Systems just aren’t made of bricks they’re mostly made of people. —Crass (1980)

In 2012, Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates participated in dOCUMENTA with 12 Ballads For Huguenot House, in which construction materials salvaged from an abandoned Chicago home were used to alter the space of a building in Kassel, Germany. The Kassel building had housed displaced French Protestants in the seventeenth century, while the Chicago building that supplied the materials, 6901 South Dorchester Avenue, formed a portion of Gates’ Dorchester Projects, a multi-building zone of arts and community activity located in Chicago’s largely low-income African American community of Woodlawn/Grand Crossing.1 Visually, the rough edges and visible seams of 12 Ballads combined the artistic precedent of Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural interventions, DIY riffs on mid-century modern design, and David Hammons’ allusive assemblage aesthetic. During the dOCUMENTA exhibition, the space hosted a series of events that included performances by Gates’ own zen gospel musical group, the Black Monks of Mississippi, as well as activities such as yoga classes and literary readings, tropes of ephemeral sociability familiar to anyone versed in recent relational and social art practices.2 In discussing the 12 Ballads work, many commentators focused on the aesthetic reworking of materials salvaged from a crumbling Chicago building, or on the parallel histories of forced migration that offered a point of overlap between French Huguenots and Chicago’s African American community.3 Thus Gates was understood, as he himself has described it, to work in the medium of “sculpture and mythmaking.”4

In the field, beyond the spaces of exhibition, Gates rehabs buildings in low-income African American urban areas of the Midwest and turns them into centers for arts and cultural programming. Gates’ activities generate artifacts for exhibition, but their primary focus is urban regeneration. Gates thus operates at the vanguard of recent socially engaged artistic situations, processes, and events that are intended to effect a change in the material circumstances of some of the participants or viewers: the social capital of artists is transferred to politically and economically marginalized populations. These contemporary practices ostensibly sidestep the art market, instead marshaling the resources of large, financially solvent institutions and foundations bound up in networks of global capital in order to materially benefit selected individuals or groups, in Gates’ case, African Americans living in low-income, urban communities in Chicago and other Rust Belt cities. While Gates and other artists rely partially upon art institutions, what marks these practices is that they draw upon a broader range of sources—e.g., elite universities’ investment in local communities, charitable foundations’ efforts to ameliorate social problems, community development corporations’ focus on alleviating urban poverty, federal tax credits intended to spur economic growth in low income neighborhoods—to effect a redistribution of wealth or access to power.

Art institutions certainly remain a necessary component of these “social practice” works, but only insomuch as they recast alleviation of social and economic inequality as cultural production.5 Though such practices have parallels to performance art, institutional critique, and relational aesthetics, these works are thus characterized by a parasitic relation to cultural, civic, and financial institutions. Commentators such as Gregory Sholette have seen a sort of parodic emulation in this mode of contemporary art practice, in which artist collectives offer “miniature replica[s] of institutional cohesion and legitimacy,” or “mockstitutions” which “seemingly fixed institutional participant[s]—the state, city, corporation, prison, museum, school, even the European Union”—feel compelled to support.6 However, Theaster Gates’ project is quite different, resembling instead what Michel Serres has described as the parasite: a figure who interrupts an existing circuit, producing disorder but also generating a different order.7 It is not simply that Gates creates fictitious institutions, or parodies extant institutions. Instead he institutionalizes informal arrangements. Gates himself has explained that, as he moved between “super formal” institutions, such as “museums, the gallery scene, [Chicago Department of] Cultural Affairs” and “super informal” institutions, such as “storefronts, or Walgreens, or Harold’s Chicken,”

I wanted to . . . call attention to . . . the life that is lived between them. And often, the really formal ones are outside of my neighborhood, and the informal ones are often in my neighborhood. So I also wanted to . . . have those two things collide in the way they collide in my life. . . . One of the byproducts of [my] projects is that there would be this kind of spatial collision, or this social collision, that really conflates how my life looks every day.8

Gates makes the ephemeral sociability of the black metropolis visible and concrete, institutionalizing it in the authority of archives and the durability of a newly aestheticized built environment, spaces that may themselves spur new diagonal exchanges across unseen social divides.9 More recently, Gates described his practice as “inventing daily publics and creating the conditions where a public might hang, and then it becomes real interesting when it’s territorial space like on the cusp of gentrification or on the cusp of the white University or on the cusp of an all-black neighborhood.”10 Thus, rather than locating the art of Gates’ practice in objects or performances, his work can more accurately be understood in terms of the new social arrays he generates, social arrays in which the cultural capital of the artist is transformed into concrete monetary investment. Even as Gates’ works materially benefit the neighborhoods in which they are located, Gates’ social position as artist makes his work intelligible as a cultural good available to be consumed by a broad public of art viewers.

In contemporary art, parasitic tactics work in several registers. The artist is often dependent upon, or parasitic upon, the financial and logistical support of various institutions in order to carry out large-scale socially engaged projects. He or she interrupts the flow of money aimed at the production or exhibition of art, diverting money and visibility toward people and communities typically absent from the art world.11 At the same time, art institutions themselves depend upon the artist to validate what might otherwise be half-baked forays into community politics or social services, or real estate ventures thinly disguised as such; this differentiates artistic parasitism from the “irreversible” and unidirectional flow described by Michel Serres. In the case of Gates, his entire practice hinges upon diverting wealth and access to power from extant channels to individuals and groups – typically poor, typically racially marked – otherwise cut off from such agency.12 But even as these “subjects” might be viewed as parasitic upon institutions, art institutions are in turn parasitic upon these subjects’ marginal social positions. To maintain their positions at the forefront of contemporary art—specifically the “social practice” strain—institutions depend upon a steady supply of people (again, typically poor and/or racially marked) with whom (or through whom) social practice can occur. As cultural institutions whose mandates typically involve some sort of community outreach, art institutions receive help validating their missions from social practice’s visible support for marginalized communities.

But this assertion raises the question: if this type of art is validated, or even constituted, by the extra-artistic, where does “the social” lie? Are these activities exemplary of an avant-garde aspiration to unite art and life, predicated upon a fundamental separation between the two realms? Is the social a ground against which art figures?13 Certainly, the very possibility of “socially engaged art” seems predicated on bridging a divide between distinct spheres of art and the social.14 There already exist substantial critiques of this model, both in terms of artistic autonomy and for social scientists who contend that, “Problems arise . . . when ‘social’ begins to mean a type of material, as if the adjective was roughly comparable to other terms like ‘wooden,’ ‘steely,’ ‘biological,’ ‘economical,’ ‘mental,’ ‘organizational,’ or ‘linguistic.’”15 But in addition to the general problem of isolating “the social” as “a kind of material or domain,” to which art can be opposed, there is an even starker divide at play with so-called social practice. For social practice, “the social” signifies “real people,” whom we might identify as the poor, the dispossessed, and/or the sexually or racially marked.16 Just as earlier avant-gardes sought to “expand what is considered artistic and to annex mundane, nonartistic matter,” recent socially-engaged practices take as their protagonists groups of people otherwise absent from the typical workings of the art world, thus absorbing nonartistic humans as artistic matter.17

Gates’ art is not, then, locatable in obvious artistic objects, or in his performances, but in networks of people, political agency, flows of investment; rather than sensual embodiments of marginalized lifeways, the objects that Gates creates or gathers are props, assisting him in staging the ephemeral sociability of the contemporary city. The following pages explore such networks in detail, showing how Gates has drawn upon the financial and political might of institutions such as large research universities, charitable foundations, and governments to act as real estate developer in low-income African American communities of the urban United States. But Gates should not be understood as an artist who performs the role of urbanist. Rather, his ability to generate funding and political will to accomplish projects depends upon his success at inhabiting the role of black contemporary artist. The intelligibility of Gates’ practice as art depends upon his carefully constructed self-presentation as a black contemporary artist, with his social practice works rendered artistic precisely by virtue of their creator’s social position.18 That is, as Michel Serres elaborates, the parasite “builds a new logic,” transmuting superstructure (art, social interactions) into infrastructure (money, property).19

From Gates’ earliest artworks, one can see the performance of blackness as a key problematic, beginning with “Japanese soul food” meals at the incipient Dorchester Projects around 2007. Gates was trained as a ceramicist, and many of his early projects addressed the shared significance of pottery in Japanese and African American cultures.20 In the mid-2000s, Gates invented the character of a Japanese potter, Shoji Yamaguchi, who settled in a Mississippi clay region in the 1960s and married an African American civil-rights activist. Supposedly, after the Yamaguchis’ death in the early 1990s, their son established an institute to continue their work melding Japanese and Southern African American aesthetics and cuisine. Building on this story, Gates threw ceramic plates for carefully-staged “Japanese soul food” meals, where diverse gatherings of people were invited to discuss “issues of race, political difference and inequalities of all sorts.”21

