The Anti-Dictionary: Ferreira Gullar’s Non-Object Poems

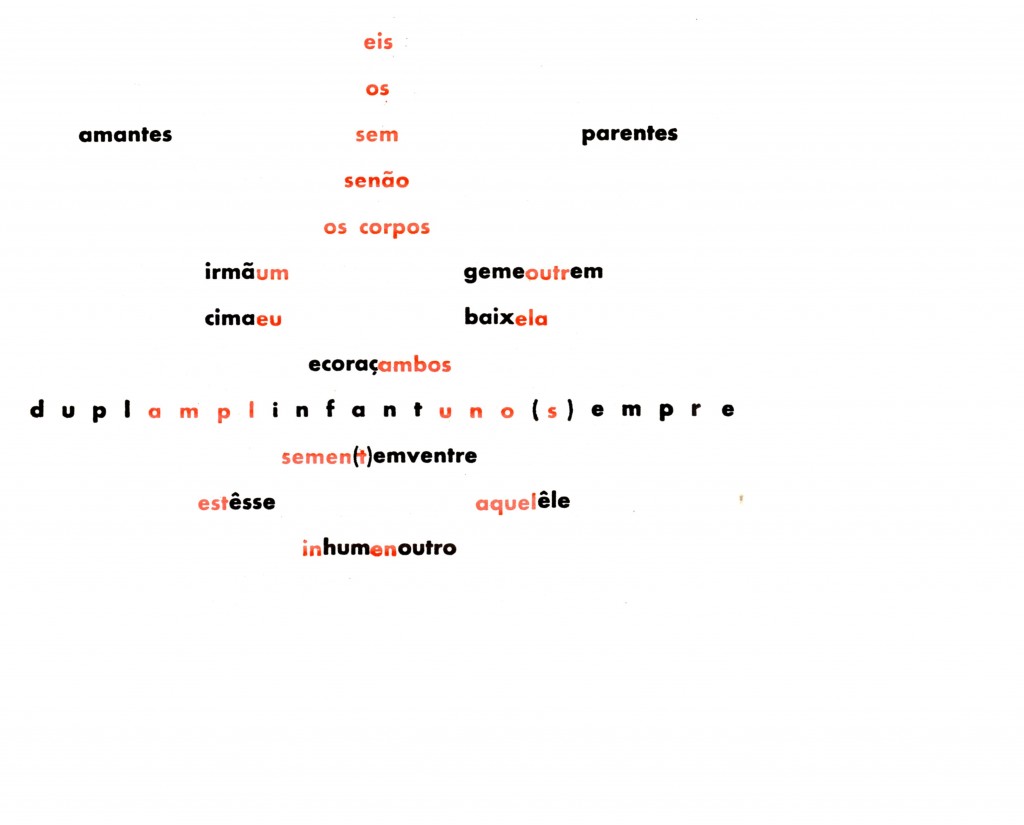

Gullar gave primacy to the word as the locus of meaning of the non-object poem, and the visual, whether the materiality of language or the sculptural turn of his Neoconcrete art, opened up additional meanings contained in the word. According to Gullar the non-object as anti-dictionary cannot be reduced to one meaning or limited to only an arbitrary sign. Like the visual non-object, the verbal non-object avoids sameness or commonness and rejects the ability of language to only designate. And yet paradoxically, are not all words readymades themselves?