1.

In 1968, Yvonne Rainer wrote an essay criticizing “much of the western dancing we are familiar with” for the way in which, in any given “phrase,” the “focus of attention” is “the part that is the most still” and that registers “like a photograph.”1 Her problem was not the standard complaint that the movement essential to dance is falsified by a still photograph. It was instead that the western dancing she wanted to break away from had the aesthetic of the still photograph built into it—it was already too photographable. What she wanted instead was a dance that refused that aesthetic, that really would be falsified by being photographed. In 1971, James Welling started taking dance classes at the University of Pittsburgh. When, the following year, he started at Cal Arts, he made the decision to become an artist instead of a dancer, but he continued to be interested in dance and especially in Rainer’s essay, which he “read and reread,”2 even as his decision to become an artist turned more specifically into the decision to become a photographer. And much later, in 2014, realizing that he “wasn’t finished with dance,” he began making still photographs of dance performances (fig. 1).

In one way, obviously, there’s a basic tension between what Rainer wanted to do with dance in 1968 and what Welling wants to do with it now. She wanted a dance that resisted the still photo; he wants to make still photos of dancers. But that opposition begins to break down very quickly if only for the obvious reason that she’s a dancer and he’s a photographer: what Rainer wanted was to make dances; what Welling wants is to make photographs. So if we’re going to think about the relation between her dance and his photographs of dancers, the relevant question isn’t what she thought of photography and what he thinks of dance. It’s why she thought dance needed to resist the photograph and why he thinks his photographs need dancers. And, posing the question this way, we will recognize in both Rainer and Welling an interest in movement that is at the same time an interest in action and an interest in the difficulty of understanding, showing and seeing the relation between the movements of our bodies and our acts.

Which is why Aristotle (and the mid-twentieth-century revival of Aristotelian theory of action) is also part of this essay. The question of the movement of our bodies—of what I do when, for example, “I raise my arm” and what others see when they see me raising my arm—was at the heart of this revival. Elizabeth Anscombe thought that it was only because I could know I was raising my arm without actually seeing myself raise it (I don’t know I am doing it “by observation”3) that raising my arm counted as my act. Why? Because if I could know I was raising it just by observing that it was being raised then the question of what I had done (raised my arm) as opposed to the question of what had taken place (my arm went up) never even got asked. Thus, there was a built-in tension between what was done and what was seen: you could only count as doing it if seeing it wasn’t the way you knew you were doing it. And in thinking about Rainer and Welling—in thinking about the relation between seeing movements and seeing acts—that tension will involve both how Aristotle understood what he called “the activity of seeing”4 (which he thought was “not a movement”) and how we are to understand the relation between seeing action in something that is all movement (dance) and seeing action in something that is no movement (the still photo).

2.

So what did Rainer mean to refuse in refusing the photograph? In (Martha) “Graham-oriented modern dance,” she argued, the work is structured as “a continuity that contains high points or focal climaxes,” and these high points produce precisely the still moment that “becomes the focus of attention, registering like a photograph or suspended moment of climax” (MA 266). The stillness is the climax and even when “these climaxes” “come one on the heels of the other,” the movement between them is nothing but “transitions,” “the mechanics of getting from one point of still ‘registration’ to another” (MA 267). It’s as if the physical movement in the dance is causally necessary for but subordinated to the climactic moment that demands to be seen as motionless—in the “suspended moment of climax,” it’s the suspended moment that is the climax.

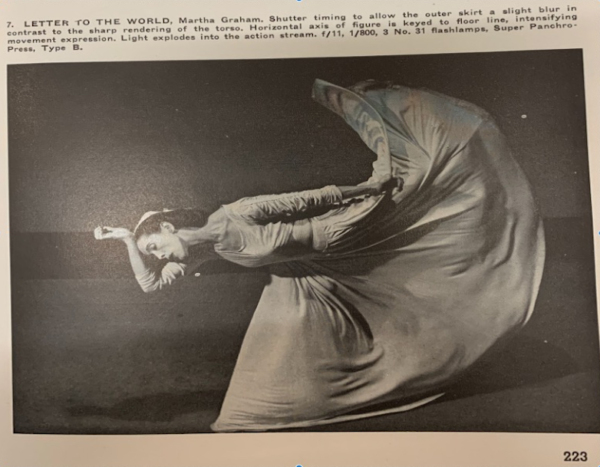

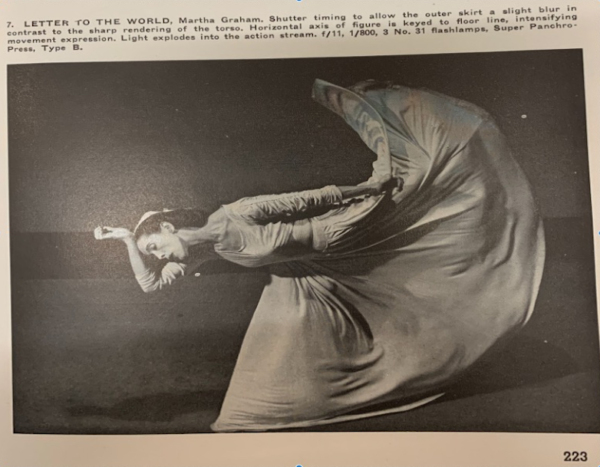

In the photo below, by the great dance photographer Barbara Morgan, we can see a pretty vivid instance of what Rainer was talking about (fig. 2). It’s from Morgan’s essay, “Photographing the Dance,” (which was the first thing Welling ever read about either photography or dance—in 1966, in Graphic Graflex Photography [1947], the manual to the camera his father used) and it brilliantly captures what Morgan called the “ecstatic gesture” which “happens swiftly, and is gone.” But this “elongation of the torso with the fabulous kick” could be translated in Rainer into just the kind of “still, suspended extension” she wanted to get rid of. The very reason that Morgan chose it—its expression of “climactic grief after the loss of the Lover”—would be the reason Rainer, seeking to get rid of “the look of climax,” would reject it. One way, then, to describe Rainer’s ambition was that she wanted a dance where there would be no such gestures (no suspended climaxes) and hence nothing to take a picture of. If, in other words, “Graham-oriented” dance involved transitions, more or less rapid, from one (stilled) photographic point to another, what Rainer wants is for the “limbs” “never” to be “in a fixed still relationship” and to be “stretched to their full extension only in transit, creating the impression that the body is constantly engaged in transitions” (MA 270). Instead of framed stills with transitions between them, no frames and no stills, nothing but transitions.

Why? When she says that the “high points or focal climaxes” out of which Graham-oriented dance was made now seem to be “excessively dramatic and, even more simply, unnecessary,” she offers two reasons, each given a particular point by the fact that “A Quasi Survey” was first published in a book that included texts by Michael Fried and Clement Greenberg. The attack of “Art and Objecthood” on theatricality is just a little over 100 pages from Rainer’s critique of the “excessively dramatic,” and Greenberg, of course, was the one who invented the genealogy that made modernism what was left over once you’d taken from each of the arts everything that was not necessary to them. Which doesn’t, however, mean that Rainer was more Modernist than Minimalist, or what Fried called “literalist.” Rather, it suggests the way that, as Fried himself has pointed out, there’s a direct line from Greenberg’s reduction of painting to “the literal properties of the support” (flatness and the delimitation of flatness) to Minimalism’s valorization of the literal as such and thus to a dance made up, as Carrie Lambert says, of “constant literal motion.”5 And the common ground with respect to Fried himself would be the hostility to the theatrical. But where Fried saw the literal as a kind of theater, Rainer sees it as the escape from theater: her “desired effect was a worklike rather than exhibitionlike presentation” (MA 271). And “The artifice of performance has been reevaluated in that action, or what one does, is more interesting and important than the exhibition of character and attitude” (MA 267).

