The present argument is about a tension between the thingly- or object-character of the work of art and understanding. My claim is that this tension manifests itself in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), the work of both James Agee and Walker Evans, albeit in different ways. Each, I will argue, finds ways to act out this tension by emphasizing or metaphorically representing the thingliness of the work and opposing it to meaning. Evans and Agee’s remarkable classic is an artifact of the thirties—the photographs are all from 1936, and the text was largely written between 1936 and 1938—in more ways than one. It will be part of my claim that its formal and thematic means of metaphorically working out the tension between thingliness and intelligibility parallel an economic theme that is very much of its moment. The economic theme—the way the book’s ontological reflection appears metaphorically as a reflection on the nature of money and the economics of tenantry—goes directly to questions that were vital to discourse on the United States’s evolving monetary system under the New Deal. More on all of that as the argument proceeds. The larger stakes and a fuller reasoning for the remarkable connection between artistic problems and economic ones will be more fully elaborated in a book project of which the present argument is just one part. In a fuller exposition, the opposition between the radical views of Agee and Evans and the less critical commitments of, say, Frank Capra and his collaborator Robert Riskin would spell out the nature and the value of Agee and Evans’s point of view more fully. Here, my aim is to make it clear how these tensions and the parallel between them work in Walker Evans’s photographs.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is the delayed outcome of an assignment Fortune magazine gave James Agee in 1936. Fortune asked Agee to take a photographer to Alabama to live among and report on the situation of white tenant farmers. Agee requested that Walker Evans accompany him, and the Resettlement Administration (later part of the Farm Security Administration), for which Evans worked at the time, agreed to lend him to Fortune. The two stayed with three tenant families during the summer of 1936. Fortune rejected Agee’s piece and released the rights to him. Between 1936 and 1938, Agee labored to turn the essay into a book and found a publisher. The publisher made publication contingent on certain revisions, not all of which Agee was willing to make. Agee eventually made an agreement with Houghton Mifflin, which published the book in 1941. Its sales were very disappointing; Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was remaindered. Two decades later, after Agee’s sudden and premature death in 1955 and after a novel he was working on was edited (or completed) by David McDowell, published as A Death in the Family (1957), and won a Pulitzer Prize, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was republished in a second edition with a revised selection of photographs and became a modern classic.

Much writing on the book deals with the ethical issues surrounding documentary. The founder, so to speak, of modern writing on documentary, William Stott, in his Documentary Expression and Thirties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), devoted a great deal of discussion to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Agee’s own concerns about the ethics of documentary, which fill the text, have made it a fertile subject for further ethical reflection.1 As for Evans’s photography, his gift for a dispassionate, neutral, or even sardonic tone is well remarked. (More on that shortly.) I will not challenge that general verdict. My point will be to press it toward something more specific, both as a critical and historical thesis concerning his work on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. In order to make my project clearer and to suggest something about the communal or joint nature of Evans and Agee’s undertaking, I want to begin by proposing a thesis about how James Agee reflected on the dual natures of the work of art and money or goods.

I

The crux of the reflection is this: each one has a durable, even thingly, character opposed to another nature, which comes into being as the other is consumed. The durable or thingly side of a book is the bound volume, which sits on the table or the shelf. The other being of the book appears in reading, in understanding. A publisher later claimed that Agee considered asking that Let Us Now Praise Famous Men be printed on the cheapest paper available so that, ideally, it would crumble as one finished reading it. It’s hearsay and kind of silly, but I think the story says something. It’s as if the thingly character of the book and its intelligible nature opposed one another in Agee’s view.