Similar practices include Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 1992 Untitled (Free), in which Tiravanija set up a kitchen at 303 Gallery in New York and served gallery goers free rice and Thai curry, and Liam Gillick’s documenta x installation Discussion Island (1997), which mythologized his Irish heritage by foregrounding a fabled Celtic mode of conflict resolution (carried out on the neutral ground of an island collaboratively maintained by various clans).22 Gates’ works not only mimic Tiravanija’s sensuous instantiation of the gift economy and Gillick’s use of quasi-architectural forms to shape behavior, but they draw upon a story rooted in ethnic identity, though in the case of Gates this was initially displaced onto the fictional character of the half-Black and half-Asian John Yamaguchi.23 Soon, Gates found his own position as an African American artist living in a poor neighborhood area on Chicago’s South Side would prove an even more potent narrative. By 2009, Gates was overtly addressing his own performance of blackness in works such as the lecture/performance, “To Be Pocket: Militaristic Effeminacy, The ‘Hood’ and Adorno’s Last Sermon, or, It’s Over When The Black Marching Band Goes Home.24 Moreover, Gates’ emphasis on semi-industrial, semi-artisanal production is linked, in his own accounts, to identity and biography. In addition to the importance of pottery in African American history, Gates has described his entry into art through work with his father in the construction industry, particularly tarring roofs.25 In performing the black contemporary artist, Gates thus draws upon a particular history of African American culture in relation to desires for authenticity in today’s art world.26 Yet despite similarly mobilizing identity to position his work within the contemporary art world, Gates’ practice contrasts to the “relational aesthetics” of Tiravanija and Gillick.

Where relational aesthetics may constitute ephemeral sociability as a temporary heterotopia within an art context, e.g., a museum, gallery, or international exhibition, Gates parasitically diverts resources from the contemporary art world to create new gathering spaces, new institutional configurations, that seek to alleviate a community’s lack. Gates’ work is thus more intelligible as “social practice art” or “service media art.”27 Early examples of this type of work came to wider attention with Mary Jane Jacobs’ 1993 Sculpture Chicago biennial, entitled “Culture in Action: New Public Art in Chicago.”28 For example, Chicago artist Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s participation in the biennial consisted of a collaboration among artists, a local community television network, and a teacher and students at a high school located in a predominantly Puerto Rican, low-income area of Chicago.29 The teenagers produced videos based in their own lives, which came together to form the multi-screen work Tele-Vecindario [Tele-Neighborhood] (1993), presented in vacant lots at a neighborhood block party during the biennial.30 The pertinent aspect of this project is, however, not so much its final presentation as the process by which it was produced, its blurring of lines between art practice and community organization. Another notable work in the 1993 Sculpture Chicago biennial was the work Flood, a storefront demonstration hydroponic garden organized by artist collective Haha and volunteers located in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago. In addition to producing and distributing garden vegetables and herbs to AIDS hospices and HIV-positive residents of Chicago, the group held bi-weekly meals and educational activities at the storefront.31 As with Mangano-Ovalle’s Tele-Neighborhood, what is notable about Haha’s practice is the difficulty of teasing out its artistic qualities as something distinct from its social or service character. Their presentations did deploy art-historical references. The television monitors of Manglano-Ovalle’s Tele-vecindario, for example, were placed on ersatz plinths formed of plastic milk crates, while the Haha storefront drew upon the precedent of Claes Oldenburg’s Store (1961) and updated it with a 1980s Soho gallery aesthetic with white shelves of catalogs and ephemera surrounding the central demonstration garden. However, ultimately, the artistic intelligibility of Tele-vecindario and Flood lay in the way that Manglano-Ovalle and Haha diverted the resources of the Sculpture Chicago Biennial and displaced the Biennial’s viewers to lower-income, largely non-white neighborhoods (Humboldt Park and Rogers Park)—and social collisions—they might otherwise not have encountered.

In a similar way, Theaster Gates’ practice can be understood to produce social collisions. His artworks assemble networks of people, including the visibly marginalized individuals who are both the subjects (the thematic focus) and objects (beneficiaries) of Gates’ projects, as well as the normative “art viewer” (wealthier, whiter) typically absent around Gates’ spaces on the South Side of Chicago. But his artworks are not simply assemblages of people. Instead, Gates constructs byzantine financial webs to support his spaces of ephemeral sociability (the street, the storefront, the community art center). These spaces act as artworks, while the sense of social purpose masks the extent of Gates’ engagement with contemporary capitalism. Parasitic practices thus act as a subset of social practice. They rely upon the mobile and deterritorialized processes of global capital, while offering justification through the corresponding “artificial, residual, archaic” reterritorializations, a form of self-essentializing as artistic branding which in turn generates financial and logistical support.32 A flow of money, from municipal tax credits to real estate investors, or wealthy philanthropists’ donations to the arts, or from tuition dollars and donations to the University of Chicago, is parasitically interrupted by Gates’ art practice, which finds relevance in today’s art world for its ability to mobilize tropes of minority culture intelligible within contemporary art discourse.

2. Sculptor + Mythmaker

Over the past decade, as Gates has transitioned from emerging to established artist, the nature of his practice has undergone a dramatic shift: from ceramics to architectonic structures, from small-scale events to large institutions. In one view, this move from studio to post-studio practice accompanies the increased availability of financial and logistical resources as Gates’ renown grew. The past decade of Gates’ practice can thus be seen to be oriented around a consistent set of aesthetic concerns, rooted in a rethinking of contemporary African American culture and a fresh take on the potential of art as an engine of urban development. However, this interpretation does not take into account the overall structure of Gates’ work, in that his practice consists of increasingly impressive networks of funding and logistical support, with artistic objects and cultural spaces acting as catalysts.

The Huguenot House of dOCUMENTA 13 existed, that is, as an aesthetic product within the larger ecosystem of Gates’ artistic practice: an extensive strategy to rehab buildings in low-income African American urban areas of the Midwest (Chicago, Omaha, St. Louis), and establish centers for arts and cultural programming. Most famously, for over a decade Gates has lived amidst the Dorchester Projects in the Grand Crossing neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, and it is from one of its component buildings that materials were removed for the Huguenot House work at dOCUMENTA.33 Gates was also instrumental in creating the Washington Park Arts Incubator, an arts and community center inaugurated in 2013 by the University of Chicago, where Gates is employed. In 2014, Gates’ practice expanded to encompass projects that directly address community needs, namely the large-scale residential project, Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative, in which a Chicago Housing Authority complex was transformed into mixed-income housing with an arts focus. Most recently, in 2015, Gates opened the Stony Island Arts Bank, in which an abandoned bank building was rehabbed to create a site for arts programming, as well as an archive centered on the history of black culture in the United States. Its collections include books from the shuttered Prairie Avenue Architecture Bookstore, records from the shuttered Dr. Wax music store, and the archives of famed African American magazines Ebony and Jet, as well as more somber items, such as the Cleveland gazebo where twelve-year-old Tamir Rice was killed by police gunshots in 2014.

Art objects do form an aspect of Gates’ larger practice, in that their sales have played a major role in generating funding for these urbanist or social practice projects. To help fund the Stony Island Arts Bank, Gates famously issued a limited edition of $5,000 “Bank Bonds” made – with a nod to Duchamp – from marble slabs that had formed partitions between urinals in the former bank’s restrooms. In a poetic flow of parasitism, wealth was made material in a 1920s bank building, while the 2000s saw these hunks of precious stone transmogrified back again into currency, which in turn supported the creative restoration of the building.34 However, these Bank Bonds raised only about $500,000 of the roughly $12 million budget for the Arts Bank; the rest came from investors benefitting from federal and state tax credits. Most of the funding, that is, came from the normal avenues for any low-income urban housing project. It is unlikely that Gates could have drawn together enough investment—whether from art sales or urban development tax credits—to accomplish large-scale urbanist projects like the Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative or the Stony Island Arts Bank without having established his bona fides as an artist. However, with regard to an art historical understanding of Gates’ art practice, his museum and gallery shows are largely beside the point.