This is what’s captured by Lambert’s sense that what Rainer offered as an alternative to “a dance of seductive display” was “one of pure materiality”6 and by her association of Rainer’s “Trio A” with Robert Morris’s Minimalism.7 Indeed, Morris’s own essay of 1968, “Anti Form,” produces a reading of Jackson Pollock (and Morris Louis) that anticipates Lambert’s materialist reading of Rainer, focusing on the way Pollock’s “art making” (e.g. the “dripping stick” as opposed to the brush) “acknowledge[d] the nature of the fluidity of paint” and was itself an exercise in materialism; Louis, using “the container itself to pour the fluid,” was even “closer to matter.”8 And, of course, the physical movements of Pollock painting—depicted first in Hans Namuth’s still photos and then in the film he made because stills could not capture the “continuous movement” of what Namuth and everyone else called Pollock’s “dance”9 around the canvas—had already given rise to the idea of what Harold Rosenberg had called action painting: “If the ultimate subject matter of all art is the artist’s psychic state … the innovation of Action Painting was to dispense with the representation of the state in favor of enacting it in physical movement.”10

This is not to say that there wasn’t a significant difference between Rosenberg and both Rainer and Morris. For Rosenberg, as Robert Slifkin has recently emphasized, to see the work of Pollock or De Kooning “solely in terms of the bodily movement … of the artist” (TI 232) would be to miss the artist’s “dramatic relation”11 to what she was doing. By contrast, Rainer’s interest is in the physical movement rather than—indeed, as opposed to—the drama. But it would be a mistake to insist too strongly on this difference. Maybe we could say instead that if Judd’s and Morris’s Minimalism can be described as a radicalization rather than rejection of Greenberg on the literal materials of painting, Rainer’s and Morris’s Minimalism is a radicalization of Rosenberg on the act. Thus, in Rainer’s interest in the “submerging of the personality” in favor of the “neutral ‘doer’” (MA 267), we can see a continuation of what Slifkin convincingly calls Rosenberg’s “sympathy for Aristotle’s conception of action” (TI 219). Precisely because of its concern not with “men” but with their “doings,”12 it’s Aristotelian tragedy that provides the model for the Action Painter’s action.

Furthermore, Rosenberg’s own revision of Aristotle had already suggested the terms of the Minimalist reduction. Tragedy in Aristotle “is the imitation of an act that is complete and whole” and “a whole is that which has a beginning, a middle and an end.”13 But the act in Action Painting, according to Rosenberg, doesn’t: it’s only in the “artifices of the theatre or the historian” that any “act” has a “beginning” or an “end” (AAP 25). Acts outside of artifice “are without beginnings or ends; they’re all middles.” And acts like those of the Action Painter are “powerful middles.”14 For Rosenberg, the difference between a painter like De Kooning and lesser figures was that they were “concerned about how to start a work and how to tell when it was finished” where De Kooning “breaks in anywhere” and then, he says, “I just stop.” The Action Painter doesn’t plan what he’s going to do and doesn’t reach some “resolution” once he’s done it.15 And while Slifkin convincingly traces this sense of action without an end back to Hannah Arendt’s “he who acts never quite knows what he is doing” (TI 239), we can also trace it forward to Morris, for whom the “focus on matter” “results in forms that were not projected in advance” (CP 46).

In fact, Rainer is in some respects even more explicit. She too criticizes dance organized by the “phrase” as a “duration containing beginning, middle and end” (MA 267); that’s the point of all transitions (in effect, all middles). And, as we’ve already seen, she dislikes climaxes at least as much as Rosenberg’s De Kooning dislikes “resolutions.” So perhaps one way to understand the commitment to action is as a commitment to the physical movement of the body and a refusal of the “artifice” that would seek to organize those movements into beginnings, middles, and ends or still moments and climaxes, an account of action that would, as Namuth wanted his film to do (what his photos couldn’t), show the “dance.”

3.

So what does the film show? What did the Action Painter do? And did it have a beginning, middle, and end? If we start with what Slifkin calls the “physical motions” (TI 232)16 of the painter, the answer, Rosenberg, Rainer, and Morris to the contrary notwithstanding, at first seems to be yes. Consider an example of what the philosopher and art critic and theorist, Arthur Danto (taking an example from Wittgenstein) called “one of the standard basic actions”: “raising an arm.”17 Danto calls his arm-raiser “M” and says the action begins when M’s arm starts to move; its middle is while the arm is moving; its end is when it stops. Think of Pollock, waving his arm as he drips one of those arcs of paint onto Cathedral or Autumn Rhythm.

But then think also of the difficulties that attend this description. Pollock’s arm is moving when he mixes the paint, when he dips the stick or brush into the can, and it’s moving when he waves his arm over the canvas, when he dips the stick back into the can and then starts again. Or should we say keeps on going? And, of course, all this time he’s also walking around, moving his legs and other parts of his body. Are those different actions? If our goal is to say what Pollock is doing, which of these physical motions counts? How many acts are there? Perhaps we should say that it’s only when he’s actually using his arm to get the paint on the canvas that it counts as the act in question. But since his arm is moving continuously (the reason Namuth wanted to make a film as well as the stills) you can’t really derive this limit from those movements. Which makes this distinction—it’s one act when he’s getting paint on his brush, another act when he’s getting that paint on the canvas—begin to look arbitrary precisely in the way that Rosenberg suggests when he identifies an act’s beginning and end with “artifice.”

In other words, focusing on the physical motion of the artist does plausibly give rise to a certain interest in the unbounded (all “middle”) understanding of the artist’s act. Indeed, we might go a little further and say that our difficulty in picking out which motion counts as the act suggests (what Rosenberg implies) that part of the interest of Pollock’s paintings is the way that, insofar as we stay focused on the physical motion, they dramatize the arbitrariness of our attempts to specify the beginning, middle, and end of any act. Which suggests in turn that if we do want to talk about a beginning, middle, and end, we need something more than the physical motion. And after all, the point of Wittgenstein’s question—“what’s left over after I raise my arm”—seems to be that there is something left over, that just the physical motion of my arm going up is not enough for me to have raised my arm. Thus, as Danto points out, if M moves his arm because he is “suffering from a nervous disorder”18 or if “someone other than M” moves his arm for him, we won’t want to say that moving his arm was M’s act. A standard way of putting this would just be to say that for M’s moving his arm to count as his act, it would have to be understood as, under some description, intended by M. And then if we wanted to pick out the different acts that were involved in Pollock’s moving his arm, we could say something like—this act is dipping the stick in the can because that’s what he’s intending to do; this one is dripping it onto the canvas because that’s what he’s intending to do, etc. What enables us to attribute beginnings and ends—to distinguish between the different acts—would be the different mental states associated with the continuous physical activity—hence not the physical motion itself but the intention associated with that physical motion.

But this is precisely what Rosenberg and those who have in different ways followed him are skeptical about. If, as Pollock in fact said, “when I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing,” how can we invoke his mental state (i.e., what he is aware of) to identify what he’s doing? Or, since Pollock also says, “there is no beginning and end,”19 how can we appeal to his mental state to identify the moment when he’s stopping doing one thing and starting to do another? And although with respect to Pollock, this unawareness of what he’s doing is identified with a certain view of art—the Action Painter, the man who treats the canvas as the “arena” instead of as the place where “the mind records its contents” (AAP 25)—Pollock not being aware of what he was doing is hardly an anomaly. I’m a medium fast hunt-and-peck typist; are there distinctive mental states that accompany the movement I make with my left forefinger and then with my right forefinger as I type this? Obviously not.

There are two pictures of action here. One says that the act is the physical motion of your body. But that can’t help us pick out which motion is which act—indeed, since you can subdivide every motion into smaller motions, it seems to produce a kind of infinite regress—is it one act for Pollock to move his arm a third of the way over the canvas, another to move it two thirds? To take (from Aristotle) maybe the earliest articulation of this point: if I’m walking from Athens to Delphi, is my first act walking from Athens to Thebes? Is walking from Thebes to Delphi a second act? How can we distinguish them? So the first picture of action has to be supplemented by a second one: it’s not just the physical action but the mental state that accompanies the physical action. But Pollock can be dripping paint onto a canvas without being able to describe his own mental state and, for sure, without being able to distinguish the different mental states—“now I’m moving my arm two inches, now I’m moving it another two inches”—that supposedly accompany the individual movements of his arm. And you can be walking from Athens to Delphi without thinking about whether you’re going to pass Thebes or even about getting to Delphi.

