective principles from which we may derive all particular phenomena—e.g., once a chemist knows how many protons occupy an atom’s nucleus, “he may deduce all the characteristic properties of the element.”24 Art, by contrast, refuses deductive reasoning. Just the opposite, whereas science seeks to uncover the objective laws governing reality, art celebrates the proliferation of subjective experience.

To argue this point, Cassirer repeats Wölfflin’s story and quotes the latter’s conclusion that there is no such thing as objective vision. Insofar as their works differed, Richter and his friends demonstrated the world’s resistance to exhaustive objective description. Rather, they showed how visual experience constitutes its own kind of knowledge, subjective but no less real than scientific reasoning. And so, as Cassirer writes elsewhere, “to the extent that we can have knowledge through visible and tangible forms … style is rooted in the deepest foundations of knowledge.”25

With such claims, Cassirer helped inaugurate an enduring problematic in the history of knowledge, which has come to be called “styles of reasoning.”26 This term refers, as Arnold Davidson explains, to “the conditions under which various kinds of statements come to be comprehensible.”27 Building on this definition, Ian Hacking notes that styles of reasoning help us understand what we mean by objectivity, “not because styles are objective (i.e., we have found the best impartial ways to get at the truth), but because they have settled what it is to be objective.”28 He thus compares styles of reasoning to Kant’s transcendental categories as means of explaining “how objectivity is possible … preconditions for the string of sensations to become objective experience.” For Kant, categories like causality cannot be established in experience (as though there was some raw consciousness to which cause could be added) but are rather conditions for us to experience anything at all. Likewise, styles of reasoning are not more or less objective but instead explain “how objectivity is possible … [They are] preconditions for the string of sensations to become objective experience.”

Whereas subjective experience evidently differs among individuals, societies, and historical periods, objectivity seems, by its own definition, universal and constant. This intuition, however, belies a complex history whereby the criteria for objectivity—ascribed variously to claims, beliefs, and institutions—have changed over time.29 If the meanings and uses of “objectivity” vary among communities, then the concept itself cannot be objective in the usual sense. Thus, writes Steven Shapin, “that which seems to be transparently about objects in the world contains ineradicable elements belonging to subjects, their background knowledge, their categories, customs, conventions, and purposes. Our scientific knowledge is about the world and it is also irremediably about us, as knowers. And the condition of our knowledge being intelligibly about the world is that it contains a bit of us.”30

In the most comprehensive history of objectivity, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have traced the concept through a series of what they call “images” (O). This word functions both figuratively and literally. Literally, it means varieties of pictures used to obtain and disseminate objective knowledge (medical illustrations, photographs, etc.). Figuratively, it means the varying conceptions of objectivity that these pictures enable us to differentiate and classify (truth-to-nature, mechanical, etc.). The authors’ aim is not to assess whether a diagram or an x-ray are really objective images but rather to elucidate how the conceptual differences between those practices enable reflection on the conceptual history of objectivity. “[These] specific forms of image-making sculpt and steady particular, historical forms of the scientific self,” such that we can delineate styles of objectivity by attending to histories of image-making practices (O, 4).31

So far so good. Yet once we accept this argument, we can all too easily fall into the trap, treating subjectivity as what Shapin calls the “evil twin” of objectivity, “the bin that holds the heterogeneous bits and pieces of whatever it is that makes trouble for objectivity-stories.”32 If one misreads histories like Daston and Galison’s in this way, one can easily end up universalizing subjectivity instead: “If we no longer believe in the objectivity of legend, that puts quite a load on the subjective items we use for deflationary purposes: oddly, it seems here that objectivity doesn’t exist, but subjectivity does.”33 It thus becomes necessary to take the analytic paradigm that Daston and Galison applied to objectivity and return to its complement, to look for images that would particularize our understanding of subjectivity.

That brings us back to the parable of the artists. This “image” too has both literal and figurative meanings. There are real, historical instances of artists painting the same thing differently, and there is the image envisaged in the parable, in which we are asked to picture not any one landscape but the artists painting it together.34 The viability of the latter does not hinge on whether a given pair of paintings (by Corot, Monet, Cézanne, etc.) really picture subjectivity—they do not, at least, not in the straightforward way presumed in the parable. Rather, the parable discloses what is meant by subjectivity, elucidating how the concept found its historically determinate explanation as what gives experience its style.

In everyday parlance, we commonly use the word “style” with reference both to individuals (“the style of Monet”) and groups (“the impressionist style”). To that end, Wölfflin noted that, however much the artists in his opening parable differed from one another, “we should probably find the four Tivoli landscapes rather similar, of the [Nazarene] type.”35 This claim matters immensely, for as Todd Cronan writes, “if for Richter the point of the episode was to show the depth to which personality runs in a painter’s practice, then for Wölfflin the point was to show the opposite: that an artist carries a ‘mode of perception’—something definitely not personal—with him wherever he goes.”36 Meanwhile, Davidson explains the priority of collective style in disciplinary terms, as a shift from art history’s “perception and vision” to epistemology’s “reasoning and argumentation,” which, however particular a given author’s way of writing, entail conceptual frameworks dependent on social agreement.37

To that end, Hacking explains his preference for the phrase “styles of reasoning” over the commonly used “styles of thinking”: “Thinking is too much in the head for my liking. Reasoning is done in public as well as in private: by thinking, yes, but also by talking and arguing and showing.”38 For that reason, Daston and Galison mostly avoid the word “style,” which they worry implies a mistaken view of epistemic virtues as merely individual, whereas, in fact, “they are never merely idiosyncratic, one personal style clashing with another. There are no purely private values, any more than there are purely private languages” (O, 367).

These concerns indicate something of real importance to the conceptual history that I document below: namely, a deep connection between style and skepticism. If artistic styles—or, even worse, styles of reasoning—could be completely idiosyncratic (i.e., akin to a private language), then there would be no way to reconcile individual subjectivities or test perceptions against reality. I believe, however, that this skeptical conclusion does not follow from the image of subjectivity given by the parable. On the contrary, this image works precisely to make subjectivity publicly available.39 As Richard Neer argues, we use the concept of style to establish criteria of likeness, to identify respects in which one visual object is like or unlike another. And criteria must be explicable: “If there is no private language, there is no private style.”40

To that end, the parable’s usefulness lies precisely as a heuristic for rendering experience public, a way of picturing subjectivity as a mix of difference and sameness. As an image of subjectivity, grounded in and responsive to a concrete image-making practice, the parable thus uniquely fulfills the promise of style as (what Neer calls) a means of testing “the extent to which we, today, do or do not share criteria of judgment, do or do not participate in a shared grammar of concepts, do or do not live a common form of life.”41 To paint the same thing, and to compare those paintings, is to visualize not only that we see the same thing differently but also that what we see differently is indeed the same thing.

Three Poets, Three Painters, a Surveyor, and a Photographer

The first edition of the Larousse dictionary (1869) explained that an artist’s style derives from his singular way of seeing the world. “Each artist … has his own manner of envisaging nature which is absolutely unique to him, so much so that ten artists reproducing the same scene, the same figure, the same site, will produce ten quite dissimilar works.”42 To elaborate on this idea, Larousse quoted a long passage from an art critic named Edmond About, who in 1855 explained the concept of style with the following parable.43

One day, a surveyor tasked with inspecting a forest brought along Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Alfred de Musset. In the afternoon, the four men split up and each wandered the forest alone. Hugo envisioned trunks stretching up toward the infinite. Lamartine saw tragedy, of beings that grow so close together but cannot reach out to touch one another. Musset felt life’s sweetness in nature’s limitless bounty. But the surveyor saw merely such-and-such number of so-and-so specimens of trees. In the evening, the men returned to their camp and discussed their experiences, each “painting” a verbal image of what he had seen. They gasped at Hugo, cried with Lamartine, and smiled with Musset. Only when the surveyor gave his report did they realize that the places each had described so differently were all one and the same.

