Cognitive scientists have found out quite a lot about the psychology of intention. We humans are intentional to our core. Do we come into the world trailing clouds of glory? Maybe. But we definitely come trailing clouds of concepts. Far from experiencing the world as “one great blooming, buzzing confusion,” babies start detecting patterns only a few hours after birth. They segment, they process, they subdivide. They prefer their native language to a foreign tongue. They know about object solidity and object permanence. And by the age of roughly a year old, they have a fully developed Cartesian worldview, seeing objects and agents as distinct.

Why should this matter to literary theorists? (Is the baby father to the man?) After all, by the time they go to graduate school, babies have long since become immune to the brute lure of intentionality. They have laid down complex pathways on their innate concepts. They reason counterfactually, wreath their ideas in the flowers of prosody, willingly suspend their disbelief, and wrinkle their brows in ironic suspicion. And by the time they are middle aged and have come to appreciate that the world is, in fact, a great blooming, buzzing confusion, their infant categories are…

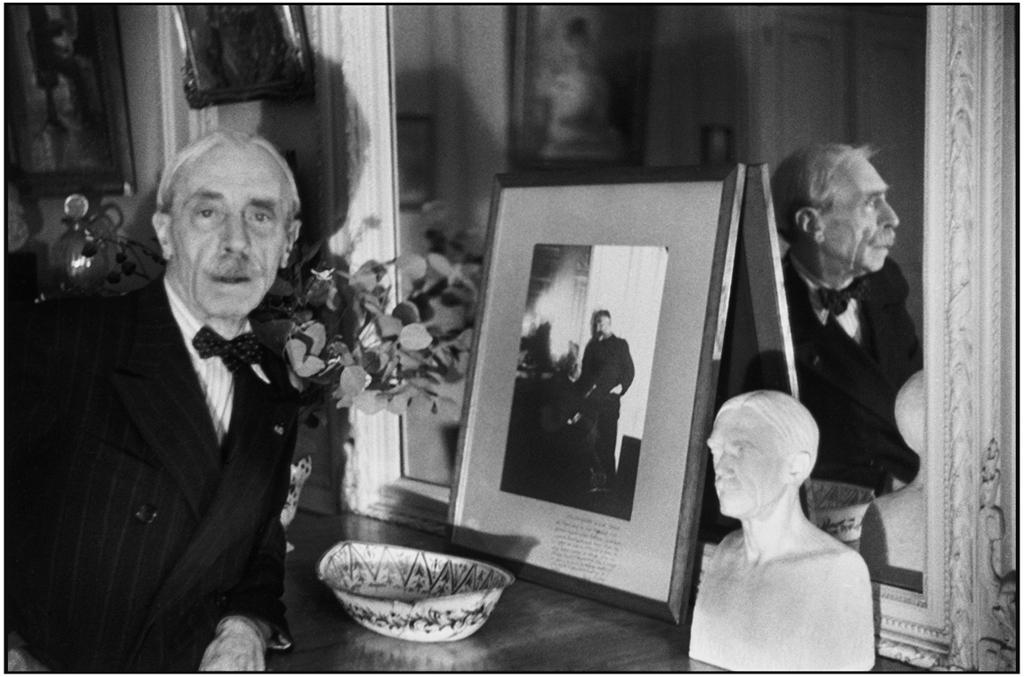

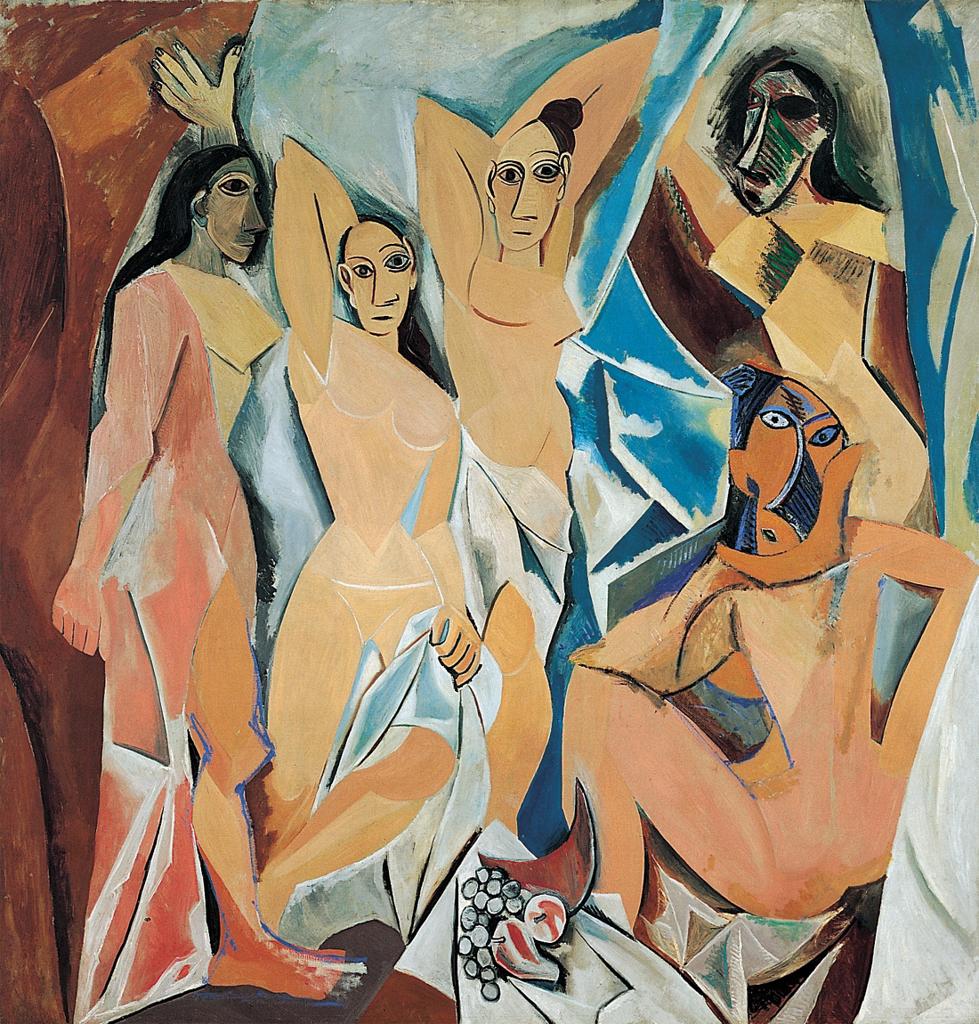

On this question Einstein and Kahnweiler held diametrically opposed positions. Moreover–and this is my main interest–their respective positions correspond to successive phases in the developing neuroscientific understanding of the visual brain. Kahnweiler’s interpretation of cubism was shaped by the neuroscience of his day while, remarkably, Einstein’s account of seeing, as he believed it to be embodied in cubist paintings, anticipates by half a century a fundamental breakthrough in the neuroscientific understanding of vision.

An excerpt from the Los Angeles Review of Books Symposium on “What is African American Literature?”

BY Brian Kane

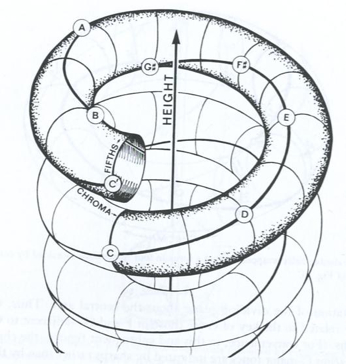

…I could agree with Mark Johnson, if his claim were simply descriptive in character. That is, I would find nothing objectionable if he were only claiming that we require multiple, often inconsistent structures (or habits, or preferences, or norms) to describe musical works. But Johnson’s claim is not intended to be descriptive; image-schematic theory is intended to explain how such experiences are conceptualized in the first place, i.e. how they are structured.

James Welling and Walter Benn Michaels discuss photography, neoliberalism and aesthetics in a conversation from a recent conference at Parsons, entitled The Photographic Universe and we’ve got the video.

…for me much of what is most immediately gripping in June 8, 1968 turns on the contrast or say the felt difference between the stagedness plus residual “magic” of absorption of the “mourners” and the wholly unselfconscious albeit dramatic, in certain scenes one might say over-the-top beauty of the natural world…