To put the problem this way is to begin to see what has troubled theorists of action but also why the question of what an action is has mattered for artists.20 Before Rosenberg insisted that “an act has no beginning and no end” and a few years even before Pollock said that when he was painting there was “no beginning and no end,”21 Greenberg wrote an essay called “The Crisis of the Easel Picture,” describing the art that was producing the crisis as an art that “dispenses, apparently, with beginning, middle and ending,” an art that—from Manet through Pollock—had gradually repudiated those characteristics of the easel painting that had given it its “unity.”22 “Traditionally,” Greenberg wrote, the “easel painting subordinates decorative to dramatic effect, cutting the illusion of a boxlike cavity into the wall around it, and organizing within this cavity the illusion of forms, light and space … ” (CEP 221). But since Manet, the flattening of this space (what he would a few years later call the refusal of the illusion that it was a space you could enter, a space cut into the wall) threatens the distinction between the painting and the wall in that it threatens the ability of the painting “to hang dramatically on a wall” and therefore runs the risk of turning the picture into nothing but “decoration” (like “wallpaper patterns capable of being extended indefinitely” [CEP 222–23])23 or, in its “uniformity,” of making it into “sheer texture, sheer sensation,” which “as the accumulation of similar series of sensation” would collapse the painting into “a monist naturalism” in which there were no “first and last things” (CEP 224). In other words, what Rosenberg thought of as the great virtue of the work (of Pollock and de Kooning)—no beginning and no end, “all middle”—Greenberg saw as its greatest challenge—no first and no last. For Rosenberg, it was only “artifice” that made us believe that acts had beginnings and ends; for Greenberg, the crisis of the easel picture was precisely the apparent exhaustion of that artifice. And if we see Morris as calling for art to have “a far greater sympathy with matter,” monist naturalism would be a good thing. As it is if we see Rainer as producing a dance of “pure materiality.”

4.

But if we go back to the fascination of Pollock walking around the canvas and especially the gesture of his arm extending over it, we can begin to see not the difficulty of ascribing a beginning and an end to these acts but the impossibility of not doing so. I took the example of walking from Athens to Thebes from the philosopher Douglas Lavin who took it from Aristotle who, pointing out that “the road from Thebes to Athens is the same as the road from Athens to Thebes” also insists that things that are “in this way” “one” are also “not one”: the road uphill is and is not the road downhill.24 The difference obviously is the direction you’re walking—the act of walking from Athens to Thebes is not the same as the act of walking from Thebes to Athens. And this difference is not exactly physical—walking is walking—but not exactly mental either. You’re not walking from Athens to Thebes (or passing through Thebes on your way to Delphi) because you’re thinking about walking from Athens to Thebes through Delphi—you might be thinking about the weather or your desire not to run into your father. The relevant consideration is not your mental state but your purpose.

Lavin puts the point usefully by describing the steps you take as “elements of a teleological structure—each for the sake of the end.”25 Thus in Book X of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle offers “the making of a temple” as a model of action because it is necessarily divided into parts that are “incomplete” (so you can’t identify any “movement” as the act) but which form part of a “complete” act (building) because of their relation to a “goal” (NE 245). So putting together the stone blocks is “incomplete,” as is fluting the columns, and it is “not possible … to find a movement that is complete” but nevertheless “the making of the temple is a complete movement.”

And if we feel the force of this description, we immediately see the problem with the idea of action that underlies both Rosenberg’s hopes and Greenberg’s fears. (And we’ll also see why it’s so central to Pollock’s ambitions and, in fact, Morris’s and Rainer’s ambitions.) When Rosenberg says that “except in the artifices of the theatre or the historian, an act has no beginning and no end,” he’s exactly wrong. In fact, the very idea of an act is possible only as the ordering of one’s physical motions in relation to an end; its essence is the structuring of parts (the steps you’re taking, the extending of your arm) into a whole. So when Greenberg wonders about the work of artists like Pollock dissolving “the picture into sheer texture, sheer sensation, into the accumulation of similar units of sensation,” it’s like dissolving the walk into each separate step, like subdividing the motion of the arm into an infinite number of sequential (i.e., accumulating) but unconnected movements. What he’s basically wondering about is whether the painting is coming to look like the action of making it if that action were disconnected from its purpose—as if the painting were to be regarded as the record or effect of the action rather than its goal.

And, of course, the commitment to the purely material does just that. “The focus on matter … ,” Morris writes, “results in forms that were not projected in advance” (CP 46). And while, unlike Greenberg, he understands himself as welcoming that shift (“chance is accepted and indeterminacy is implied”), he also has a sense of the problem that focusing on the process of “making itself” rather than on what gets made produces even (or especially) for his own interest in making that process visible in the work. For it’s not just that the interest in “making itself” has come at the expense of the interest in the work, it’s that the interest in making itself is no longer really an interest in making. Why? Because what turns the various incomplete and different movements involved in making a temple into the action of making the temple is the “goal” of making a temple; when that goal becomes irrelevant, the movements remain but the action disappears. What you would see on Pollock’s canvas is not what he made but the indexical trace of how he moved. Or, to put it in terms closer to Morris’s own interest in “ends and means” (CP 67), if you don’t care about the ends, the means cease to be means.26

It’s for this reason that, in “Anti Form,” Morris nonetheless praises Pollock precisely for his ability not just to “recover process” but to “hold on to it as part of the end form of the work” (CP 43). And the same logic is even more powerfully at work in Rainer. Her desire to replace “exhibition” by “action, or what one does” doesn’t in itself solve the problem of the “still” moment, registering like a photograph. After all, as we’ve already seen, in any phrase (that is, any segment of “two or more consecutive movements”) there’s still a tendency for some “part of the phrase” (“usually the part that is the most still”) to become the “focus of attention” (MA 266). So the kind of movements she turns to are ones like “getting up from the floor, raising an arm, tilting the pelvis, etc.—much as one would get out of a chair, reach for a high shelf or walk down stairs … ” (MA 270). The attraction of transposing raising an arm into reaching for a high shelf is that there’s no part of reaching for a high shelf that lends itself to becoming the focus of attention, and if you raise your arm not to exhibit the physical movement of your arm but as if you were reaching for a high shelf, there’s no part of the action that registers like a photograph.

Why not? Obviously you can take a picture of someone raising her arm to reach for something. But what Rainer’s logic suggests is that if you’re reaching for something, the photographed part (the still part) misses something crucial about it, what she calls “movement-as-task”—as in, reaching for something from a high shelf. Where Morgan’s picture of Graham captures what Rainer thought mattered to “Graham-oriented” dance—the climactic still moment—no picture of any of the moments involved in reaching for a high shelf can capture what Rainer wants to matter about it—the task. The photograph can capture the expressive but there’s nothing to express in reaching for a high shelf; there’s just what you’re doing.

It’s for this reason, as we’ve seen, that “literal motion” can seem like the alternative. But actually the task makes the literalist alternative—it’s just the physical movement of your arm—as irrelevant as expression. For the idea that the dance consists just in the physical movement of your body makes the task invisible. A photograph of your arm moving isn’t a picture of what you’re doing; reaching for a high shelf counts as an exemplary action for Rainer precisely because it has no still parts, nothing in it that’s purely expressive or purely material. Each movement in the raising of your arm belongs to the action of reaching for the shelf. Even if you paused halfway through, the pause would be an incomplete moment in that action, something that could not be seen in itself but only made visible as an element in the teleological structure. And this is doubly true when there is no shelf to reach for (when the “task” is “task-like”), which by demanding that dance internalize the structure of the task, makes what is “hard to see” “almost impossible to see” (MA 271) but nevertheless seeable.27

Another way to put this is to see the way the degree to which the very idea of a task is central to the Aristotelian understanding of the relations between the physical movements—from putting together the stone blocks to fluting the column—involved in building a temple. In “Anti Form,” Morris wrote that “Form is not perpetuated by means but by preservation of separable idealized ends”; that’s why Greek architecture, “changing from wood to marble,” still looked “the same” (CP 45). But the whole point of the logic of the task is that the means only count as the means if they have at every moment a formal connection to the ends—that is, if all the necessarily “incomplete” motions that go into building the temple are made into the act they are by their structural relation to the end. Hence the action cannot be identified by describing the physical movements you see (any more than it could be describing what the builder is thinking—his mental states). Rather the correct description of the action is in terms of the identification of the task the agent is trying to achieve. That’s why Anscombe, explaining Aristotle’s idea of practical reason and its centrality to the idea of action, says that what he describes is “an order which is there whenever actions are done with intentions.”28 That is, all actions have the structure (not the psychology) of following an order or performing a task: e.g., reach for the high shelf. From this standpoint, it’s as if Rainer’s insistence on the “task-like” in dance is an insistence that the dance be made up not exactly of movements but of actions. Movements are literal; actions she calls “factual” (MA 270). It’s the action that resists the register of the photograph. What resists the still is not so much motion as action.