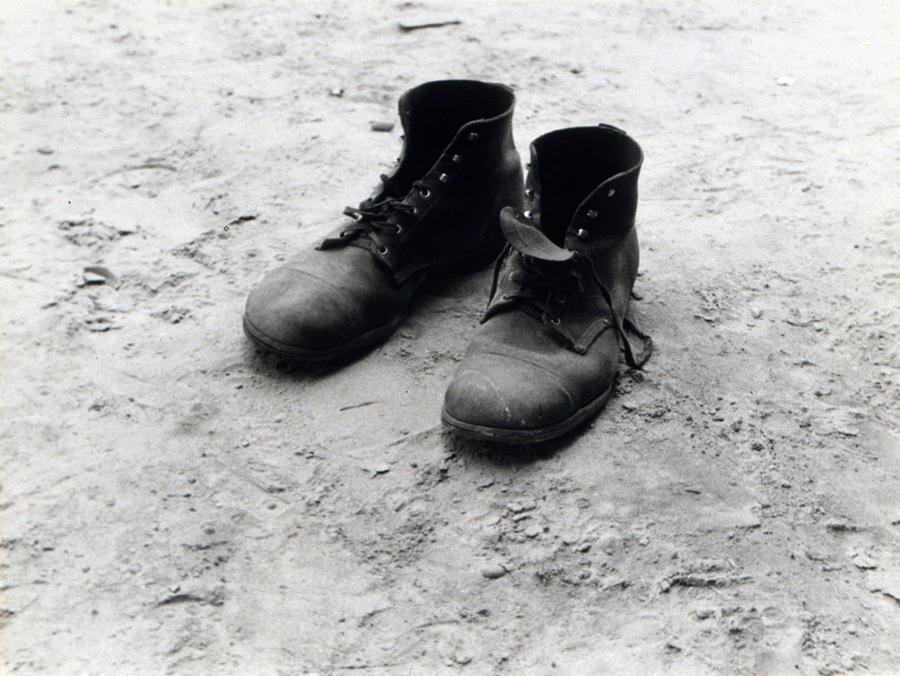

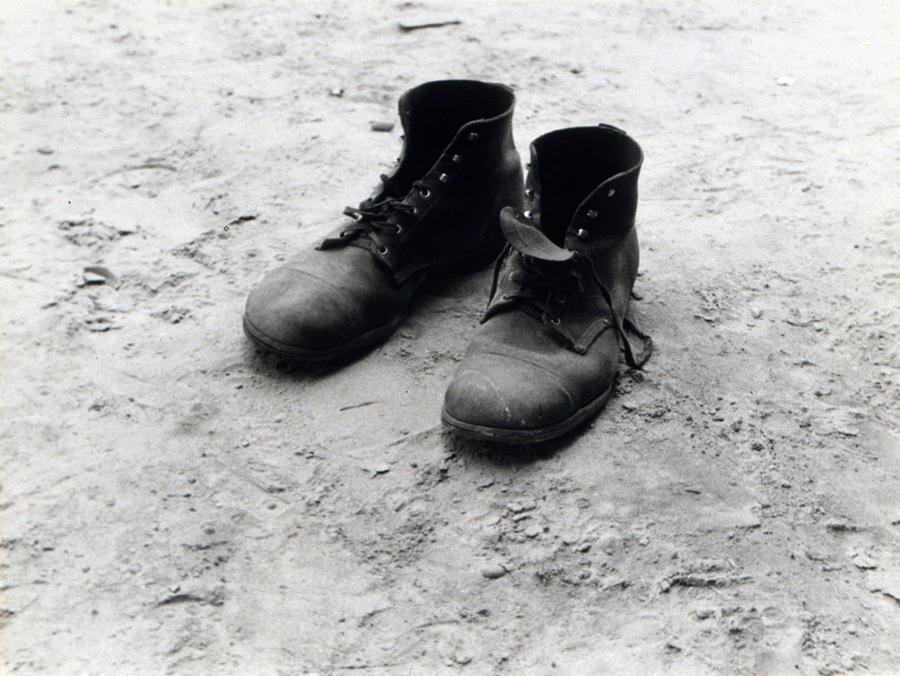

Similarly to the fantasy of the self-consuming book, a consumer good, such as a work shoe, has a thingly character. But its material being must be compromised, diminished, consumed in the course of its life. In the end, its uppers crack, its soles wear through, it is used up. If it has been used up productively, it will have paid for itself. (That is the point of work shoes.) Likewise, the loan that purchased it can be retired, amortized, paid off. In the case of, say, an asset on a balance sheet, its value can be progressively diminished—we say depreciated—according to a schedule that diminishes its value progressively over its expected useful life, in keeping with accounting principles, until no value is left. This is nothing new to us. We speak of a debt as if it were something heavy, which we carry with difficulty—a debt burden—and which hobbled or hindered us, as a crippling debt or a debt to be chipped away at. As eccentric as Agee’s reported request might be, the parallel with debt is clear. In some way, consuming a text overcomes or renders its material being beside the point, at least in a certain sense. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men uses this parallel throughout.

Indeed, the book begins with a story about these processes of using up in which the using up fails. In a section early in the book titled “At the Forks,” Agee discusses an encounter with some farmers, clients of the New Deal, who had accepted from the government advances of seed and fertilizer and a young steer.2 The farmers were broke and were unable to raise a crop or repay the loan. Among them, Agee encounters an older man who says only “Awnk, awnk” (PFM, 35).

This group could not raise their crops or repay their loan because they were given a sick steer and sterile, overused land, and the seed and fertilizer had been too late to begin growing before the heat made the new plants die (PFM, 35). What remained, besides the dying crop and steer and the tools, etc., was their debt. The invincible debt seems to me like a representation of the bad and durable quality of their advances from the government, just the way an incomprehensible utterance remains mere sound or marks.

A premise of tenant farming is that obligation begins the annual cycle. Seed, fertilizer, land, rations, and all other necessities are received from the landlord. The season’s work aims at using up the purchases in order to make the money necessary to repay the obligation—for all practical purposes, a debt.3 In the case of failure—should the crops die or fail to bring enough income—the loan remains like an unintelligible mark.

The older member of the farm family, who only says awnk, acts out the materiality of language. Apart from articulating the nonsense syllable he repeats, his mouth gnashes the fingers of his left hand and grapples with a piece of cornbread, making “grinding, passionate noises … in his throat.” Agee compares the man’s head to “a piece of heavy machinery.” His miscarriage of language is as material as fingers and cornbread; it is for grinding, not speaking. He gives Agee a “rolled farm magazine” (PFM, 36). Considering Agee’s purpose in visiting Hale County, the magazine seems to play a reflexive role—a cautionary example of a journalist’s language as a mere thing. Its passage from the older man to Agee is not the sharing or confiding of meaning; rather, it stands for the failure of writing to realize such possibilities, a failure figured in its form—rolled, as opposed to open, as a magazine might be opened to a page for reading.

This literary and economic failure stands in opposition to other self-reflexive representations of art elsewhere in the book. Farmers’ shoes make a fascinating example of success. Agee says that as they are worn in, they begin to resemble the farmer’s foot. Some farmers, he says, cut their shoes up to provide ventilation and comfort. The result, Agee says, is something like art. But the wearing in and the cutting up accelerate the shoes’ wearing out. Again, the shoes become representations of the farmer’s foot or works of artistic carving as they approach the end of their useful lives. Once thus fully depreciated, a farmer’s shoes, Agee explains, can be given to the farmer’s wife (PFM, 269–71). Like the book printed on cheap paper, the work’s successful transmission to an addressee is the culmination of its wearing out. Agee says similar things about overalls and, indeed, about the cotton the farmers bring to the gin to be processed and made into bales and into chits representing amounts of money with which to settle debts.

Far from an idiosyncratic feeling about materiality, Agee’s reflection on the dual nature of the work of art seems important and true. Without its thingly nature, the work cannot convey anything; in understanding, however, the work’s thingly nature is overcome, which is to say, rendered external to the meaning or understanding it has enabled. (After you have read a book, the fate of the copy you read is unimportant. Should a page be torn out and destroyed—or if the book crumbles in your hands—the damage will not affect how you have understood what you read.) In this, the work of art is like the material goods in the farmers’ lives that are used up in production.

