The text that follows originally appeared in 2018. I wrote the essay at my godfather Joseph Marioni’s invitation. Joe was in the midst of planning a major exhibition—the largest of his career, essentially a retrospective—at the Museum Wiesbaden in Germany, and he wanted a retrospective-style essay for the catalogue. I had been living in the little guest room of his Midtown Manhattan studio for more than two years (a temporary stay when I finished my master’s at the New School gradually and joyfully became un-temporary), and our countless and endlessly rich conversations about and in front of his paintings during that time prepared me, he thought, to deliver a comprehensive explanation of the development of his work over nearly 50 years.

It took me three tries to get it right; an earlier draft, focusing much more on what I call Joe’s paintings’ astonishing sense of “internality” despite the seeming density of their surfaces, he deemed “too theoretical.” Not that Joe was allergic to theory—far from it. His own writing about his painting was theoretically sophisticated (his work was, in a favored phrase, part of “the transition from pictorial representation to concrete actualization”), and his longstanding dialogue with Michael Fried had been instrumental, he often said, in his development as a painter (See “Footnote Number 6: Art and Objectness,” republished in this special issue). My understanding of Joe’s work had been deeply marked by Fried’s famous review in Artforum of the 1998 show at Brandeis, the show that occasioned their meeting (see Fried’s poem, “Marioni at Brandeis,” also in this issue), particularly Fried’s concluding thought, that Joe’s was “the first body of work I have seen that suggests that the Minimalist intervention may have had productive consequences for painting of the highest ambition.” This insight heavily informed my “theoretical” interest in Joe’s painting: what it meant for painting to pass through the crucible of objecthood, retain the physicality discovered therein, but then restore to itself the internality essential to all great painting—not illusionistic internality, but an internality, in Joe’s case, of sheer “liquid light.”

I rewrote the too-theoretical version of the essay, and he was happy with the result. He would often say, when forced to hire a graphic designer to produce an exhibition poster or new business cards, that he “wanted an engineer, not a designer.” That is, he was the designer, and he wanted someone to execute his design. This essay was far from an engineering job. The occasional infelicities of conception—including the questionable opening distinction between “paradox” and “dialectic”—are designers’ problems. But I tried here to tell the story of his development the way, more or less, that he wanted it to be told. As he liked to say, the essay “made the point.” There will be more too-theoretical essays on Joseph Marioni to come, including from me, but it was one of the great honors of my life to make the point while Joe was still here with us to see it made.

In the critical writings on the paintings of Joseph Marioni, certain expected words occur frequently. It comes as no surprise, of course, that “paint,” “color,” and “light” permeate the literature—even the most casual observer of Marioni’s work can recognize that these fundaments of painting are his central concerns.

Yet there is another, more surprising word that pops up regularly in reviews and catalogue essays: “paradox.” One writer, for instance, might note the seeming paradox between the monochromatic appearance of Marioni’s paintings and their actual multihued structures; another may describe the paradoxical relation between the paintings’ manifest materiality and their nonetheless inescapable shift toward dematerialization.1 Indeed, once one learns how to look, the apparent paradoxes begin to proliferate: stillness and movement, unity and multiplicity, flatness and depth, liquid and light. Soon enough, it seems as though there is no single quality in a work of Marioni’s that will not find itself challenged moments later by its opposite.

Yet “paradox” does not seem quite the right word to describe all this. Paradox would seem to imply irreconcilability, the impossibility of resolution, or at the very least resolution’s eternal deferment. But Marioni’s work, as his commentators would surely agree, manages to subsume these so-called paradoxes into the untroubled, unconflicted integrity of the painting itself, painting that is singular in its statement despite, or perhaps in some sense because of, its complex and multivalent resonances. A subtle semantic shift brings this reality more clearly into view: Marioni’s achievement might be understood not as paradoxical but as dialectical.

I want to look specifically at three dialectical relationships within the work of Joseph Marioni, mapped roughly onto the three stages, as he delineates them, of his nearly 50-year career. The dialectics of Marioni’s painting have emerged from a developmental process which has itself been thoroughly dialectical. If we can better grasp that process, we may better grasp the works themselves beyond their paradoxical appearances.