A few days later, painters Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau went into the same forest with an unnamed photographer. In the afternoon, the three men split up and each wandered alone. In the evening, they returned to their camp and compared their works. Corot had painted a gray and misty part of the forest, Rousseau one dense and overgrown. But “the photographic plate, drawn by the sun itself, was exact to a bit of grass nearby.”

While the surveyor composed his report with “irreproachable exactitude,” any competent colleague would have done the same. And while the photographer produced an excellent photograph, any other photographer would have obtained the same result, for “neither the inspector nor the photographer were men of style.” By contrast, the works by the poets and painters were each unique because they “painted the forest, not as it is but as they saw it.”

From this example, About arrived at his definition: “Style is the transformation of things by the mind of man.”44 In this account, a painter’s style does not come merely from the way he holds his hand—it is not, About wrote, “orthography”— but from his unique way of seeing the world.45 Paintings (both visual and poetic) exhibit personal style because perception is stylistic. The visible divergence among the artists’ representations of the same forest therefore illustrated how the objective world splits into subjective experiences.

For now, however, let us bracket the issues of poetry and photography to focus only on the painters. It was, of course, no accident that of all the artists active in 1855, About chose to name these, for Corot and Rousseau epitomized the new mode in landscape called “realism.” As About ventriloquized their principle: “We faithfully copy the objects that chance has put before our eyes; we abstain from any composition; we refuse to adjust a tree or a mountain.”46 As a reward for this fidelity, “nature knows [Corot] and loves him, speaks in his ear and tells him her secrets.”47

If About had instead more conventional artists, the lesson of his parable would not have made sense. It was premised on the idea that, when artists paint a landscape, they are attempting to copy exactly what they see. Yet this assumption was hardly universal. Consider, for instance, a sketch by Corot’s teacher, Achille-Etna Michallon (fig. 4). In the early 1820s, he toured Italy with a friend, the Swiss genre painter Léopold Robert. In Naples, they visited a prison where they met a notorious brigand, whom they painted side by side (fig. 5). Neither artist intended these views to be seen as artworks. Rather, they were preparatory studies for larger compositions. Thus, Robert inserted his bandit into a genre scene with another folkish figure, whereas Michallon miniaturized his, placing him in the midst of an imaginary landscape (figs. 6 and 7).

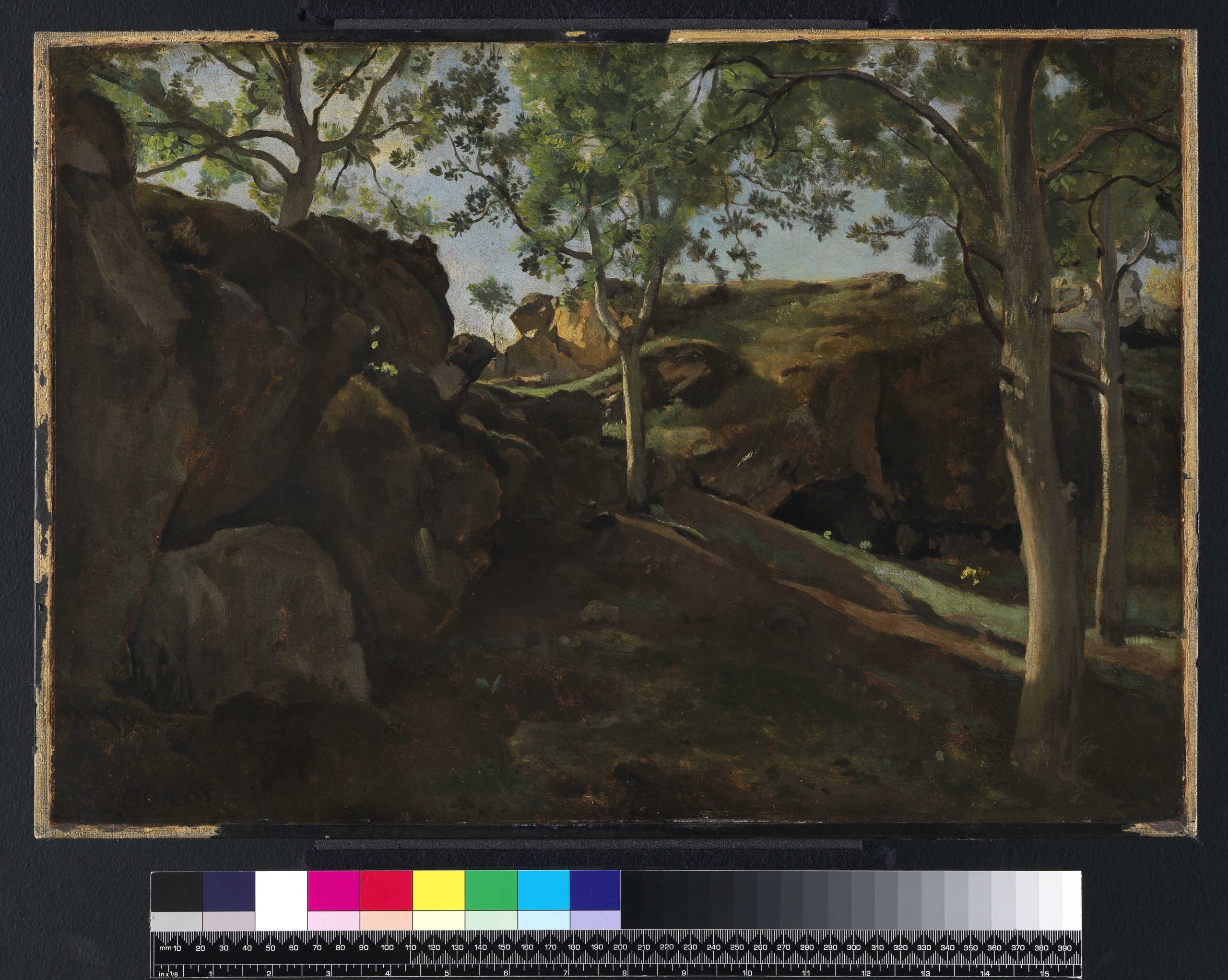

Compare these works with a later pair by Michallon and Corot (figs. 8 and 9). These do not obviously present one or two motifs memorialized for insertion into subsequent works. Rather, each of the equivalently sized sketches seems specifically concerned with establishing compositional unity between edges and center.48 Michallon’s solution was to bracket both edges with boulders, which, together with the canopy of foliage at top, act as repoussoirs—depicted objects that recapitulate the frame to confine our attention within its limits. A strong vertical highlight on the middle tree directs focus to the center of the scene, while the alternating light and dark faces of the midground ridge enhance our sense of space. To achieve the same balance from his own position (forward and to the left of his teacher), Corot needed a different solution. He centered his view on a forking trunk, pushing the other two trees to the framing position at the right edge of his painting. Instead of Michallon’s contrasting planes of light and dark, he stabilized his space with a strongly X-shaped composition that anchors our view of the whole. These differences, however, only secure the works’ overall similarity, with each artist pursuing the same end—a balanced, self-contained composition—from his own vantage point.

These examples indicate why the parable flourished in nineteenth-century France, thanks to its unique mix of practical and theoretical developments. The story must begin with artists resolving to copy exactly what they see, a scenario made more plausible and vivid given familiarity with actual realist painting. But for the payoff to work, the differences among the artists’ depictions of the same scenes must not have a merely manual etiology—after all, Corot and his ilk did not invent this kind of putatively exacting realism. Rather, the story finds its significance once that practice collides with emergent ways of understanding perception and knowledge. These theoretical efforts necessitated specialized concepts, terms that began in rarified intellectual culture but gradually shaped the way everyday people came to understand their experience: subjectivity and objectivity.

