We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn’t do it, but God could.

—Congressman Richard Baker, Baton Rouge

They can put me in jail …. I’m seventy years old, and I wanna come home. If I got to die, let me die in New Orleans!

—Gloria “Mama Glo” Irving, St. Bernard public housing resident

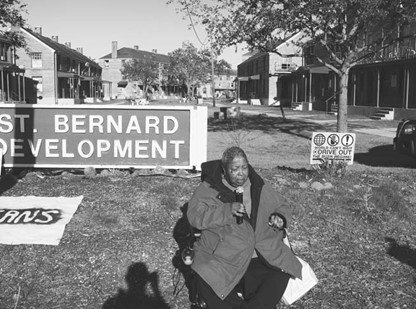

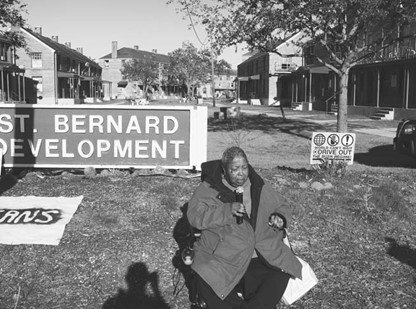

“What do we want? … Our Homes!” This was the heartfelt call-and-response chant invoked by a contingent of St. Bernard public housing residents and supporters marching toward a driveway that led into their now-shuttered community. On April 4, 2006, the thirty-eighth anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and seven months after being forced out by Hurricane Katrina’s floodwaters bursting of the city’s decaying levees, displaced public housing residents were making it clear that they were coming home. The marchers—led by seventy-year-old, wheel chair–propelled Gloria “Mama Glo” Irving—were greeted by a phalanx of HANO and New Orleans police and a recently erected chain link fence. The protestors were undeterred. In her wheelchair, Mama Glo—pushed by former St. Bernard resident and HANO chairman Endesha Juakali and ignoring orders from HANO police chief Mitchell Dussett to stop—burst through the police line and led the marchers into the development.1

Why did St. Bernard and other public housing residents have to fight the police and face arrest simply to return home? How could national and local authorities selectively block public housing residents—and not other displaced New Orleanians—from exercising their right of return in the wake of a human-made disaster? Indeed, the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and other treaties to which the United States is a signatory codify the right of return, making it the responsibility of governments to facilitate—not block—the return of displaced people.2 Public housing authorities did raise concerns of contaminated soil to justify the continued closure of developments, but this danger was no greater than that faced by other displaced New Orleanians who were allowed to return. Likewise, the damage sustained by public housing structures could not explain why residents were barred from their homes. In fact, several located in the center of the city—Iberville, Lafitte, and C. J. Peete—faced little or no flooding. While the first—but not second and third—floors of B. W. Cooper and St. Bernard did flood, the brick-and-cement outer structures and interior plaster walls came through the storm in much better shape than those of much of the city’s flooded private housing stock. The mops and other cleaning material that protestors brought to the April 4 protest underscored that many of the apartments simply needed a thorough scrubbing in order to be made habitable.3 The black women that lived at St. Bernard and other developments were willing and prepared to do the necessary cleaning if only authorities would lift the legal and physical barriers. Yet they were portrayed as lazy “soap opera watchers,” as black city councilman Oliver Thomas smeared them in a calculated attack in February 2006 after an initial rally demanding the reopening of St. Bernard.

The obstacles public housing residents faced were not accidental or due to government foul-ups or inefficiency. Rather, they were intentional and made perfect sense in light of the blueprints drafted by political and economic elites for a new New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. “Those who want to see this city rebuilt,” New Orleans Business Council leader James Reiss explained to the Wall Street Journal only a week after the flood, “want to see it done in a completely different way: demographically, geographically and politically.” Developer Joseph Canizaro was confident the vision of his fellow council member could be realized. “I think we have a clean sheet to start again,” the city’s most powerful developer and a major financial contributor to President Bush told the Wall Street Journal, “and with that clean sheet we have some very big opportunities.” The pronouncements and actions taken by Reiss, Canizaro, and other powerful political and economic actors in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Washington in the immediate aftermath of Katrina made it clear that public housing communities were not part of the “completely different” city they were imagining.4 The city’s public housing communities had faced an unrelenting attack over the three decades preceding Katrina. Yet Hurricane Katrina and the forced displacement of residents provided an opportunity to fast-track the revanchist agenda—to drown public housing in a fully human-made “neoliberal deluge” and finally rid the city of these concentrations of poverty.5 Therefore, it was no surprise that the Bush administration–controlled public housing authority, with full support from the city’s Democratic African American mayor, seized the moment and closed most of the developments immediately after the storm.

But public housing was not the only target of the reenergized revanchist agenda that was spearheaded by state and corporate officials and cheered on by a host of think tanks, academics, and newspaper columnists. The city’s primarily poor, black working-class population, the public sector on which they relied for jobs and services, and the political power this provided were all on the post-Katrina hit list. This unprecedented disaster and the suffering it caused for the survivors would not deter authorities from taking advantage of what former New Orleans city planning director Kristina Ford called a “horrible opportunity … to think about things that in the past were unthinkable” (emphasis added).6 Indeed, the horrible displacement of the city’s poor, black majority was precisely what created the opportunity to carry out the unthinkable—to rapidly and massively impose a neoliberal restructuring plan. This opportunity was at the heart of what Wall Street Journal and New York Times columnists Brendan Miniter and David Brooks, among others, meant when they referred to Katrina’s silver lining.

Therefore, with a silver lining mind-set prevailing among leading government, business, and opinion leaders, it was not surprising that Democratic governor Kathleen Blanco ordered Charity Hospital, the main source of health care for the city and region’s low-paid workforce, closed three weeks after the storm. Blanco and her top hospital administrator, Donald Smithburg, shuttered the impressive art deco 2,000-plus-bed hospital built by the Public Works Administration (PWA) in the 1930s, despite facing little damage and while the Oklahoma National Guard, foreign volunteers, and the hospital’s staff were preparing to reopen it. The governor followed this action by ordering a state takeover of almost the entire 120-plus schools that composed New Orleans’s primary and secondary public education system. With little opposition from the local school board, state authorities fired over 7,000 mainly black teachers and support staff and abrogated their collective bargaining agreement. Of those the state allowed to reopen, most were operated as nonunion, privately run, and publically subsidized charter schools. Not to be outdone, New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin fired over half of the city’s 6,000 mainly black municipal workforce a little over a month after the storm.

This was the hostile political environment that public housing residents and their allies faced in their battle to return home. Government officials and their business partners—whether national or local, Republican or Democrat, white or black—were prepared to employ police repression or flout international law to carry out an agenda author Naomi Klein has termed “disaster capitalism”—the “orchestrated raid on the public sphere in the wake of a catastrophic event.”7 But force, “shock” in Klein’s terminology, was not the only strategy employed in post-Katrina New Orleans to open up sectors, like public housing, schools, and hospitals, that had been closed off to profit making. As political economist Doug Henwood has argued in his critique of Klein’s celebrated work The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, the singular emphasis she places on coercion to explain the post-1973 global imposition of the neoliberal model “skirts the difficult question” of how popular consent and legitimation for this agenda was won.8 Addressing this omission is of particular importance for understanding how the disaster capitalism agenda in post-Katrina New Orleans was imposed and the challenges it generated. Force and coercion were not the only obstacles confronting public housing residents attempting to exercise their right of return. The other, less obvious barrier came in the form of the post-Katrina deluge of foundation-backed nonprofits that helped to consensually introduce the privatization of public housing and other core components of the neoliberal agenda.