Painting / Object

Marioni understands our moment in the history of painting as “a transition out of the composition of a picture-form and into the structural identity of the painted-form, a paradigm shift from pictorial representation to concrete actualization.”2 A critical aspect of painting’s actualization has been the awakening of what Marioni calls its essential “objectness”: its status as a physical object on the wall, a status which had been concealed prior to the 20th century by pictorial illusionism and the picture frame. The first stage of Marioni’s career shows his attempt to access and materially isolate the objectness in his own paintings.3

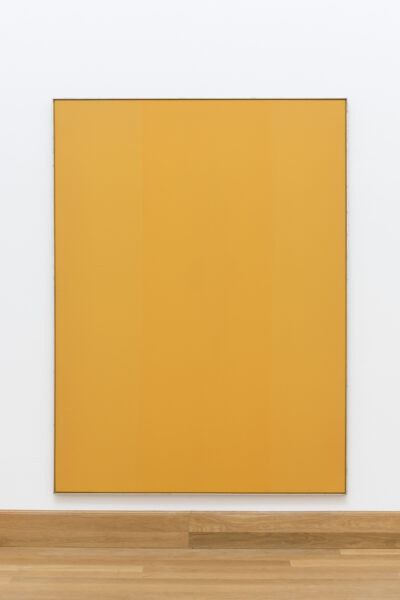

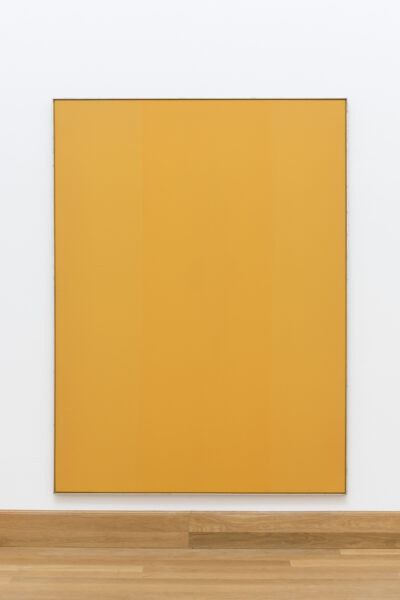

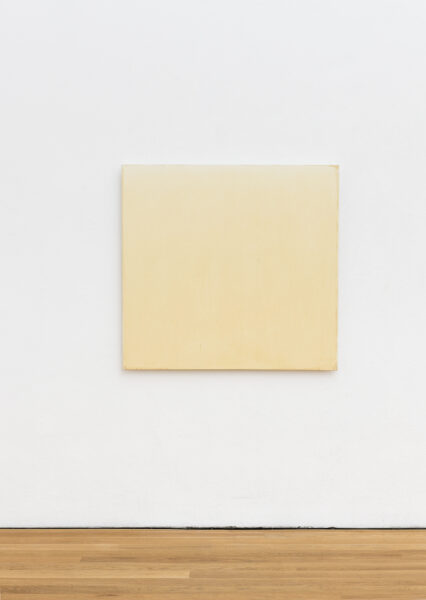

This initial period of exploration, lasting roughly ten years, can itself be split into two distinct bodies of work. The paintings of 1970, the point at which Marioni officially begins documenting his work, feature matte monochromatic grounds of bright colors, on top of which two extremely subtle diagonal bands of lighter or darker shades appear to overlap one another. These bands read almost as shafts of light suspended in the colored ground; one tends to be immediately legible while the second verges toward complete invisibility. The most recognizable feature of these paintings is their strong overall color identity—bright yellow in the case of one work, 10-70, from this inaugural year (Figure 1). The paintings are also framed, a detail that those familiar with Marioni’s mature work might find quite surprising.