The architectural detritus and assemblages that Gates exhibits, as well as the art criticism that has built up around his objects and performances, are simply ways of establishing Gates as artist. While the art historian Huey Copeland has described Gates’ objects as “set adrift from the economies that produced [them] in order that black life might thrive elsewhere,” they can also be understood as material manifestations of Gates’ cultural capital.35 In these aesthetic objects, Gates riffs on modernist painting (fire hoses as Frank Stella or Agnes Martin), post-Minimalist sculpture (chunks of rehabbed buildings evoke everything from Gordon Matta-Clark’s building cuts to Rachael Whiteread’s white casts), and African American cultural history (in the manner of David Hammons), a combination of references that support Gates’ strategic inhabitation of a social role as black contemporary artist. Gates’ object-based practice is, however, secondary to his primary aim: diverting the financial and social capital of large networked institutions to achieve ends that seem to evade conventional criteria of aesthetic judgment.

3. Properties and Profits

Gates’ work in real estate and urban development is propelled by his identification as an artist, which allows him to generate financial and logistical support for investment in the guise of cultural production. Undertaking his work as an artist rather than a developer also gives Gates access to a particular array of funding sources. The bulk of Gates’ projects have been carried out under the auspices of the Rebuild Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit established in 2010.36 Rebuild’s activities center on rehabbing buildings in African American communities of the Midwest for the purpose of housing community arts programming. Donations to the Rebuild Foundation are tax deductible, and it has received support from a laundry list of charitable foundations, such as the Pritzker Family Foundation and ArtPlace America, the latter of which is a collaboration among leading philanthropic foundations (including the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and Bloomberg Philanthropies) as well as several major financial institutions (Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, Citibank, Chase, MetLife, and Morgan Stanley).37 In addition to providing support for “general operating expenses,” these organizations have donated funds to specific projects undertaken by the Rebuild Foundation. Examples include the Hyde Park Art House in St. Louis, MO, which has housed urban design and music camps for middle schoolers, and the Carver Bank building in Omaha, NE, where exhibition and performance spaces, artist studios and a small cafe are managed and programmed by the Bemis Art Center.

The prototype for Gates’ broader production remains his multi-building Dorchester Projects complex in Chicago, which has included the Archive House—containing glass lantern slides from the University of Chicago Department of Art History, architectural books from the defunct Prairie Avenue Architecture Bookshop, and vinyl records saved from the demolished Dr. Wax music store, all collections moved to the Stony Island Arts Bank in 2015–and Black Cinema House, a film screening space dedicated to films of the African diaspora. The process of creating these spaces centered on acts of salvage. The cultural artifacts gathered within the Dorchester Projects, the repurposed construction materials that Gates used, and the structures of the buildings themselves have been salvaged from the wreckage of disinvestment in America’s black metropolises, exacerbated by the recent foreclosure crisis.38 Gates’ combination of art, artisanship, and a locally-rooted social mission has proved irresistible to philanthropists whose donations fund the Rebuild Foundation’s work.