In one of the earliest efforts to define these words for French readers, influential theorist Germaine de Staël invoked the Kantian distinction between “the forms of our understanding” and the “objects that we understand according to those forms.”49 There are categories such as causality (this causes that), modality (this is possible), and quantity (these are several different things) that we never experience in themselves but which give form to our experience writ large. Thus, “we can perceive nothing except via the immutable laws of our manner of reasoning.” Notably, those forms do not vary among individuals. On the contrary, the laws of cognition count as laws only because they hold universally. And yet, in the parable, the artists do not discover subjective styles in the gap between painting and reality. That is, the artists do not have their realization exclusively by comparing their works to the world. To do so would be impossible, for they could never escape their subjective perception to judge the relation. Rather, they discover it in the differences between one painting and another, through which they can assess the particularity of how each sees the common view.50

We can thus disambiguate two senses of the subjective/objective opposition. First, the division of mind and world, perceiver and perceived. Second, variations among minds, such that we call “subjective” what differs for different people, “objective” what must hold true for everyone.51 In this latter sense, objectivity really amounts to what Hacking calls a “super-duper obligatory intersubjectivity.”52 A claim is objective if it compels everyone to assent to it. Subjective experience is personal and variable, objective reality impersonal and universal.

In the parable, however, the two senses merge, fusing the oppositions of perception/reality and personal/impersonal into one master distinction. For instance, we find About confounding them when he sought to define the terms in 1865:

The Germans, in their metaphysical jargon, have identified the abyss that separates the objective from the subjective …. A twenty-kilo weight always weighs the same amount in itself, from an objective point of view, which is to say that the object weighs twenty kilos. But according to the subject who carries it, it weighs a hundred thousand pounds or none at all it. For the mouse … it is as heavy as the Himalayas. For an elephant, it’s a mere feather. Voila, the subjective point of view.53

Here, the difference between reality (what the weight weighs “in itself”) and its perception becomes one between the perceivers (elephant, mouse) who perceive it differently. Given this reasoning, it is not clear what an objective depiction would look like. For any painting would always implicate the artist’s point of view, not only as a human perceiver but also as one perceiver among many. This puzzle established, let us return to a key player in About’s hypothetical, one whose role in the story would only grow: the photographer.

Ten Glass Eyes

In 1857, the realist critic Champfleury exhorted artists to copy nature exactly as it is. In pronouncing this aim, however, he expected the reader to retort, “A daguerreotype does the same, it’s a machine. So you want to make the painter into a machine.”54 He rebutted this imagined interlocutor, saying, “The reproduction of nature by a man is never a reproduction or an imitation, it will always be an interpretation,” and proposed to “make [his] thought clear with the following facts.”

Ten daguerreotypists come together in the country and submit nature to the forces of light. Beside them, ten students of painting copy exactly the same site. The chemical process completed, the ten plates are compared. They render exactly the same landscape with no variation between them. By contrast, after two or three hours of work, the ten students (even if they are all under the direction of the same master, who taught them well or badly) put their sketches one next to another. Not a one looks alike …. It is thus easy to affirm that man, not being a machine, cannot render objects mechanically.55

Whereas the artists “copy” the landscape, the photographers merely “submit” it to the “forces of light.” By making nature the agent of its own representation, Champfleury made the ten human operators irrelevant.56 For while they encountered the landscape only indirectly, mediated by their potentially distorting perception, the machine allowed nature to show itself directly as it is.

This conception of photography typifies the mode of objectivity that Daston and Galison have labeled “mechanical” (O, 125–38). This ideal furnished an alternative to a previously dominant one, “truth-to-nature,” according to which we achieve objectivity by abstracting away the particularities of any given object to determine the genus it instances. A medical textbook, for instance, should not illustrate the liver with an exact depiction of any one person’s, which might be idiosyncratically large or small, healthy or unhealthy. Rather, it should distill the organ to its essence by stripping away everything particular, depicting not a liver but the liver. In the mid-nineteenth century, this image of objectivity as “truth-to-nature” competed with an alternate image, one defined by “the insistent drive to repress the willful intervention of the artist-author, and to put in its stead a set of procedures that would, as it were, move nature to the page through a strict protocol, if not automatically” (O, 121).

For example, in 1869, scientist Louis Figuier recommended that scientists stop hiring illustrators and start taking photographs. He explained that, despite the intense care that illustrators took in reproducing natural phenomena, their pictures were always “incomplete and unfaithful.” The illustrator could never achieve a complete “abnegation of his own judgment” but inevitably “replaces what nature presents to him with what he himself sees or what he thinks he sees.”57 Because each scientist-illustrator brought his own “theoretical predilections” to his object, he would involuntarily shut his eyes to anything contradicting his biases, such that multiple illustrators—each with his own preconceptions—would depict the same object differently. Whereas textbook illustrators worried about overabundant details distracting from the essential point, photographer-scientists embraced the new medium precisely because it dispensed with prejudicial presuppositions about what was or was not essential.

This conception of mechanical objectivity lay behind photography’s apparently direct access to nature. At first, we may suppose that we can measure the technology’s objectivity by the degree to which photographs resemble the objects they represent, however complex those objects may be, such that we can compare even the smallest detail between the picture and pictured object. In a speech announcing Daguerre’s invention to the Academy of Sciences in 1839, François Arago gave a telling example. While it would take legions of draftsmen decades of effort to transcribe a wall of hieroglyphs in Thebes, a single photographer could capture it with total exactitude in a single exposure. In this example, a viewer could in principle take this photograph back to Thebes and check its accuracy against the actual wall.58 Free from the tics and mannerisms of human bodies, such complicated renderings allow us to compare them point-for-point with what they represent.

Yet in the same speech, Arago also proposed potential objects for photography that intrinsically could not be compared to the real thing, objects both too large (celestial bodies) and too small (microscopic organisms) to be seen without technological aid. In these latter instances, photography did not confirm ordinary vision but rather extended it to things otherwise beyond its reach.59 The putative objectivity that photography afforded could not be seen by comparing representation to represented objects but by comparing multiple representations to one another (figs. 10 and 11).

This principle underlies Champfleury’s use of the parable: “Wherever ten daguerreotypes are leveled at the same object, the ten glass eyes of the machine will render ten times the same object without the slightest variation of form or coloration.”60 His account of photographic sameness presupposes the inherent diversity of painting. Whereas paintings represent the same thing in different ways, varying according to the temperaments of their makers, photographs represent the same thing in the same way. It is therefore not the surfeit of detail within an image so much as the constancy between them that makes photographs more objective than paintings.

It should be said that this argument was based on a fundamentally erroneous understanding of how photography works.61 The process was not really automatic but rather required trained judgment and manual intervention at every step—from the preparation of plates to their exposure and development. After all, John Tresch has shown that some of the earliest discussions of photography emphasized “not transparency but transmutation,” using the language of “activity, transformation, and even vitality.”62 That the non-interventionist reception ultimately won out supports Daston and Galison’s insistence that photography did not cause objectivity to be conceived as mechanical but rather became paradigmatic precisely because that conception already had root (O, 138–39).

Opposing this notional opposition between the objectivity of mechanism and subjectivity of art, working photographers countered by emphasizing the discernment and skill that distinguished one cameraman from another—arguing, effectively, that they have personal styles. In 1862, for example, European photographers were outraged when the Universal Exhibition in London classed their work with machinery rather than fine arts. Writing in solidarity with their English counterparts, the Société française de photographie accused the commissioners of having made a “philosophical” error:

Photographic works, at least those that have been produced by authors possessed of artistic sentiment, are not mechanical products. In effect, two artists, with the same apparatus, in the same conditions, could render the same portrait, the same view, not only in a very different manner, but each according to his own sentiment.63

The photographic society thereby appropriated the language of sentiment from the fine arts, where it referred to subjective aspects of perception.