Debt may represent the failure of the farmers in “At the Forks” or represent the way the New Deal failed them. This debt may, as I have been suggesting, even represent the materiality of language that has not been overcome in understanding. But debt, like materiality, is both something to be overcome and something deeply necessary. Debt is the other way of naming money. Marriner Eccles, who was Governor of the Federal Reserve during the New Deal, understood the desire of those who, facing tough times, approved of a sound monetary policy and a strong dollar. But he saw the paradox: he explained that the lion’s share of the money supply was debt. The bulk of the money we do our business with is not printed by the Treasury; rather, it is created in banks as debt. When the federal government spends money, it does not call down to the Treasury for a new stack of notes. The federal government, Eccles explained, creates a debit with a bank in the Federal Reserve system and thereby creates new money. “The banks can create and destroy money. Bank credit is money. It’s the money we do most of our business with, not with the currency we usually think of as money.”4 If banks stop creating debt, they stop creating the money we need. And when banks, facing a landscape of business and farm failures, sought to maintain liquidity to defend themselves against panics and runs, they were contracting the money supply and thus causing the failures that made the business atmosphere so bleak. “What was to be done,” Eccles asked in his memoirs, “when men on the farms and in the cities, who needed each other’s goods, were stranded on opposite river banks without the consumer purchasing power by which they could navigate a crossing for trading?”5 Debt, in this picture, is not in any simple way an impediment or a burden; it is the medium of movement, of circulation, of exchange.

Eccles explains that debt also is money—the creation of debt opens the space in which money can circulate. Debt represents the farmers’ failure in “At the Forks.” But only because they were unable to gain purchase on the system of exchange that would permit them to retire it. Agee used that unrepayable debt to figure sounds that could not effect the creation of meaning—which is to say, sounds that refused to become language and to be used up in understanding. But debt could also succeed, and Agee represented the possibility of debt opening a space for commerce and consumption. The consumer goods, like shoes and overalls, and money and debt figure the work of art or literature for Agee only as they are used up. They convey meaning only as they vanish in opening up the space of production and consumption, which is to say, in a space where debt and money disappear together. Otherwise, they stand for sound as against language.

Ultimately, then, my argument is that, in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee is committed to an understanding of money such as Eccles advances—one in which a Federal Reserve empowered, as part of the course of monetary policy and in support of banks, to create money by creating debits at its member banks—and that commitment doubles, metaphorically, his view of the ontology of the work of art, according to which the work of art is created by the conjuring of a world of meaning and the reciprocal establishment of an object. In their creation, the work of art and its thingly substrate are as deeply related as money and debt under the New Deal regime and, in similar ways, necessarily related and necessarily opposed to each other.

II

Walker Evans’s work in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men embodies a view closely related to Agee’s. We can begin to see it in his way of making a theme of framing.6 One photograph shows a fenced garden (fig. 1). The fence, which touches the framing edge at right and left, has fallen conspicuously, opening the garden in precisely the way a fence is meant to enclose it. A photograph’s framing edge could be understood the same way—it is the frame that makes the photograph function pictorially, as an arrangement of pictorial elements within its typically rectangular boundaries. A photograph is something else, too, though, since its very nature depends on the world casting its light onto the photosensitive emulsion. In this sense, it is more like an object—a frozen reflection or shadow—than a picture. If this indexicality defines the photograph’s thingly nature, it is nonetheless vital to its pictorial nature since the picture the photographer composes is supplied by its indexicality. As in the case of the farmer’s shoes on Agee’s account of them, the photograph’s thingly character is the condition of its overcoming by its pictorial nature. I think the photograph of the failed fence reflects on this fact about the photograph as a means of pictorial expression.

Figure 1. Walker Evans, [Bud Fields’ garden, Hale County, Alabama], 1936.

Figure 1. Walker Evans, [Bud Fields’ garden, Hale County, Alabama], 1936.

To expand on Evans’s relation to the dual nature of the work of art, let’s consider Evans’s interest in Gustave Flaubert, which predates his interest in photography. After leaving college, Evans traveled to Paris, where he wanted to study literature and become a writer in the mold of Flaubert. Recently, Svetlana Alpers has compared Evans’s photography to Flaubert’s style indirect libre. Her claim, which I will not pursue further, is that Flaubert’s famous use of reported speech and thought and his use of the imperfect tense produced a sense of impersonality combined with the presence of the passage of time in the reader’s encounter with objects in the fictional world of the text that finds its analogue in Evans’s direct views of his subjects—an effect so like looking at a thing itself as to make Evans’s voice, his presence, seem to disappear. “Detachment, description, and sense of things in time are at issue.”7

I would like to consider further dimensions of Evans’s affinity for Flaubert’s style indirect libre. A text that exists in a set of fragments tells the story of events in 1932. The fragments refer either to “the trouble of 1932” or “the revolution of 1932” in their opening sentences. The latter draft tells us that during the revolution:

people from the country came into the city. There were houses in the city where the inhabitants had things like food coming in regular rhythm by habit and by law; things to eat coming into the back door, and at ends of periods a bill sent and the bill paid or something reasonably done, and the food rhythm kept up.

Referring to the country folk who enter the cities, Evans writes of “things increasing wrong with their stomachs and heads” and of “certain abnormal ‘conditions’ in various stages … taking place inside their bodies.” Evans’s prose is remarkable. I would point out two qualities: first, despite being a series of short, choppy phrases, the long sentence is held together by prepositional phrases and conjunctions. Second, the ordinary crossings for trading of which Eccles wrote appear in Evans’s text as arcane rituals that, taken together, amount to what he calls “the food rhythm.” Bills sent and paid, habit and law, something reasonably done. Starvation and exhaustion represented as “things increasing wrong” or “abnormal ‘conditions’” (the scarequotes are Evans’s). It seems Evans’s aim was to offer the reader a glimpse of the strangeness of this uneven distribution of food and suffering and the arcane but determining role of law and custom and money in it, while simultaneously making these features of contemporary life strange.

It is precisely these two features—a thingly solidity of prose, achieved through the use of conjunctions and short phrases, and an impressionistic reduction of the reader’s synthetic understanding of familiar processes to their analytic bases at the limits of direct observation—that Marcel Proust identifies in Flaubert’s prose. Proust makes these remarks in an essay that Alpers cites and which Flaubert published a few years before Evans arrived in France.8 Evans may have known it. At any rate, several years later, he appears to have put its lessons to use. In this little passage, we can see Evans’s understanding of the duality of the work of art. If, for Proust’s Flaubert, prose is to be made heavy and ugly by mortaring together short phrases with conjunctions and adverbial phrases—that’s Proust’s judgment and Proust’s masonry metaphor, not mine—the same appears to be true for Evans.9 And if, for Proust’s Flaubert, this mortared prose serves paradoxically to return to the impression—to pare the familiar ways of the world down to phenomena—then Evans seems similarly committed to transforming this solid wall of prose into an effect of untutored seeing.