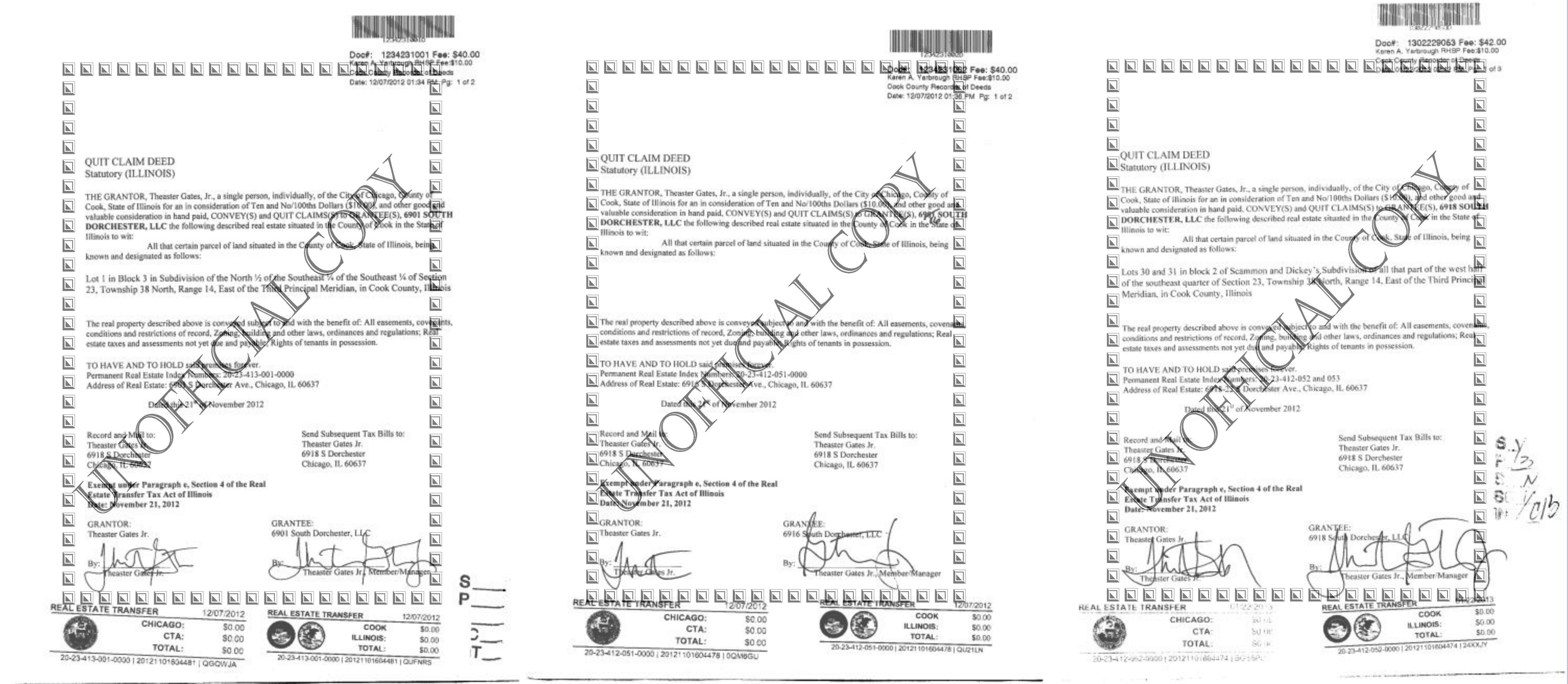

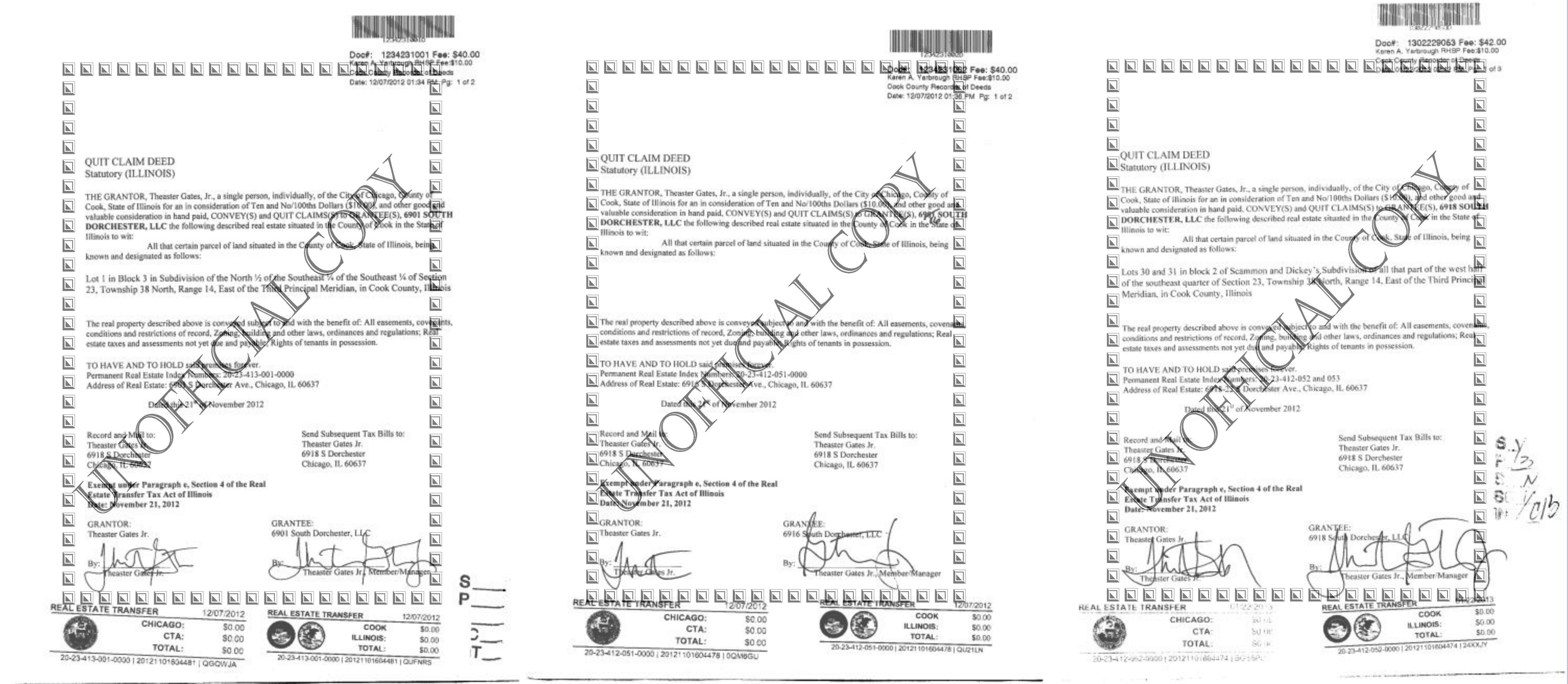

However, as the Rebuild Foundation admits, “Most of this work is actually carried out as a for-profit known as Dorchester Projects LLC. The buildings ARE NOT owned by Rebuild Foundation, but most of the wonderful things that happen in them are developed, organized, and managed by Rebuild Foundation.”39 In fact, in June 2011, the Rebuild Foundation received a $15,000 grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation specifically “To support the business plan and legal structure to separate for-profit from not-for-profit activities.”40 Subsequently, in 2012, Dorchester Projects LLC was renamed Theaster Gates Studios, LLC, while separate LLCs were created for each individual building of the Dorchester Projects, e.g., 6901 South Dorchester, LLC, 6916 South Dorchester, LLC, and 6918 South Dorchester. In late 2015, the Rebuild Foundation rebranded itself with a new website that diminished Gates’ visibility, and several buildings that had formerly comprised Gates’ Dorchester Projects were now reinterpreted as “Program Sites” of the Rebuild Foundation. Meanwhile, in the period between 2011 and the present, Gates established a number of other LLCs corresponding to additional buildings in the area. According to corporate filing documents, as of 2016 Theaster Gates was the Manager of LLCs associated with at least eight properties on the 6900 block of South Dorchester Avenue.41 That is, Gates manages these LLCs, and the LLCs are corporate owners of these properties.42

While Gates has not made public his intentions regarding these corporations, or his understanding of their function within his artistic practice, there are several notable aspects. For one, the conversion of these properties into LLCs parallels the displaced ownership and liquid assets that characterize the investment vehicles known as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).43 REIT companies assemble portfolios of income-producing properties, often office buildings or residential complexes. Individuals can buy shares in the REIT, and the income produced by the portfolio of properties—through sales or rents—is paid as dividends to shareholders, none of whom actually own any of the property in question. For Gates, the most immediate advantage of re-categorizing these properties as LLCs rather than as personally-owned properties is that—by relinquishing individual ownership—Gates enjoys limited liability for any lawsuits in connection with the properties.44 However, the structural parallel between Gates’ LLCs and REITs also has broader implications for the status of these properties as artworks. Unlike real estate parcels bundled into REITs, Gates’ LLCs (currently) fail to generate income. Yet each of Gates’ “artworks,” each property, can now be sold as a business. Or, as with REITs, individual shares or membership interests in these properties can be bought and sold, thus distributing gains and losses across a number of investors. Shares in Gates’ artworks can be bought and sold on the market. With the Stony Island Arts Bank Bank Bonds (2013), Gates has already thematized this financial structure in his work. However, as real estate rather than artworks, Gates’ properties may avoid the higher capital gains tax rate on art and collectibles (up to 28%), and be subject to the lower capital gains tax rate (15-20%) on investment income.45 With future sales of these artworks/properties, a museum or wealthy collector could “own,” or own a share of, the Archive House of Dorchester Projects, including its land, building, and possibly its archives.46 The sale might be accompanied by a detailed contract in the mode of sales of Conceptual Art, e.g., a Sol LeWitt wall drawing. Programming—and perhaps the archival collections—could remain the purview and property of Gates’ Rebuild Foundation, while the land, whether as real estate or as artwork, will continue to accrue value.

Gates’ practice is, then, a highly financialized endeavor which is even self-parasitic, in that money flows along a route through Gates’ various subsidiaries. The Rebuild Foundation, for example, depends upon donations from individuals as well as grants from private foundations, but an ostensibly virtuous cycle of philanthropic largesse and nonprofit social justice efforts is interrupted by the for-profit LLCs. Of course, Gates’ entire real estate endeavor is predicated upon an originary parasitism, as deindustrialization and suburbanization were paired with capital flight out of the urban U.S. from the 1960s onward.47 Moreover, in asserting control over swaths of these so-called blighted areas (a formal categorization which enables certain types of publicly funded investment), Gates performs a parodistic restatement of the post-Great Recession real estate market.48 Since 2008, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) have snapped up not only commercial properties, but also many single family homes, which they then rent to families and individuals dispossessed of their residences and lacking the income, credit, or downpayment to buy a home. Even as improving economic circumstances allowed many Americans to accumulate down payments in the years following the 2008 crash, many homes were bought and sold in all-cash sales by investors, often REITs. Gates’ practice adopts some of the same techniques as REIT investors, and Gates’ project has been similarly contingent upon depressed real estate values and the abandonment of structures in low income communities of America’s Rust Belt cities, especially African American neighborhoods.

By investing in real estate while performing the role of artist, Gates is able to combine for-profit and non-profit funding channels, enabled by an ethos of cultural production in support of community betterment. It is in this mix of public and private, profit-seeking and not-for-profit, that the parasitic nature of Gates’ work emerges. Gates’ practice should not, then, be understood simply as an altruistic form of arts activism or social practice art. Instead, Gates performs the social role of the artist—in a particularly Beuysian mode of artist as visionary, as shaman, as community activist, and which Gates himself has explicitly linked to his experiences in the black church—in order to carry out the radical reformation of, and reinvestment in, urban neighborhoods.49

4. Parasitism and the American University

Gates’ projects have often been carried out in conjunction with the University of Chicago, where he has worked since 2009, first as Director of Arts Programming Development and then, since 2011, as Director of Arts and Public Life. For example, the University of Chicago has poured over $1.3 million into the Washington Park Arts Incubator, a 1920s building that Gates rehabbed into a gallery, artist studios, and community space.50 This building sits just west of Washington Park, which had previously served as a buffer between the University and impoverished areas farther to the west. Located on Garfield Boulevard adjacent to the elevated train station closest to the University of Chicago, the Arts Incubator thus serves as the new face of the western entry to campus, and the university has been explicit about this area’s strategic importance. As the University of Chicago’s Vice President of the University’s Commercial Real Estate Operations (CREO) has explained, “Reviving the stretch of Garfield [Boulevard] between King Drive and Prairie Avenue is important to the university because the boulevard is the first thing many out-of-state and international students see when visiting campus.”51 But it is not only for cosmetic reasons that the University of Chicago has invested substantial sums to support Gates’ work in the urban areas surrounding the institution.

Even as the University of Chicago has faced criticism for aspects of its relationship to the surrounding neighborhoods, the institution’s support of Gates’ practice has led to considerable financial benefit as well as positive publicity. The ArtPlace Foundation—a joint project funded by a number of charitable foundations and corporate banks, and advised by various government entities—supported the Washington Park Arts Incubator with $400,000, given to and administered by the University of Chicago. And, in spring 2014 the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation awarded the University of Chicago a $3.5 million grant for “The Place Project,” to “build on pioneering work by Theaster Gates” to “expand and test a community development model that supports arts and culture to help transform communities and promote local growth and vibrancy.”52 Led by Gates and the university’s Art and Public Life initiative, the project’s brief was to “jump-start community-led development by bringing together artists, designers, urban planners and policy experts in cities such as Akron, Ohio; Detroit, and Gary, Ind.”53 The University of Chicago—itself a non-profit able to receive tax deductible donations—serves as an umbrella organization to receive and facilitate donations to Gates’ practice, and this relationship benefits the university as well. The artist is parasitic upon the institution in order to carry out projects, but the institution itself is parasitic upon the artist, since it reaps benefits from its association with the artist’s activities. Precisely such a parasitic relationship characterizes the subset of social practice art in which Gates is engaged, where investment to ameliorate social problems is channeled through artistic circuits.