5.

And it’s not just that the photograph can’t quite make the dancer’s (or even the painter’s) act visible; it’s that the photograph may be understood to have a vexed relation to the photographer’s act. Some version of the question of what the photographer did—basically, in Joseph Pennell’s irritated account, “stick his head in a black box” and “at the crucial moment” let “a machine do everything for him”—has haunted photography on and off almost forever. And it’s striking that this particular defender against Pennell’s charge (W.B. Bolton) complains that, in judging the photograph’s value as art, Pennell places too much emphasis on the means. “To me,” Bolton says, “it seems the means matters not so long as the end is gained, for it is not the materials or the tools that constitute the art … .”29 It’s as if, right from the start, the photograph is lined up both with what Morris would have called a kind of idealism (what matters, its defenders say, is the end not the means) and with a kind of materialism (since, the critics say, it’s not an artist but a machine that does the work—the means make the ends irrelevant).

Furthermore, if we’re thinking about Pollock’s “dance” around the canvas and about Rainer’s Trio A, the physical movements of the photographer might seem utterly beside the point. Maybe the exception would be certain street photographers. Joel Meyerowitz said that the way Robert Frank moved when taking his pictures was “like a ballet,” and Truman Capote described Cartier Bresson as “dancing along the pavement.”30 But James Welling is far from being a street photographer, and even though he actually was a dancer, no one who has ever seen him take a photograph is likely to describe the process as somehow dance-like. More to the point, there’s nothing in the pictures that speaks to his physical movements in making them, the way, say, Garry Winogrand’s tilt does to the position of the camera in his hands.

Which doesn’t mean that the act of making them—what Morris called “the means-end hook-up”—is irrelevant to him. For example, in an interview in connection with the dance pictures I began by mentioning, he observes that “Everyone’s eyes glaze over when they read technical descriptions,” but “that said,” he resolutely goes on to describe the process of making the pictures in Choreograph:

The eye sees color using three receptors, each uniquely sensitive to different wavelengths of light. These three, primary sensations combine in the brain to produce the experience of color. Almost all color processes use variations of these “trichromatic” primaries known as color channels. In Choreograph I’m scrambling the channels in the computer to produce a multilayered, strangely colored photograph.31

In what way is this helpful? Obviously a causal account of how the pictures are made is informative but, compared to the movements of the bodies we’ve been talking about and in fact to the (arrested) movement of the bodies in the pictures themselves, what this photographer does with his body isn’t so interesting—he presses a button, he moves a mouse. In Michael Schreyach’s beautiful book on Pollock, he acknowledges that “viewers commonly experience” his pictures “by reconstructing imaginatively his kinesthetic movements above the canvas surface during his process of painting,” while insisting at the same time that this causal account of how the pictures are made not replace the formal question of what they mean.32 And we’ve seen that distinction taken up by Morris in his suggestion that Pollock managed to make the process part of the end form of the painting. Maybe we could say that insofar as it’s true that people’s eyes glaze over when the technical descriptions start, it’s because the technical descriptions as such are merely causal and don’t have either the drama or the effect of Pollock’s dance—you see the result of the pressed button and the moved mouse, but you don’t see anything like the pressing of the button or the moving of the mouse. In Rainer’s terms, what you see is the still moment that Graham makes visible. But, as we’ve already noted, Rainer’s ambition was to take something that was already “hard to see” and make it “almost impossible to see.” And this seems to me a useful way to describe Welling’s ambition in Choreograph—to make pictures where seeing is a problem, where it needs, in a certain sense, to be overcome.

We can begin to see what this means by looking at the major series of color pictures made some ten years before Choreograph but by very different means. The Glass House pictures are digital photographs made with filters held in front of the lens, a technique that, because it produces the effect of seeing objects in the world through a color (rather than as having a color), immediately produces a certain set of questions recently revived in speculative realism33 but around at least since Locke’s distinction between primary qualities (like “solidity, extension, figure”) and secondary qualities not in the objects themselves but in our experience of them (like taste and color)34 (figs. 3 and 4). Indeed, if you wanted to picture for someone the difference between the primary and the secondary, an economical way to do it would just be to say that everything in these two Glass House photos that’s the same is a primary quality and everything that’s made different by the different filters is secondary.35 One effect of the filters is thus to emphasize—better, to allegorize—the “in us” character of color. That is, we see green and yellow, but in this case, we see the difference between them as signifying not a difference in the world but a difference in the way we see the world. And in Yellow, we see this difference extended to objects that are, in the photo, unfiltered (like the lamp and the desk on the lower right) but that now seem to us to be shown not as they really are but through what is, in effect, the default filter we have already in place.

But the Glass House pictures insist at the same time and by the same mechanism on what’s not “in us.” That is, identifying color with the effect of transparency,36 they produce for us a vision of what we see in the world that is not a function of how we see it, of what is unchanged by the colors through or in which we see it and unchanged therefore by our vision of it. Thus, the very commitment of these photographs to color—to what we see—functions also as an insistence on the independence of that world from our seeing it. Elisabeth Anscombe once remarked (characterizing not only her own experience but what she called “the red patches of Cambridge” moment in analytic philosophy) that there was a time when a sentence like “I see a red patch” as opposed, say, to “I see a red plate” (or a red curtain or red tomato) “seemed to be very clear, very certain, very safe.”37 Why? Because when we see a red plate we may doubt whether there actually is anything (i.e., some material object) “behind” the red patch, but we do not doubt that we are seeing red. The Glass House photos work the opposite way, producing that sense of safety with respect to the objects rather than their color. Indeed, because the color here is so identified with transparency, the question of whether there is anything behind it is answered before it can be asked. Actually, making visible the autonomy of the objects from the colors in which we see them, the pictures refuse the whole idea that what we see is patches of color. And when you juxtapose these two photos in particular, it’s as if their foregrounding of the secondary (color) makes them, in effect, pictures of the primary (what’s not transparent, substance).

Choreograph, made some ten years later, repeats the disconnect of the color from the object and, especially in a picture like the one above (part of which was made at another glass house—Mies’s Farnsworth House), connects it to a thematic of transparency (see fig. 1). But there’s an important difference. Color in Glass House, disconnected from the object, is connected instead to the subject and turned into both a record (when the color is natural) and an allegory (when it isn’t) of our seeing the world. (That’s what it means for color to be distinguished from substance in order to depict substance.) But color in Choreograph can be attached to neither object nor subject. In fact, some of the original photographs here are black and white and the color that’s been generated digitally through Photoshop’s color channels neither records nor refers to what was seen.

One effect of this progression is that the thematic connection between the color and both subject and object is abandoned. For example, in the Glass House photos, it makes sense to think of the house itself as a kind of prism and thus as an objective source for the colors in the pictures while thinking also of the filters held before the camera as a subjective source. Either way, the effect is of a world, and the color insists on its objectivity and our subjectivity (the two require each other) at the same time. In Choreograph, however, the colors are mainly produced by a process that makes it possible for the pictures to refuse both subjectivity (they’re not surrogates for the way we see) and objectivity (they don’t testify to the autonomy of what we see through them). And the further fact that the pictures are made out of more than one photograph doubles down on their unwillingness to give us the sense that they are of a world. For example, the human figures around and through which you see the house are in the picture, but they’re neither inside nor outside the house. And while the color of the landscape outside the house (mainly) belongs to the trees and the leaves (you’re seeing, e.g., green grass), the yellow that dominates the left side of the picture belongs neither to the dancers nor to the subject who sees them, which is to say, it also doesn’t function as an emblem of what does belong to them, e.g., their “solidity.” In fact, the effect of the yellow on the far left is to make the dancer’s arm look like it is somehow both in front of and behind what looks like the built-in cabinets. And that impossibility is only heightened by what happens to the very idea of transparency when it takes the form not of a filter through which you can see people and objects but of the people and objects themselves made into things you see through.