Remarkably, the same argument appeared in Figuier’s discussion of artistic photography:

Have different operators reproduce the same natural site; ask different artists for portraits of the same person. Despite representing an identical model, none of the works will resemble the others. In each of them, you will recognize the manner or sentiment of the man who took it.64

Whereas he claimed, as quoted above, that a scientist should use photography to free his images from theoretical biases, he also held that an artist could use it to express “his individuality, his proper manner, the sentiment which distinguishes and animates him …. Instead of seeing it as a simple mechanism, we must then strive to push it even more in an artistic direction.”65 The relative objectivity of the new technology was therefore not inherent to the medium but rather a function of its use. When used scientifically, photographs were styleless and objective. When used artistically, they were stylistic, perhaps even subjective.

Style, Ideally

Recall the context of Champfleury’s argument, his defense of artistic realism against those who would accuse him of mechanizing man. He might have imagined his interlocutor as Charles Dollfus, whose attack on realism had been published the prior year: “Realism is mechanism; you are nothing more than better or worse instruments, destined to be dethroned from the day that the photographic plate condemned you without appeal. Art usurped by chemistry!”66 Surprisingly, he proved his point with the same parable that Champfleury would also use: “Place two of these so-called realists before the same landscape and have them paint it. Compare: the paintings are different. Realism is just a word. In fact, in an absolute sense, it will never exist.”67 From this scenario he concluded that “Even if the artist strives to be a copyist, he puts something of himself into the works that he claimed simply to transcribe. The artist never copies; he translates.”68

Thus, Dollfus and Champfleury used the same example to make opposite claims. To Dollfus, the inevitable differences between the two realists’ paintings showed the futility of their efforts, which fundamentally misunderstood the nature of art. He argued that realism is silly because, as the parable proves, mechanical realism cannot exist. Champfleury replied: exactly right, therefore artists can copy nature rigorously, resting safe in the surety that whatever they painted would include some irreducibly personal element. As Dollfus would have it, “We can never reach the ideal without going through reality, nor reality without traversing the ideal.”69

When the critic used the word, “ideal,” he did not mean the superlative beauty that conservative artists sought by lengthening a stubby leg or straightening a crooked nose until the body incarnated perfect beauty. Rather, Dollfus understood the word in its contemporary, philosophical sense. As cofounder of the Revue Germanique, which offered popularized summaries of post-Kantian texts in France, he used “ideal” to mean the subjective form of experience, distinguishing the world as it is in itself (real) from the world as we perceive it (ideal).70 The term so defined, the world comes to the artist already idealized, for it is always encountered through the matrix of experience. He therefore concluded that “realism is impossible, as is idealism,” because “an artwork forcibly and indivisibly requires both at once, for it is the idea materialized and matter idealized.”71

These arguments were developed in greater detail by Ludwig Pfau, a German intellectual living in Paris. In his treatise on aesthetics, Pfau explained that visual sensations give us only partial access to reality (only in sight, not taste; only the side facing my eyes, etc.) because we experience the world only as images. “The brain, in seizing the image [from the eye], subjects it to a second transformation.”72 This formulation seems to give cognition a two-part chronology. First, the eye sees, then the mind understands. But, for Pfau, such a separation could exist only in theory, belonging to the grammar of explanation not the nature of cognition. In actual experience, “there is no sentiment without the assistance of thought, no thought without the aid of sentiment.”73 The philosopher thus recapitulated Immanuel Kant’s famous dictum, “Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.”74 In other words, no one ever experiences sense data prior to conceptual understanding, the real prior to the ideal. The proof: “You have only to ask multiple artists to give a faithful reproduction of the same model and you will see, by the ideal difference between their copies, how the perception of the man transforms the objects without his volition and without his knowledge.”75

At this point, we begin to witness a significant change in how the parable functioned. In all the recitals rehearsed thus far (About, Champfleury, Dollfus, etc.), the tale was used to argue a position on artistic style, to show that all painting is necessarily subjective. Their aims were local to specific developments in contemporary art, prompted by the twin mysteries of realism and photography. Pfau, on the other hand, used the same parable not to explain style as a consequence of subjectivity but rather to cast subjectivity as itself a form of style.

Do You See What I See?

With the spread of popularized philosophy, mid-nineteenth-century critics mostly accepted the principle that we can access reality only as transformed by our perception. But these critics did not generally adopt the philosophers’ more complicated arguments for how that transformation occurs. Instead, they explained the mechanism of perceptual variability via empirical psychology and physiology, preoccupations that swept diverse fields in mid-nineteenth-century European thought.76 To understand the grounds of perception, scientists focused on optical quirks like afterimages and blind spots. Because these visual phenomena were non-veridical, having no corollary in the outside world, they came to stand for the “subjective” component of perception.77

For instance, one treatise on aesthetics attributed the differences between artists to what it called the “organizations” of their sensoria. “Just as we divide temperaments into sanguine, bilious, or lymphatic by virtue of the principle which dominates the composition of their blood, so I will divide the organizations by virtue of the general manner in which sensations are affected.”78 Sensations, the author explained, occur when a body receives a “shock” to its nervous system, which he compared to the striking of a tuning fork. In the analogy, this shock produces a note that is particular to each individual, around which the entire scale of perception is organized. After all, “the same landscape, painted from nature at the same time by many equally gifted painters will appear in many different aspects.”79

This text, while idiosyncratic, typifies key elements of its intellectual milieu. Compare a contemporary textbook on anatomy, which purported to demonstrate how disparities in retinal structure affect color perception with the same parable:

Watch two painters reproduce the same landscape. They could have the same facility with color … but yellow dominates the work of the first and gives it a warm tone; blue, on the contrary, is the general tone of the second and gives it a colder but more poetic aspect.80

This recital draws on a longstanding idea that color is essentially subjective.81 Whereas (primary) qualities like extension belong to objects themselves, (secondary) qualities like color belong only to the perceiving subject.

As proof of this subject-dependence, the textbook invokes the theory of color contrasts, soon to become an essential reference for avant-garde painters.82 “Each color, taken in isolation, has an absolute value. But if it is set beside other colors, it will have only a relative value. For white to remain white, it needs a touch of blue, green, or yellow, etc.”83 In other words, “white” does not describe an objective phenomenon, inherent in all white things, but a bundle of context-dependent sense data as physiologically perceived. As a result, the author added a further quirk to his recital of the parable: “One remarks a perfect harmony among the tones that cover [each] canvas, even though the colors they use are not the same.”84 In other words, though each artist sees colors in a unique way according to his temperament, the color relations within each work come together in a unified way.

Written in 1851, this text seems to anticipate a key feature of impressionist rhetoric—the idea that artists rendered the colors not of things themselves, but of things perceived at a given moment.85 For instance, if we look at a pair of works painted by Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir in 1874, we seem to find its hypothetical realized in practice (figs. 12 and 13). They picture a docked boat in the foreground, its sail reflected in the water below. Both show the far bank in the background, lined with trees bounded at the rightmost edge by a cluster of buildings. Certain details suggest that some time has elapsed between Renoir’s and Monet’s chosen moments. One figure has moved from the plank to the boat, and the two boats at the left edge of Renoir’s seem to have drifted beyond the frame. These discrepancies focalize a gap between the depicted instant and the time required to paint it.86 Yet they also work to secure the moments’ proximity to one another. By enumerating the slight changes to the scene, the artists indicated how little time really passed—just enough for this man to move there—especially given that the depicted shadows retain the same angle.