The force of Evans’s impressionism is to make strange the failure of the crossing of which Eccles wrote—the failure of the market economy to enable a crossing for goods from one riverbank to the other. The as-it-were mortared heaviness of Evans’s impressionism reflects the difficulty of passage and enacts the obstinacy and strangeness of the impasse. A doubling in its effect similar to the parallel we saw in Agee between language as matter and economic failure.

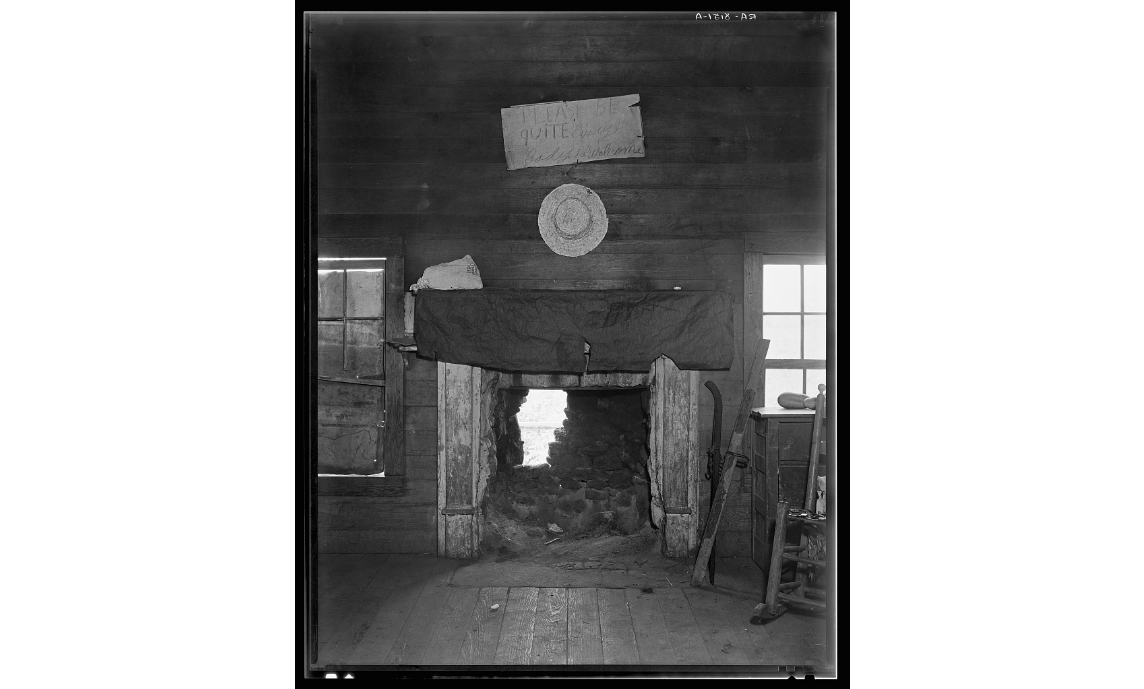

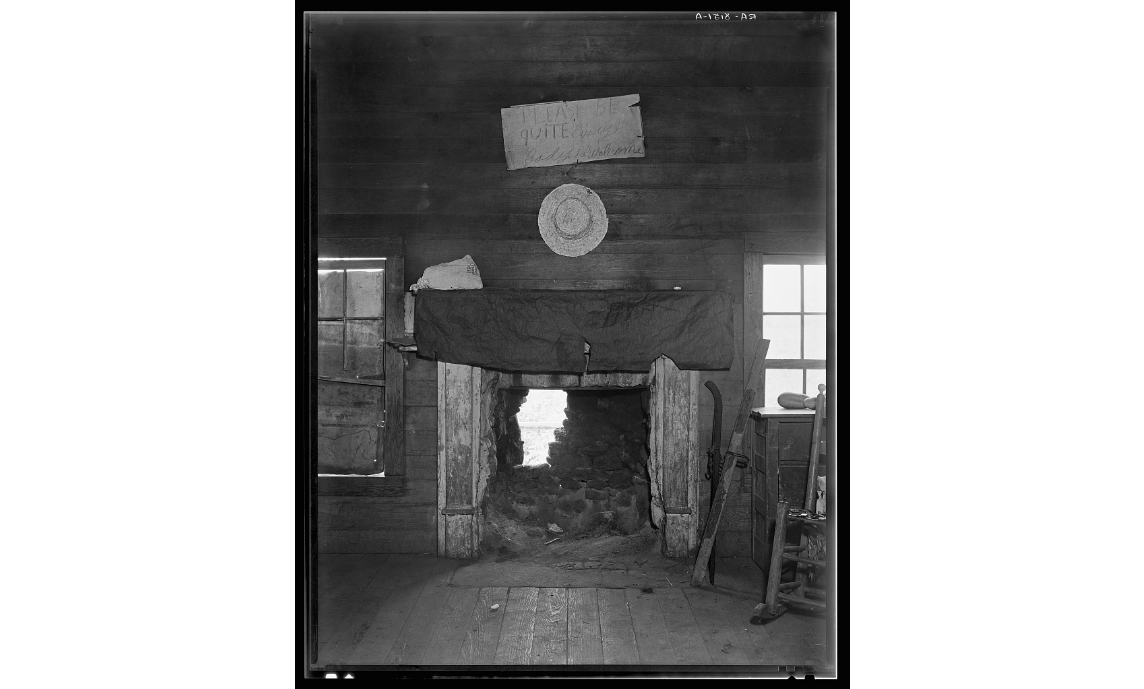

Let’s look at another of Evans’s photographs (fig. 2). This mantlepiece is centered in a wall. Above it, the handwritten sign, with the mixture of pitiless objectivity and pathos of its misspelling and duality of voices (block capitals versus cursive), relays the world of the undereducated tenants like unattributed reported speech. The window at left resists rather than transmits the view outdoors. The wall’s boards parallel the picture plane, extending from the upper framing edge and spanning the print’s width through its top third, like the sky in a landscape, but solid. The scene repeats the materiality of its support, except for the broken firebox, which opens like the fallen fence to the world at large. It’s as if the voice of the farmers and the scene of their living must contend with dumb matter to penetrate this space.