What Choreograph does here is not provide us with the elements of a world—subjects and objects—but refuse to constitute one, and thus, it refuses photography as a way of seeing the world, which is to say, as a way of seeing. We could characterize Welling’s ambition here in terms that reinscribe but also revise what I’ve described as Rainer’s ambition to refuse both what the photograph makes visible (the Martha Graham still) and what seems to be its alternative (literal movement), instead making the action visible. The idea is that Welling’s turn to dance as a subject and to new ways of producing color are themselves an expression of an interest not primarily in technique (i.e., in causal accounts of how the photo was produced) but in action, what the photographer does. But as a photographer, what Welling confronts is the tension we began with—between action and what the photograph makes it possible for us to see (i.e., between dance and photography). The photograph suppresses the action in the service of seeing it and thus suggests the tension between seeing and doing. For if actions have a teleological structure that unites the different movements (e.g., the different stages your arm goes through as you raise it), seeing—which is surely something you do—doesn’t. That’s why, in the course of his discussion of what “kind of thing” pleasure is but at the beginning of a passage that we’ve already noted in our discussion of what kind of thing doing is, Aristotle compares pleasure to the “activity of seeing” and contrasts it with activity that requires “movement” (NE 245). Why is pleasure like seeing? Because both feeling pleasure and seeing are “complete over any given span of time.” That is, they don’t become more complete if they go on for longer, a point you can feel the force of by contrasting seeing, he says, with building. The making of the temple can be divided into movements (putting together the stone blocks, fluting the columns), each of which, taken by itself, is “incomplete.” But seeing the temple is not divisible in the same way. Whether it goes on for a long time or a short time, seeing is always “a kind of whole” in a way that moving isn’t. So seeing is always complete but building is only complete “when it finally does what it aims at.”

Thus, the tension we began with—between dance and photography, between movement and the arrested movement that the photograph makes visible—is registered as a tension between what is necessarily incomplete and what is (equally) necessarily complete. We could say that in Rainer’s account, Martha-Graham-style dancing is an effort to take what is incomplete and in a certain sense unseeable (dancing) and make it complete—make it into a motionless thing, “a kind of whole,” suitable for seeing. And one way to understand Rainer’s own work is as a refusal of this completion, a dance that is nothing but movement. But we’ve also seen why that can’t quite be right, how Rainer’s task refuses both the theater of the still and the literalism of movement. And in Welling, starting not with what moves but what doesn’t, we can see a different effort to undo the “kind of whole” that just is (the whole that the photograph can’t help but be) and to make instead a picture that presents itself both as a still and as a depicted and enacted series of motions, motions which it not only makes visible as parts of a task but as a task that it completes. And which are made into the elements of action all the more vividly by his juxtaposition of dance, which is movement, with architecture, which doesn’t move. The project here is not just to make the photograph into an action (since, of course, it already is) but to make a photograph that, remembering Morris on Pollock, makes the action part of the end form of the work—indeed that insists on the primacy precisely of its form. It’s not the result of an action but something that asks to be understood as the picture of an action.

6.

In her prompt for this issue, Elise Archias asks the contributors to “hold in reserve the reasons” we “have come to appreciate” the work we’re writing about and to ask whether that work doesn’t “also convey something at least supportive of a professional, managerial outlook and self-understanding.” The idea is that, if it does, then there is, or ought to be, a conflict. That is, politically, we ought to be critical of the PMC and so, aesthetically, we ought not to be aligning ourselves with its artists. Of course, a lot hangs on the word “supportive.” It might be argued that simply to be an artist today (to show and sell one’s work) involves belonging to some fraction of the PMC, as, even more obviously, does writing professionally about art. So it would be more or less a given that artists and the people who write about them will belong to a class of which they ought to disapprove. But, in a capitalist society, everybody belongs to a class of which they should disapprove—even, or especially, the working class. The proletariat is privileged by “socialist writers,” Marx says, not because there’s something admirable about it but because, acting in its own interests, it is “compelled” to “abolish itself.”38 And to abolish itself would be to abolish capitalist society, since “the conditions of life of the proletariat sum all the conditions of life of society.”39 So the idea of art made by the working class is problematic (because, in our society, to be an artist is to belong to a class or class fraction that is aligned materially with professionals and managers), and the idea of art made in the interest of the working class is even more problematic (because the true interest of the working class is essentially destructive). Which would mean that the best form of the question of what art is supportive of the PMC or any other class is what art is supportive of capitalism itself.

It’s, in effect, this question that is posed by critics whose commitment is to the revolutionary potential of the avant-garde and who begin to answer it by arguing that many artists, unlike the showing and selling ones I’ve described above, work today in what John Roberts calls a “second economy,”40 liberated (with respect to their art) from the demands of the market by the fact that they don’t make anything that could sell in that market. More literally, they don’t make “things,” and so the difference between things and art that was central to Fried’s critique of minimalism (“Art and Objecthood” attacked it as a kind of literalism precisely because what it made was things) is equally central to Roberts’s critique of Fried’s Modernists—he describes them as “purveyors of luxury dry goods” (RT 680). Thus, there’s a kind of agreement that art isn’t and shouldn’t be a “thing” or at least what Adorno called a “mere thing,” since, as Adorno put it, “if it is essential to artworks that they be things, it is no less essential that they negate their own status as things … the totally objectivated artwork would congeal into a mere thing.”41

Obviously, Roberts’s repudiation of the luxury dry good strikes a polemical note that’s different from Fried, who didn’t like McCracken planks but wasn’t bothered by the fact that people might buy them. But Roberts’s commitment to the autonomy of art (without which “art would simply cease to exist as a tradition of aesthetic and intellectual achievement and … as a means of resistance to the heteronomy of capitalist exchange” [RT 1032]) is just as strong as Fried’s and, in fact, following Nick Brown’s reading of Fried, is a version of Fried’s. From this standpoint, if we take Archias’s question about art that is supportive of the PMC as a question about art that is supportive of capitalism, we can see that it’s only incidentally a question about art’s compatibility with the self-understanding of one class rather than another; it’s fundamentally a question about what there can be in art that isn’t reducible to the self-understanding of any class—a question about what in art isn’t reducible to the thing. And we see also why since Pollock and De Kooning and Louis, the act has mattered—it’s the alternative to the thing.

Not, of course, the only alternative to the thing. But the other alternative—conceptualism—has always been plagued by the fantasies about meaning and intention that it found embodied in what Kosuth called the “first unassisted readymade.”42 Indeed, part of the attraction of action is its almost automatic displacement of the reification of both concept and thing exemplified by the readymade and doubled down on by the “unassisted.” The act is not in your head, and it’s not an object. Except that, as we’ve already seen, the tendency to turn it into one or the other (or both) is strong. If you think that intention needs to be added to the movement of your arm to turn it into an action, you’re already a conceptualist. And, in this essay, we’ve already seen how—literalized, understood as movement, in effect, deteleologized—the act is made into a thing. The brilliance of Rainer’s “Quasi Survey of Some ‘Minimalist’ Tendencies” is that she doesn’t do this. Unlike the avatars of Action Painting and unlike most of the Minimalists (including Morris), she produces the problem of the (moving) thing in the act itself and thus produces the solution of seeing the act in the art.

For someone like Roberts, however, for whom the very idea of the artwork—the “sensuous” and “aestheticist” dry good—is the problem, the solution is not to make the act visible in the work but to replace the work with the act, to insist on the “space between art-as-praxis and the contemplative spectator of painterly modernism” (RT 3679). The avant-garde “research communities” (RT 3436) and “research programmes” (RT 3618) he values don’t make things to be contemplated. In a sense, they don’t make things at all; they make praxis possible. And, if we want to distinguish between art and the luxury dry good (which we do!), this distinction makes sense—the luxury dry good requires nothing of us. But, leaving aside the question of just what Roberts’s avant-garde requires of its audience, his conception of what modernism requires (and, really, the whole idea of the passivity of the beholder or of the reader) is cripplingly impoverished. We all know the story of Joyce supposedly saying that since it took him seventeen years to write Finnegans Wake, he didn’t see why it shouldn’t take someone seventeen years to read it. The point of the joke is precisely the demand made on the reader, which is to say the demand not, obviously, to run her eyes over the writing or even to respond to it but to understand it. Which us to say, the demand for the reader’s work.