Himself African American, and a resident of the predominantly African American, predominantly low-income neighborhood to the south of the University of Chicago, Gates can be seen as both a link between the university and the surrounding neighborhoods, and as a critical commentator on such involvement. One should question, however, whether Gates’ identity simply allows the University of Chicago to displace some of the anxiety facing its expansion into nearby low-income African American communities by positioning Gates as the public face of the university’s development. In supporting Gates’ “cultural development” projects, is the University of Chicago an arts patron, a community anchor, or is there another game at play?

Since the early 2000s, the University of Chicago has extended its reach southward, building new dormitories and a towering visual and performing arts center just beyond its symbolic southern boundary, the grassy Midway Plaisance between 60th and 61st Streets.54 More recently, the university turned its attention westward. Beginning around 2008, when this area became the focus of the City of Chicago’s bid for the 2016 Olympics, the University of Chicago purchased roughly ten acres next to Washington Park, which sits adjacent to the university and serves as a buffer between the school and impoverished areas to the west.55 Although the failure of Chicago’s Olympic bid briefly slowed real estate speculation in the area, the university soon set its sights on another goal.

In addition to making the areas surrounding the University of Chicago more desirable to students and the parents who typically pay their undergraduate tuition, the university was strategically marketing itself as a leading contender for the Obama Presidential Center.56 Parcels near Washington Park formed the core of one of the University of Chicago’s proposals for the Obama Presidential Center (though it is unlikely that this was a goal from the very start of the university’s flurry of purchases). And it is no accident that Gates, as the head of the University of Chicago’s Art and Public Life initiative, and as an African American property and business owner in the surrounding neighborhoods, served as the public face for the university’s incursions into Washington Park, Grand Crossing, and other low-income African American communities near the university. The University of Chicago’s support for Gates’ Arts Incubator was one prong in the institution’s efforts to demonstrate their commitment both to developing cultural institutions in the area, and to the African American community. As a promotional video created by the University of Chicago to support its proposal for the Obama Presidential Center demonstrates, the university bolstered its bid by emphasizing its location on Chicago’s South Side, and its link to the “rich cultural history” (i.e., African American history) of the area.57 Immediately after this statement, a statement about the South Side’s “great community leadership” offers a voiceover to a photograph of Theaster Gates alongside Chicago 3rd Ward Alderman Pat Dowell and University of Chicago President Robert J. Zimmer at the ribbon cutting for the Washington Park Arts Incubator. In May 2015, on the basis of its two proposals, one in Washington Park near Gates’ Arts Incubator, and the other in Jackson Park near Gates’ Dorchester Projects and Stony Island Arts Bank, the University of Chicago was awarded the Obama Presidential Center.

In July 2016, the location of the Obama Presidential Center was announced to be a parcel of land in Jackson Park, a Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted-designed lakefront park that was home to the 1893 World Columbian Exposition.58 The University of Chicago has long been invested in the nearby area, with several campus buildings on 60th and 61st Streets, albeit on the other side of the Metra commuter rail tracks from the Obama Presidential Center site. The Obama Presidential Center site is also mere blocks away from Theaster Gates’ Dorchester Projects and Stony Island Arts Bank, the latter of which is located just southeast of the southern edge of Jackson Park.59

While the University of Chicago was less explicit about the utility of the Jackson Park location prior to the site selection, it forms the core for a new $10.25 million funding initiative, a collaboration among Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation, the University of Chicago’s Place Lab and the City of Chicago.60 With $5 million from foundations including the The JPB Foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation, plus $5.25 million from local funders, the Reimagining the Civic Commons national initiative will invest in the neighborhood around the Stony Island Arts Bank. Neighborhood “assets,” such as a shuttered elementary school and vacant lots owned by the city, “will be transformed into vibrant civic spaces for public use.”61 Mere blocks away from the future home of the Obama Presidential Center, then, the University of Chicago will be involved in this large-scale remaking of an entire urban neighborhood, and Theaster Gates’ Stony Island Arts Bank is considered the “flagship” or “first active asset” of this project.62

5. Social Alchemy: Transforming Capital

Not only does the Stony Island Arts Bank, a highly visible, large-scale project in which Gates foregrounded African American cultural production, form a crucial backdrop for the Obama Presidential Center, it also plays a key role in Gates’ overall project. With the Stony Island Arts Bank, there are formal shifts in Gates’ practice, on the level of aesthetics as well as institutionality. The Stony Island Arts Bank is not a private home turned community space, like much of Dorchester Projects, but a former conduit of financial flows remade into a cultural institution. Where Dorchester Projects buildings were initially open for events or ad hoc, Stony Island Arts Bank has regular hours and staffing. Materially, the crumbling wood and brick residential buildings of the Dorchester Projects have given way to high-ceilinged spaces of former commercial buildings made from durable materials like stone and marble. At the same time, the aesthetic of Gates’ work has changed, with professional architectural and design partners replacing the DIY aesthetic of his earlier works. In the early years, the Dorchester Projects were described as “rehabbed . . . with spare elegance, using recycled stone and salvaged wood. When you walk in you feel transported, like you’ve landed in a Zen temple.”63 In contrast, even though the Arts Bank rehab left bits of crumbling wall and cracked ceiling, reflecting the lack of official efforts to preserve institutions in minority communities, the Classical revival temple-style exterior is more closely related to traditional conceptions of what a fine arts museum should look like.64 Like the Washington Park Arts Incubator, the Stony Island Arts Bank thus adapted a building that already signaled institutional longevity and cultural import through scale, architectural style, and durable materials.65

As a durable institution, the Stony Island Arts Bank enfolds and valorizes as art the ephemeral sociability of the black metropolis, which Gates has previously organized more around commerce. The original building of Dorchester Projects, for example, was a former candy store, while Gates thematized the shoeshine stand in his 2010 Whitney Biennial installation. Gates also cited Walgreens and Harold’s Chicken as “super informal” institutions that he contrasted to the “super formal” institutions of the Chicago art world, i.e., museums, the gallery scene, and the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events.66 These commercial spaces, while they may be formal for the corporations that run them, are places of informal institutionality for the South Side of Chicago, where non-profits (e.g., museums) and government departments seem largely absent. With the Stony Island Arts Bank, Gates creates a formal institution in which African America’s faltering or failed businesses (Ebony, Jet, Dr. Wax) and the pre-archival ephemera of contemporary African American life are presented as cultural patrimony, both aesthetically (in the marble walls and soaring interior spaces) and logistically (as a quasi museum with opening hours and a standing staff).67 In contrast to Gregory Sholette’s notion of “mockstitutions,” Gates is establishing new institutions with longevity, and he is doing so parasitically: the Arts Bank was not established along the same official channels as, say, the Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture. Gates is thus generating a new and different order of cultural institutions centered on the long-neglected South Side of Chicago.

In his works, Gates equivocates on an old debate around African American advancement, based on economic versus cultural capital—or business acumen and wealth accumulation versus the fine and liberal arts.68 In foregrounding his own role as artist, Gates provides media friendly cover for his broader project of imagining new black-focused cultural institutions, historical preservation, and investment in housing and businesses. While he operates small-scale job training programs for lower-income African Americans as a form of artistic philanthropy, Gates has simultaneously promoted cultural creation—and consumption—by a largely ignored black middle class.69 In fact, Gates’ urbanist practice might be understood as a way of imagining an alternate history of the late-twentieth-century United States, in which disinvestment in inner cities never occurred, and black cultural institutions flourished. Gates has spoken of developing Black Cinema House, for example, out of his own desire to be able to go see independent films without traveling to art house cinemas on Chicago’s whiter, wealthier North Side. Gates’ ability to generate funding for new cultural institutions is, however, dependent upon his maintenance of a complicated fiction, centered on the identity of social practice artist rather than rapacious developer or community activist.

In his real estate deals, Gates is certainly materially changing low-income black neighborhoods that need improved infrastructure, commerce, services, and validation of lifeways. But his methods for doing so draw upon an idealized image of an artist as simultaneously cultural entrepreneur and spiritual savior, a Joseph Beuys updated for the age of venture capital, privatization of public services, and corporate welfare. While Gates takes the financial mechanisms that underlie both artistic patronage and urban development as the primary thematic of his works, he expands institutional critique’s prior focus on collectors and galleries to include private and public funding support for the arts. Moreover, he does so not solely as a critical move, but as a way to propel his work.70 A key aspect of parasitic practices, then, is a welcoming of institutional support, as opposed to the ambivalent stance of prior generations of institutional critique.