A pair of shoes stands abandoned in another photograph (fig. 3). They seem isolated, framed as they are by a generous margin of plain dirt. That is to say, one is given nothing to see but them—so much so that their isolation feels like an elaborate frame. The lack of a horizon or a view that extends to any distant feature, or even a clear indication that the ground itself recedes from the beholder, makes the space seem airless—less like space than like a container. The shoes irresistibly imply their owner and the world in which they are put to use. One is tempted to think of Agee’s analysis of work shoes—to imagine their consumption, whether by transformation into a filigree of their owner’s making or by the action of sweat and heat into a print of his feet. But the photographed shoes resonate with pictorial art, too, in a more traditional way. One thinks of Van Gogh’s paintings of boots, which had recently been on view in New York at the Museum of Modern Art.10 The Levy Gallery, which showed Evans’s work, had also shown this work by René Magritte (fig. 4). In all likelihood, Evans and Agee had seen it. Perhaps they had read the little text written by the Belgian surrealist Paul Nougé on the cover of the show’s catalogue. In it, Nougé asked:

But how shall we give the object such a virtue of fascination, such a charm? Here the fundamental operation would seem to be isolation: in isolation the charm of an object is in direct proportion to its triviality …. Further: the subversive value of an isolated object is in direct proportion to the intimacy which it has had with our body ….

The method itself consists in isolating the object by breaking off its ties with the rest of the world in a more or less brutal or in a more or less insidious manner. We may cut off a hand and place it on a table, or we may paint the image of a cut off hand on the wall.

We may isolate by using a frame or by using a knife ….11

Nougé is clearly attuned to the dialectical relation between framing and continuity—the space that surrounds an object both isolates it and embeds it in the world—and the tension between the way a frame isolates an object and, on the other hand, the way a cut, a fence, a tear, a break, or disuse, isolates a represented object even within a frame.

In 1936, for the tenants especially, everything depended on finding a way for someone to put his feet in the boots, to wear them out in effecting a crossing between those who had the capacity to produce and those who needed to consume. One way to see this task would be to imagine it as coming to terms with the dialectical oppositions I have argued were central to Agee’s and Evans’s enterprises—namely, to find a way to represent the overcoming of the opposition between the boots as things and the boots as elements of a productive enterprise, or of the opposition between money as the power to effect the crossing and money as the obverse face of obdurate debt. To translate this set of oppositions into artistic form—into a reflection on the ontology of art, even—was at the heart of Agee and Evans’s achievement in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Notes

Gudger has no home, no land, no mule; none of the more important farming implements. He must get all these of his landlord. Boles, for his share of the corn and cotton, also advances him rations money during four months of the year, March through June, and his fertilizer.

Gudger pays him back with his labor and with the labor of his family.

At the end of the season he pays him back further: with half his corn; with half his cotton; with half his cottonseed. Out of his own half of these crops he also pays him back the rations money, plus interest, and his share of the fertilizer, plus interest, and such other debts, plus interest, as he may have incurred.

What is left, once doctors’ bills and other debts have been deducted, is his year’s earnings. (PFM, 115–16.)

A substantially similar arrangement obtained, according to Agee, between Boles and the other two families, the Woods and Ricketts families, operate on slightly better terms, since they own some of their own implements and mules. And Agee concedes that under many arrangements, rations are provided in kind or through company stores, rather than under an allowance. But I take the details of the arrangement—and the accuracy of Agee’s understanding—to be subordinate to his aim to represent the tenants’ year’s work as an effort to retire an obligation with money, and therefore as a struggle to liquidate a debt. My thanks to Adrienne Petty for sharing her expertise in the practice of tenantry.↑

Michael Fried offers an account of Flaubert’s prose that surpasses Proust’s in nuance, detail, and breadth, but which is nevertheless in harmony with Proust and with which I take my own remarks to be in harmony. See Michael Fried, Flaubert’s “Gueuloir”: On Madame Bovary and Salammbô (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012) and Michael Fried, “Chapter One of L’Education sentimentale as a Work of Writing,” in French Suite: A Book of Essays (London: Reaktion Books, 2022), 226–47.↑

The present argument is about a tension between the thingly- or object-character of the work of art and understanding. My claim is that this tension manifests itself in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), the work of both James Agee and Walker Evans, albeit in different ways. Each, I will argue, finds ways to act out this tension by emphasizing or metaphorically representing the thingliness of the work and opposing it to meaning. Evans and Agee’s remarkable classic is an artifact of the thirties—the photographs are all from 1936, and the text was largely written between 1936 and 1938—in more ways than one. It will be part of my claim that its formal and thematic means of metaphorically working out the tension between thingliness and intelligibility parallel an economic theme that is very much of its moment. The economic theme—the way the book’s ontological reflection appears metaphorically as a reflection on the nature of money and the economics of tenantry—goes directly to questions that were vital to discourse on the United States’s evolving monetary system under the New Deal. More on all of that as the argument proceeds. The larger stakes and a fuller reasoning for the remarkable connection between artistic problems and economic ones will be more fully elaborated in a book project of which the present argument is just one part. In a fuller exposition, the opposition between the radical views of Agee and Evans and the less critical commitments of, say, Frank Capra and his collaborator Robert Riskin would spell out the nature and the value of Agee and Evans’s point of view more fully. Here, my aim is to make it clear how these tensions and the parallel between them work in Walker Evans’s photographs.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is the delayed outcome of an assignment Fortune magazine gave James Agee in 1936. Fortune asked Agee to take a photographer to Alabama to live among and report on the situation of white tenant farmers. Agee requested that Walker Evans accompany him, and the Resettlement Administration (later part of the Farm Security Administration), for which Evans worked at the time, agreed to lend him to Fortune. The two stayed with three tenant families during the summer of 1936. Fortune rejected Agee’s piece and released the rights to him. Between 1936 and 1938, Agee labored to turn the essay into a book and found a publisher. The publisher made publication contingent on certain revisions, not all of which Agee was willing to make. Agee eventually made an agreement with Houghton Mifflin, which published the book in 1941. Its sales were very disappointing; Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was remaindered. Two decades later, after Agee’s sudden and premature death in 1955 and after a novel he was working on was edited (or completed) by David McDowell, published as A Death in the Family (1957), and won a Pulitzer Prize, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was republished in a second edition with a revised selection of photographs and became a modern classic.