Indeed, Roberts’s avant-garde “research communities” with “research programmes” are prefigured in Finnegans Wake and its readers and even more vividly in the painterly modernisms that go further and demand a relation to an entire history of painting in order to be experienced the way they’re supposed to be. The artwork turned into the luxury dry good is the sensuous thing that doesn’t need to be understood, just responded to—it’s like a sunset that you can buy. But perhaps the least controversial thing one could possibly say about work under the sign of Modernism is that it requires to be understood and that often it’s hard to understand. You have to look at it for a long time; you have to look at other things that were made before it but that are connected to it; you have to read stuff that’s been written about them and about it. And you have to do all that not as a kind of refusal of its sensuousness (that would be conceptualism) but as a way of understanding how it understands its sensuousness.

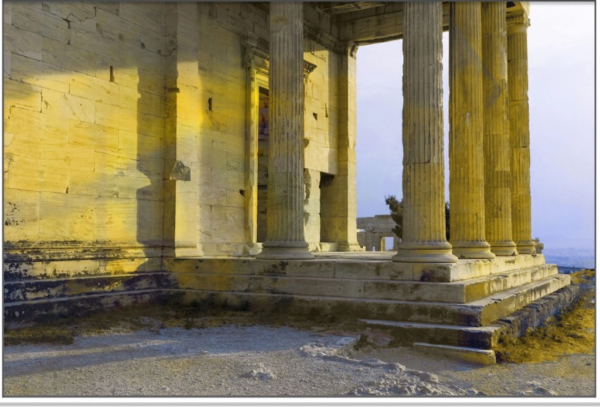

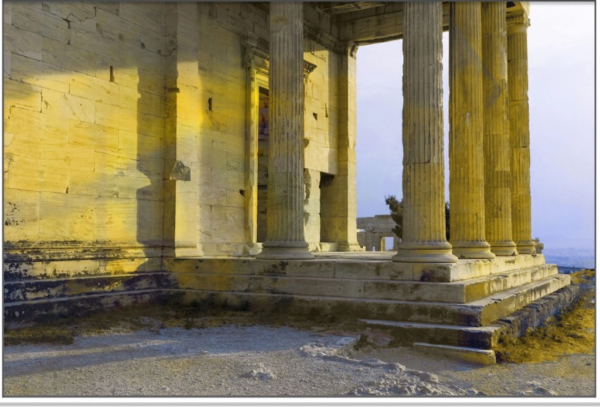

In this sense, the disarticulation of art from the aesthetic misses the point. In fact, insofar as it’s now crucial to assert the claim to art against the luxury dry good, not just the aesthetic but the beautiful becomes essential. Luxury goods, sunsets, are beautiful. But if, from one standpoint, it has looked like the radical alternative to them must be something that isn’t beautiful, the actual relevant alternative is something that, beautiful or not, demands our understanding, and the demand for understanding asserts itself most powerfully when embodied not just in the display of beauty that has often characterized Welling’s work but in the way he doubles down on that display in the architectural photographs made alongside of, just after, and even with the Choreograph pictures (figs. 5 and 6). Because the idea here is not just that they’re beautiful. It’s that in their subjects—here, the Erectheion and the Propylaea on the Acropolis—they are virtually the prototypes for a certain conception of what beauty is. In fact, the column, crucial to both pictures, was, according to Hegel, the “fundamental element” in the “beauty” of Greek architecture.43 It’s as if the subject of these photographs is itself that conception of beauty.

Furthermore, both pictures not only revisit the sources of that conception but recapitulate certain moments in its participation in the history of photography and in Welling’s own longstanding interest in that history. Relevant here would be not just the nineteenth-century archeological photos of the Acropolis or Welling’s own earlier architectural photos (before the Glass House pictures, his Richardsons) but his revolutionary Drapes and Aluminum Foil pictures of the early eighties. Why are these relevant? Because part of what was revolutionary about them was their refusal of the logic of the view basically built into the whole idea of archeological and architectural photography. The Aluminum Foil pictures manage to carry with them the ghost of a version of that logic—they almost look like landscapes—but only to insist that it’s crucial to their meaning that they aren’t views. Just the opposite, the relation between the uneven surface of their actual subject and the absolutely even surface of the photograph itself denies the relevance of the view—of the photographer’s eye as such—with a formal brilliance that matches the thematic brilliance of another celebrated refusal of the view, Gursky’s Klausen Pass (1984).

But Erectheion and Propylaea are views. And Erechtheion is not only a view; it’s a view of a very beautiful thing, and it’s a view of a very beautiful thing at sunset. Here what has been refused as view is reclaimed as concept. For if, in one sense, these photographs epitomize both a certain idea of beauty (the Acropolis at sunset) and of the photographer’s relation to it (his ability to capture it for the viewer), they do so in the process of (really in the service of) recapitulating the history of photography as art. One way to put this would be to say they are views about views. But, digitally altered in one case, hand altered in the other, their real commitment is to redescribing and answering the skeptical question about the photographer—what does he do? The original point of the question was to deny photography’s status as a fine art by insisting that, compared to the painter, the photographer did nothing—he just pressed a button; the camera did the work. The problem, as Steiglitz diagnosed it, was the “fatal facility”44 with which it mistakenly seemed anyone could make a good photograph, and he and many others were concerned to point out the mistake. Steiglitz himself was especially interested in the effects individual photographers could produce through the printing process, and Erechtheion is significantly an artifact of that process. Where the original camera file was, as Welling himself describes it, “a dull humid sunset,”45 the work itself is saturated with Photoshop’s yellows, on the ground as well as the marble, and the light fixtures at the building’s base (to illuminate it by night) have been retouched out. Furthermore, the Propylaea is made out of a photograph printed on to a polyester plate to which a “thick layer of oil paint” was then applied by hand.

It’s as if both lines of response to the critic’s skepticism—the appeal both to the photographer’s eye and to his hand, Sadakichi Hartman’s exhortation to “compose the picture” and eschew “manipulation” of the negative and the Photo-Secessionist “brush marks” he objected to—have been mobilized here.46 But the function they serve is not to satisfy anyone of the photographer’s skill. Rather, just as the sunset here becomes the commitment to the concept, the handmade becomes the commitment to the act. It’s only when the question of skill is rendered secondary that the question of what the artist does becomes truly central.

It’s in this context that we should understand the force of Welling’s affection for boring “technical descriptions.” The account of how he made these pictures is definitely the account of a certain set of skills, but the skills are relevant only in the way Pollock’s “technique” was—it’s skill after deskilling. Just as the middlebrow skepticism about abstract painting repeated the earlier skepticism about the photograph as art (neither requires any skill), the emergence of photography as a kind of successor to abstract painting turned the question of skill into the question of the act and, in work like Welling’s, makes the photograph a test case for the act. It makes the technical description less an account of how one did it than an account of what one does. We can adopt Archias’s philistine hypothesis and hold in reserve the question of whether we like what the artist did. With respect to the green version of the yellow Glass House, we might even agree with Welling himself that it doesn’t succeed. But even to see how it fails is to see it not in terms of a professional or managerial (i.e., our) self-understanding but in terms of how it understands itself. And the difference between our understanding of ourselves and our understanding of the work suggests the possibility of a class analysis that isn’t reducible to the expression of a class interest.

Notes

1.

In 1968, Yvonne Rainer wrote an essay criticizing “much of the western dancing we are familiar with” for the way in which, in any given “phrase,” the “focus of attention” is “the part that is the most still” and that registers “like a photograph.”1 Her problem was not the standard complaint that the movement essential to dance is falsified by a still photograph. It was instead that the western dancing she wanted to break away from had the aesthetic of the still photograph built into it—it was already too photographable. What she wanted instead was a dance that refused that aesthetic, that really would be falsified by being photographed. In 1971, James Welling started taking dance classes at the University of Pittsburgh. When, the following year, he started at Cal Arts, he made the decision to become an artist instead of a dancer, but he continued to be interested in dance and especially in Rainer’s essay, which he “read and reread,”2 even as his decision to become an artist turned more specifically into the decision to become a photographer. And much later, in 2014, realizing that he “wasn’t finished with dance,” he began making still photographs of dance performances (fig. 1).