The partnership between the nonprofit industrial complex and state and corporate officials to carry out the neoliberal agenda in post-Katrina New Orleans took both direct and indirect forms. The direct variety was the most obvious and transparent. Some nonprofits, such as the New Orleans Neighborhood Collaborative and the Archdiocese of New Orleans’s Providence Community Housing, directly privatized public housing developments in partnership with either another nonprofit or a for-profit corporation. Another variant was the Rockefeller Foundation’s fellowship program that, in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania, assigned young professionals to various nonprofits either privatizing public housing or vying for the opportunity.

The critical indirect role played by nonprofits in facilitating privatization was channeling or “manufacturing”—as Michel Chossudovsky terms it—dissent that did not present a serious obstacle to the post-Katrina neoliberal agenda. This “controlled form of opposition” took various forms.9 One variant was nonprofits and their foundation funders helping to literally construct a nonprofit alternative to public housing and other public services. Nonprofits, whether conventional like Habitat for Humanity or supposedly radical like Common Ground Relief, channeled hundreds of thousands of volunteers into repairing and constructing homes and providing other services rather than incorporating them into a movement to defend public housing and advocate for a public works program to rebuild New Orleans and the gulf. Likewise, Brad Pitt’s much-ballyhooed Make It Right Foundation channeled hopes that Hollywood stars and corporate backers would come to the rescue of the city’s battered Lower Ninth Ward. This initiative, while obviously appreciated by the relative handful that have benefitted, has nonetheless helped to further foster the illusion that philanthropic efforts could rebuild the city. Promoting this illusion—a characterization that will not be negated even if Pitt does eventually deliver on all of the promised 150 homes, none of which are rentals—provided further political cover for the government’s abandonment of this low-income black community.10 Paltry, private initiatives such as these will not reverse the nearly 150,000-person population decline the city suffered between 2005 and 2010. The decline in the black population—118,000—represented over 80 percent of the loss.11

A second form of channeling was through foundations and various levels of government funding a variety of advocacy organizations that narrowly addressed one particular injustice or oppression. This layer of single-issue groups acted as a bulwark against “the articulation of a cohesive common platform and plan of action” to challenge the larger neoliberal agenda in post-Katrina New Orleans.12 The now-defunct Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), for example, which received generous funding from HUD and foundations, did challenge some inequitable policies directed toward low-income neighborhoods, but it studiously avoided any involvement in the struggle to defend public housing. Other foundation-backed nonprofits, when they did get involved in defending public housing, undermined direct action protests and kept the movement from directly challenging the authority of the state to destroy public housing communities.

Despite confronting these hard and soft forms of power, a formidable social movement emerged both before and after Katrina to challenge the neoliberal solution to public housing. How did this movement emerge? What obstacles did the movement confront, particularly from the nonprofits and foundations? And how were they managed? Why did the movement succeed in achieving some goals and not others? What lessons can be drawn from the New Orleans public housing experience for others struggling for an egalitarian urban future? These questions direct the accounts of New Orleans’s pre- and post-Katrina public housing struggles examined in chapters 6 and 7. The story begins in the pre-Katrina aftermath of St. Thomas’s demolition and remaking as River Gardens as a grassroots movement emerged to stymie efforts of emboldened developers to privatize the Iberville public housing development, located just outside the city’s famed French Quarter and main thoroughfare, Canal Street. Chapter 7 concludes two and a half years after Katrina as the dust—both figuratively and literally—settled on years of protest and the demolished remains of some five thousand little-damaged and badly needed public housing apartments. At the same time, the over eight hundred red brick apartments at Iberville, despite intense pressure from developers and government officials, continued to provide affordable housing for low-income Katrina survivors.

I was a leading participant in the pre- and post-Katrina public housing defense campaign analyzed in these chapters, and therefore, I write about my own involvement where needed. My participation facilitated my “understanding,” as Leon Trotsky argues in his firsthand account of the Russian Revolution, “not only of the psychology of the forces in action, both individual and collective, but also of the inner connection of events.”13 At particular points in the narrative, I draw on my insider knowledge to provide a detailed account of events in order to elaborate concepts and support and substantiate my broader arguments. Nonetheless, my participation in these events does not relieve me of the necessity to base my analysis on verified documents. Therefore, this account of the 2004–2008 campaign to defend New Orleans’s public housing and the role of nonprofits relies not only on my memory but also on a variety of primary and secondary sources, including my observation notes.

On to Iberville!

By 2003, in the aftermath of St. Thomas’s demolition, the dispersal of residents, and the makeover as River Gardens, New Orleans’s real estate developers, bankers, and assorted entrepreneurs began setting their sights on the Iberville public housing development. In undertaking this initiative, the corporate wing of New Orleans’s black urban regime would have to work with some new public sector partners. Ray Nagin, the city’s fourth consecutively elected black chief executive, now occupied city hall. Nagin, a millionaire former executive with the local Cox Cable operation (a TV, Internet, and phone provider) who was derided as Ray Reagan during the campaign because of his sympathies with the Republican Party, won the 2002 mayoral race. Nagin, like Sidney Barthelemy a decade and a half earlier, was the preferred candidate of the white business elite and, also like the city’s second black mayor, won a first term without garnering a majority of the black electorate.14 There were changes at HANO, as well. In early 2002, the Bush administration broke the accord that Mayor Morial had crafted with a cooperative Clinton White House to maintain local control over HANO and imposed a series of HUD-appointed administrators to run the agency. Despite the change of faces, electoral coalitions, and political party affiliations, these public officials were as eager to enter into public–private partnerships to redevelop Iberville as their predecessors had been with St. Thomas.

There were other similarities between the Iberville and St. Thomas cases. Iberville was also located in highly valued real estate—in this case, just outside New Orleans’s old-city tourist destination the French Quarter and a block away from the Crescent City’s major thoroughfare, Canal Street. As with St. Thomas, developers and local officials were crafting grand schemes for redeveloping the entire area, with the removal of Iberville being critical to their vision. For example, in 2003, Mayor Nagin commissioned the Downtown Development District (DDD)—a Business Improvement District established by the Louisiana state legislature in 1974, whose board was dominated by real estate interests—to oversee the preparation of a new vision and implementation strategy for redeveloping Canal Street. Released in early 2004, the plan called for incentivizing the creation of upscale housing and new hotels, attracting high-end retailers, expanding an existing medical/biotech corridor, and creating a family-friendly entertainment district. Just as Canizaro’s aid had designated a low-income, black public housing community as, quote, a “deterrent to development” along the riverfront, so did those attempting to “revitalize” Canal Street. “The presence of the Iberville Housing Development has had a profound [negative] effect” on Canal Street, lamented the authors of the Canal Street Vision and Development Strategy, a report subsequently endorsed by the DDD and the mayor. “A high concentration of households with low to very low incomes … and welfare dependence,” the report went on with a litany also reminiscent of St. Thomas, “has proven a formula for community instability throughout urban America, and New Orleans with Iberville is no exception. Fear of crime, generated either by those who live there or those who prey on its residents, has had negative impacts in all directions.”15 Not to be overshadowed, Pres Kabacoff came out with his own revitalization plan in late 2004, with its recommendations mirroring, with a few additions, those made in the DDD-commissioned report. Just as with the DDD study, Kabacoff held that “the single most important linchpin to making this happen”—to realizing his “vision of the city” along Canal Street—was dealing with Iberville.16 To solve the Iberville problem, both Kabacoff and the DDD drew on the tried-and-true St. Thomas formula—a mixed-income, privately run development that would slash the number of public housing apartments and drive out most residents. The black, low-income Iberville community had to go, but it would have to be done, as Canizaro’s aid Nathan Watson emphasized at St. Thomas, in an “efficient” (i.e., consensual) manner. “Controversy,” Kabacoff stressed, “will derail any discussion of rebuilding Iberville” and had to be avoided at all cost.17

