photograph: James Welling, Front Door (2024)

MARIONI AT BRANDEIS

For his farewell exhibition as Director of the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis my former Princeton classmate the late Carl Belz — the best athlete in our class by no small margin — chose to mount a selection of forty paintings by the American painter Joseph Marioni. That was in 1998, Joseph was fifty-five, and his paintings were monochromes, a genre I was inclined against. (Actually that’s oversimple, the paintings were made by superimposing layers of translucent acrylic color, no two of which were the same, but in the end they bore plain titles, Red Painting, Blue Painting, etc. Hence monochromes.) I was unaware of Marioni’s work, and Carl was determined that I should see it. But he also knew how immovable I could be, so he worked out a strategy, what the French call une astuce, and made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: come to Brandeis and give a poetry reading in the exhibition. I went and read and Joseph was there; more to the point, I was totally convinced by the paintings, which thanks to Carl have turned out to be one of the basic references of my art-critical life to the present day. Joseph and I became friends, and I soon discovered that he had an exceptional “eye” — don’t believe anyone who tells you that no such thing exists. It does, and Joseph is the proof. I went on to write in praise of his paintings on several occasions, and every summer he spends a few days with us in the New York State countryside, much of it sitting on the deck and drinking everything in. Joseph is eighty now and has still to be recognized in this country as the master painter he indubitably is, one of the mysteries of the neoliberal art market I will never understand.

***

A LANDSCAPE BY RUISDAEL

In Memory of Joseph Marioni

There are landscape paintings in front of which it’s almost impossible to ignore the painter’s ambition to move you through the image — not just visually, from one parallel plane to another, as in classic pictures by Claude Lorrain, but as if physically, in quasi-bodily terms, following paths, climbing or descending hills, penetrating spaces of one sort or another, if necessary overcoming obstacles as you proceed. A case in point, confirmed by Joseph on the most recent of our summer excursions to the Clark Art Institute, is Jacob van Ruisdael’s Landscape with Bridge, Cattle, and Figures (ca. 1660), which I suggest to him, on the basis of a preliminary recon a few weeks before, amounts to an almost systematic demonstration of what could be done along these lines. Start with the curving path that enters the painting at the lower left, leading back to a sunlit stretch of rock just beyond which is a tiny figure of a bearded man in a wide-brimmed hat and a bright red shirt facing (walking?) toward the left and carrying a long staff– it’s not clear what he is doing but he ineluctably draws our gaze, in effect “placing” us in the painting’s middle distance. The movement then is toward the right, an extension of the low, bright rocky ridge, leading to a rushing stream with a drop in level flowing toward the picture-surface, in deliberate contrast to the into-the-painting impulse of the original path. And above the stream, commanding our attention, stretching from left to right on a rising trajectory is a narrow, spindly wooden bridge, made of boards laid side by side and supported from below by tall, not quite vertical wooden logs, a structure that hardly seems adequate to bear the two cows, assorted sheep and dogs, woman on a white horse, and two men one of whom may be carrying an infant who are about to traverse the bridge from upper right to lower left. (The woman gesturing toward the right against her forward motion, the bridge and its precariousness given further emphasis by the spatial separation of three partly overlapping bluffs topped with trees and vegetation starting at the right-hand edge of the canvas and leading the embodied eye once more into the painting’s depths.) And just beyond the left-hand end of the bridge there rises an irregular, mostly dead but still blossoming tree, stark against the massed white clouds in the afternoon sky — a surrogate of sorts, anchoring the composition as a whole. Finally, unexpectedly, at the bottom of the picture below the tree we are led to explore a hollowed out space strewn with worked blocks of stone that perhaps belonged to an earlier structure on that spot.

All this seems clear, indisputable. What is less clear is whether or not the viewer is also meant to feel a measure of frustration at being forced to remain outside the painting, merely looking on after all, and indeed whether or not the artificer of this carefully constructed scene experienced such frustration himself. I turn to Joseph and he is uncertain too. But perhaps that lack of certainty is the ultimate point.