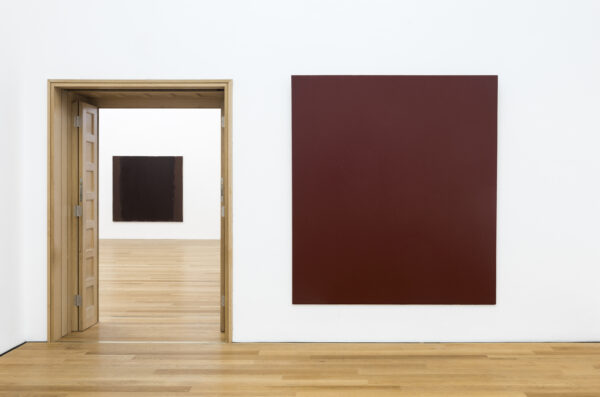

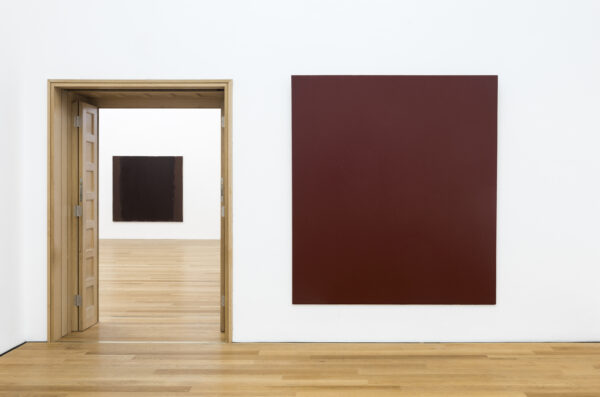

Yet it is clear that multiple aspects of this period bothered Marioni. For one, the paintings were still fundamentally illusionistic, still predicated on a figure-ground relationship, however minimal. Within a few years, he would expunge all figuration and replace it with a pure, pungent materiality; this stage witnesses the emergence of Marioni’s signature drips, as well as his first investigations into constructing his paintings from multiple layers. In another work, this from 1974 (Figure 2), we find in place of the shaft of light a densely and roughly painted cascade of very dark brown pigment running down the canvas’s center, layered multiple times until the color nears black. Over the next several years, Marioni (having now removed the picture frame entirely) widens this new band of pure paint until it surrounds the edges, in effect abolishing the figure-ground relationship by expanding the figure until it simply becomes the entire painted surface. Also essential here is Marioni’s new method of hanging the works from metal loops at roughly middle height on either framing edge, which has the effect of dramatically tilting the painting into the viewer’s space in an aggressive assertion of physicality. By the time we get to Painting 4-81 from 1981 (Figure 3; note that Marioni has begun to add the word “Painting” to his numerical titles), this stage appears to have reached its culmination. Marioni had finally located his paintings as objects on the wall, objects that could “hold the wall.”4

Yet having achieved this, Marioni quickly discovered that, for a painting, simply being an object, however fully materially realized, was not enough to give it an identity as a painting; he had instead produced what he’s referred to as “painted objects.”5 Though they were strong works, and developmentally essential, Marioni had already perceived the next necessary step: Without, on the one hand, stripping away objectness, or, on the other, retreating back into the defunct pictorial strategies of figure and ground, he had to achieve what we might call paintingness. He would do this through the reintroduction of that with which he had begun: color.

Structure / Color

Marioni in essays and interviews often poses rhetorical questions to get us analytically deeper into the heart of the painting problems he is confronting. One of the most incisive comes from the Venetian Renaissance painter and theorist Paolo Pino, who inquired as to the fundamental difference between color in a jar and color in a painting.6 Color is already beautiful before it is applied to the canvas, his argument goes; for the painting to have a purpose, then, it must add something that the raw paint does not inherently contain. For Pino, the missing ingredient is the painting’s artful placement of the color among other colors in the overall composition.

Pino’s answer would seem to rule out the monochrome, which makes his original question all the more germane here. For single-color painting to be a worthwhile pursuit, it must somehow be doing something with color beyond the latter’s straightforward presentation, something that doesn’t have to do with compositional juxtaposition. What is it?

Color erupts back into Marioni’s paintings beginning around 1980—oranges, yellows, reds. But Marioni could see that he had to, in effect, answer Pino’s question. It would take five or more years of investigation for him to do so, and when his mature work begins to emerge in the late 1980s, the answer couldn’t be clearer.