Hands Off Iberville

In 2004 as the drive to redevelop Iberville gained steam, local antiwar organization Community, Concern, Compassion, better known as C3, initiated a campaign in defense of the besieged community. Local activists, including myself, formed C3 after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in New York City and Washington, DC, to resist a U.S. military invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. While opposing the war abroad, activists in this grassroots non-501(c)(3) organization always linked the foreign assault with the domestic war at home on poor and working-class communities. The Iberville struggle offered an opportunity to concretely connect these two fronts. As with many antiwar coalitions around the country, the size of meetings and protests had dwindled by 2004, after the unprecedented mass mobilizations the year before had been unsuccessful in stopping the Bush administration’s drive to invade Iraq. When C3 decided to focus on Iberville (while not abandoning antiwar work), more activists, uncomfortable with taking on public housing, drifted away. A core group, including three white activists—Mike Howells, Marty Rowland, and myself—as well as legendary African American civil rights activist Andy Washington, continued on. At the same time, as C3 expanded the issues it addressed, the organization became more diverse as more female, African American, and low-income members began participating. These new activists included a white woman, Elizabeth Cook, black community activist Randy Mitchell, and three black Iberville residents—Cody Marshall, Delena Moss, and Cary Reynolds. These eight to nine activists, constituting the core of C3 before the storm, were regularly joined by a wider group of public housing residents, students, and other community activists for the group’s weekly meetings and protest actions.

The first action where C3 explicitly drew parallels between the wars abroad and at home was during the March 2004 demonstrations marking the first anniversary of the Iraq war. C3 activists led a march that stopped at the local public hospital—Charity—and Iberville to highlight how the United States was simultaneously leading a war of pillage in Iraq for oil and one at home against public services. The other core C3 members and I performed outreach work, before and during the march, to Iberville residents in order to show support for defending the development and opposing demolition or any loss of units.18

After Pres Kabacoff announced his own grand plans for Iberville in late 2004, C3 decided to prioritize the defense of Iberville. Taking advantage of the power embedded in public housing’s geography, I secured the St. Jude Community Center to hold C3 meetings, conveniently located for Iberville residents only a few blocks from the development. C3 activists, as part of their outreach, began regular leafleting and door knocking at Iberville to explain their support for defending Iberville and invited tenants to the weekly meeting to help organize a movement in defense of the community that would unite residents and nonresidents, blacks and whites. Invitations were also given to the tenant council to join the defense campaign. Iberville tenant council president Ollie Pendleton did not accept the offer, but she did begin to monitor the gatherings by standing at a nearby street corner to observe, argued Iberville residents, who and how many of her constituents were attending. Citywide public housing tenant council president Cynthia Wiggins—who by the mid-2000s was drawing a comfortable salary of over $70,000 as CEO of the nonprofit corporation that managed the Guste public housing development—was invited, as well, but never returned phone calls.19

The first public demonstration taken by C3 activists and supporters since placing Iberville at the center of their work was on February 12, 2005. Under the new name C3/Hands Off Iberville, which underscored the group’s forceful and unapologetic defense of public housing, a few dozen protestors gathered in front of the development. Led by Iberville tenant Delena Moss, activists challenged the common sense that Iberville would follow the same fate as St. Thomas. Moss, others that spoke, and I called for not only saving Iberville but recovering the thousands of public housing units lost over the last decade. In contrast to the St. Thomas experience, where nonprofits helped mask the contradictory class and race interests at play in public housing redevelopment, the grassroots, non-foundation-supported Hands Off Iberville worked to make them transparent. Instead of being cowed by developers and city hall and accommodating to the neoliberal reform agenda, it was defiant and announced support for defending and expanding public housing. The initial demonstration, in addition to attracting new members, including Iberville resident Cody Marshall, helped create the controversy so feared by developers by making it clear there was a pole of opposition to demolishing Iberville. A free local newspaper geared toward the black community, Data Weekly, helped fuel the controversy by emblazoning “Hands Off Iberville: The Community Strikes Back” across its entire front page in its coverage of the protest. The local paper of record, the Times-Picayune, a longtime supporter of public housing demolition, did not cover the protest. Instead, two days after the rally, New Orleans’s only daily newspaper came out with a front-page article in the metro section that appeared designed to quell the brewing controversy by placing redevelopment in a positive light. The article, entitled “HANO to Start Housing Blitz,” touted the new housing that would be shortly built at four demolished public housing developments.20

Throughout the winter and spring of 2005, C3 continued to use various venues and forums to denounce attempts to demolish Iberville and expose the contradictions of New Orleans’s black urban regime. For example, a ten-person C3 delegation spoke at the city council’s televised April housing committee meeting and later, after continual requests and pressure, before the entire council in June. The speakers contrasted their agenda of expanding Iberville and public housing with that of developers, which was described by activist Mike Howells, in a strategic attempt to dramatize the two opposing poles, as one of “ethnic and class cleansing.” Similar messages were regularly delivered at HANO’s monthly board meetings. Activists also organized an April 12 Night Out against Gentrification demonstration in front of a former department store, located near Iberville on Canal Street, that developers were converting into high-priced condominiums.21 Yet in C3’s effort to broaden support for Iberville, the grassroots activists failed to garner the backing of nonprofit groups, even those that identified as activist, antiracist, and prolabor. One of these was Community Labor United (CLU), found and led by a retired African American labor organizer whose ostensible mission was to connect labor unions with community-based struggles for racial and economic justice. Nonetheless, despite repeated invitations, CLU—which at the time was busy obtaining funding for its nonprofit think tank, the Louisiana Research Institute for Community Empowerment (LaRICE)—failed to mobilize support for Iberville.22 The group INCITE! Women of Color against Violence, which held its third Color of Violence conference in New Orleans in March 2005, also declined an invitation, made by a young African American women active in C3, to route their planned march to Iberville. C3 argued that the attack on Iberville was a concrete, local expression of structural violence directed against primarily African American women and would be an ideal way for the organization to connect with local struggles. INCITE!, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit at the time, was not swayed.23

C3’s last major initiative before floodwaters swamped the city was spearheading the defeat of a HOPE VI application for Iberville. In late May a local legal aid attorney sent me an email explaining that the new HANO director, Nadine Jarmon, despite earlier assurances to the contrary, was planning to submit a HOPE VI application for Iberville. But before submitting the required annual Public Housing Agency Plan to HUD—which outlined the agency’s plans for Iberville and other developments for the 2005–2006 fiscal year—HANO had to hold a hearing at the end of June to take public comment. HANO could then revise its plan in the light of public feedback before sending it to Washington, DC, in mid-July.24 Over the next month C3 members, including tenants Delena Moss, Cary Reynolds, and Cody Marshall, mobilized through phone calling and door knocking to inform residents and supporters about HANO’s plan and encourage attendance at the crucial June 30 hearing. As part of a strategic effort to expose collusion between developers and public officials and increase the controversy that developers wanted to suppress, I handed, during my testimony before the city council on June 16, a public records request to city councilwoman Jacquelyn Clarkson, whose district encompassed Iberville. I demanded at the televised hearing that she come clean about her meetings with developers. After Clarkson produced the documents, C3 distributed a flyer exposing the meetings she had concerning Iberville with HRI CEO Pres Kabacoff and his top lobbyist, former mayor Barthelemy.25

Although little headway had been made getting nonprofits on board the campaign, on June 30, dozens of grassroots activists, including key Iberville resident leaders Cary Reynolds, Delena Moss, and Cody Marshall, descended on the HANO boardroom. The HANO police—a force that dramatically expanded as the agency simultaneously downsized its housing stock in the 1990s and 2000s—ordered protestors to discard their placards before entering the building. These heavy-handed tactics, far from squelching the protestors, seemed to only raise their ire further as a series of speakers rose to the mic to denounce any plans to demolish Iberville. Delena Moss exposed the class issues at stake: “It’s about the land. They’re trading lives for money.” Creating controversy worked. Officials were put on the defensive, as they claimed—in contradiction to their written report—that they had no plans to demolish Iberville. Jarmon, in a subsequent mid-July meeting with C3, agreed to eliminate the HOPE VI request from the annual plan. Carmen Valenti, who acted as HANO’s one-person HUD-appointed board, tried to defuse the situation by portraying the HOPE VI plans for Iberville as a misunderstanding: “It should have never been included in the agency’s plan. It caused some embarrassment.”26