We find a more critical difference, however, between the artists’ palettes. Monet used a more saturated blue for the river and sky and a cooler white for the canvas sails. His colors are bold throughout the painted surface, whereas Renoir’s seem to diffuse from the center out. Were one to cut a comparable fragment out of either—say, the green foliage at the bottom-right corner—and use it like a color sample, one would immediately notice the contrast between them. But when the works are taken as wholes, the parts offset one another, exhibiting something akin to that “harmony among the tones” posited in the textbook parable. Renoir’s blues are cooler because his whites are warmer, all diffused within his gauzy facture. Look at the rowing shells at midground right in Monet’s view, bold swipes of red made all the bolder by the contrasting green water and impasto white rowers. Compare Renoir’s take on the same motif, much less readily perceptible. He dragged his hull (one, not two) into the reflected creams of the sailboat above, its desaturated orange bridging the chromatic difference from the surrounding vanillas (fig. 14). Taken as whole paintings, set one beside the other, these works seem to imagine what it would be like for various temperaments to transform a common scene by modulating its constitutive colors. The discrepancies between the artists’ palettes are thus taken to evince stylistic features of their subjective perception.

In rehearsing this interpretation, I am not suggesting that we use the artists’ choices of colors to infer differences between how they perceived the same scene, as contemporary critics did. Again, paintings do not straightforwardly materialize subjective perception any more than photographs register objective reality. Rather, we should see the two artists’ palettes and handling as rhetorical means of marking their vision as subjective—in keeping with the larger rhetoric of impressionism. That is, because the artists’ colors differ while each realizes a whole unified within each individual’s perception, the works visualize what it would be like to have styles of subjectivity.

However, when artists like Monet used color to convey the subjectivity of their vision, they armed their opponents with a powerful weapon. On the one hand, their sympathizers sought to characterize their chromatic capaciousness as a radical form of perceptual realism. Jules Laforgue, for instance, sought to detail the “physiological origins of impressionism,” based on the premise that, “in the whole world, there are not two identical eyes.”87 Corot expressed a similar idea when he aphoristically declared to Pissarro, “We don’t see things in the same way. You see green and I see gray.”88 On the other hand, hostile critics repeated this language in an insulting tone. One sarcastically pronounced, “It is no fault of the ‘intransigent’ system if M. Pissarro sees violet and M. Rouart sees brown.”89 A second lambasted the artists for approaching each motif through a filter predetermined by individual preference, likening their condition to “daltonism” (congenital red-green color blindness).90 A third advised the reader to invert all the colors in impressionist painting to match the artists’ visions: “This painting is black as an oven … so I suppose it must represent the effect of snow on a nice winter morning.”91

The same observation thus enabled opposite conclusions. To Laforgue, the impressionists’ pluralistic palettes evinced their commitment to objectively registering subjective phenomena. To the others, it proved their subjective detachment from objective reality. This split instances the wider cultural phenomenon whereby, counterintuitively, scientific attempts to establish how perception works ultimately promoted skepticism, leading to what Crary terms “a general epistemological uncertainty in which perceptual experience had lost the primal guarantees that once upheld its privileged relation to the foundation of knowledge.”92 Thus, as one critic explained, “If ever one wanted reality, it is assuredly in our century. We even want too much of it, because this pushes men toward general skepticism after which they do not believe what they see.”93

For example, in a much-cited passage, the doyen of experimental psychology, Hippolyte Taine, argued that all perception, whether true or false, begins in hallucination: “What is there within us … when, casting my eyes in a certain direction and having through the retina a sensation of reddish brown, I conclude that there is a round mahogany table three paces from my eyes? A phantom or hallucinatory semblance.”94 He maintained that we can, and almost always do, discriminate between true and false impressions. But he insisted upon giving explanatory priority not to objects but to the sensations they produce: “[E]xternal perception is an internal dream which proves to be in harmony with external things: and instead of calling hallucination a false external perception, we must call external perception a true hallucination.”95 Whereas our intuition may tell us that hallucination (seeing things that are not there) is a defective case of ordinary vision (seeing things that are there), Taine asserts that the latter consists of the former plus an extra ingredient (being true).96

This argument thus easily courts skepticism. For if the optical stimulations caused by real objects can be identical to those in mere hallucinations, then we need some additional evidence to assess their truth. And if we experience a table initially as a patch of reddish brown that may or may not correspond to an object, then differences among individuals’ subjective perceptions—styles of subjectivity—seem to jeopardize our capacity to root our impressions in reality.

Personal and Subjective

As early as 1847, romantic critic and poet Théophile Gautier traced the path from style to skepticism by reinterpreting the parable. Contrasting the women painted by Rubens (sensual), Raphael (virginal), and Rembrandt (inscrutable), he insisted that “We must not conclude that the artist is entirely subjective. He is also objective. He gives and he takes.”97 To drive the point home, Gautier asked the reader to imagine twenty-five painters painting the same mule:

You will get twenty-five completely different donkeys. This one will be gray, that one ruddy, the first will have an austere air, the second the physiognomy of an ingenue. Each artist will have brought out the character most in harmony with his own talent.98

From this story, the author concluded that “painters draw according to an interior model, to which they bend the forms of the exterior model.”99 Yet, Gautier foresaw how this argument could seem to undermine the credibility of universal access to a common world: “Does not such a principle lead us to nullify reality, when we see it reduced to simple appearances? Does not this unbridled idealism suppress the material world?”100

This anxiety would find its definitive articulation in 1874, when Jules-Antoine Castagnary defined the term “impressionism,” writing: “They render not the landscape but the sensation the landscape makes upon them.”101 As many scholars have noted (Richard Shiff preeminent among them), the critic saw dangerous consequences to this apparently innocuous commitment:

In this way, they leave reality and enter fully into idealism …. From idealization to idealization, they will careen toward endless romanticism, in which nature is nothing more than a pretext for reveries, and where the imagination becomes powerless to formulate anything other than personal fantasies, subjective, without echo in general reason, because they are uncontrolled and without possible verification in reality.”102

Because the impressionists adopted the idealist position that one can access reality only as transformed by subjective perception, picturing what that conviction would look like in paint, they effectively ceded any claim to represent reality. Restricting themselves to their own “sensations,” they rendered the world merely a pretext for interesting appearances.

And yet, roughly two decades before he admonished the impressionists, Castagnary had proclaimed that great art is “eminently subjective, the result and the expression of a conception purely personal … of the human self solicited by the exterior world.”103 These two statements seem contradictory. If artworks should express subjective selfhood, then why was impressionist subjectivity so threatening? The answer lies in the critic’s conviction that valid subjectivity remains grounded in intersubjectivity. It is “never, in humanity, an isolated act, unsupported by all the other manifestations of the human. Whatever the vigor of his individuality, the artist is always, not the expression, but the last word of the society around him.” Artists thus draw on their subjective experience to express a deeper, intersubjective commonality, shaped by the social world they inhabit.

Crucially, this process both presupposed and reaffirmed a realist conception of painting as an art, one that the critic defended with a stripped-down version of the parable: “The custom of working face-to-face with nature has freed them from the imitation of masters and memories of school, and their absolute dissimilarities before an identical model, far from attesting their inferiority, is exactly what establishes their value.”104 The more realistic the artists sought to be, the more they revealed that perception is “not a revelation from on high but … the free product of each consciousness placed in contact with external realities,” such that it consequently “varies from artist to artist.”105

In Castagnary’s recitation, each artist participates in a larger collective project not despite their personal subjectivity but because of it. As each artist adds a sincere voice to the collective chorus, “however personal in the procedures he employs,” he contributes to realizing “the sovereign impartiality and pantheistic indifference of universal nature.”106 Thus “one landscape adds to another, and nature, seized in detail by each one, dispersed in fragments across the multitude of works, appears truthfully and resplendently only in the ensemble.”107 The critic thereby held that the stylistic form of subjectivity does not impede our access to reality. On the contrary, we encounter objective reality only through our subjective differences.