The first step was the development of techniques to inflect and deepen the late-’70s “painted objects,” techniques that concerned themselves with the deliberate structuring of the paint and its relation to the support. He began building each painting as a “body color,” the basic format of which consisted of three layers: an opaque ground, a translucent middle color, and a transparent glaze (“the bones, the meat, and the skin”). Concurrent with this development was the emergence of Marioni’s other well-known techniques, such as allowing the paint to draw in from the edges of the support as it descends during the painting process and tapering the frames slightly toward the bottom to enhance this effect. Through this drawing in, he began subtly revealing some of the underlayers of each “body color,” calling attention to its composite structure. And he began rounding the lower edge of each stretcher so that the drips of paint would run off rather than gather into a line; he frequently lets these drips terminate well above the bottom of the support, creating another area in which underlayers can be perceived.7 All of these innovations had the effect of developing an internal boundary in the painting, one which did not re-create the figure-ground problem of the earliest efforts but which nonetheless restored a certain kind of interior depth that made these works more than solid surfaces, more than mere painted objects—a depth that made them paintings, “in the fullest and most exalted sense of the word,” as Michael Fried wrote in his review from this period.8 (You can find this hard-won internality on full display in Green Painting from 1992 (Figures 4 and 5), for instance. Note that he also abandoned the metal-loop hanging system in this stage, returning to hanging his paintings from the upper center and lessening, though not entirely eliminating, their tilt forward.)

The exploration of color was, of course, inextricable from these developments. Every decision about size, shape, layering, and structure that Marioni made for each painting was geared toward revealing something specific about whatever particular color he was working with. Marioni has written that this period emerged from his “recognition that color is the very reason for painting’s existence in the first place.”9 We find in these works too the full expression of his belief that each color has a size and shape most proper to it, most conducive to disclosing its specific personality, related to what he calls that color’s “archetype.” The relationship between color and archetype is part of what evokes a particular “feeling response” from the viewer. As he wrote in a 2002 essay:

It does seem to me there might be some form of an archetype to the colors of the painter’s palette, some structure that corresponds to our feeling response to color. Like earth, air, fire and water the colors of vision form structures that are characteristically distinct from one another and somehow intrinsic to each. If the creation of a painting is determined by our feeling response to the color and not just the concept of the artist, then the gestalt of the painting as an object should have some structural parallel to the archetype of its color…. This means, of course, that you cannot [make a blue painting] the same way you paint yellow, green or red.10

Accordingly, his red paintings tend to be more vertical to correspond to the body of the viewer, for example; yellow paintings tend to be square, relating them to our archetype for yellow, the sun. (Some of the paintings Marioni deems failures and destroys are works whose only evident defect is that they seem to be the wrong size and shape for their particular color.)We can already see the beginning of an answer to Pino’s question as it might be put to monochrome. The difference between color on a palette and color on a painting is that the painter’s specific decisions about structuring the painting—from the size and shape of the support to the particular building up of the paint itself—embody that color in a way that reveals something essential to it. As Marioni puts it, the painting’s entire “aesthetic value” is in nothing other than “the painted quality of the color within the gestalt of the painting as an object. That quality is dependent on how we materially structure the color.”11

Liquid / Light

The third phase of Marioni’s development, the phase in which he is still working today, begins in the mid-to-late 1990s. By this point he had gained mastery over his materials and was already painting major works which were bringing into equilibrium all the considerations he had spent the previous two decades wrestling with.

Yet there remained one element that had not yet received its due exploration, that element which is painting’s very condition of possibility: light.

Color, as Marioni regularly reminds us, is “divided light.” In terms of the sequence of events in the construction of a painting the painter first mixes pigment (the source of the paint’s color) into a medium (which has no coloristic properties unto itself; in Marioni’s case, the medium is acrylic). The resulting paint is then applied to the support, and the pigment, having been bound to the support by the medium, divides the light, i.e. “it holds some wavelengths and reflects back others. That light is revealed to us as color.”12

Though the chemical reality of this sequence is simple, its negotiation by the painter is anything but. Though any painted surface will necessarily divide light, it is the painter’s task to locate the light somewhere specific within the painting’s overall structure. “The game I play is the placement of the light in the painting,” Marioni has recently said. “Is it inside the painting? Is it on the surface? Does it come forward?”13