Much writing on the book deals with the ethical issues surrounding documentary. The founder, so to speak, of modern writing on documentary, William Stott, in his Documentary Expression and Thirties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), devoted a great deal of discussion to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Agee’s own concerns about the ethics of documentary, which fill the text, have made it a fertile subject for further ethical reflection.1 As for Evans’s photography, his gift for a dispassionate, neutral, or even sardonic tone is well remarked. (More on that shortly.) I will not challenge that general verdict. My point will be to press it toward something more specific, both as a critical and historical thesis concerning his work on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. In order to make my project clearer and to suggest something about the communal or joint nature of Evans and Agee’s undertaking, I want to begin by proposing a thesis about how James Agee reflected on the dual natures of the work of art and money or goods.

I

The crux of the reflection is this: each one has a durable, even thingly, character opposed to another nature, which comes into being as the other is consumed. The durable or thingly side of a book is the bound volume, which sits on the table or the shelf. The other being of the book appears in reading, in understanding. A publisher later claimed that Agee considered asking that Let Us Now Praise Famous Men be printed on the cheapest paper available so that, ideally, it would crumble as one finished reading it. It’s hearsay and kind of silly, but I think the story says something. It’s as if the thingly character of the book and its intelligible nature opposed one another in Agee’s view.

Similarly to the fantasy of the self-consuming book, a consumer good, such as a work shoe, has a thingly character. But its material being must be compromised, diminished, consumed in the course of its life. In the end, its uppers crack, its soles wear through, it is used up. If it has been used up productively, it will have paid for itself. (That is the point of work shoes.) Likewise, the loan that purchased it can be retired, amortized, paid off. In the case of, say, an asset on a balance sheet, its value can be progressively diminished—we say depreciated—according to a schedule that diminishes its value progressively over its expected useful life, in keeping with accounting principles, until no value is left. This is nothing new to us. We speak of a debt as if it were something heavy, which we carry with difficulty—a debt burden—and which hobbled or hindered us, as a crippling debt or a debt to be chipped away at. As eccentric as Agee’s reported request might be, the parallel with debt is clear. In some way, consuming a text overcomes or renders its material being beside the point, at least in a certain sense. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men uses this parallel throughout.

Indeed, the book begins with a story about these processes of using up in which the using up fails. In a section early in the book titled “At the Forks,” Agee discusses an encounter with some farmers, clients of the New Deal, who had accepted from the government advances of seed and fertilizer and a young steer.2 The farmers were broke and were unable to raise a crop or repay the loan. Among them, Agee encounters an older man who says only “Awnk, awnk” (PFM, 35).

This group could not raise their crops or repay their loan because they were given a sick steer and sterile, overused land, and the seed and fertilizer had been too late to begin growing before the heat made the new plants die (PFM, 35). What remained, besides the dying crop and steer and the tools, etc., was their debt. The invincible debt seems to me like a representation of the bad and durable quality of their advances from the government, just the way an incomprehensible utterance remains mere sound or marks.

A premise of tenant farming is that obligation begins the annual cycle. Seed, fertilizer, land, rations, and all other necessities are received from the landlord. The season’s work aims at using up the purchases in order to make the money necessary to repay the obligation—for all practical purposes, a debt.3 In the case of failure—should the crops die or fail to bring enough income—the loan remains like an unintelligible mark.

The older member of the farm family, who only says awnk, acts out the materiality of language. Apart from articulating the nonsense syllable he repeats, his mouth gnashes the fingers of his left hand and grapples with a piece of cornbread, making “grinding, passionate noises … in his throat.” Agee compares the man’s head to “a piece of heavy machinery.” His miscarriage of language is as material as fingers and cornbread; it is for grinding, not speaking. He gives Agee a “rolled farm magazine” (PFM, 36). Considering Agee’s purpose in visiting Hale County, the magazine seems to play a reflexive role—a cautionary example of a journalist’s language as a mere thing. Its passage from the older man to Agee is not the sharing or confiding of meaning; rather, it stands for the failure of writing to realize such possibilities, a failure figured in its form—rolled, as opposed to open, as a magazine might be opened to a page for reading.

This literary and economic failure stands in opposition to other self-reflexive representations of art elsewhere in the book. Farmers’ shoes make a fascinating example of success. Agee says that as they are worn in, they begin to resemble the farmer’s foot. Some farmers, he says, cut their shoes up to provide ventilation and comfort. The result, Agee says, is something like art. But the wearing in and the cutting up accelerate the shoes’ wearing out. Again, the shoes become representations of the farmer’s foot or works of artistic carving as they approach the end of their useful lives. Once thus fully depreciated, a farmer’s shoes, Agee explains, can be given to the farmer’s wife (PFM, 269–71). Like the book printed on cheap paper, the work’s successful transmission to an addressee is the culmination of its wearing out. Agee says similar things about overalls and, indeed, about the cotton the farmers bring to the gin to be processed and made into bales and into chits representing amounts of money with which to settle debts.

Far from an idiosyncratic feeling about materiality, Agee’s reflection on the dual nature of the work of art seems important and true. Without its thingly nature, the work cannot convey anything; in understanding, however, the work’s thingly nature is overcome, which is to say, rendered external to the meaning or understanding it has enabled. (After you have read a book, the fate of the copy you read is unimportant. Should a page be torn out and destroyed—or if the book crumbles in your hands—the damage will not affect how you have understood what you read.) In this, the work of art is like the material goods in the farmers’ lives that are used up in production.