Between You and I

When artists paint together, in the parable or in reality, they dramatize a perfectly ordinary practice. In everyday life, we have a proven method of determining what is real. Take the following example, quoted from a nineteenth-century treatise opposing Taine’s “hallucination” argument. Suppose you see an object and cannot tell if it is real or illusory. Then a stranger sees it too. Discussing your experiences, you “discover this identity by the mutual communication afforded by language. Now take a second, a third, a fourth observer …. We thus see that infinitely diverse sensations are coordinated between us such that they suggest a single identical notion.”108 “Illusions,” the same author wrote, “are corrected by the concordant testimony of others (le témoignage concordant).”109 When we confer about our experiences, when I compare my perception with yours, we trust in the world because we trust in one other. The truthfulness of experience is thus socially regulated, essentially interpersonal.110

To make this claim concrete, let us turn to Paul Cézanne, the artist to whom Castagnary addressed his warning against unchecked idealism. The artist’s “hallucinatory” paintings—as another critic dubbed it reviewing the same exhibition—apparently exemplified subjective style as skeptical unhinging from reality.111 Commentators generally hold that it was this peculiarity that Cézanne sought to defuse by his apprenticeship to Pissarro.112 As T. J. Clark writes, he chased “an authority, a voice, a viewpoint beyond the personal—a high and irrefutable impersonality.”113 Finding it, however, required “first of all, not being impersonal … but being someone else,” demanded “the to-and-fro of contrary personalities: a suspension of personality for a time, an impersonation, the creation of a double.” Thus the “graceless, immature, belligerent, foolhardy” artist sought out Pissarro to “unlearn his first style.” To escape hallucination, Cézanne needed a different relation not to the objective world but to another subjective style.