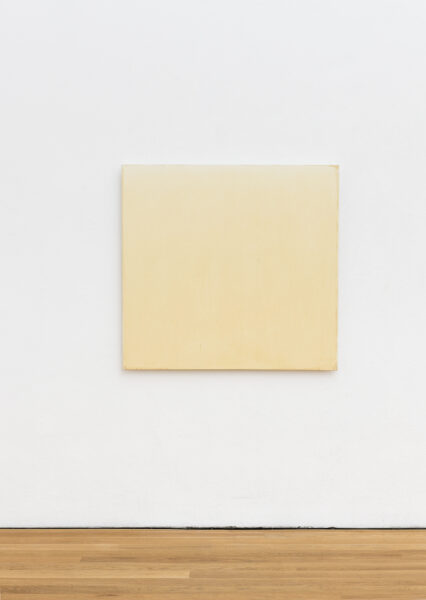

For Marioni, Rembrandt, as a varnish painter, enclosed his light inside the painting, strategically and sparingly allowing it to leak through in crucial passages. Monet, meanwhile, was known to bring the light to the very surface, and even beyond: Marioni describes a particular Monet at the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland whose water lilies, at certain times of day, produce a “perfume of blue that you walk through.” Marioni describes a similar effect in a yellow painting of his own, which is built on a foundation of pearlescent pigment whose silver quality retains no light and instead “pushes it all out.… So the light of the painting feels to be in front of the painting; it’s coming off the surface.”14 (2016’s Light, in the present exhibition, demonstrates a similar outward placement of light (Figures 6 & 7).)

The placement of the light is part pure color chemistry, to be sure, but it also depends on an acute awareness of the fact of the painting’s physical environment and the light present in that environment. This discovery relates this third stage of Marioni’s evolution to his first, in which he discovered the material reality of the painting as object; this stage too has been an acknowledgement of the painting as a physical object in space. “The perceptual context of a painting is the atmosphere of the environment in which it hangs,” Marioni writes, and this context, for the painter, is not an afterthought; it is, in fact, primary.15 As he puts it in a characteristic aphorism, “In the architecture of concrete painting, function follows light.”16

In speech and in practice, the term “liquid light” binds together the material and the immaterial; indeed, this binding is at the core of all painting. And it is the dialectical acknowledgment performed by the notion of liquid light that, finally, gives Marioni pride of place at this epochal moment in the history of his art form. If painting is in the midst of a transition “from pictorial representation to concrete actualization,” this actualization depends on the absolute recognition of painting’s most fundamental properties. Yet individual recognition is not enough; those properties must also be fused to one another in a relation of continuous interplay—of structural interdependence.17 This relation, when attempted, may strike us as paradoxical. Only the failure or success of the painting will tell us if it is that, or something more.

Notes

This essay originally appeared in Liquid Light: Joseph Marioni: Painter, Museum Wiesbaden/Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2018. Nonsite thanks Hengesbach Gallery for providing digital copies of the catalog photographs by Bernd Fickert.

The text that follows originally appeared in 2018.* I wrote the essay at my godfather Joseph Marioni’s invitation. Joe was in the midst of planning a major exhibition—the largest of his career, essentially a retrospective—at the Museum Wiesbaden in Germany, and he wanted a retrospective-style essay for the catalogue. I had been living in the little guest room of his Midtown Manhattan studio for more than two years (a temporary stay when I finished my master’s at the New School gradually and joyfully became un-temporary), and our countless and endlessly rich conversations about and in front of his paintings during that time prepared me, he thought, to deliver a comprehensive explanation of the development of his work over nearly 50 years.

It took me three tries to get it right; an earlier draft, focusing much more on what I call Joe’s paintings’ astonishing sense of “internality” despite the seeming density of their surfaces, he deemed “too theoretical.” Not that Joe was allergic to theory—far from it. His own writing about his painting was theoretically sophisticated (his work was, in a favored phrase, part of “the transition from pictorial representation to concrete actualization”), and his longstanding dialogue with Michael Fried had been instrumental, he often said, in his development as a painter (See “Footnote Number 6: Art and Objectness,” republished in this special issue). My understanding of Joe’s work had been deeply marked by Fried’s famous review in Artforum of the 1998 show at Brandeis, the show that occasioned their meeting (see Fried’s poem, “Marioni at Brandeis,” also in this issue), particularly Fried’s concluding thought, that Joe’s was “the first body of work I have seen that suggests that the Minimalist intervention may have had productive consequences for painting of the highest ambition.” This insight heavily informed my “theoretical” interest in Joe’s painting: what it meant for painting to pass through the crucible of objecthood, retain the physicality discovered therein, but then restore to itself the internality essential to all great painting—not illusionistic internality, but an internality, in Joe’s case, of sheer “liquid light.”