***

CHARLEY ABDOO

The painter Joseph Marioni met him working in a hardware store and quickly saw that Charley had a range of skills that were being wasted. So he hired Charley to be his assistant, which meant spending days with Joseph in his shipshape studio-apartment on Eighth Avenue, sometimes sitting at a computer playing the market for them both (Charley did well) but more importantly taking care of multiple aspects of The Painter’s business — keeping track of supplies, making sure whatever sales there were went smoothly, arranging for the packing and shipping of paintings (a demanding chore), reminding Joseph of upcoming appointments, etc. All this without the least sense of strain or self-importance. And he had another virtue, the personal confidence not to resent the coming and going of Joseph’s friends. On the contrary, he recognized that the friends gave Joseph pleasure and he was glad about that. All the friends were aware of this and appreciated it. Charley was a black belt in Tae Kwan Do, a discipline he enjoyed, but although he looked fit his health was shaky, and one night back in his apartment he died suddenly — a huge loss for Joseph but also a source of sadness for friends of Joseph like me. In my case sadness enough to motivate a poem with no further end in view than to keep Charley’s image alive at least for a time.

***

OLYMPIA‘S CAT

Joseph Marioni, who had never seen Olympia before, testifies that he finds it a perfect painting. Not a judgment this painter bestows cheaply. He adds: “The only part I don’t understand is the black cat on the far right. I see that it is necessary but I don’t know why.” The cat, you will recall, has arched its back and appears to be bristling at the beholder, who notionally is the male visitor to the compactly attractive naked courtesan. I reply: there are two answers. The first is that the behavior of the cat introduces a note of instantaneousness — also of explicit aggression — into a composition which otherwise might be just a touch too classical for Manet’s purposes. (The actions of the cat supplementing Olympia’s steady, measuring gaze.) The second answer imagines the clever feline to be aware that right now Manet’s epoch-defining canvas is hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and as reacting preemptively against anyone who she suspects might be inclined to return them both to the funeste Musée d’Orsay.

***

THE LAST ARCHETYPE

Joseph Marioni emails to say that he has finally resolved his large green painting. The last Archetype has fallen — not fallen, exactly, rather it has yielded to The Painter’s uncompromising efforts. (The Archetype is Nature, though as always the painting is abstract, layers of translucent acrylic color filled with light.) Green presented special challenges, and Joseph’s satisfaction is palpable. In a few weeks he will visit, and we will sit outside on the deck, and in response to my questions he will explain the terms and stages of his victory, while our eyes are regaled by a world of greens.

***

ONE MORE POEM ABOUT JOSEPH MARIONI

June 6, 1943-Sept. 5, 2024

One more poem about Joseph Marioni, AKA The Painter, not planned or anticipated but thrust on me by Joseph’s sudden death four days ago. At eighty-one. In early July he visited Ruth and me at our “barn” in Buskirk, NY as he had done every summer for years. He would drive up from the City, bringing his own snacks for breakfast, and stay three nights. Every year we would go together to the Clark Art Institute, the last few times with particular focus in the Inness room — an underrated figure, his touch and vision utterly unique, fully the equal of the major nineteenth-century European landscapists except for Constable at his best. Setting Cezanne apart as a special case. Not surprisingly, Joseph shared my admiration for Inness’s lifelong affinity for the color green, the chief concern of The Painter’s monochrome operations in a recent series of ambitious works (see “The Last Archetype”). In fact the next afternoon as we sat on the deck idly watching clouds and birds Joseph brought out for my instruction a foot-long piece of canvas on which he had placed in sequence patches of the different layers of translucent acrylic paint that he had applied with a roller (as always, grasping the staff with both hands) in his latest large painting, the basic idea being that after each layer of one or another green there followed a layer of white intended to insure that the cumulative superimposition of greens would appear pushed forward and indeed filled with light. (“Liquid light” was one of his happiest thoughts.) All this on unprimed high-grade linen canvas stretched across a just barely non-rectangular wooden support that took Joseph weeks to carpenter from scratch, the almost indiscernible departure from verticality of the two side edges matching the tendency of the rolled-on paint to draw slightly inward in its descent. (Joseph’s art was nothing if not exact.) As I say elsewhere, I never understood — I never will understand — why Joseph’s radiant creations were not targets of acquisition for blue-chip dealers seeking the privilege of representing him and making a small fortune by doing so. But the paintings however ravishing were simply too serious for the current art world and no fraction of a small fortune came Joseph’s way. By the end he was reconciled to this. His project, as he explained later that afternoon, was to make one masterpiece each year for the next ten years and try to place it appropriately. The term masterpiece seems to me entirely apt. But he was wrong about the ten years.