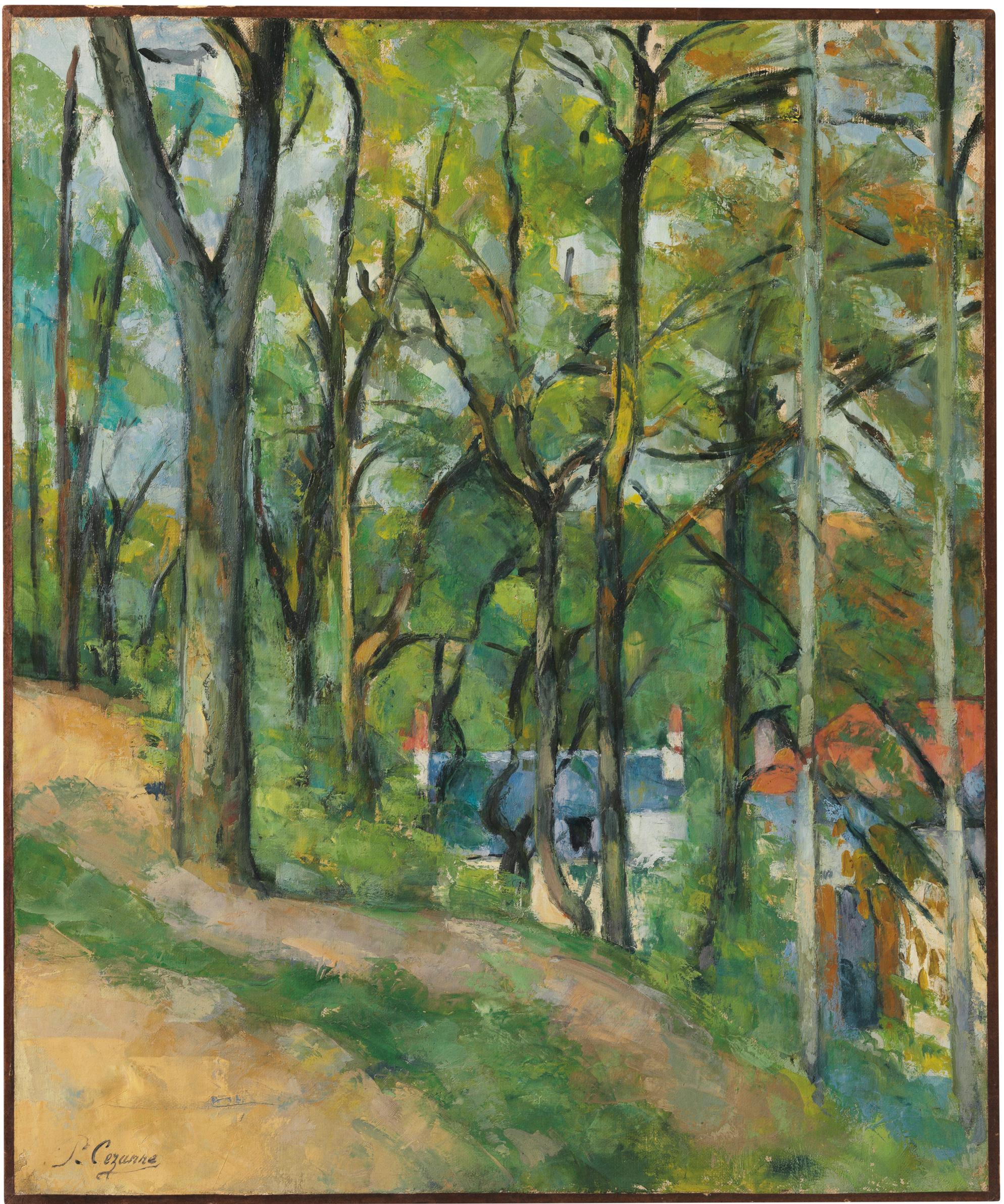

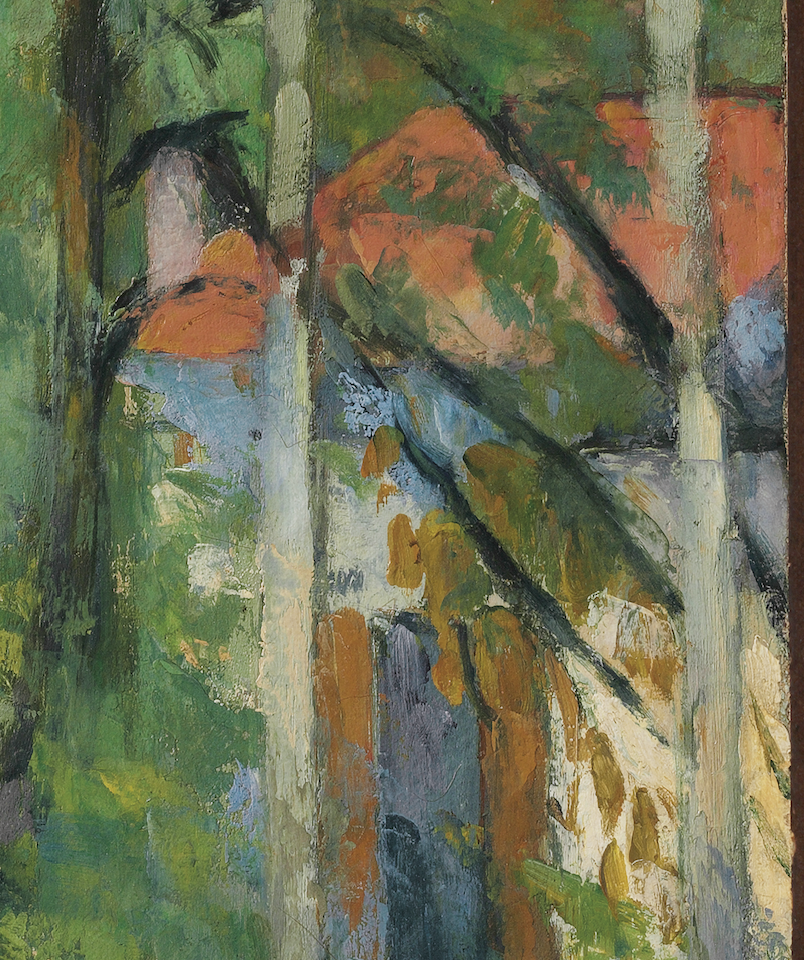

Compare his painting of a forest in Pontoise with Pissarro’s of the same motif (figs. 15 and 16). There is little convergence between the artists’ palettes, compositions, or factures.114 Pissarro employed muted colors, which unite the whole as though viewed through a soft lens, chromatic difference mostly keyed to that of the objects described. Cézanne rendered his view in vivid tones, even layering in apparently unmotivated hues—as in the blue-grays and taupes that dapple the dirt at the bottom left (fig. 17). Pissarro chose a position from which the houses, while screened by parallel rows of trees, sit obliquely to the picture plane. They thus suggest a spatial depth further secured at bottom left by the furrows of a path, and at bottom right by a foreground clearing, which separates the viewer from the motif. Cézanne, meanwhile, refused perspectival cues by facing the houses, tilting the path upward to confound its recession, and omitting the clearing. Pissarro encrusted the canvas with layers of dried paint, yielding a relief surface of variegated texture. Cézanne slabbed large streaks on with a palette knife and scumbled thin strokes on top, playing with the difference between seeing the marks as depictive means and depicted objects.

One might cite these very different approaches to illustrate the skeptical consequences of treating subjectivity as stylistic. If both artists truly painted what they saw, and if their works look so different, then we are again left with the problems of verification and reconciliation. Yet look at the right-hand side of Cézanne’s painting, at the orange roof cut by the slashing trunks. Notice how that bark lacks solidity, how it here lifts off the surface in individuated opaque strokes and there tunnels under its encroaching surrounds (fig. 18). Ask yourself, what is that cerulean doing there, between the roof and the wall? Or the more muted, somber rectangle of blue below? These marks seem unmoored from meaning—until, that is, one looks at Pissarro’s accompanying view. There, we find what this passage describes, see how Cézanne amplified the blue tones of reflected shadows under the roof, how he focalized the grayish door in his obtrusive quadrilateral, how he congealed the screening foliage that Pissarro rendered as bursting flecks, Cézanne as interlocking smears.

Together, these works point to the intersubjectivity of intentionality—to the way that we depend on one another for the objective validity of our experience.115 They portray our access to reality as dependent on social relations, on the corroborating presence of others with whom we hold the world in common. The artists could thus use personal style to evince subjective perception while catching objective reality in an intersubjective net. As Cézanne remarked, “Between you and I, there is the world … what we see in common.”116

Notes

This essay reframes chapter one of my forthcoming book, Painting with Monet (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024). I wish to thank Bridget Alsdorf and Marnin Young for inviting me to participate in this issue and, more importantly, for being generous mentors and interlocutors since I started in this field. My argument also benefited from a very thorough peer review, and from discussions with Jordan Cotler, Peter Galison, Abram Kaplan, Carmen Rosenberg-Miller, and Jensen Suther.In 1862, a young critic, Théodore Duret, learned that two titans of contemporary painting, Camille Corot and Gustave Courbet, were visiting his hometown in Saintes. Rushing to meet them, he found the artists on the top of a nearby hill overlooking the commune. To his astonishment, the two had planted their easels side-by-side, “far enough away that they could not see each other’s work, but close enough so that they could exchange ideas and conversation.”1 Duret watched, awestruck, as they began to work. “They painted their views on little canvases of the same dimensions and agreed to stop working at the same time” (figs. 1 and 2).

Observing their process, Duret marveled at their commitment to painting what they saw. “When they painted before nature, they rendered its aspects without changing anything.”2 Seen together, the pair of paintings revealed something that neither could disclose on its own. “These two works, executed simultaneously by Courbet and Corot, can help us to recognize the common principles that they followed.” Individually, each painting might conceal some adjustment to the landscape, changes made to improve or prettify the world that it depicted. Together, they kept each other honest, for so long as they clung “as close as possible to the texture of the landscape that they had beneath their eyes,” then anything in one artist’s view should also appear in the other’s.3 Collaboration became corroboration as “they applied themselves to fixing with exactitude the things seen.”

Years later, both works that Duret had seen in progress happened to be listed in the same auction. When the critic came upon them, they transported him back to that summer’s day:

What struck me above all was the fidelity with which the aspect of the places was rendered. The steeples of the churches Saint-Pierre and Saint-Europe, so particular, were on the canvas in the exactitude of their form. The local vegetation, characterized by the leaves of the elms which naturally grow there had been seized in all their truth.

Based on this celebration of “fidelity” and “exactitude,” one might expect the two paintings to be near-identical, to differ only in ways commensurate with the small distance between the artists’ easels. Duret was surprised to find, however, that “the two paintings [also] revealed the individual manner belonging to both artists, more tender in the Corot, more severe in the Courbet.” Somehow the artists both painted exactly what they saw and revealed themselves as individuals.

Because they possessed an enlarged sensibility, such that they vibrated before nature and experienced emotion in contemplating the scene, that sentiment worked its way into the paintings that they painted. It constituted them as works of art. It became one with them and animated them, not as an added ingredient or due to reflection, but as an intrinsic part of the execution, without the artists even realizing it.4

Watching the two artists work helped Duret to see this unexpected synthesis of apparent opposites, impersonal exactitude and personal temperament.

As he tried to explain how this fusion was possible, his analysis burst like buckshot with essential but enigmatic terms, “sensibility” and “sentiment” versus “fidelity” and “exactitude,” oppositions that were crucial to the art theory of his time. At their root was the enigmatic distinction between subjective perception and objective reality, which, to Duret, the practice of painting side-by-side uniquely rendered visible. When the critic sat on that hill in Saintes, these terms were still unsettled, not having fully filtered down from philosophers and Germanophiles into everyday use.5 And while he did not use them when recounting the meeting of Corot and Courbet, we will see that the tale gives them an ostensive definition: subjectivity means whatever it is that causes two artists painting the same scene to see it differently.

In this respect, Duret’s story typifies what I shall call the parable of the painters: imagine two artists, each copying exactly what he sees, only to find that their works look different. As early as 1818, a treatise on landscape asserted that many artists’ paintings of the same viewpoint would differ according to “the diversity of their organs and their sensations.”6 By 1873, one critic prefaced his use of the heuristic—“place ten artists before the same landscape”—by acknowledging that “the following argument has been somewhat overused.”7 It became so firmly entrenched that it entered the highly codified realm of standardized testing, as in a 1902 textbook for the baccalaureate in philosophy, which prompted students to prove that “the faithful imitation of nature is impossible” by imagining two artists painting the same landscape.8

Ultimately, the parable became nothing less than an origin story for art history as an academic discipline, recited in the famous opening paragraph of Heinrich Wölfflin’s urtext, Principles of Art History (1915). There, when four artists noticed how differently they rendered a scene painted side by side, they discovered comparison as an art historical method—becoming distant ancestors of all students who learn to look at artworks in a classroom, where our teachers project two slides and compare them.9 But, to Wölfflin, those four artists revealed not only style but subjectivity, realizing in a flash that “there is no such thing as objective vision.” Likewise, when E. H. Gombrich retold the same story in Art and Illusion, he characterized its import as picturing “the limits of objectivity.”10 With these phrases, they stated plainly the lesson the parable had always taught: that when multiple artists paint the same thing, each trying his hardest to reproduce exactly what he saw, they end up with different paintings because they saw the same thing differently.