Debt may represent the failure of the farmers in “At the Forks” or represent the way the New Deal failed them. This debt may, as I have been suggesting, even represent the materiality of language that has not been overcome in understanding. But debt, like materiality, is both something to be overcome and something deeply necessary. Debt is the other way of naming money. Marriner Eccles, who was Governor of the Federal Reserve during the New Deal, understood the desire of those who, facing tough times, approved of a sound monetary policy and a strong dollar. But he saw the paradox: he explained that the lion’s share of the money supply was debt. The bulk of the money we do our business with is not printed by the Treasury; rather, it is created in banks as debt. When the federal government spends money, it does not call down to the Treasury for a new stack of notes. The federal government, Eccles explained, creates a debit with a bank in the Federal Reserve system and thereby creates new money. “The banks can create and destroy money. Bank credit is money. It’s the money we do most of our business with, not with the currency we usually think of as money.”4 If banks stop creating debt, they stop creating the money we need. And when banks, facing a landscape of business and farm failures, sought to maintain liquidity to defend themselves against panics and runs, they were contracting the money supply and thus causing the failures that made the business atmosphere so bleak. “What was to be done,” Eccles asked in his memoirs, “when men on the farms and in the cities, who needed each other’s goods, were stranded on opposite river banks without the consumer purchasing power by which they could navigate a crossing for trading?”5 Debt, in this picture, is not in any simple way an impediment or a burden; it is the medium of movement, of circulation, of exchange.

Eccles explains that debt also is money—the creation of debt opens the space in which money can circulate. Debt represents the farmers’ failure in “At the Forks.” But only because they were unable to gain purchase on the system of exchange that would permit them to retire it. Agee used that unrepayable debt to figure sounds that could not effect the creation of meaning—which is to say, sounds that refused to become language and to be used up in understanding. But debt could also succeed, and Agee represented the possibility of debt opening a space for commerce and consumption. The consumer goods, like shoes and overalls, and money and debt figure the work of art or literature for Agee only as they are used up. They convey meaning only as they vanish in opening up the space of production and consumption, which is to say, in a space where debt and money disappear together. Otherwise, they stand for sound as against language.

Ultimately, then, my argument is that, in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee is committed to an understanding of money such as Eccles advances—one in which a Federal Reserve empowered, as part of the course of monetary policy and in support of banks, to create money by creating debits at its member banks—and that commitment doubles, metaphorically, his view of the ontology of the work of art, according to which the work of art is created by the conjuring of a world of meaning and the reciprocal establishment of an object. In their creation, the work of art and its thingly substrate are as deeply related as money and debt under the New Deal regime and, in similar ways, necessarily related and necessarily opposed to each other.

II

Walker Evans’s work in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men embodies a view closely related to Agee’s. We can begin to see it in his way of making a theme of framing.6 One photograph shows a fenced garden (fig. 1). The fence, which touches the framing edge at right and left, has fallen conspicuously, opening the garden in precisely the way a fence is meant to enclose it. A photograph’s framing edge could be understood the same way—it is the frame that makes the photograph function pictorially, as an arrangement of pictorial elements within its typically rectangular boundaries. A photograph is something else, too, though, since its very nature depends on the world casting its light onto the photosensitive emulsion. In this sense, it is more like an object—a frozen reflection or shadow—than a picture. If this indexicality defines the photograph’s thingly nature, it is nonetheless vital to its pictorial nature since the picture the photographer composes is supplied by its indexicality. As in the case of the farmer’s shoes on Agee’s account of them, the photograph’s thingly character is the condition of its overcoming by its pictorial nature. I think the photograph of the failed fence reflects on this fact about the photograph as a means of pictorial expression.

Figure 1. Walker Evans, [Bud Fields’ garden, Hale County, Alabama], 1936.

Figure 1. Walker Evans, [Bud Fields’ garden, Hale County, Alabama], 1936.

To expand on Evans’s relation to the dual nature of the work of art, let’s consider Evans’s interest in Gustave Flaubert, which predates his interest in photography. After leaving college, Evans traveled to Paris, where he wanted to study literature and become a writer in the mold of Flaubert. Recently, Svetlana Alpers has compared Evans’s photography to Flaubert’s style indirect libre. Her claim, which I will not pursue further, is that Flaubert’s famous use of reported speech and thought and his use of the imperfect tense produced a sense of impersonality combined with the presence of the passage of time in the reader’s encounter with objects in the fictional world of the text that finds its analogue in Evans’s direct views of his subjects—an effect so like looking at a thing itself as to make Evans’s voice, his presence, seem to disappear. “Detachment, description, and sense of things in time are at issue.”7

I would like to consider further dimensions of Evans’s affinity for Flaubert’s style indirect libre. A text that exists in a set of fragments tells the story of events in 1932. The fragments refer either to “the trouble of 1932” or “the revolution of 1932” in their opening sentences. The latter draft tells us that during the revolution:

people from the country came into the city. There were houses in the city where the inhabitants had things like food coming in regular rhythm by habit and by law; things to eat coming into the back door, and at ends of periods a bill sent and the bill paid or something reasonably done, and the food rhythm kept up.

Referring to the country folk who enter the cities, Evans writes of “things increasing wrong with their stomachs and heads” and of “certain abnormal ‘conditions’ in various stages … taking place inside their bodies.” Evans’s prose is remarkable. I would point out two qualities: first, despite being a series of short, choppy phrases, the long sentence is held together by prepositional phrases and conjunctions. Second, the ordinary crossings for trading of which Eccles wrote appear in Evans’s text as arcane rituals that, taken together, amount to what he calls “the food rhythm.” Bills sent and paid, habit and law, something reasonably done. Starvation and exhaustion represented as “things increasing wrong” or “abnormal ‘conditions’” (the scarequotes are Evans’s). It seems Evans’s aim was to offer the reader a glimpse of the strangeness of this uneven distribution of food and suffering and the arcane but determining role of law and custom and money in it, while simultaneously making these features of contemporary life strange.