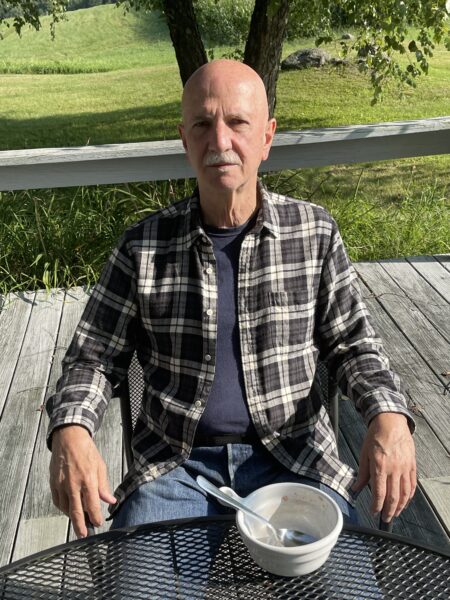

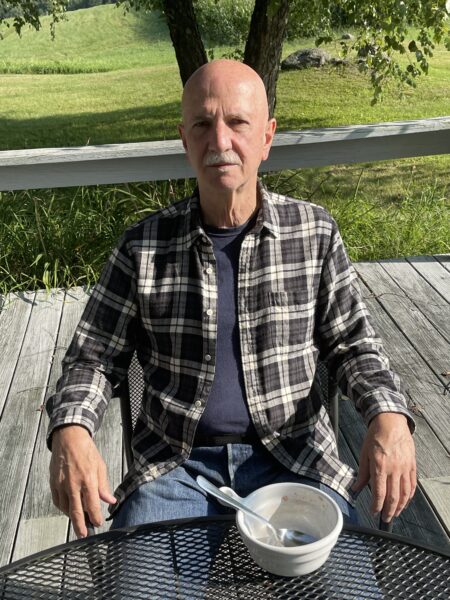

photograph: Michael Fried (2024)

The above poems will appear in The Edge of the Table: A Book of Prose Poems, to be published by ERIS in 2025.

photograph: James Welling, Front Door (2024)

MARIONI AT BRANDEIS

For his farewell exhibition as Director of the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis my former Princeton classmate the late Carl Belz — the best athlete in our class by no small margin — chose to mount a selection of forty paintings by the American painter Joseph Marioni. That was in 1998, Joseph was fifty-five, and his paintings were monochromes, a genre I was inclined against. (Actually that’s oversimple, the paintings were made by superimposing layers of translucent acrylic color, no two of which were the same, but in the end they bore plain titles, Red Painting, Blue Painting, etc. Hence monochromes.) I was unaware of Marioni’s work, and Carl was determined that I should see it. But he also knew how immovable I could be, so he worked out a strategy, what the French call une astuce, and made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: come to Brandeis and give a poetry reading in the exhibition. I went and read and Joseph was there; more to the point, I was totally convinced by the paintings, which thanks to Carl have turned out to be one of the basic references of my art-critical life to the present day. Joseph and I became friends, and I soon discovered that he had an exceptional “eye” — don’t believe anyone who tells you that no such thing exists. It does, and Joseph is the proof. I went on to write in praise of his paintings on several occasions, and every summer he spends a few days with us in the New York State countryside, much of it sitting on the deck and drinking everything in. Joseph is eighty now and has still to be recognized in this country as the master painter he indubitably is, one of the mysteries of the neoliberal art market I will never understand.