Moreover, parasitic practices differ from institutional critique in that parasitism’s critique is sublimated, and from relational aesthetics’ mobilization of the gift economy because parasitism is embedded in contemporary capitalism. There is a sort of magic to Gates’ work, an alchemy in which his own social capital as artist is transformed into the real financial capital that funds building rehabs and large-scale urban development. That is, institutional critique mounted a frontal attack on the built structures and discursive realms of the art world, while relational aesthetics sought to carve out heterotopic enclaves resistant to instrumentalization or commerce. In contrast, Gates is deeply enmeshed in city government and public-private partnerships that characterize the neoliberal city. If parasitism offers critique, it does so by strategically diverting investment to areas otherwise underserved by government funding and private investment. It is critique in which the artist’s own relative lack of power is mobilized; his visible public identity as a black artist claiming to represent a marginalized community forces the hand of institutions (a city, a wealthy university) seeking more harmonious relations with those communities. Gates is a congenial working partner for public relations coups. The artist’s visible success in an international art context provides a rationale for funding further urbanist projects, while Gates’ urbanism simultaneously acts as an artistic brand that validates the “wokeness” of museums and galleries exhibiting and selling his art objects, a self-reinforcing cycle. Gates’ projects take advantage of slippages in circuits of capital, offering critique as a hand-in-glove relation that seeks efficacy over ethical certainty.

6. Social Practice, A Way Forward?

Critical and curatorial approaches to social practice seem to evade the genre’s more nefarious implications by foregrounding its progressive character, as in the case of Theaster Gates’ utopian interventions on the South Side of Chicago.71 Curators tend to exhibit social practices that resonate with the priorities of recent social-justice movements, which call for greater visibility and political agency for marginalized groups, as well as more robust redistribution of resources in the face of neoliberal weakening of social safety nets. There is also a seemingly radical capaciousness to curators’ definitions of social practice, in that the genre supposedly exceeds the bounds of art qua art. Social practice has, for example, been understood as a continuation of performance art outside the traditional framing devices of the gallery or stage, and curators and critics have also adopted the framework of a Badiouian event.72 Nato Thompson’s Living as Form book, for example, included as social practice such ruptures as “Tahrir Square” and “Wikileaks,” in addition to the reification of social groups or “specific social constituencies” such as the “Mardi Gras Indian Community” of New Orleans.73 Where social practice represents a new mode of art making, it is as a practice centered on challenging the coherence of the social body—who can or should constitute art’s subjects, its audiences, and its makers—rather than a consensus about the ontology of the artwork itself. Parasitic procedures, as a subset of social practice, moreover demand attention to the how, going beyond institutional critique as well to develop new mechanisms for funding and instantiating large-scale and ongoing social investments as art.

But if social practice and parasitism can be understood as art, it is not because they subvert a neoliberal hollowing out of institutionalized civic engagement, but because social practice, including its parasitic versions, offers an expanded understanding of what constitutes art. Social practice should not, then, be understood as a rosy reformulation of human rights, nor in terms of productive criticality, but as critical complicity. Parasitic practices formulate new social configurations centered on proposing ways to distribute, or redistribute, resources in a newly global order. One way that social practice could push forward out of its current impasse, then, is by drawing on the underlying thematic bridging the issues foregrounded by activist groups like Black Lives Matter and the crisis of refugees pouring into Europe: the issue of unrestricted movement in space.74 And it is this nexus that makes the parasitic practices of Theaster Gates, as well as those of artists like Ai Weiwei and Tania Bruguera, slightly out of sync with most social practice. These artists’ endeavors foreground the quotidian lives of Chinese and Cuban citizens, immigrants sans papiers, and African American urbanites, constituencies whose participation in liberalism’s normative rights of citizenship is fraught—restricted by an authoritarian nationstate, displacement and nativist antipathy, or exclusion from economic and legal institutions through structural racism.75 But more than a limited-time social practice, efforts like Gates’ struggle to concretely alter financial circumstances or political agency, to divert the flows of economic and social capital to areas and constituencies that lack such resources. Rather than representing social formations, Gates uses his role as artist to create new networks and institutions, which may then form the grounds of an alternative to the status quo. Yet at the same time, Gates’ practice is wholly in concert with certain philanthropic alternatives to government, with the potential to be just as anti-democratic in its lack of accountability.76 A pessimistic view might understand Gates’ work as simply binding together resource-rich and capital-poor in new formal configurations. But the potential of his work lies in the possibilities of creating new performativities, new social roles with newly imagined access to capital, an artist/shaman/urbanist/entrepreneur as simultaneously utopian and dystopian. What sets apart Gates’ work from a broader field of social practice is just this shift from art as grassroots organization to art as sculpting capital flows.

Notes

Systems just aren’t made of bricks they’re mostly made of people. —Crass (1980)

In 2012, Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates participated in dOCUMENTA with 12 Ballads For Huguenot House, in which construction materials salvaged from an abandoned Chicago home were used to alter the space of a building in Kassel, Germany. The Kassel building had housed displaced French Protestants in the seventeenth century, while the Chicago building that supplied the materials, 6901 South Dorchester Avenue, formed a portion of Gates’ Dorchester Projects, a multi-building zone of arts and community activity located in Chicago’s largely low-income African American community of Woodlawn/Grand Crossing.1 Visually, the rough edges and visible seams of 12 Ballads combined the artistic precedent of Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural interventions, DIY riffs on mid-century modern design, and David Hammons’ allusive assemblage aesthetic. During the dOCUMENTA exhibition, the space hosted a series of events that included performances by Gates’ own zen gospel musical group, the Black Monks of Mississippi, as well as activities such as yoga classes and literary readings, tropes of ephemeral sociability familiar to anyone versed in recent relational and social art practices.2 In discussing the 12 Ballads work, many commentators focused on the aesthetic reworking of materials salvaged from a crumbling Chicago building, or on the parallel histories of forced migration that offered a point of overlap between French Huguenots and Chicago’s African American community.3 Thus Gates was understood, as he himself has described it, to work in the medium of “sculpture and mythmaking.”4

In the field, beyond the spaces of exhibition, Gates rehabs buildings in low-income African American urban areas of the Midwest and turns them into centers for arts and cultural programming. Gates’ activities generate artifacts for exhibition, but their primary focus is urban regeneration. Gates thus operates at the vanguard of recent socially engaged artistic situations, processes, and events that are intended to effect a change in the material circumstances of some of the participants or viewers: the social capital of artists is transferred to politically and economically marginalized populations. These contemporary practices ostensibly sidestep the art market, instead marshaling the resources of large, financially solvent institutions and foundations bound up in networks of global capital in order to materially benefit selected individuals or groups, in Gates’ case, African Americans living in low-income, urban communities in Chicago and other Rust Belt cities. While Gates and other artists rely partially upon art institutions, what marks these practices is that they draw upon a broader range of sources—e.g., elite universities’ investment in local communities, charitable foundations’ efforts to ameliorate social problems, community development corporations’ focus on alleviating urban poverty, federal tax credits intended to spur economic growth in low income neighborhoods—to effect a redistribution of wealth or access to power.

Art institutions certainly remain a necessary component of these “social practice” works, but only insomuch as they recast alleviation of social and economic inequality as cultural production.5 Though such practices have parallels to performance art, institutional critique, and relational aesthetics, these works are thus characterized by a parasitic relation to cultural, civic, and financial institutions. Commentators such as Gregory Sholette have seen a sort of parodic emulation in this mode of contemporary art practice, in which artist collectives offer “miniature replica[s] of institutional cohesion and legitimacy,” or “mockstitutions” which “seemingly fixed institutional participant[s]—the state, city, corporation, prison, museum, school, even the European Union”—feel compelled to support.6 However, Theaster Gates’ project is quite different, resembling instead what Michel Serres has described as the parasite: a figure who interrupts an existing circuit, producing disorder but also generating a different order.7 It is not simply that Gates creates fictitious institutions, or parodies extant institutions. Instead he institutionalizes informal arrangements. Gates himself has explained that, as he moved between “super formal” institutions, such as “museums, the gallery scene, [Chicago Department of] Cultural Affairs” and “super informal” institutions, such as “storefronts, or Walgreens, or Harold’s Chicken,”

I wanted to . . . call attention to . . . the life that is lived between them. And often, the really formal ones are outside of my neighborhood, and the informal ones are often in my neighborhood. So I also wanted to . . . have those two things collide in the way they collide in my life. . . . One of the byproducts of [my] projects is that there would be this kind of spatial collision, or this social collision, that really conflates how my life looks every day.8

Gates makes the ephemeral sociability of the black metropolis visible and concrete, institutionalizing it in the authority of archives and the durability of a newly aestheticized built environment, spaces that may themselves spur new diagonal exchanges across unseen social divides.9 More recently, Gates described his practice as “inventing daily publics and creating the conditions where a public might hang, and then it becomes real interesting when it’s territorial space like on the cusp of gentrification or on the cusp of the white University or on the cusp of an all-black neighborhood.”10 Thus, rather than locating the art of Gates’ practice in objects or performances, his work can more accurately be understood in terms of the new social arrays he generates, social arrays in which the cultural capital of the artist is transformed into concrete monetary investment. Even as Gates’ works materially benefit the neighborhoods in which they are located, Gates’ social position as artist makes his work intelligible as a cultural good available to be consumed by a broad public of art viewers.