Is There an Alternative? Lessons from Iberville

While the defeat of the HOPE VI application by no means permanently protected the Iberville from the designs of developers, it nonetheless was an important poor people’s victory. HANO’s decision validated both Pres Kabacoff’s concerns that controversy could derail his redevelopment initiative and, conversely, the hopes of grassroots activists that, in contrast to the reigning TINA ideology, their efforts could have an impact. Other urban scholars have found, as well, a rational basis for both concern and hope regarding contemporary urban redevelopment initiatives. As sociologist Joe Feagin argues, neoliberal policies such as demolishing public housing “do not develop out of an inevitable structural necessity but rather in a contingent manner. They result from conscious actions taken by individual decision makers.” The actions taken by local government and corporate decision makers are, adds Pauline Lippman, “conditioned by the relative strength and mobilization of social forces (e.g. organizations of civil society, working class organizations, popular social movements) and the political culture of specific contexts.”27

What helped create the popular mobilization and power at Iberville that Lippman identified as crucial for defeating contemporary urban neoliberal initiatives? A key source of the movement’s power was the freedom that came from activists operating outside the nonprofit complex. This independence enhanced the ability to forge power from below to challenge the urban neoliberal agenda in two ways. First, as an independent, grassroots organization, C3 was not limited to issues outlined in grant applications or constrained by directives of foundation officers. Operating outside the government-sanctioned and foundation-funded third sector provided the organization the freedom to democratically decide what organizing campaigns to initiate and when. This independence allowed activists to quickly respond to moves by developers and state officials rather than wait for permission from funders or for the following year’s grant cycle. Furthermore, independence from foundations provided the flexibility to move beyond single-issue activism and begin to connect, theoretically and concretely, with other struggles. As Michel Chossudovsky has argued, corporate funding of advocacy groups tends to “fragment the people’s movement into a vast ‘do it yourself ’ mosaic,” and as a result “dissent has been compartmentalized. Separate ‘issue oriented’ protest movements (e.g. environment, antiglobalization, peace, women’s rights, climate change) are encouraged and generously funded as opposed to a cohesive mass movement.”28 In contrast, the Iberville campaign was able to move beyond these strictures and build greater power by linking the war abroad to cuts in social programs at home and the activists involved in these struggles.

The second source of strength that arose from C3’s organizational independence from the nonprofit complex was that it allowed the group to undertake an aggressive campaign that could exploit the race and class contradictions of the black urban regime’s development agenda. The elite’s attempt to privatize Iberville and displace this low-income black community was a clear manifestation of the accumulation–legitimation contradiction at the heart of the black urban regime. A critical source of power for working-class organizations therefore is their ability to highlight and exploit this pressure point within the local power structure. As Mark Purcell argues, neoliberal regimes “creak under their contradictions,” but he adds, “it takes active, organized, and committed resistance to bring about a collapse.”²29 Nonprofits, as analysts have noted, are, however, ill equipped for this job, tied as they are to a “pragmatic” agenda of “reasonable goals” obtained through “negotiations with state officials via sympathetic politicians.”30 In contrast, the grassroots Iberville insurgency, though not having large numbers, nonetheless had the political and financial independence to use various terrains—from HANO hearings and televised city council meetings to street protests and press conferences—to dramatically and forcefully expose the regime’s class and race contradictions. A final strength the Iberville movement enjoyed arose from the political-geographic organization of residents in public housing. The concentration of residents in one geographic area, under a single state authority, facilitated organizing and collective consciousness. This source of power took a major blow, however, a little over a month after the poor people’s victory at Iberville when Hurricane Katrina roared into the Gulf Coast.

Public Housing and Hurricane Katrina

For many low-income African Americans in New Orleans, public housing historically provided not only a source of affordable housing but hurricane protection, as well. With over a third of the city’s African Americans living in poverty and without cars, the costly privatized evacuation system was not a realistic option. Thus, as Katrina approached many of the poor turned once again to the city’s two- and three-story brick-and-cement public housing buildings for protection. The “bricks” successfully spared them, as they had in the past, from the Category 2 hurricane that hit New Orleans on August 29, 2005. Then, after floodwaters breached the federal government’s inadequately maintained levees—dramatically unmasking just one piece of the country’s severely eroded infrastructure—public housing became a secure base for residents to organize an evacuation after their abandonment by all levels of government. As St. Bernard resident Gloria Irving explains, “I was on the third floor with my flag waving for them, but they never stopped,” in reference to helicopters circling the city. “They were passing by, but they didn’t help anybody.” It was “our men,” Irving and other survivors explain, who “were our heroes.”31

Irving’s firsthand account of post-Katrina New Orleans contrasts sharply with reports that emanated from mainstream media outlets at the time of the disaster. The airwaves were filled with unsubstantiated reports of black men carrying out rapes and other atrocities at the convention center and the Superdome, the city’s two main evacuation centers, and shooting at rescue helicopters, while attempts to obtain food, water, and other necessities were indiscriminately labeled “looting.” These claims of wanton violence, which were later debunked, were also given credence by the city’s African American mayor, Ray Nagin, and police chief, Eddie Compass. Before national and international audiences in the week after Katrina, they repeatedly reported that “hooligans” among the overwhelmingly black survivors at the Superdome and convention center were beating, killing, and raping people.32 Governor Kathleen Blanco furthered the demonization and criminalization of survivors as she hailed the “landing” in New Orleans of “troops fresh from Iraq, well trained, experienced, battled tested.” As she coldly announced, “[The troops] are ready to shoot to kill, and they are more than willing to do so if necessary, and I expect they will.”33 While this vilification campaign was going on, the African American men at St. Bernard were helping ferry children and the elderly from the St. Bernard development to a nearby highway overpass at a time when authorities had effectively abandoned these folks. Most had to wait for days, camped out on the asphalt and under the broiling sun, before finally being evacuated. Many, to the chagrin of former first lady Barbara Bush, ended up in Houston.34

While St. Bernard and other public housing residents were dealing with their trauma, tracking down loved ones and figuring out where they could obtain food and housing, their affluent city brethren had other concerns. They were busy gathering, as Wall Street Journal reporter Charles Cooper entitled his September 6 article, to “plot the future” of the city. Joseph Canizaro was, of course, at the center of these deliberations. Members of the New Orleans Business Council—with Canizaro calling in orders from his vacation home in Utah—met in early September with Mayor Nagin in Dallas to lay out a post-Katrina framework for reconstructing the city. Out of this and subsequent meetings and discussions came the Bring New Orleans Back Commission (BNOB), which the mayor authorized to develop a rebuilding blueprint. Canizaro sat on the BNOB’s critical urban planning committee. Barbara Major, another familiar face from St. Thomas and close associate of Canizaro, was named—ostensibly by the mayor—as the BNOB cochair. In another page from St. Thomas, the first decision of the seventeen-member BNOB was to invite the Urban Land Institute to develop a plan delineating which parts of the city should be rebuilt. The ULI experts called for a “smaller footprint” through “green spacing”—not rebuilding—certain sections of the city. These areas overwhelming were black neighborhoods.35

Like the BNOB, a variety of activists also began, in the wake of the storm, to plot the challenging of the closure of public housing, the green spacing of other low-income neighborhoods, and a range of other regressive plans then being rolled out. Nonetheless, the post-Katrina landscape presented serious obstacles to C3’s resuming their defense of Iberville and other public housing communities. Cody Marshall had taken a job with a cruise line before the storm (he would later return), while Delena Moss and Randy Mitchell decided not to return to the city, and it would be several years before Cary Reynolds reappeared. Andy Washington, Marty Rowland, and I had evacuated, although within the first few months we were back periodically and were in regular contact with each other, as well as folks in New Orleans. Thus in the first few weeks and months after the storm, much work fell on Elizabeth Cook, who lived in the city’s unflooded west bank and returned home shortly after the storm, and Mike Howells, a holdout who never evacuated. They took the lead in challenging the claim made by HANO officials and repeated by the Time-Picayune that the developments, including Iberville and Lafitte, both of which received little flooding, were “ruined,” “decimated,” and “not habitable” and, thus, could not be reopened.36 They took photos of Iberville and other developments showing that the buildings faced little or no damage and could be reopened. On September 10, Howells led Amy Goodman, the host of the nationally syndicated radio show Democracy Now, and journalist Christian Parenti of the Nation to the Iberville to show the little damage it had incurred.37 In addition, both Cook and Howells regularly went to the developments to meet residents who were returning to check on their belongings.