It is precisely these two features—a thingly solidity of prose, achieved through the use of conjunctions and short phrases, and an impressionistic reduction of the reader’s synthetic understanding of familiar processes to their analytic bases at the limits of direct observation—that Marcel Proust identifies in Flaubert’s prose. Proust makes these remarks in an essay that Alpers cites and which Flaubert published a few years before Evans arrived in France.8 Evans may have known it. At any rate, several years later, he appears to have put its lessons to use. In this little passage, we can see Evans’s understanding of the duality of the work of art. If, for Proust’s Flaubert, prose is to be made heavy and ugly by mortaring together short phrases with conjunctions and adverbial phrases—that’s Proust’s judgment and Proust’s masonry metaphor, not mine—the same appears to be true for Evans.9 And if, for Proust’s Flaubert, this mortared prose serves paradoxically to return to the impression—to pare the familiar ways of the world down to phenomena—then Evans seems similarly committed to transforming this solid wall of prose into an effect of untutored seeing.

The force of Evans’s impressionism is to make strange the failure of the crossing of which Eccles wrote—the failure of the market economy to enable a crossing for goods from one riverbank to the other. The as-it-were mortared heaviness of Evans’s impressionism reflects the difficulty of passage and enacts the obstinacy and strangeness of the impasse. A doubling in its effect similar to the parallel we saw in Agee between language as matter and economic failure.

Let’s look at another of Evans’s photographs (fig. 2). This mantlepiece is centered in a wall. Above it, the handwritten sign, with the mixture of pitiless objectivity and pathos of its misspelling and duality of voices (block capitals versus cursive), relays the world of the undereducated tenants like unattributed reported speech. The window at left resists rather than transmits the view outdoors. The wall’s boards parallel the picture plane, extending from the upper framing edge and spanning the print’s width through its top third, like the sky in a landscape, but solid. The scene repeats the materiality of its support, except for the broken firebox, which opens like the fallen fence to the world at large. It’s as if the voice of the farmers and the scene of their living must contend with dumb matter to penetrate this space.

A pair of shoes stands abandoned in another photograph (fig. 3). They seem isolated, framed as they are by a generous margin of plain dirt. That is to say, one is given nothing to see but them—so much so that their isolation feels like an elaborate frame. The lack of a horizon or a view that extends to any distant feature, or even a clear indication that the ground itself recedes from the beholder, makes the space seem airless—less like space than like a container. The shoes irresistibly imply their owner and the world in which they are put to use. One is tempted to think of Agee’s analysis of work shoes—to imagine their consumption, whether by transformation into a filigree of their owner’s making or by the action of sweat and heat into a print of his feet. But the photographed shoes resonate with pictorial art, too, in a more traditional way. One thinks of Van Gogh’s paintings of boots, which had recently been on view in New York at the Museum of Modern Art.10 The Levy Gallery, which showed Evans’s work, had also shown this work by René Magritte (fig. 4). In all likelihood, Evans and Agee had seen it. Perhaps they had read the little text written by the Belgian surrealist Paul Nougé on the cover of the show’s catalogue. In it, Nougé asked:

But how shall we give the object such a virtue of fascination, such a charm? Here the fundamental operation would seem to be isolation: in isolation the charm of an object is in direct proportion to its triviality …. Further: the subversive value of an isolated object is in direct proportion to the intimacy which it has had with our body ….

The method itself consists in isolating the object by breaking off its ties with the rest of the world in a more or less brutal or in a more or less insidious manner. We may cut off a hand and place it on a table, or we may paint the image of a cut off hand on the wall.

We may isolate by using a frame or by using a knife ….11

Nougé is clearly attuned to the dialectical relation between framing and continuity—the space that surrounds an object both isolates it and embeds it in the world—and the tension between the way a frame isolates an object and, on the other hand, the way a cut, a fence, a tear, a break, or disuse, isolates a represented object even within a frame.

In 1936, for the tenants especially, everything depended on finding a way for someone to put his feet in the boots, to wear them out in effecting a crossing between those who had the capacity to produce and those who needed to consume. One way to see this task would be to imagine it as coming to terms with the dialectical oppositions I have argued were central to Agee’s and Evans’s enterprises—namely, to find a way to represent the overcoming of the opposition between the boots as things and the boots as elements of a productive enterprise, or of the opposition between money as the power to effect the crossing and money as the obverse face of obdurate debt. To translate this set of oppositions into artistic form—into a reflection on the ontology of art, even—was at the heart of Agee and Evans’s achievement in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Notes

Gudger has no home, no land, no mule; none of the more important farming implements. He must get all these of his landlord. Boles, for his share of the corn and cotton, also advances him rations money during four months of the year, March through June, and his fertilizer.

Gudger pays him back with his labor and with the labor of his family.

At the end of the season he pays him back further: with half his corn; with half his cotton; with half his cottonseed. Out of his own half of these crops he also pays him back the rations money, plus interest, and his share of the fertilizer, plus interest, and such other debts, plus interest, as he may have incurred.

What is left, once doctors’ bills and other debts have been deducted, is his year’s earnings. (PFM, 115–16.)

A substantially similar arrangement obtained, according to Agee, between Boles and the other two families, the Woods and Ricketts families, operate on slightly better terms, since they own some of their own implements and mules. And Agee concedes that under many arrangements, rations are provided in kind or through company stores, rather than under an allowance. But I take the details of the arrangement—and the accuracy of Agee’s understanding—to be subordinate to his aim to represent the tenants’ year’s work as an effort to retire an obligation with money, and therefore as a struggle to liquidate a debt. My thanks to Adrienne Petty for sharing her expertise in the practice of tenantry.↑

Michael Fried offers an account of Flaubert’s prose that surpasses Proust’s in nuance, detail, and breadth, but which is nevertheless in harmony with Proust and with which I take my own remarks to be in harmony. See Michael Fried, Flaubert’s “Gueuloir”: On Madame Bovary and Salammbô (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012) and Michael Fried, “Chapter One of L’Education sentimentale as a Work of Writing,” in French Suite: A Book of Essays (London: Reaktion Books, 2022), 226–47.↑