I rewrote the too-theoretical version of the essay, and he was happy with the result. He would often say, when forced to hire a graphic designer to produce an exhibition poster or new business cards, that he “wanted an engineer, not a designer.” That is, he was the designer, and he wanted someone to execute his design. This essay was far from an engineering job. The occasional infelicities of conception—including the questionable opening distinction between “paradox” and “dialectic”—are designers’ problems. But I tried here to tell the story of his development the way, more or less, that he wanted it to be told. As he liked to say, the essay “made the point.” There will be more too-theoretical essays on Joseph Marioni to come, including from me, but it was one of the great honors of my life to make the point while Joe was still here with us to see it made.

In the critical writings on the paintings of Joseph Marioni, certain expected words occur frequently. It comes as no surprise, of course, that “paint,” “color,” and “light” permeate the literature—even the most casual observer of Marioni’s work can recognize that these fundaments of painting are his central concerns.

Yet there is another, more surprising word that pops up regularly in reviews and catalogue essays: “paradox.” One writer, for instance, might note the seeming paradox between the monochromatic appearance of Marioni’s paintings and their actual multihued structures; another may describe the paradoxical relation between the paintings’ manifest materiality and their nonetheless inescapable shift toward dematerialization.1 Indeed, once one learns how to look, the apparent paradoxes begin to proliferate: stillness and movement, unity and multiplicity, flatness and depth, liquid and light. Soon enough, it seems as though there is no single quality in a work of Marioni’s that will not find itself challenged moments later by its opposite.

Yet “paradox” does not seem quite the right word to describe all this. Paradox would seem to imply irreconcilability, the impossibility of resolution, or at the very least resolution’s eternal deferment. But Marioni’s work, as his commentators would surely agree, manages to subsume these so-called paradoxes into the untroubled, unconflicted integrity of the painting itself, painting that is singular in its statement despite, or perhaps in some sense because of, its complex and multivalent resonances. A subtle semantic shift brings this reality more clearly into view: Marioni’s achievement might be understood not as paradoxical but as dialectical.

I want to look specifically at three dialectical relationships within the work of Joseph Marioni, mapped roughly onto the three stages, as he delineates them, of his nearly 50-year career. The dialectics of Marioni’s painting have emerged from a developmental process which has itself been thoroughly dialectical. If we can better grasp that process, we may better grasp the works themselves beyond their paradoxical appearances.

Painting / Object

Marioni understands our moment in the history of painting as “a transition out of the composition of a picture-form and into the structural identity of the painted-form, a paradigm shift from pictorial representation to concrete actualization.”2 A critical aspect of painting’s actualization has been the awakening of what Marioni calls its essential “objectness”: its status as a physical object on the wall, a status which had been concealed prior to the 20th century by pictorial illusionism and the picture frame. The first stage of Marioni’s career shows his attempt to access and materially isolate the objectness in his own paintings.3

This initial period of exploration, lasting roughly ten years, can itself be split into two distinct bodies of work. The paintings of 1970, the point at which Marioni officially begins documenting his work, feature matte monochromatic grounds of bright colors, on top of which two extremely subtle diagonal bands of lighter or darker shades appear to overlap one another. These bands read almost as shafts of light suspended in the colored ground; one tends to be immediately legible while the second verges toward complete invisibility. The most recognizable feature of these paintings is their strong overall color identity—bright yellow in the case of one characteristically untitled work from this inaugural year (Figure 1). The paintings are also framed, a detail that those familiar with Marioni’s mature work might find quite surprising.