In contrast to the frequent claims in the mainstream press that most poor African Americans had no interest in returning, Cook and Howells repeatedly encountered residents who desperately wanted to return home. For example, Cook met future public housing activist Sam Jackson while he was visiting his apartment at the B. W. Cooper development in October. She worked with Jackson to organize a press conference to underscore that he and his family wanted to return and for HANO to stop blocking them. In addition, they called upon local authorities to end the looting of public housing families’ apartments, which plagued New Orleans after it was reopened in mid-September.

Though C3 activists demanded the reopening of all public housing developments, their efforts in the first few months after Katrina centered on Iberville. Residents were on the front lines of this struggle as many took direct action to reclaim their homes. For example, one couple, Paul and Shantrel Martin, moved back with their children and used a generator to provide electricity, since HANO had cut off utilities in an effort to keep people out. Even an eighty-plus-year-old resident, whom C3 activist Marty Rowland assisted, was one of several Iberville residents who reoccupied their homes without official permission. As in the past, C3 used public forums, including the city’s first post-Katrina city council and HANO meetings, both held in October, to vociferously call for the reopening of public housing and to offer counterarguments to those used to justify its continued closure.

By early October Howells and Cook had resumed the weekly Thursday public housing meeting, and they eventually returned it to the St. Jude Community Center. The group was then joined by other activists, including some connected to the Peoples Hurricane Relief Fund (PHRF)—the successor organization to Community Labor United—and Common Ground Relief, a group formed after the storm by former Black Panther Malik Rahim. Common Ground was a nonprofit that attracted volunteers from across the country and world to provide a number of services for Katrina survivors, from a free health clinic to house gutting and repair to the development of organic gardens and the opening of a low-income apartment complex. While the bulk of their efforts, as I critique later, were directed toward self-help and nongovernmental social service efforts, some of the young people involved with the group did get involved in the defense of public housing and renters’ rights. C3, Common Ground, the PHRF, and other activists helped form the new housing coalition New Orleans Housing Eviction Action Team (NO-HEAT). The group focused on reopening public housing and stopping the post-Katrina evictions of private sector renters by landlords trying to get higher-paying tenants as rents soared after the storm. On December 3, NO-HEAT held a march in front of Iberville demanding the reopening of public housing. Shortly afterward, the movement won its first major victory when HUD announced it would reopen Iberville. The controversy created before Katrina, the protests after the flood, and the direct action taken by residents had forced HUD’s hand. As Iberville resident Annette Davis puts it, HUD “wanted to keep the low-income people away” and give Iberville to developers, but because of the protests and media attention, officials “got scared” and “gave in.”38 As the late Rev. Marshall Truehill, a politically connected black minister with access to the mayor, confirmed, “[C3’s] protests made a difference.” Also important, the protests impacted the calculations of HUD secretary Alphonso Jackson, who had the final say on reopening Iberville. Underscoring the extent to which the pre- and post-Katrina public housing movement had created a controversy around Iberville that raised the political costs of keeping it closed, Jackson told housing advocate James Perry that “I know people want to do [Iberville] as a land grab, and it’s not going to happen on my watch.”39

Nonprofits, Identity Politics, and Ideological Struggle within the Public Housing Movement

As the new year began, the housing movement celebrated some victories, including the reopening of Iberville and the defeat of the BNOB’s green-spacing scheme to block the rebuilding of mainly black neighborhoods. Vehement denunciation of the proposal and Joe Canizaro—who led the BNOB’s urban planning committee, which unveiled and advocated the plan—forced Mayor Nagin to withdraw support for the initiative.40 Nonetheless, despite these victories four other traditional developments (St. Bernard, Lafitte, C. J. Peete, and B. W. Cooper), hundreds of scattered-site units, and two Ninth Ward developments (Florida and Desire) that had been turned into mixed-income communities before the storm remained closed. Furthermore, with most public housing residents now scattered across the state and country and federal and local authorities intent on taking advantage of their displacement in order to rid the city of these concentrations of poverty, the obstacles confronting NO-HEAT’s efforts to reopen public housing were formidable. In addition to these external challenges, internal ideological conflicts, rooted in questions of legitimacy and identity, confronted and divided the city’s post-Katrina public housing/right of return movement. C3 activists, as they had before the storm, emphasized the importance of an interracial class struggle and confrontational strategy, what William Sites has called the “militant” or “community resistance” tendency in neighborhood and community battles.41 C3 combined calls for reopening public housing developments, public schools, and Charity Hospital with a larger demand for a mass, direct-government employment program, funded by ending foreign wars and taxing the wealthy, to rebuild New Orleans, the Gulf Coast, and the entire country.42 With the displacement of most public housing residents, Mike Howells argues, “It was more important than ever for white and other non–public housing folks to raise their voices.” In contrast, some activists, usually those affiliated with nonprofit organizations, criticized white members of the multiracial C3 for taking a lead role in the public housing movement. For example, Mayaba Liebenthal, an organizer with Critical Resistance, a nonprofit prison abolitionist group, argues in a March 2006 posting on the NO-HEAT Listserv that “the white folks at C3 need to back off.”

Dealing with racism isn’t your life’s experience, I would never presume to speak on behalf of white people, could one of you show me and other people of color the same respect …. This habit on speaking on behalf of those “less fortunate” is becoming more than just comically irritating but offensive and damaging to actual change … for me this [is] about very practical issues, organize from where you personally and actually are.43

An antiracist trainer with the People’s Institute disrupted a March 2006 C3 meeting to level a similar criticism. Liebenthal’s critique articulates central elements of identity politics, a postmodernism-informed worldview and theory of organizing that has risen in tandem with neoliberalism. Exponents of identity politics place emphasis on “differences as the central truth of political life” and therefore stress, to cite Liebenthal’s manifesto, organizing “from where you are.”44 That is, organizing should be based on a particular racial, gender, sexual orientation, ability, or other oppression (or privilege, depending on where you stand). This form of organizing is rooted in a key epistemological assumption of identity politics that “only those who actually experience a particular form of oppression” are able to understand and fight against it. Thus if, as Liebenthal explains, “racism isn’t your life experience,” if you don’t “actually experience a particular form of oppression,” then you are not “capable of fighting against it.”45

With most public housing residents still in exile, Liebenthal and other identity politics advocates effectively were demanding quiescence while authorities proceeded to demolish the homes of low-income, black Katrina survivors. In fact, if identity politics logic is followed consistently, even African Americans who were nonetheless not public housing residents, such as Liebenthal, would not have had the legitimacy required to take a leading role. The following critique by political scientist Adolph Reed captures the demobilizing impact the identity politics debate had on the public housing movement:

[Identity politics’s] focus on who is not in the room certainly does not facilitate strategic discussion on how best to deploy the resources of those who are in the room, and its fixation on organizing around difference overtaxes any attempt to sustain concerted action.46

As was the case in New Orleans, the immobilizing debates on legitimacy, identity, and difference undermined attempts to assemble the resources activists did have to confront the powerful forces bent on doing away with public housing and all public services.