In one way, obviously, there’s a basic tension between what Rainer wanted to do with dance in 1968 and what Welling wants to do with it now. She wanted a dance that resisted the still photo; he wants to make still photos of dancers. But that opposition begins to break down very quickly if only for the obvious reason that she’s a dancer and he’s a photographer: what Rainer wanted was to make dances; what Welling wants is to make photographs. So if we’re going to think about the relation between her dance and his photographs of dancers, the relevant question isn’t what she thought of photography and what he thinks of dance. It’s why she thought dance needed to resist the photograph and why he thinks his photographs need dancers. And, posing the question this way, we will recognize in both Rainer and Welling an interest in movement that is at the same time an interest in action and an interest in the difficulty of understanding, showing and seeing the relation between the movements of our bodies and our acts.

Which is why Aristotle (and the mid-twentieth-century revival of Aristotelian theory of action) is also part of this essay. The question of the movement of our bodies—of what I do when, for example, “I raise my arm” and what others see when they see me raising my arm—was at the heart of this revival. Elizabeth Anscombe thought that it was only because I could know I was raising my arm without actually seeing myself raise it (I don’t know I am doing it “by observation”3) that raising my arm counted as my act. Why? Because if I could know I was raising it just by observing that it was being raised then the question of what I had done (raised my arm) as opposed to the question of what had taken place (my arm went up) never even got asked. Thus, there was a built-in tension between what was done and what was seen: you could only count as doing it if seeing it wasn’t the way you knew you were doing it. And in thinking about Rainer and Welling—in thinking about the relation between seeing movements and seeing acts—that tension will involve both how Aristotle understood what he called “the activity of seeing”4 (which he thought was “not a movement”) and how we are to understand the relation between seeing action in something that is all movement (dance) and seeing action in something that is no movement (the still photo).

2.

So what did Rainer mean to refuse in refusing the photograph? In (Martha) “Graham-oriented modern dance,” she argued, the work is structured as “a continuity that contains high points or focal climaxes,” and these high points produce precisely the still moment that “becomes the focus of attention, registering like a photograph or suspended moment of climax” (MA 266). The stillness is the climax and even when “these climaxes” “come one on the heels of the other,” the movement between them is nothing but “transitions,” “the mechanics of getting from one point of still ‘registration’ to another” (MA 267). It’s as if the physical movement in the dance is causally necessary for but subordinated to the climactic moment that demands to be seen as motionless—in the “suspended moment of climax,” it’s the suspended moment that is the climax.

In the photo below, by the great dance photographer Barbara Morgan, we can see a pretty vivid instance of what Rainer was talking about (fig. 2). It’s from Morgan’s essay, “Photographing the Dance,” (which was the first thing Welling ever read about either photography or dance—in 1966, in Graphic Graflex Photography [1947], the manual to the camera his father used) and it brilliantly captures what Morgan called the “ecstatic gesture” which “happens swiftly, and is gone.” But this “elongation of the torso with the fabulous kick” could be translated in Rainer into just the kind of “still, suspended extension” she wanted to get rid of. The very reason that Morgan chose it—its expression of “climactic grief after the loss of the Lover”—would be the reason Rainer, seeking to get rid of “the look of climax,” would reject it. One way, then, to describe Rainer’s ambition was that she wanted a dance where there would be no such gestures (no suspended climaxes) and hence nothing to take a picture of. If, in other words, “Graham-oriented” dance involved transitions, more or less rapid, from one (stilled) photographic point to another, what Rainer wants is for the “limbs” “never” to be “in a fixed still relationship” and to be “stretched to their full extension only in transit, creating the impression that the body is constantly engaged in transitions” (MA 270). Instead of framed stills with transitions between them, no frames and no stills, nothing but transitions.

Why? When she says that the “high points or focal climaxes” out of which Graham-oriented dance was made now seem to be “excessively dramatic and, even more simply, unnecessary,” she offers two reasons, each given a particular point by the fact that “A Quasi Survey” was first published in a book that included texts by Michael Fried and Clement Greenberg. The attack of “Art and Objecthood” on theatricality is just a little over 100 pages from Rainer’s critique of the “excessively dramatic,” and Greenberg, of course, was the one who invented the genealogy that made modernism what was left over once you’d taken from each of the arts everything that was not necessary to them. Which doesn’t, however, mean that Rainer was more Modernist than Minimalist, or what Fried called “literalist.” Rather, it suggests the way that, as Fried himself has pointed out, there’s a direct line from Greenberg’s reduction of painting to “the literal properties of the support” (flatness and the delimitation of flatness) to Minimalism’s valorization of the literal as such and thus to a dance made up, as Carrie Lambert says, of “constant literal motion.”5 And the common ground with respect to Fried himself would be the hostility to the theatrical. But where Fried saw the literal as a kind of theater, Rainer sees it as the escape from theater: her “desired effect was a worklike rather than exhibitionlike presentation” (MA 271). And “The artifice of performance has been reevaluated in that action, or what one does, is more interesting and important than the exhibition of character and attitude” (MA 267).

This is what’s captured by Lambert’s sense that what Rainer offered as an alternative to “a dance of seductive display” was “one of pure materiality”6 and by her association of Rainer’s “Trio A” with Robert Morris’s Minimalism.7 Indeed, Morris’s own essay of 1968, “Anti Form,” produces a reading of Jackson Pollock (and Morris Louis) that anticipates Lambert’s materialist reading of Rainer, focusing on the way Pollock’s “art making” (e.g. the “dripping stick” as opposed to the brush) “acknowledge[d] the nature of the fluidity of paint” and was itself an exercise in materialism; Louis, using “the container itself to pour the fluid,” was even “closer to matter.”8 And, of course, the physical movements of Pollock painting—depicted first in Hans Namuth’s still photos and then in the film he made because stills could not capture the “continuous movement” of what Namuth and everyone else called Pollock’s “dance”9 around the canvas—had already given rise to the idea of what Harold Rosenberg had called action painting: “If the ultimate subject matter of all art is the artist’s psychic state … the innovation of Action Painting was to dispense with the representation of the state in favor of enacting it in physical movement.”10

This is not to say that there wasn’t a significant difference between Rosenberg and both Rainer and Morris. For Rosenberg, as Robert Slifkin has recently emphasized, to see the work of Pollock or De Kooning “solely in terms of the bodily movement … of the artist” (TI 232) would be to miss the artist’s “dramatic relation”11 to what she was doing. By contrast, Rainer’s interest is in the physical movement rather than—indeed, as opposed to—the drama. But it would be a mistake to insist too strongly on this difference. Maybe we could say instead that if Judd’s and Morris’s Minimalism can be described as a radicalization rather than rejection of Greenberg on the literal materials of painting, Rainer’s and Morris’s Minimalism is a radicalization of Rosenberg on the act. Thus, in Rainer’s interest in the “submerging of the personality” in favor of the “neutral ‘doer’” (MA 267), we can see a continuation of what Slifkin convincingly calls Rosenberg’s “sympathy for Aristotle’s conception of action” (TI 219). Precisely because of its concern not with “men” but with their “doings,”12 it’s Aristotelian tragedy that provides the model for the Action Painter’s action.

Furthermore, Rosenberg’s own revision of Aristotle had already suggested the terms of the Minimalist reduction. Tragedy in Aristotle “is the imitation of an act that is complete and whole” and “a whole is that which has a beginning, a middle and an end.”13 But the act in Action Painting, according to Rosenberg, doesn’t: it’s only in the “artifices of the theatre or the historian” that any “act” has a “beginning” or an “end” (AAP 25). Acts outside of artifice “are without beginnings or ends; they’re all middles.” And acts like those of the Action Painter are “powerful middles.”14 For Rosenberg, the difference between a painter like De Kooning and lesser figures was that they were “concerned about how to start a work and how to tell when it was finished” where De Kooning “breaks in anywhere” and then, he says, “I just stop.” The Action Painter doesn’t plan what he’s going to do and doesn’t reach some “resolution” once he’s done it.15 And while Slifkin convincingly traces this sense of action without an end back to Hannah Arendt’s “he who acts never quite knows what he is doing” (TI 239), we can also trace it forward to Morris, for whom the “focus on matter” “results in forms that were not projected in advance” (CP 46).