In contemporary art, parasitic tactics work in several registers. The artist is often dependent upon, or parasitic upon, the financial and logistical support of various institutions in order to carry out large-scale socially engaged projects. He or she interrupts the flow of money aimed at the production or exhibition of art, diverting money and visibility toward people and communities typically absent from the art world.11 At the same time, art institutions themselves depend upon the artist to validate what might otherwise be half-baked forays into community politics or social services, or real estate ventures thinly disguised as such; this differentiates artistic parasitism from the “irreversible” and unidirectional flow described by Michel Serres. In the case of Gates, his entire practice hinges upon diverting wealth and access to power from extant channels to individuals and groups – typically poor, typically racially marked – otherwise cut off from such agency.12 But even as these “subjects” might be viewed as parasitic upon institutions, art institutions are in turn parasitic upon these subjects’ marginal social positions. To maintain their positions at the forefront of contemporary art—specifically the “social practice” strain—institutions depend upon a steady supply of people (again, typically poor and/or racially marked) with whom (or through whom) social practice can occur. As cultural institutions whose mandates typically involve some sort of community outreach, art institutions receive help validating their missions from social practice’s visible support for marginalized communities.

But this assertion raises the question: if this type of art is validated, or even constituted, by the extra-artistic, where does “the social” lie? Are these activities exemplary of an avant-garde aspiration to unite art and life, predicated upon a fundamental separation between the two realms? Is the social a ground against which art figures?13 Certainly, the very possibility of “socially engaged art” seems predicated on bridging a divide between distinct spheres of art and the social.14 There already exist substantial critiques of this model, both in terms of artistic autonomy and for social scientists who contend that, “Problems arise . . . when ‘social’ begins to mean a type of material, as if the adjective was roughly comparable to other terms like ‘wooden,’ ‘steely,’ ‘biological,’ ‘economical,’ ‘mental,’ ‘organizational,’ or ‘linguistic.’”15 But in addition to the general problem of isolating “the social” as “a kind of material or domain,” to which art can be opposed, there is an even starker divide at play with so-called social practice. For social practice, “the social” signifies “real people,” whom we might identify as the poor, the dispossessed, and/or the sexually or racially marked.16 Just as earlier avant-gardes sought to “expand what is considered artistic and to annex mundane, nonartistic matter,” recent socially-engaged practices take as their protagonists groups of people otherwise absent from the typical workings of the art world, thus absorbing nonartistic humans as artistic matter.17

Gates’ art is not, then, locatable in obvious artistic objects, or in his performances, but in networks of people, political agency, flows of investment; rather than sensual embodiments of marginalized lifeways, the objects that Gates creates or gathers are props, assisting him in staging the ephemeral sociability of the contemporary city. The following pages explore such networks in detail, showing how Gates has drawn upon the financial and political might of institutions such as large research universities, charitable foundations, and governments to act as real estate developer in low-income African American communities of the urban United States. But Gates should not be understood as an artist who performs the role of urbanist. Rather, his ability to generate funding and political will to accomplish projects depends upon his success at inhabiting the role of black contemporary artist. The intelligibility of Gates’ practice as art depends upon his carefully constructed self-presentation as a black contemporary artist, with his social practice works rendered artistic precisely by virtue of their creator’s social position.18 That is, as Michel Serres elaborates, the parasite “builds a new logic,” transmuting superstructure (art, social interactions) into infrastructure (money, property).19

From Gates’ earliest artworks, one can see the performance of blackness as a key problematic, beginning with “Japanese soul food” meals at the incipient Dorchester Projects around 2007. Gates was trained as a ceramicist, and many of his early projects addressed the shared significance of pottery in Japanese and African American cultures.20 In the mid-2000s, Gates invented the character of a Japanese potter, Shoji Yamaguchi, who settled in a Mississippi clay region in the 1960s and married an African American civil-rights activist. Supposedly, after the Yamaguchis’ death in the early 1990s, their son established an institute to continue their work melding Japanese and Southern African American aesthetics and cuisine. Building on this story, Gates threw ceramic plates for carefully-staged “Japanese soul food” meals, where diverse gatherings of people were invited to discuss “issues of race, political difference and inequalities of all sorts.”21

Similar practices include Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 1992 Untitled (Free), in which Tiravanija set up a kitchen at 303 Gallery in New York and served gallery goers free rice and Thai curry, and Liam Gillick’s documenta x installation Discussion Island (1997), which mythologized his Irish heritage by foregrounding a fabled Celtic mode of conflict resolution (carried out on the neutral ground of an island collaboratively maintained by various clans).22 Gates’ works not only mimic Tiravanija’s sensuous instantiation of the gift economy and Gillick’s use of quasi-architectural forms to shape behavior, but they draw upon a story rooted in ethnic identity, though in the case of Gates this was initially displaced onto the fictional character of the half-Black and half-Asian John Yamaguchi.23 Soon, Gates found his own position as an African American artist living in a poor neighborhood area on Chicago’s South Side would prove an even more potent narrative. By 2009, Gates was overtly addressing his own performance of blackness in works such as the lecture/performance, “To Be Pocket: Militaristic Effeminacy, The ‘Hood’ and Adorno’s Last Sermon, or, It’s Over When The Black Marching Band Goes Home.24 Moreover, Gates’ emphasis on semi-industrial, semi-artisanal production is linked, in his own accounts, to identity and biography. In addition to the importance of pottery in African American history, Gates has described his entry into art through work with his father in the construction industry, particularly tarring roofs.25 In performing the black contemporary artist, Gates thus draws upon a particular history of African American culture in relation to desires for authenticity in today’s art world.26 Yet despite similarly mobilizing identity to position his work within the contemporary art world, Gates’ practice contrasts to the “relational aesthetics” of Tiravanija and Gillick.

Where relational aesthetics may constitute ephemeral sociability as a temporary heterotopia within an art context, e.g., a museum, gallery, or international exhibition, Gates parasitically diverts resources from the contemporary art world to create new gathering spaces, new institutional configurations, that seek to alleviate a community’s lack. Gates’ work is thus more intelligible as “social practice art” or “service media art.”27 Early examples of this type of work came to wider attention with Mary Jane Jacobs’ 1993 Sculpture Chicago biennial, entitled “Culture in Action: New Public Art in Chicago.”28 For example, Chicago artist Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s participation in the biennial consisted of a collaboration among artists, a local community television network, and a teacher and students at a high school located in a predominantly Puerto Rican, low-income area of Chicago.29 The teenagers produced videos based in their own lives, which came together to form the multi-screen work Tele-Vecindario [Tele-Neighborhood] (1993), presented in vacant lots at a neighborhood block party during the biennial.30 The pertinent aspect of this project is, however, not so much its final presentation as the process by which it was produced, its blurring of lines between art practice and community organization. Another notable work in the 1993 Sculpture Chicago biennial was the work Flood, a storefront demonstration hydroponic garden organized by artist collective Haha and volunteers located in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago. In addition to producing and distributing garden vegetables and herbs to AIDS hospices and HIV-positive residents of Chicago, the group held bi-weekly meals and educational activities at the storefront.31 As with Mangano-Ovalle’s Tele-Neighborhood, what is notable about Haha’s practice is the difficulty of teasing out its artistic qualities as something distinct from its social or service character. Their presentations did deploy art-historical references. The television monitors of Manglano-Ovalle’s Tele-vecindario, for example, were placed on ersatz plinths formed of plastic milk crates, while the Haha storefront drew upon the precedent of Claes Oldenburg’s Store (1961) and updated it with a 1980s Soho gallery aesthetic with white shelves of catalogs and ephemera surrounding the central demonstration garden. However, ultimately, the artistic intelligibility of Tele-vecindario and Flood lay in the way that Manglano-Ovalle and Haha diverted the resources of the Sculpture Chicago Biennial and displaced the Biennial’s viewers to lower-income, largely non-white neighborhoods (Humboldt Park and Rogers Park)—and social collisions—they might otherwise not have encountered.