Yet it is clear that multiple aspects of this period bothered Marioni. For one, the paintings were still fundamentally illusionistic, still predicated on a figure-ground relationship, however minimal. Within a few years, he would expunge all figuration and replace it with a pure, pungent materiality; this stage witnesses the emergence of Marioni’s signature drips, as well as his first investigations into constructing his paintings from multiple layers. In another untitled work, this from 1974 (Figure 2), we find in place of the shaft of light a densely and roughly painted cascade of very dark brown pigment running down the canvas’s center, layered multiple times until the color nears black. Over the next several years, Marioni (having now removed the picture frame entirely) widens this new band of pure paint until it surrounds the edges, in effect abolishing the figure-ground relationship by expanding the figure until it simply becomes the entire painted surface. Also essential here is Marioni’s new method of hanging the works from metal loops at roughly middle height on either framing edge, which has the effect of dramatically tilting the painting into the viewer’s space in an aggressive assertion of physicality. By the time we get to Painting 4-81 from 1981 (Figure 3; note the industrial impersonality of the new numerical titling system), this stage appears to have reached its culmination. Marioni had finally located his paintings as objects on the wall, objects that could “hold the wall.”4

Yet having achieved this, Marioni quickly discovered that, for a painting, simply being an object, however fully materially realized, was not enough to give it an identity as a painting; he had instead produced what he’s referred to as “painted objects.”5 Though they were strong works, and developmentally essential, Marioni had already perceived the next necessary step: Without, on the one hand, stripping away objectness, or, on the other, retreating back into the defunct pictorial strategies of figure and ground, he had to achieve what we might call paintingness. He would do this through the reintroduction of that with which he had begun: color.

Structure / Color

Marioni in essays and interviews often poses rhetorical questions to get us analytically deeper into the heart of the painting problems he is confronting. One of the most incisive comes from the Venetian Renaissance painter and theorist Paolo Pino, who inquired as to the fundamental difference between color in a jar and color in a painting.6 Color is already beautiful before it is applied to the canvas, his argument goes; for the painting to have a purpose, then, it must add something that the raw paint does not inherently contain. For Pino, the missing ingredient is the painting’s artful placement of the color among other colors in the overall composition.

Pino’s answer would seem to rule out the monochrome, which makes his original question all the more germane here. For single-color painting to be a worthwhile pursuit, it must somehow be doing something with color beyond the latter’s straightforward presentation, something that doesn’t have to do with compositional juxtaposition. What is it?

Color erupts back into Marioni’s paintings beginning around 1980—oranges, yellows, reds. But Marioni could see that he had to, in effect, answer Pino’s question. It would take five or more years of investigation for him to do so, and when his mature work begins to emerge in the late 1980s, the answer couldn’t be clearer.

The first step was the development of techniques to inflect and deepen the late-’70s “painted objects,” techniques that concerned themselves with the deliberate structuring of the paint and its relation to the support. He began building each painting as a “body color,” the basic format of which consisted of three layers: an opaque ground, a translucent middle color, and a transparent glaze (“the bones, the meat, and the skin”). Concurrent with this development was the emergence of Marioni’s other well-known techniques, such as allowing the paint to draw in from the edges of the support as it descends during the painting process and tapering the frames slightly toward the bottom to enhance this effect. Through this drawing in, he began subtly revealing some of the underlayers of each “body color,” calling attention to its composite structure. And he began rounding the lower edge of each stretcher so that the drips of paint would run off rather than gather into a line; he frequently lets these drips terminate well above the bottom of the support, creating another area in which underlayers can be perceived.7 All of these innovations had the effect of developing an internal boundary in the painting, one which did not re-create the figure-ground problem of the earliest efforts but which nonetheless restored a certain kind of interior depth that made these works more than solid surfaces, more than mere painted objects—a depth that made them paintings, “in the fullest and most exalted sense of the word,” as Michael Fried wrote in his review from this period.8 (You can find this hard-won internality on full display in Green Painting from 1992 (Figures 4 and 5), for instance. Note that he also abandoned the metal-loop hanging system in this stage, returning to hanging his paintings from the upper center and lessening, though not entirely eliminating, their tilt forward.)

The exploration of color was, of course, inextricable from these developments. Every decision about size, shape, layering, and structure that Marioni made for each painting was geared toward revealing something specific about whatever particular color he was working with. Marioni has written that this period emerged from his “recognition that color is the very reason for painting’s existence in the first place.”9 We find in these works too the full expression of his belief that each color has a size and shape most proper to it, most conducive to disclosing its specific personality, related to what he calls that color’s “archetype.” The relationship between color and archetype is part of what evokes a particular “feeling response” from the viewer. As he wrote in a 2002 essay:

It does seem to me there might be some form of an archetype to the colors of the painter’s palette, some structure that corresponds to our feeling response to color. Like earth, air, fire and water the colors of vision form structures that are characteristically distinct from one another and somehow intrinsic to each. If the creation of a painting is determined by our feeling response to the color and not just the concept of the artist, then the gestalt of the painting as an object should have some structural parallel to the archetype of its color…. This means, of course, that you cannot [make a blue painting] the same way you paint yellow, green or red.10

Accordingly, his red paintings tend to be more vertical to correspond to the body of the viewer, for example; yellow paintings tend to be square, relating them to our archetype for yellow, the sun. (Some of the paintings Marioni deems failures and destroys are works whose only evident defect is that they seem to be the wrong size and shape for their particular color.)We can already see the beginning of an answer to Pino’s question as it might be put to monochrome. The difference between color on a palette and color on a painting is that the painter’s specific decisions about structuring the painting—from the size and shape of the support to the particular building up of the paint itself—embody that color in a way that reveals something essential to it. As Marioni puts it, the painting’s entire “aesthetic value” is in nothing other than “the painted quality of the color within the gestalt of the painting as an object. That quality is dependent on how we materially structure the color.”11

Liquid / Light

The third phase of Marioni’s development, the phase in which he is still working today, begins in the mid-to-late 1990s. By this point he had gained mastery over his materials and was already painting major works which were bringing into equilibrium all the considerations he had spent the previous two decades wrestling with.

Yet there remained one element that had not yet received its due exploration, that element which is painting’s very condition of possibility: light.

Color, as Marioni regularly reminds us, is “divided light.” In terms of the sequence of events in the construction of a painting the painter first mixes pigment (the source of the paint’s color) into a medium (which has no coloristic properties unto itself; in Marioni’s case, the medium is acrylic). The resulting paint is then applied to the support, and the pigment, having been bound to the support by the medium, divides the light, i.e. “it holds some wavelengths and reflects back others. That light is revealed to us as color.”12

Though the chemical reality of this sequence is simple, its negotiation by the painter is anything but. Though any painted surface will necessarily divide light, it is the painter’s task to locate the light somewhere specific within the painting’s overall structure. “The game I play is the placement of the light in the painting,” Marioni has recently said. “Is it inside the painting? Is it on the surface? Does it come forward?”13

For Marioni, Rembrandt, as a varnish painter, enclosed his light inside the painting, strategically and sparingly allowing it to leak through in crucial passages. Monet, meanwhile, was known to bring the light to the very surface, and even beyond: Marioni describes a particular Monet at the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland whose water lilies, at certain times of day, produce a “perfume of blue that you walk through.” Marioni describes a similar effect in a yellow painting of his own, which is built on a foundation of pearlescent pigment whose silver quality retains no light and instead “pushes it all out.… So the light of the painting feels to be in front of the painting; it’s coming off the surface.”14 (2016’s Light, in the present exhibition, demonstrates a similar outward placement of light (Figures 6 & 7).)

The placement of the light is part pure color chemistry, to be sure, but it also depends on an acute awareness of the fact of the painting’s physical environment and the light present in that environment. This discovery relates this third stage of Marioni’s evolution to his first, in which he discovered the material reality of the painting as object; this stage too has been an acknowledgement of the painting as a physical object in space. “The perceptual context of a painting is the atmosphere of the environment in which it hangs,” Marioni writes, and this context, for the painter, is not an afterthought; it is, in fact, primary.15 As he puts it in a characteristic aphorism, “In the architecture of concrete painting, function follows light.”16

In speech and in practice, the term “liquid light” binds together the material and the immaterial; indeed, this binding is at the core of all painting. And it is the dialectical acknowledgment performed by the notion of liquid light that, finally, gives Marioni pride of place at this epochal moment in the history of his art form. If painting is in the midst of a transition “from pictorial representation to concrete actualization,” this actualization depends on the absolute recognition of painting’s most fundamental properties. Yet individual recognition is not enough; those properties must also be fused to one another in a relation of continuous interplay—of structural interdependence.17 This relation, when attempted, may strike us as paradoxical. Only the failure or success of the painting will tell us if it is that, or something more.

Notes

This originally appeared in Liquid Light: Joseph Marioni: Painter, Museum Wiesbaden/Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2018. Nonsite thanks Hengesbach Gallery for providing digital copies of the catalog photographs by Bernd Fickert.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.