It was not surprising that an identity politics critique of the public housing movement emanated from the nonprofit world. This milieu provides, Joan Roelofs argues, a “fertile soil” for the promotion of an IP form of organizing that focuses on a particular oppression, with only those most directly impacted eligible to participate. While identity politics ideology did strike a chord with the nonprofit sector, it did not enjoy much resonance among public housing residents. In fact, in late January 2006 several displaced St. Bernard public housing residents then living in Houston began calling C3 activist Elizabeth Cook after finding her number on an Internet post announcing a Martin Luther King Jr. Day march that the public housing movement had organized from the Lower Ninth Ward.47 They desperately wanted to return home. After several weeks of networking with residents, I was designated by C3 members to take a bus to Houston, rent a van, and bring back the residents for a Valentine’s Day action to demand the reopening of the development.

A brief discussion of my experience organizing the trip helps elaborate the opportunities and constraints confronting antineoliberal challenges that operate outside the nonprofit sector. On one level, independence from the nonprofit complex provided flexibility on what issues C3 addressed and the tactics and strategies employed. Yet operating outside the reach of the foundations left activists bereft of the financial support that was at times needed for organizing. To address this contradiction, I reached out for support from various Left activists based in Houston who had been involved in post-Katrina solidarity work. Activists with the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), whose party members have been active in other cities, particularly Chicago, in defense of public housing, were the only group that responded to my request.48 I was picked up in the bus station by an RCP member and brought to the airport, where I rented a van. Again, since C3 had no significant financial resources, I charged the rental to my credit card with the expectation that we would then raise money to get reimbursed. I then followed my guide to the apartment complex in south Houston where I had arranged to pick up the residents. About ten displaced women from St. Bernard, including seventy-year-old Gloria “Mama Go” Irving, who had called me repeatedly to confirm that I would pick her up, boarded the van in the early hours of February 14 for the six-hour ride through the Louisiana bayou and back to New Orleans.

We arrived in the early afternoon for what C3 dubbed the Have a Heart, St. Bernard Must Restart rally and press conference. Among those in attendance was antiwar activist Cindy Sheehan, who helped connect the antiwar and the New Orleans right of return struggles by pointing out the contradictions between the resources spent on the war in Iraq and the lack of support for low-income Katrina survivors. St. Bernard residents Gloria Irving and Stephanie Mingo, depicted in figures 6.1 and 6.2, made it clear they wanted to return home. Their moving but forcefully delivered message broke through the dominant narrative, propagated in various human interest stories of displaced New Orleanians, that the city’s poor had found opportunity in the diaspora and had no desire to return to their impoverished city.49 The response of the African American political leadership to their pleas was, though, to either place responsibility for the matter in HUD’s lap or denigrate public housing residents as unworthy burdens that the city could not accommodate. “We don’t need soap opera watchers right now,” bellowed Councilman Oliver Thomas at a city council meeting a few days after the rally as Stephanie Mingo called for reopening St. Bernard. This African American Democrat conjured up the racialized and gendered welfare queen stereotype, pontificating that “we’re going to target the people who are going to work … at some point there has to be a whole new level of motivation, and people have got to stop blaming the government for something they ought to do.”50 HANO responded to resident’s pleas by placing a metal fence, topped by barbed wire, around the development.

Despite these attacks, the movement to reopen public housing—the closure of which crystallized the class and race biases of what historian Lance Hill calls the post-Katrina “exclusionary” agenda—began gaining traction. Endesha Juakali, a former chair of the HANO board who grew up at St. Bernard, joined the fight to reopen his childhood community after the February 14 protest. Juakali, as explained in chapter 2, had lent support, as HANO chair in the late 1980s, for Reynard Rochon’s plan to massively downsize public housing. Nonetheless, Juakali, in the aftermath of Katrina, supported the demand to reopen all apartments at St. Bernard and other developments. At a C3 meeting in late March, Juakali proposed that activists organize a caravan of displaced residents from Houston for an April 4—the anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination—action to force the reopening of St. Bernard. C3 members endorsed the plan, and I volunteered to join Juakali for this second Houston mission. After four days of phone calls and meetings, with Gloria Irving’s apartment serving as an organizing center, we joined thirty or so residents in two vans and several cars in a caravan back to New Orleans. To cover the costs, Juakali and I turned for help from the PHRF, an organization

that emerged after Katrina as the successor to the CLU. The PHRF, whose donations were routed through its 501(c)(3) fiscal sponsor, the Vanguard Foundation, had raised over a million dollars after the storm. In contrast to other nonprofits, the PHRF saw itself as spearheading a radical grassroots fight for the right of return and against the racist exclusionary agenda. Nonetheless, the PHRF’s leaders, Malcolm Suber and Kali Akuno, who were then in the midst of a nasty internal fight with a faction led by CLU founder Curtis Muhammad that would lead to a splinter group, did not deliver on our request. Therefore, I was forced to charge the costs of two vans and a car rental to my credit card and hope, as happened in the last trip, to be reimbursed through subsequently collected donations.

The April 4 attempt by St. Bernard residents to reclaim their community and the repressive response this generated graphically exposed the contradictions of New Orleans’s black urban regime and the U.S. state. On the anniversary of King’s death, the locally controlled police and federally directed HANO cops lined up to physically block attempts by displaced black women and their families—and their black and white supporters—to clean and reclaim their apartments. The phalanx of police contrasted sharply with both the claims of the local black leadership to be a defender of the black community and that of the U.S. state to be the beacon of human rights. Residents and activists were undeterred by the show of force. Armed with mops and brooms and led by the wheelchair-propelled Gloria Irving, marchers burst through the police lines and entered into the development. Residents proceeded to go into their apartments and collect personal items and mementos, and although they were not ready to mount a permanent reoccupation, they vowed to return. The pace of events accelerated as the bold action taken by St. Bernard residents spurred on others. In late April, C3 led a march of Iberville residents to the local HUD office to demand quicker action on reopening apartments and addressing a myriad of other problems tenants faced. Then, on May 3, hundreds of residents and supporters converged to shut down the monthly HANO meeting, declaring there would be “no business as usual” until the people came home.

The new offensive proposed by Juakali was to launch a Survivors Village tent encampment in front of St. Bernard and his nearby home and office. By this time, the NO-HEAT coalition had collapsed, but activists with C3 and Common Ground enthusiastically supported Juakali’s plan and helped clean his home of debris as part of the preparations. The encampment, which was to open on Saturday, June 3, would be used as an

organizing base to push for the reopening of St. Bernard. Indeed, as the event neared, Juakali announced the June 3 action would culminate with a march and reoccupation of St. Bernard. Residents were emboldened and ready. “Guess what?” declared St. Bernard resident Karen Downs while addressing the city council housing committee a few days before the weekend launch of Survivors Village, “Saturday and Sunday, we’re going to tear it [the fence] down.” The pressure from below was even forcing conservative citywide tenant leader Cynthia Wiggins to make bold pronouncements, as she declared at the same city council meeting: “Come June 3rd, we’re not going to wait …. We’re going to move forward to getting our complexes open.”51

Spirits were high as the movement approached a potential turning point. As civil rights historian Lance Hill wrote at the time, “The elite group that engineered the plan to prevent the poor from returning” had been able to carry out this agenda, until now, “without fear of social disruption or civil disturbances.” The June 3 action promised to change this

calculus, as residents were, Hill observed, ready “to defy the law and take back their homes.”52 Of course, there had been protests, police clashes at St. Bernard, and individual, unauthorized reoccupations at Iberville, but June 3 promised to ratchet up considerably the level of disruption against the silver lining agenda. It was not to be. As residents and supporters marched to the development on June 3, Juakali unilaterally decided that the march would not, as previously announced, culminate with an occupation. A larger march on July 4 was also ordered to stop short of retaking the community. When the public housing movement did not follow through on its promises, HUD retook the initiative. On June 14, HUD secretary Alphonso Jackson announced that the four remaining traditional developments—St. Bernard, Lafitte, C. J. Peete, B. W. Cooper—would be demolished and transformed into mixed-income communities along the lines of St. Thomas. Jackson reassured participants in the teleconference announcing the decision—one lauded by Mayor Nagin—that “public housing [residents] will be welcomed home.”53 This promise—one

that public housing residents were used to hearing but was infrequently fulfilled—was belied by the rebuilding numbers submitted by developers subsequently selected by HUD. Of the over 5,000 public housing apartments at the four original developments, developers planned to rebuild only 669 in their new mixed-income communities.54 In another contradiction that further raised skepticism among residents, authorities claimed their redevelopment plans were designed to deconcentrate poverty, yet they failed to reopen hundreds of the smaller scattered site apartments built three decades earlier with that very goal.