By the time it reached Wölfflin, however, the parable had spread far beyond its initial use in art theory, deployed formulaically whenever an author needed to explain the limits of objectivity. Here, for example, is how Gustave Le Bon argued that no historian can impartially recount events:

The historian sees events like the painter sees a landscape …. Many artists, placed before the same landscape, will necessarily translate it each in his own fashion …. Each reproduction will thus be a personal work, that is to say, interpreted by a certain form of sensibility. It is the same for the writer. One can thus no more speak of the impartiality of a historian than that of a painter.11

Le Bon thus used the tale to assert a fundamental principle: the unavoidable subjectivity of social science. He saw it as proof that there is no such thing as objective representation. A work of history, like a painting, always has a style.12

A text search using Gallica (the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France) produces many more such examples.13 The parable became a pedagogical staple, repeated in textbooks on prose composition, intellectual property, and jurisprudence.14 Authors employed it whenever they wanted to explain how different people can experience the same thing differently. How could many citizens have conflicting views of the July Revolution?15 Why do multiple sommeliers give contrasting descriptions of the same wine?16 What explains the diverse worldviews of African tribes?17 Why do the four Gospels disagree on basic points?18 How can two actors interpret Hamlet nearly antithetically?19 Well, imagine two painters painting the same landscape.

As the parable migrated from art criticism to the wider world, its purpose changed. Initially, it was used to understand artistic style, especially to shift the register of explanation from manual causes (the way a painter holds his brush, the materials he chooses, etc.) to cognitive ones (the way he sees and understands the world). With repeated retellings, however, cause and effect flipped. Instead of proving that style is subjective, the parable seemed to reveal that subjectivity is stylistic.

Here, then, is our agenda: to trace how a question about style became a theory of subjectivity. In so doing, I do not seek to endorse that theory—to say that we should see subjective experience as a style of mindedness. Nor am I willing to concede its central inference—that if different artists represent the world differently, it must mean that they see it differently. On the contrary, the parable interests me precisely because it offers an image of subjectivity that is lucid enough to criticize, concrete enough to dispute.20 That clarity follows from the scenario’s roots in historically specific image-making practices. While most individual recitals invent hypothetical artists as stripped-down heuristics—in Wölfflin’s and Gombrich’s citations of Richter’s tale, for instance, the actual artworks required no specific comment—the story presupposed and challenged definite developments in artistic practice.21 To tell it in abstract thus means missing its true significance, which emerges only when we assay these theories in the fire of practice.

That practice: artists painting side by side. Long a staple of art school training, wherein rows of students all copied the same model as they learned to draw and paint (fig. 3), side-by-side painting became its own genre in the early nineteenth century, especially in France, prompted and enabled by wider, more familiar developments in the history of French painting. At that point, an emergent realist paradigm overturned existing conventions of landscape as an art. Painters began committing, at least rhetorically, not to modify or arrange the objects of their vision but rather to copy them exactly as they appear. As the century progressed, this mode gave rise to another variant, impressionism, which emphasized the word “appear.” The impressionists attended to the specific cognitive and physiological form of perception, and, in the process, highlighted the subjectivity already involved in the reception of realist painting. These movements joined another incipient challenge to dominant theoretical and practical paradigms: photography. If the realists and impressionists promised to render what they saw without intervention, photographers claimed this neutrality as an automatic feature of their process. Together, these developments prompted a major reassessment of the epistemological premises at stake in representation.

This essay thus traces the somersaulting feedback between the theoretical possibilities and historical reality of painters painting the same thing, tracking critical recitals and selected painted examples. While the parable proved useful beyond nineteenth-century France—Wölfflin’s source, Richter, is especially interesting—I concentrate on this period as a uniquely fertile ground thanks to its singular combination of institutional factors: first, its prominent insurgent artistic movements (realism and impressionism) and, second, well-developed, robust institutions of criticism that encouraged real-time engagement with contemporary developments.22 This history involves close attention to small variations in the evolving recitals of this parable, sources that, in their obscurity, might appear of interest only to specialists in nineteenth-century French art and theory. For that reason, I begin with a later retelling of Wölfflin’s example, one that shows how my arguments bear on key debates in the history of knowledge.23

Styles of Painting, Styles of Knowing

To explain why scientific reasoning does not exhaust genuine knowledge, Ernst Cassirer reached for the parable. Science, the philosopher explained in 1944, searches for objective principles from which we may derive all particular phenomena—e.g., once a chemist knows how many protons occupy an atom’s nucleus, “he may deduce all the characteristic properties of the element.”24 Art, by contrast, refuses deductive reasoning. Just the opposite, whereas science seeks to uncover the objective laws governing reality, art celebrates the proliferation of subjective experience.

To argue this point, Cassirer repeats Wölfflin’s story and quotes the latter’s conclusion that there is no such thing as objective vision. Insofar as their works differed, Richter and his friends demonstrated the world’s resistance to exhaustive objective description. Rather, they showed how visual experience constitutes its own kind of knowledge, subjective but no less real than scientific reasoning. And so, as Cassirer writes elsewhere, “to the extent that we can have knowledge through visible and tangible forms … style is rooted in the deepest foundations of knowledge.”25

With such claims, Cassirer helped inaugurate an enduring problematic in the history of knowledge, which has come to be called “styles of reasoning.”26 This term refers, as Arnold Davidson explains, to “the conditions under which various kinds of statements come to be comprehensible.”27 Building on this definition, Ian Hacking notes that styles of reasoning help us understand what we mean by objectivity, “not because styles are objective (i.e., we have found the best impartial ways to get at the truth), but because they have settled what it is to be objective.”28 He thus compares styles of reasoning to Kant’s transcendental categories as means of explaining “how objectivity is possible … preconditions for the string of sensations to become objective experience.” For Kant, categories like causality cannot be established in experience (as though there was some raw consciousness to which cause could be added) but are rather conditions for us to experience anything at all. Likewise, styles of reasoning are not more or less objective but instead explain “how objectivity is possible … [They are] preconditions for the string of sensations to become objective experience.”

Whereas subjective experience evidently differs among individuals, societies, and historical periods, objectivity seems, by its own definition, universal and constant. This intuition, however, belies a complex history whereby the criteria for objectivity—ascribed variously to claims, beliefs, and institutions—have changed over time.29 If the meanings and uses of “objectivity” vary among communities, then the concept itself cannot be objective in the usual sense. Thus, writes Steven Shapin, “that which seems to be transparently about objects in the world contains ineradicable elements belonging to subjects, their background knowledge, their categories, customs, conventions, and purposes. Our scientific knowledge is about the world and it is also irremediably about us, as knowers. And the condition of our knowledge being intelligibly about the world is that it contains a bit of us.”30

In the most comprehensive history of objectivity, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have traced the concept through a series of what they call “images” (O). This word functions both figuratively and literally. Literally, it means varieties of pictures used to obtain and disseminate objective knowledge (medical illustrations, photographs, etc.). Figuratively, it means the varying conceptions of objectivity that these pictures enable us to differentiate and classify (truth-to-nature, mechanical, etc.). The authors’ aim is not to assess whether a diagram or an x-ray are really objective images but rather to elucidate how the conceptual differences between those practices enable reflection on the conceptual history of objectivity. “[These] specific forms of image-making sculpt and steady particular, historical forms of the scientific self,” such that we can delineate styles of objectivity by attending to histories of image-making practices (O, 4).31