***

A LANDSCAPE BY RUISDAEL

In Memory of Joseph Marioni

There are landscape paintings in front of which it’s almost impossible to ignore the painter’s ambition to move you through the image — not just visually, from one parallel plane to another, as in classic pictures by Claude Lorrain, but as if physically, in quasi-bodily terms, following paths, climbing or descending hills, penetrating spaces of one sort or another, if necessary overcoming obstacles as you proceed. A case in point, confirmed by Joseph on the most recent of our summer excursions to the Clark Art Institute, is Jacob van Ruisdael’s Landscape with Bridge, Cattle, and Figures (ca. 1660), which I suggest to him, on the basis of a preliminary recon a few weeks before, amounts to an almost systematic demonstration of what could be done along these lines. Start with the curving path that enters the painting at the lower left, leading back to a sunlit stretch of rock just beyond which is a tiny figure of a bearded man in a wide-brimmed hat and a bright red shirt facing (walking?) toward the left and carrying a long staff– it’s not clear what he is doing but he ineluctably draws our gaze, in effect “placing” us in the painting’s middle distance. The movement then is toward the right, an extension of the low, bright rocky ridge, leading to a rushing stream with a drop in level flowing toward the picture-surface, in deliberate contrast to the into-the-painting impulse of the original path. And above the stream, commanding our attention, stretching from left to right on a rising trajectory is a narrow, spindly wooden bridge, made of boards laid side by side and supported from below by tall, not quite vertical wooden logs, a structure that hardly seems adequate to bear the two cows, assorted sheep and dogs, woman on a white horse, and two men one of whom may be carrying an infant who are about to traverse the bridge from upper right to lower left. (The woman gesturing toward the right against her forward motion, the bridge and its precariousness given further emphasis by the spatial separation of three partly overlapping bluffs topped with trees and vegetation starting at the right-hand edge of the canvas and leading the embodied eye once more into the painting’s depths.) And just beyond the left-hand end of the bridge there rises an irregular, mostly dead but still blossoming tree, stark against the massed white clouds in the afternoon sky — a surrogate of sorts, anchoring the composition as a whole. Finally, unexpectedly, at the bottom of the picture below the tree we are led to explore a hollowed out space strewn with worked blocks of stone that perhaps belonged to an earlier structure on that spot.

All this seems clear, indisputable. What is less clear is whether or not the viewer is also meant to feel a measure of frustration at being forced to remain outside the painting, merely looking on after all, and indeed whether or not the artificer of this carefully constructed scene experienced such frustration himself. I turn to Joseph and he is uncertain too. But perhaps that lack of certainty is the ultimate point.

***

CHARLEY ABDOO

The painter Joseph Marioni met him working in a hardware store and quickly saw that Charley had a range of skills that were being wasted. So he hired Charley to be his assistant, which meant spending days with Joseph in his shipshape studio-apartment on Eighth Avenue, sometimes sitting at a computer playing the market for them both (Charley did well) but more importantly taking care of multiple aspects of The Painter’s business — keeping track of supplies, making sure whatever sales there were went smoothly, arranging for the packing and shipping of paintings (a demanding chore), reminding Joseph of upcoming appointments, etc. All this without the least sense of strain or self-importance. And he had another virtue, the personal confidence not to resent the coming and going of Joseph’s friends. On the contrary, he recognized that the friends gave Joseph pleasure and he was glad about that. All the friends were aware of this and appreciated it. Charley was a black belt in Tae Kwan Do, a discipline he enjoyed, but although he looked fit his health was shaky, and one night back in his apartment he died suddenly — a huge loss for Joseph but also a source of sadness for friends of Joseph like me. In my case sadness enough to motivate a poem with no further end in view than to keep Charley’s image alive at least for a time.