The political meaning of the refusal of form (the political meaning of the critique of the work’s “coherence”) is the indifference to those social structures that, not produced by how we see, cannot be overcome by seeing differently. It’s this refusal of form…

BY Todd Cronan

Poet and critic Paul Valéry held two strong and conflicting views of literary meaning. On the one hand, he affirmed his “verses have whatever meaning is given them.” And in a phrase that entered into the post-modern literary canon, he declared “Once a work is published its author’s interpretation of it has no more validity than anyone else’s.” On the other hand, he suggested that “One is led to a form by a desire to leave the smallest possible share to the reader.” Valéry’s career can be divided along these lines of anti-intentionality and intentionality. My larger claim is to show the primacy, or perhaps the invention of a dominant mode of twentieth- and twenty-first century thought.

W.G. Sebald’s long poem Nach der Natur (1988) contributed significantly to the swift recognition of his literary talent among fellow writers and poets, yet it received scant attention by the larger public and literary scholars alike.1 To the English-speaking world it was not even available until 2002, a year after its author’s death, when it appeared in Michael Hamburger’s excellent translation under the title After Nature. Like a triptych, it is divided into three untitled parts, each with a distinct thematic concern involving a specific historical period and a writer or artist: the first focuses on the Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald, the second on the eighteenth-century naturalist, travel writer, and Arctic explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller, and the last on elements from Sebald’s own biography.2 As opposed to Sebald’s later practice, apart from the landscape photographs that are reproduced on the end sheets of the first edition of Nach der Natur, there are no visuals in the volume, although paintings play a prominent role, especially in the first and final sections of the poem. In what follows, I shall support my reading of Sebald’s poem with reproductions of Grünewald’s paintings. I do so, however, in an attempt to provide…

BY Éric Michaud

We should give ourselves up to the lies of art to deliver ourselves from the lies of myth: it is by this very paradoxical and singular way of absorption into the framework of one of the “great works” of the Occident that Picasso belongs to myth. For if it is true that he always sought to combat myth, making him even more dependent on it, he only succeeded by turning myth’s own arms onto itself—that is, the “lie.”