Nonprofits and Privatization

A few months after the June 2006 demolition announcement, HUD began awarding contracts to redevelop public housing. These contracts went, unsurprisingly, to for-profit developers such as McCormack, Baron, and Salazar, whose CEO, Richard Baron, sat on the 1989 national commission that laid the groundwork for HOPE VI. Baron’s outfit won the contract to redevelop C. J. Peete, with Goldman Sach’s Urban Investment Group acting as the major investor.55 But nonprofit organizations were included, as well. For example, HUD named the New Orleans Neighborhood Collaborative (NONC)—headed by Orleans Parish school board member Una Anderson, who fully supported the post-Katrina dismantlement of the public school system and collective bargaining—as a partner with McCormack and KAI architects to lead the redevelopment of the C. J. Peete complex. Providence Community Housing, an arm of the Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans, received the contract to oversee the redevelopment of the Lafitte public housing complex.

New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff termed the demise of the little-damaged 900-unit Lafitte complex—with its “handsome brick facades, decorated with wrought-iron rails and terra cotta roofs” built by WPA-employed Creole artisans and modeled after the French Quarter’s 1850s-era Pontalba apartments—“a human and architectural tragedy of vast proportions.”56 Partnering with Providence in this tragedy was Enterprise Community Partners, who operate on a national level, providing “capital and expertise for affordable housing and community development” initiatives.57 The collaboration at the neighborhood level by the nonprofit Ujamaa Community Development Corporation, run by an activist priest at the local Catholic parish, and the embracing of the plan by Emelda Paul, the head of the tenant council, and Leah Chase, a civil rights veteran and owner of the landmark restaurant Dooky Chase, located next to Lafitte, provided a grassroots veneer to the initiative. The actual selling of the Lafitte redevelopment was a classic example of what Michelle Boyd has called the “Jim Crow nostalgia” approach to gentrification. Redevelopment was framed by neighborhood elites and their foundation and church backers as a way to recapture an idealized, racially unified, “authentic” blackness from the neighborhood’s past. This packaging helped obscure the reality of an elite-driven “economic development strategy that ultimately privileged homeowners over low-income and public housing residents.”58

Other nonprofits connected to the Lafitte initiative even included ostensible defenders of public housing. For example, Shelia Crowley, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), whose organization receives generous funding from large foundations and banks, served on the board of trustees of Enterprise, a key player in the Lafitte plans. During a weekly conference call coordinated by the National Housing Law Project and with participants from the NLIHC and other national and local housing advocates, C3 activist Elizabeth Cook and I repeatedly called on Crowley to denounce Enterprise’s role in demolishing Lafitte and to resign from the board if they refused to pull out. Neither Crowley nor key staffer Diane Yentel—who represented NLIHC on the calls and later went on to work in HUD’s public housing division under the Obama administration—even deigned to respond to these repeated requests.59

The AFL-CIO’s investment arm, the Housing Investment Trust (HIT), also wanted to participate in the Lafitte redevelopment, but when the Archdiocese’s Providence Community Housing refused to use union labor, they pulled out. The following year in the spring of 2007, HIT teamed up with a recently formed nonprofit that Survivors Village leader Endesha Juakali helped form—the St. Bernard Housing Recovery & Development Corporation—to obtain the contract to redevelop St. Bernard. Unfortunately for the AFL-CIO bankers and Juakali, HUD had no intentions of nixing the deal they had already made with the nonprofit Bayou District Foundation and their development partner, Atlanta-based Columbia Residential, which enjoyed close business ties to HUD secretary Jackson.60 Though unsuccessful at winning the contract, Juakali’s nonprofit initiative did succeed in pulling residents for a time toward insider negotiations, as happened at St. Thomas, and away from the terrain of protest where they could exercise power.

The Rockefeller Foundation Redevelopment Fellowships program, which was administered by the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Urban Redevelopment Excellence (CURE), also buttressed privatization of public housing. Fellows were assigned to various for-profit and nonprofit corporations involved in privatizing New Orleans’s public housing, including Enterprise, NONC, Urban Strategies, Providence Community Housing, Columbia Residential, and HIT. CURE was an appropriate interlocutor for the program, with their board of directors filled with private and public sector officials who played major roles in dismantling public housing. This list included developer Richard Baron, as well as Bruce Katz of the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Division, who promoted and oversaw HOPE VI redevelopment schemes as a high-ranking Clinton HUD official in the 1990s. The well-known and then New Orleans–headquartered community organization ACORN also received several fellows. Though not directly involved in privatizing public housing, the organization studiously avoided any contact with the antidemolition movement. Contributing to this reticence must have been the almost $1 million in grants ACORN obtained from HUD—the agency ordering and overseeing demolition—for work in post-Katrina New Orleans.61

In addition to ACORN, a whole host of nonprofit, foundation-funded advocacy, or activist, organizations either emerged or expanded in the aftermath of Katrina to address various social justice issues related to post-Katrina New Orleans. The newly created NGOs included the Peoples Hurricane Relief Fund (the successor to Community Labor United) and a later split off, the People’s Organizing Committee (POC); the Workers’ Center for Racial Justice; and the Louisiana Justice Institute. Preexisting nonprofits that expanded included Advocates for Environmental Human Rights (AEHR), the People’s Institute, and the criminal justice reform groups Safe Streets, Friends and Family of Louisiana’s Incarcerated (FFLIC), and Critical Resistance.62

In addition to the advocacy variety, a slew of nonprofits emerged post-Katrina to provide relief services, from housing to health care, rather than defend public services. These outfits included the well-known home-building nonprofit Habitat for Humanity—which acquired some public housing properties—as well as the locally based St. Bernard Project, which operated in the neighboring parish, not the public housing development, and was founded by two Washington, DC, transplants in 2006.63 Another variant in this direct-service trend was nonprofits founded by self-identified radical community activists who framed their conventional social service work in radical-sounding language. A prime example was, surprisingly, the local chapter of INCITE!, an organization that published an influential book critiquing the conservatizing role of foundations and nonprofits. While nominally supporting the reopening of Charity Hospital, INCITE! activists nonetheless directed most of their energies toward opening a nonprofit health clinic. Common Ground was organized by former Black Panther Malik Rahim after Katrina to provide, as he and his collaborators explained, “solidarity, not charity.” Indeed, some of the youth associated with Common Ground did solidarize and participate in the public housing movement and played a leading role in reopening the Dr. Martin Luther King Elementary School in the Lower Ninth Ward.64 Nonetheless, despite the radical rhetoric, Common Ground funneled most of their volunteers—mirroring how the traditional social service nonprofits used the hundreds of thousands of volunteers who flocked to the area—into creating a nonprofit alternative to the public sector rather than a social movement to challenge the post-Katrina revanchist agenda.65