***

OLYMPIA‘S CAT

Joseph Marioni, who had never seen Olympia before, testifies that he finds it a perfect painting. Not a judgment this painter bestows cheaply. He adds: “The only part I don’t understand is the black cat on the far right. I see that it is necessary but I don’t know why.” The cat, you will recall, has arched its back and appears to be bristling at the beholder, who notionally is the male visitor to the compactly attractive naked courtesan. I reply: there are two answers. The first is that the behavior of the cat introduces a note of instantaneousness — also of explicit aggression — into a composition which otherwise might be just a touch too classical for Manet’s purposes. (The actions of the cat supplementing Olympia’s steady, measuring gaze.) The second answer imagines the clever feline to be aware that right now Manet’s epoch-defining canvas is hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and as reacting preemptively against anyone who she suspects might be inclined to return them both to the funeste Musée d’Orsay.

***

THE LAST ARCHETYPE

Joseph Marioni emails to say that he has finally resolved his large green painting. The last Archetype has fallen — not fallen, exactly, rather it has yielded to The Painter’s uncompromising efforts. (The Archetype is Nature, though as always the painting is abstract, layers of translucent acrylic color filled with light.) Green presented special challenges, and Joseph’s satisfaction is palpable. In a few weeks he will visit, and we will sit outside on the deck, and in response to my questions he will explain the terms and stages of his victory, while our eyes are regaled by a world of greens.

***

ONE MORE POEM ABOUT JOSEPH MARIONI

June 6, 1943-Sept. 5, 2024

One more poem about Joseph Marioni, AKA The Painter, not planned or anticipated but thrust on me by Joseph’s sudden death four days ago. At eighty-one. In early July he visited Ruth and me at our “barn” in Buskirk, NY as he had done every summer for years. He would drive up from the City, bringing his own snacks for breakfast, and stay three nights. Every year we would go together to the Clark Art Institute, the last few times with particular focus in the Inness room — an underrated figure, his touch and vision utterly unique, fully the equal of the major nineteenth-century European landscapists except for Constable at his best. Setting Cezanne apart as a special case. Not surprisingly, Joseph shared my admiration for Inness’s lifelong affinity for the color green, the chief concern of The Painter’s monochrome operations in a recent series of ambitious works (see “The Last Archetype”). In fact the next afternoon as we sat on the deck idly watching clouds and birds Joseph brought out for my instruction a foot-long piece of canvas on which he had placed in sequence patches of the different layers of translucent acrylic paint that he had applied with a roller (as always, grasping the staff with both hands) in his latest large painting, the basic idea being that after each layer of one or another green there followed a layer of white intended to insure that the cumulative superimposition of greens would appear pushed forward and indeed filled with light. (“Liquid light” was one of his happiest thoughts.) All this on unprimed high-grade linen canvas stretched across a just barely non-rectangular wooden support that took Joseph weeks to carpenter from scratch, the almost indiscernible departure from verticality of the two side edges matching the tendency of the rolled-on paint to draw slightly inward in its descent. (Joseph’s art was nothing if not exact.) As I say elsewhere, I never understood — I never will understand — why Joseph’s radiant creations were not targets of acquisition for blue-chip dealers seeking the privilege of representing him and making a small fortune by doing so. But the paintings however ravishing were simply too serious for the current art world and no fraction of a small fortune came Joseph’s way. By the end he was reconciled to this. His project, as he explained later that afternoon, was to make one masterpiece each year for the next ten years and try to place it appropriately. The term masterpiece seems to me entirely apt. But he was wrong about the ten years.

photograph: Michael Fried (2024)

The above poems will appear in The Edge of the Table: A Book of Prose Poems, to be published by ERIS in 2025.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.