In fact, Rainer is in some respects even more explicit. She too criticizes dance organized by the “phrase” as a “duration containing beginning, middle and end” (MA 267); that’s the point of all transitions (in effect, all middles). And, as we’ve already seen, she dislikes climaxes at least as much as Rosenberg’s De Kooning dislikes “resolutions.” So perhaps one way to understand the commitment to action is as a commitment to the physical movement of the body and a refusal of the “artifice” that would seek to organize those movements into beginnings, middles, and ends or still moments and climaxes, an account of action that would, as Namuth wanted his film to do (what his photos couldn’t), show the “dance.”

3.

So what does the film show? What did the Action Painter do? And did it have a beginning, middle, and end? If we start with what Slifkin calls the “physical motions” (TI 232)16 of the painter, the answer, Rosenberg, Rainer, and Morris to the contrary notwithstanding, at first seems to be yes. Consider an example of what the philosopher and art critic and theorist, Arthur Danto (taking an example from Wittgenstein) called “one of the standard basic actions”: “raising an arm.”17 Danto calls his arm-raiser “M” and says the action begins when M’s arm starts to move; its middle is while the arm is moving; its end is when it stops. Think of Pollock, waving his arm as he drips one of those arcs of paint onto Cathedral or Autumn Rhythm.

But then think also of the difficulties that attend this description. Pollock’s arm is moving when he mixes the paint, when he dips the stick or brush into the can, and it’s moving when he waves his arm over the canvas, when he dips the stick back into the can and then starts again. Or should we say keeps on going? And, of course, all this time he’s also walking around, moving his legs and other parts of his body. Are those different actions? If our goal is to say what Pollock is doing, which of these physical motions counts? How many acts are there? Perhaps we should say that it’s only when he’s actually using his arm to get the paint on the canvas that it counts as the act in question. But since his arm is moving continuously (the reason Namuth wanted to make a film as well as the stills) you can’t really derive this limit from those movements. Which makes this distinction—it’s one act when he’s getting paint on his brush, another act when he’s getting that paint on the canvas—begin to look arbitrary precisely in the way that Rosenberg suggests when he identifies an act’s beginning and end with “artifice.”

In other words, focusing on the physical motion of the artist does plausibly give rise to a certain interest in the unbounded (all “middle”) understanding of the artist’s act. Indeed, we might go a little further and say that our difficulty in picking out which motion counts as the act suggests (what Rosenberg implies) that part of the interest of Pollock’s paintings is the way that, insofar as we stay focused on the physical motion, they dramatize the arbitrariness of our attempts to specify the beginning, middle, and end of any act. Which suggests in turn that if we do want to talk about a beginning, middle, and end, we need something more than the physical motion. And after all, the point of Wittgenstein’s question—“what’s left over after I raise my arm”—seems to be that there is something left over, that just the physical motion of my arm going up is not enough for me to have raised my arm. Thus, as Danto points out, if M moves his arm because he is “suffering from a nervous disorder”18 or if “someone other than M” moves his arm for him, we won’t want to say that moving his arm was M’s act. A standard way of putting this would just be to say that for M’s moving his arm to count as his act, it would have to be understood as, under some description, intended by M. And then if we wanted to pick out the different acts that were involved in Pollock’s moving his arm, we could say something like—this act is dipping the stick in the can because that’s what he’s intending to do; this one is dripping it onto the canvas because that’s what he’s intending to do, etc. What enables us to attribute beginnings and ends—to distinguish between the different acts—would be the different mental states associated with the continuous physical activity—hence not the physical motion itself but the intention associated with that physical motion.

But this is precisely what Rosenberg and those who have in different ways followed him are skeptical about. If, as Pollock in fact said, “when I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing,” how can we invoke his mental state (i.e., what he is aware of) to identify what he’s doing? Or, since Pollock also says, “there is no beginning and end,”19 how can we appeal to his mental state to identify the moment when he’s stopping doing one thing and starting to do another? And although with respect to Pollock, this unawareness of what he’s doing is identified with a certain view of art—the Action Painter, the man who treats the canvas as the “arena” instead of as the place where “the mind records its contents” (AAP 25)—Pollock not being aware of what he was doing is hardly an anomaly. I’m a medium fast hunt-and-peck typist; are there distinctive mental states that accompany the movement I make with my left forefinger and then with my right forefinger as I type this? Obviously not.

There are two pictures of action here. One says that the act is the physical motion of your body. But that can’t help us pick out which motion is which act—indeed, since you can subdivide every motion into smaller motions, it seems to produce a kind of infinite regress—is it one act for Pollock to move his arm a third of the way over the canvas, another to move it two thirds? To take (from Aristotle) maybe the earliest articulation of this point: if I’m walking from Athens to Delphi, is my first act walking from Athens to Thebes? Is walking from Thebes to Delphi a second act? How can we distinguish them? So the first picture of action has to be supplemented by a second one: it’s not just the physical action but the mental state that accompanies the physical action. But Pollock can be dripping paint onto a canvas without being able to describe his own mental state and, for sure, without being able to distinguish the different mental states—“now I’m moving my arm two inches, now I’m moving it another two inches”—that supposedly accompany the individual movements of his arm. And you can be walking from Athens to Delphi without thinking about whether you’re going to pass Thebes or even about getting to Delphi.

To put the problem this way is to begin to see what has troubled theorists of action but also why the question of what an action is has mattered for artists.20 Before Rosenberg insisted that “an act has no beginning and no end” and a few years even before Pollock said that when he was painting there was “no beginning and no end,”21 Greenberg wrote an essay called “The Crisis of the Easel Picture,” describing the art that was producing the crisis as an art that “dispenses, apparently, with beginning, middle and ending,” an art that—from Manet through Pollock—had gradually repudiated those characteristics of the easel painting that had given it its “unity.”22 “Traditionally,” Greenberg wrote, the “easel painting subordinates decorative to dramatic effect, cutting the illusion of a boxlike cavity into the wall around it, and organizing within this cavity the illusion of forms, light and space … ” (CEP 221). But since Manet, the flattening of this space (what he would a few years later call the refusal of the illusion that it was a space you could enter, a space cut into the wall) threatens the distinction between the painting and the wall in that it threatens the ability of the painting “to hang dramatically on a wall” and therefore runs the risk of turning the picture into nothing but “decoration” (like “wallpaper patterns capable of being extended indefinitely” [CEP 222–23])23 or, in its “uniformity,” of making it into “sheer texture, sheer sensation,” which “as the accumulation of similar series of sensation” would collapse the painting into “a monist naturalism” in which there were no “first and last things” (CEP 224). In other words, what Rosenberg thought of as the great virtue of the work (of Pollock and de Kooning)—no beginning and no end, “all middle”—Greenberg saw as its greatest challenge—no first and no last. For Rosenberg, it was only “artifice” that made us believe that acts had beginnings and ends; for Greenberg, the crisis of the easel picture was precisely the apparent exhaustion of that artifice. And if we see Morris as calling for art to have “a far greater sympathy with matter,” monist naturalism would be a good thing. As it is if we see Rainer as producing a dance of “pure materiality.”

4.

But if we go back to the fascination of Pollock walking around the canvas and especially the gesture of his arm extending over it, we can begin to see not the difficulty of ascribing a beginning and an end to these acts but the impossibility of not doing so. I took the example of walking from Athens to Thebes from the philosopher Douglas Lavin who took it from Aristotle who, pointing out that “the road from Thebes to Athens is the same as the road from Athens to Thebes” also insists that things that are “in this way” “one” are also “not one”: the road uphill is and is not the road downhill.24 The difference obviously is the direction you’re walking—the act of walking from Athens to Thebes is not the same as the act of walking from Thebes to Athens. And this difference is not exactly physical—walking is walking—but not exactly mental either. You’re not walking from Athens to Thebes (or passing through Thebes on your way to Delphi) because you’re thinking about walking from Athens to Thebes through Delphi—you might be thinking about the weather or your desire not to run into your father. The relevant consideration is not your mental state but your purpose.

Lavin puts the point usefully by describing the steps you take as “elements of a teleological structure—each for the sake of the end.”25 Thus in Book X of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle offers “the making of a temple” as a model of action because it is necessarily divided into parts that are “incomplete” (so you can’t identify any “movement” as the act) but which form part of a “complete” act (building) because of their relation to a “goal” (NE 245). So putting together the stone blocks is “incomplete,” as is fluting the columns, and it is “not possible … to find a movement that is complete” but nevertheless “the making of the temple is a complete movement.”