These supposedly activist NGO groups collectively received millions of dollars in funding from foundations such as Rockefeller, Ford, and Open Society (Soros) and local ones such as the Greater New Orleans Foundation (GNOF). The GNOF, in addition to doling out its own funds, also operated as what sociologist Darwin Bond-Graham calls a “capture foundation” by acting as a distributer of funds from larger foundations, such as the Gates Foundation and the Bush–Clinton Katrina Fund, to local groups. For example, one GNOF-managed fund was the Community Revitalization Fund (CRF), a $25 million endowment provided by ten major foundations, including Rockefeller and Gates, and other fervent supporters of privatization. Cathy Shea, a program officer at the Rockefeller Foundation and a “key coordinator in the creation of the fund,” made it clear that the CRF initiative was to fund replacement housing for “failed” public housing.66

The local activist nonprofits not only received funding from foundations but in some cases became incorporated into the governing structures of their financial backers. For example, after Katrina the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors created the Gulf Coast Fund for Community Renewal and Ecological Health, dedicated to supporting “local organizing” focused on “social justice concerns and movement building.” The Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors—an arm of the same Rockefeller Foundation that supported the demolition of public housing—sat many local activists, including Shana Griffin of INCITE!, Steve Bradberry of ACORN, Monique Harden of AEHR, and Angela Winfrey of the People’s Institute, on the fund’s advisory board. The major concern of many activist nonprofits in post-Katrina New Orleans was not that they were becoming incorporated into the nonprofit foundation complex. Rather, as expressed in an open letter signed by representatives of various local nonprofits, they were dismayed that foundations and other nonprofits had not delivered enough financial support to the local nonprofits on the ground in New Orleans. This level of criticism is typical, argues Joan Roelofs, of nonprofit leaders “who do not object to the hegemonic role of foundations”—that is, to the way they use their financial power to channel and contain movements. Rather, “they complain that large ‘progressive’ foundations are not giving enough.”67

Organized labor, operating in the form of a social movement unionism that links labor with community struggles, could have served as a political and financial counterweight to the influence of the foundations, yet U.S. labor unions, both locally and nationally, were not prepared to lead a larger fight against the post-Katrina disaster capitalism agenda. In fact, as mentioned, the major initiative of the AFL-CIO was through its banking arm, underscoring the extent to which financialization of the economy has penetrated even ostensibly working-class organizations. Instead of leading a fight against privatization, the union’s bankers were prepared to sacrifice public housing for a profitable investment deal. The local American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and their national affiliates did fight to regain collective bargaining rights that had been abrogated by state and local officials. Nonetheless, the AFT was neither willing nor prepared to lead a larger fight to defend the public sector, one that could have incorporated the struggle to defend public housing, health care, and myriad other issues facing black and working-class Katrina survivors.

C3 activists, for their part, criticized foundation funding, but at the same time, the group was incurring costs for transporting displaced residents and volunteers and was overstretched. On behalf of the organization, I reached out, unsuccessfully, for funds from two unions with a social movement unionism tradition—the local chapters of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) in Charleston, South Carolina, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) in San Francisco. C3 did obtain small donations from the local bricklayers’ unions and a Unitarian church in Ithaca, New York. Then, just after the PHRF refused to pay for the vans rented for the April protest, I was invited by the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (UUSC), who had established a fund to support social justice initiatives in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, to apply for a grant. C3 researched the UUSC and concluded that it shared more similarities with what Joan Roelofs has called radical “social change foundations” than with liberal foundations, such as Ford and Rockefeller, that were bankrolling most of the nonprofits.68 The group therefore voted to apply for a $20,000 grant to pay for transportation and other costs, as well as a modest stipend for an organizer, but made it clear that we would return the money if the UUSC undermined our independence. C3 received, in total, $40,000 from the UUSC that allowed me and, then, Elizabeth Cook to work as paid organizers for about year. The funds, which were handled by a church-based nonprofit, were exhausted by May 2007.

In the Streets and Courts

Despite failing to reoccupy St. Bernard during the summer of 2006, the public housing movement continued to mobilize. In mid-June 2006, for example, Survivors Village and C3 organized a march to Audubon Place—a wealthy gated community on exclusive St. Charles Avenue, located next to Tulane University. The marchers’ lead banner read “Make this Neighborhood Mixed-Income,” in reference to the justifications used to demolish public housing neighborhoods but, of course, never invoked to make uniformly wealthy ones more diverse. As St. Bernard resident Pam Mahogany quipped at the time, “We could mix in their community, [but] are they sure that’s what they want?” In late June and again on July 1, activists marched from the Iberville development through the French Quarter, as a warning that we were willing to disrupt the tourist industry if public housing residents were not allowed to return home.69

The public housing movement also began pursuing a legal strategy to block demolition. New Orleans–based human rights attorney Bill Quigley and Tracie Washington, along with lawyers from a large Washington, DC–based nonprofit, foundation-backed advocacy law firm—the Advancement Project—filed a class action in June 2006 against HUD to stop the demolitions (Anderson et al. v. Jackson). While welcoming the intervention, some activists raised concerns that the suit would lead the movement to look to the courts and professionals, rather than our own self-activity, as the key motor of change. The allure of the courts is particularly strong, civil rights advocate and litigator Michelle Alexander argues, in racial justice struggles “where a mythology has sprung up regarding the centrality of litigation,” particularly in flawed interpretations of the civil rights movements.70 To address these threats, activists such as Mike Howells emphasized in meetings that judges were simply “politicians in robes,” and others criticized efforts by some of the lawyers to drive a wedge between the plaintiffs—the residents—and the activists who did not live in public housing.71 Nonetheless, despite these damage control efforts, the suit did lead some residents to step back from protest and may have contributed to the failure to reoccupy the St. Bernard in June and July, as previously announced.

By the summer of 2006, with Iberville and a section of B. W. Cooper having been reopened as a result of protests, increasing numbers of public housing residents began returning to New Orleans. Although the Laffite, C. J. Peete, and St. Bernard developments remained closed, some of their displaced residents were able to use Section 8 vouchers to locate an apartment in New Orleans. Among returning public housing residents, a core group emerged, including the late Patricia “Sista Sista” Thomas and D. J. Christy from Lafitte; Gloria Irving, Sharon Jasper, her daughter Kawana, and Stephanie Mingo from St. Bernard; Sam Jackson from B. W. Cooper; sisters Bobbie and Gloria Jennings and Rosemary Johnson and Diane Allen from C. J. Peete; and Cody Marshall (after completing his offshore employment) from Iberville. This group played a leading role in the public housing and right of return movement.

For the first-year anniversary of Katrina, the public housing movement used the renewed spotlight on the city to highlight the government’s failure to reopen viable public housing while thousands of New Orleanians continued to be displaced. The contradiction was maybe most transparent at Lafitte, a well-crafted, little-damaged development situated, like Iberville, close to the French Quarter. To help draw attention to the issue, Soleil Rodrigue, the Common Ground liaison to the public housing movement, organized a spoof press conference with the Yes Men, a self-styled “culture-jamming” media activist team, and displaced Lafitte tenant Patricia Thomas. Posing as a HUD assistant secretary, the Yes Men and Thomas staged a ribbon-cutting ceremony at Lafitte where they announced that the agency had reversed its policy and was reopening all of the little-damaged public housing developments. Simultaneously, but not coordinated with the Yes Men event, C3 activists and several volunteers associated with Common Ground aided a displaced Lafitte resident in removing the metal doors that sealed off his apartment and reoccupying his home. The action led to several of the activists, but not resident D. J. Christy, being arrested by the New Orleans police for trespassing. The Loyola University legal clinic, run by activist attorney Bill Quigley, took this case and those of the scores of other activists arrested during the 2005–2008 fight to defend public housing. With the support of the People’s Organizing Committee, several C. J. Peete residents did later reoccupy their apartments in February 2007, but were persuaded to end their occupation under threat of arrest.72