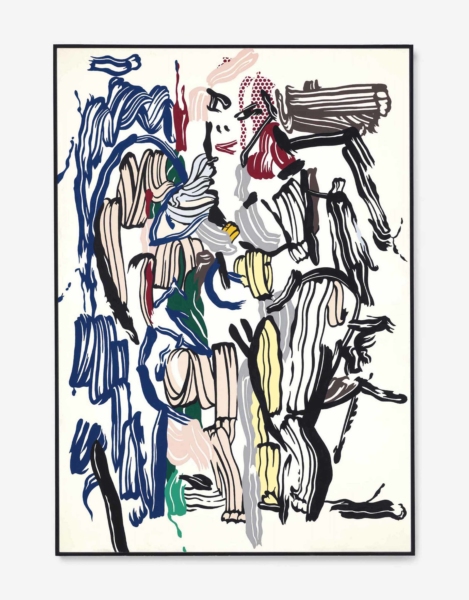

Introduction: Contemporary Art and the PMC (Parts One and Two)

PMC art rewards a viewer who does not enjoy emotional exchanges, but who does have strong, positive, hopeful feelings every time they figure out how a system works. Contemporary art has helped the PMC feel good about their choices and justified in their limits, in part, because an overriding emphasis on abstraction and system validates the type of solutions that our most lucrative skills tend to generate.