In a similar way, Theaster Gates’ practice can be understood to produce social collisions. His artworks assemble networks of people, including the visibly marginalized individuals who are both the subjects (the thematic focus) and objects (beneficiaries) of Gates’ projects, as well as the normative “art viewer” (wealthier, whiter) typically absent around Gates’ spaces on the South Side of Chicago. But his artworks are not simply assemblages of people. Instead, Gates constructs byzantine financial webs to support his spaces of ephemeral sociability (the street, the storefront, the community art center). These spaces act as artworks, while the sense of social purpose masks the extent of Gates’ engagement with contemporary capitalism. Parasitic practices thus act as a subset of social practice. They rely upon the mobile and deterritorialized processes of global capital, while offering justification through the corresponding “artificial, residual, archaic” reterritorializations, a form of self-essentializing as artistic branding which in turn generates financial and logistical support.32 A flow of money, from municipal tax credits to real estate investors, or wealthy philanthropists’ donations to the arts, or from tuition dollars and donations to the University of Chicago, is parasitically interrupted by Gates’ art practice, which finds relevance in today’s art world for its ability to mobilize tropes of minority culture intelligible within contemporary art discourse.

2. Sculptor + Mythmaker

Over the past decade, as Gates has transitioned from emerging to established artist, the nature of his practice has undergone a dramatic shift: from ceramics to architectonic structures, from small-scale events to large institutions. In one view, this move from studio to post-studio practice accompanies the increased availability of financial and logistical resources as Gates’ renown grew. The past decade of Gates’ practice can thus be seen to be oriented around a consistent set of aesthetic concerns, rooted in a rethinking of contemporary African American culture and a fresh take on the potential of art as an engine of urban development. However, this interpretation does not take into account the overall structure of Gates’ work, in that his practice consists of increasingly impressive networks of funding and logistical support, with artistic objects and cultural spaces acting as catalysts.

The Huguenot House of dOCUMENTA 13 existed, that is, as an aesthetic product within the larger ecosystem of Gates’ artistic practice: an extensive strategy to rehab buildings in low-income African American urban areas of the Midwest (Chicago, Omaha, St. Louis), and establish centers for arts and cultural programming. Most famously, for over a decade Gates has lived amidst the Dorchester Projects in the Grand Crossing neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, and it is from one of its component buildings that materials were removed for the Huguenot House work at dOCUMENTA.33 Gates was also instrumental in creating the Washington Park Arts Incubator, an arts and community center inaugurated in 2013 by the University of Chicago, where Gates is employed. In 2014, Gates’ practice expanded to encompass projects that directly address community needs, namely the large-scale residential project, Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative, in which a Chicago Housing Authority complex was transformed into mixed-income housing with an arts focus. Most recently, in 2015, Gates opened the Stony Island Arts Bank, in which an abandoned bank building was rehabbed to create a site for arts programming, as well as an archive centered on the history of black culture in the United States. Its collections include books from the shuttered Prairie Avenue Architecture Bookstore, records from the shuttered Dr. Wax music store, and the archives of famed African American magazines Ebony and Jet, as well as more somber items, such as the Cleveland gazebo where twelve-year-old Tamir Rice was killed by police gunshots in 2014.

Art objects do form an aspect of Gates’ larger practice, in that their sales have played a major role in generating funding for these urbanist or social practice projects. To help fund the Stony Island Arts Bank, Gates famously issued a limited edition of $5,000 “Bank Bonds” made – with a nod to Duchamp – from marble slabs that had formed partitions between urinals in the former bank’s restrooms. In a poetic flow of parasitism, wealth was made material in a 1920s bank building, while the 2000s saw these hunks of precious stone transmogrified back again into currency, which in turn supported the creative restoration of the building.34 However, these Bank Bonds raised only about $500,000 of the roughly $12 million budget for the Arts Bank; the rest came from investors benefitting from federal and state tax credits. Most of the funding, that is, came from the normal avenues for any low-income urban housing project. It is unlikely that Gates could have drawn together enough investment—whether from art sales or urban development tax credits—to accomplish large-scale urbanist projects like the Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative or the Stony Island Arts Bank without having established his bona fides as an artist. However, with regard to an art historical understanding of Gates’ art practice, his museum and gallery shows are largely beside the point.

The architectural detritus and assemblages that Gates exhibits, as well as the art criticism that has built up around his objects and performances, are simply ways of establishing Gates as artist. While the art historian Huey Copeland has described Gates’ objects as “set adrift from the economies that produced [them] in order that black life might thrive elsewhere,” they can also be understood as material manifestations of Gates’ cultural capital.35 In these aesthetic objects, Gates riffs on modernist painting (fire hoses as Frank Stella or Agnes Martin), post-Minimalist sculpture (chunks of rehabbed buildings evoke everything from Gordon Matta-Clark’s building cuts to Rachael Whiteread’s white casts), and African American cultural history (in the manner of David Hammons), a combination of references that support Gates’ strategic inhabitation of a social role as black contemporary artist. Gates’ object-based practice is, however, secondary to his primary aim: diverting the financial and social capital of large networked institutions to achieve ends that seem to evade conventional criteria of aesthetic judgment.

3. Properties and Profits

Gates’ work in real estate and urban development is propelled by his identification as an artist, which allows him to generate financial and logistical support for investment in the guise of cultural production. Undertaking his work as an artist rather than a developer also gives Gates access to a particular array of funding sources. The bulk of Gates’ projects have been carried out under the auspices of the Rebuild Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit established in 2010.36 Rebuild’s activities center on rehabbing buildings in African American communities of the Midwest for the purpose of housing community arts programming. Donations to the Rebuild Foundation are tax deductible, and it has received support from a laundry list of charitable foundations, such as the Pritzker Family Foundation and ArtPlace America, the latter of which is a collaboration among leading philanthropic foundations (including the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and Bloomberg Philanthropies) as well as several major financial institutions (Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, Citibank, Chase, MetLife, and Morgan Stanley).37 In addition to providing support for “general operating expenses,” these organizations have donated funds to specific projects undertaken by the Rebuild Foundation. Examples include the Hyde Park Art House in St. Louis, MO, which has housed urban design and music camps for middle schoolers, and the Carver Bank building in Omaha, NE, where exhibition and performance spaces, artist studios and a small cafe are managed and programmed by the Bemis Art Center.

The prototype for Gates’ broader production remains his multi-building Dorchester Projects complex in Chicago, which has included the Archive House—containing glass lantern slides from the University of Chicago Department of Art History, architectural books from the defunct Prairie Avenue Architecture Bookshop, and vinyl records saved from the demolished Dr. Wax music store, all collections moved to the Stony Island Arts Bank in 2015–and Black Cinema House, a film screening space dedicated to films of the African diaspora. The process of creating these spaces centered on acts of salvage. The cultural artifacts gathered within the Dorchester Projects, the repurposed construction materials that Gates used, and the structures of the buildings themselves have been salvaged from the wreckage of disinvestment in America’s black metropolises, exacerbated by the recent foreclosure crisis.38 Gates’ combination of art, artisanship, and a locally-rooted social mission has proved irresistible to philanthropists whose donations fund the Rebuild Foundation’s work.

However, as the Rebuild Foundation admits, “Most of this work is actually carried out as a for-profit known as Dorchester Projects LLC. The buildings ARE NOT owned by Rebuild Foundation, but most of the wonderful things that happen in them are developed, organized, and managed by Rebuild Foundation.”39 In fact, in June 2011, the Rebuild Foundation received a $15,000 grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation specifically “To support the business plan and legal structure to separate for-profit from not-for-profit activities.”40 Subsequently, in 2012, Dorchester Projects LLC was renamed Theaster Gates Studios, LLC, while separate LLCs were created for each individual building of the Dorchester Projects, e.g., 6901 South Dorchester, LLC, 6916 South Dorchester, LLC, and 6918 South Dorchester. In late 2015, the Rebuild Foundation rebranded itself with a new website that diminished Gates’ visibility, and several buildings that had formerly comprised Gates’ Dorchester Projects were now reinterpreted as “Program Sites” of the Rebuild Foundation. Meanwhile, in the period between 2011 and the present, Gates established a number of other LLCs corresponding to additional buildings in the area. According to corporate filing documents, as of 2016 Theaster Gates was the Manager of LLCs associated with at least eight properties on the 6900 block of South Dorchester Avenue.41 That is, Gates manages these LLCs, and the LLCs are corporate owners of these properties.42