The right speaks deceitfully, but to people, the left quite truly, but only of things.

–Paraphrase of Ernst Bloch, 1935

We recognize it when we see it: someone is PMC when they turn to language or rules or theories or style or attitude or affect or critique or (more broadly) culture to measure what they stand for or what they stand against. Compare this to the right for whom cultural coherence, even logical coherence, is the enemy and the uncultured unreason of money and force sovereign. Or compare it to the left for whom what matters as measure is the political organization of workers. As Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich put it in a 2013 update to their foundational 1977 thesis, the PMC are the “‘rationalizers’ of society,” even if that role long ago lost most of its original white-collar professional status and is now increasingly left to a diminishing segment of “the ‘creative’ professions” that has some of the same freedom from debt that had momentarily—during the two plus decades of economic boom following World War II—allowed it “to take on a critical, even oppositional, political role.”1

As they explained at some length in 1979 to a phalanx of new left critics, the question of the PMC did not arise from the “specialized terms and ‘methods’,” “abstract theory” and “abstract grid” of “academic Marxology”—the field of battle these critics had engaged them on, they said—but instead had arisen specifically from a class analysis about that specialization, abstraction and academicization.2 The category of the PMC, in other words, was first and foremost “a problem facing the U.S. left,” they said, and was similar in kind to the earlier “shock of the left’s encounters with racism, and then sexism as internal problems on the left” (R 321, 315). The question that had set off their critics in summation was this: “Why was the left, especially the white left which emerged from the 60s, so overwhelmingly middle class in composition—to the point where the theoretical standard bearers of socialism, the working class, had become a problem for ‘outreach’” (R 317)? What had been since the 1930s largely a labor-centered working-class left, they answered, had been gentrified in the 1960s by a type of social actor first developed during the Progressive Era.

In 1977, they called this the “rebirth of PMC radicalism in the sixties” even if the later iteration was different in kind.3 Where the progressives had used “the device of professionalism” to extract themselves from subservience to the profit motive of their employers, 1960s radicals came increasingly to pit the struggle between lifeworld (or “culture” in its newly generalized anthropological sense) and system (or the form of structural violence developed by the alliance between political and economic elites that is the hallmark of the bourgeoisie).4 Culture, in other words, was the new technocracy and new meritocracy and thus the idiom for a new professionalism and a new managerialism. Theoretically and strategically this was expressed by a defining turn to an ever more intricate cosmopolitan cultural literacy and value system that was neither bourgeois nor proletarian for the basis of new left critique. Equally so, it involved a corresponding turn away from old left economic and political systems and actors like workers and politicians, unions and parties. In the end, the central contradiction of the new “PMC class consciousness, with its ambiguous mixture of [cultural] elitism and anti-capitalist militance” meant that the question of actually existing institutional power that might be used to materially improve one’s life and that of others fell by the wayside (NL 7, 10).

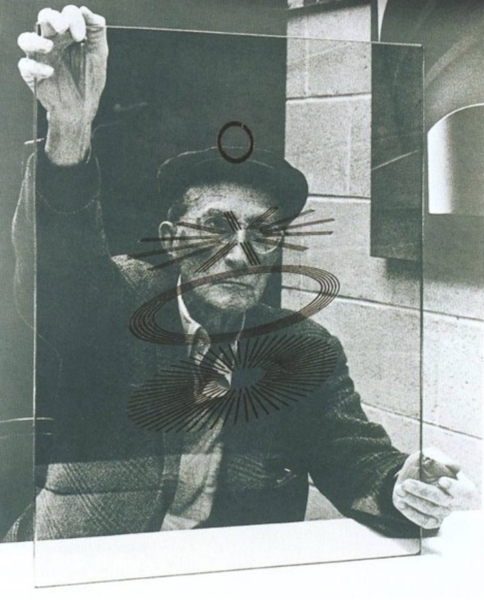

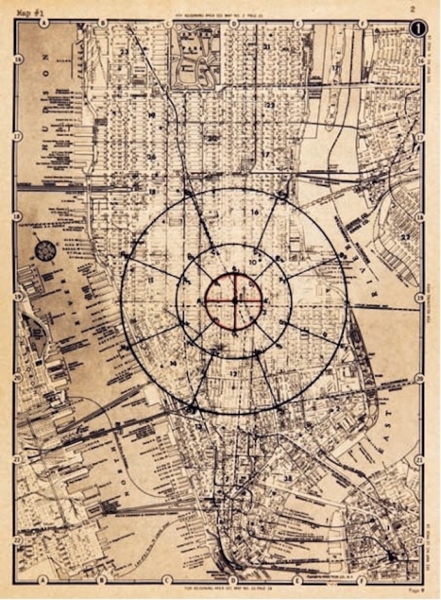

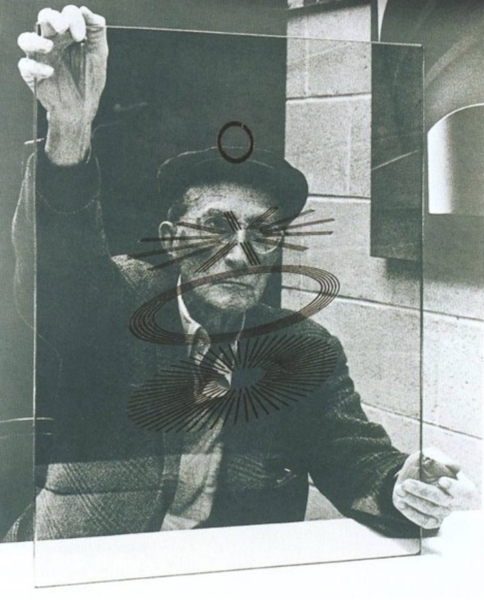

In short, someone is PMC insofar as her role as social theorist or critic is fetishistically split off and isolated from her agency as an economic or political actor. If we were to point to an artistic type that stands for the gradual development of this role over the course of the early and middle decades of the twentieth century we might look to the earlier artist-as-worker and its up-ticket correlate, the artist-as-engineer as it is transmogrified into the later twin figures of the artist-as-consumer and artist-as-student with their shared up-ticket correlate, the artist-as-cultural-critic. Art historians who look closely at my leading illustrations will see that development in spades (figs. 1 & 2). The Ehrenreichs’ 2013 illustration for the increasing social isolation and political powerlessness of this later incarnation was the “iconic figure of the Occupy Wall Street movement: the college graduate with tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debts and a job paying about $10 a hour” (DYD 10). For our purposes, we can imagine that debt having been incurred to pay for an art degree (as, in fact, it was for many).

***

Lenin famously drew out a related distinction in his 1920 pamphlet “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder. Beyond the historical variations, what we now broadly call the professional managerial class—or you choose from political historian Lily Geismer’s collection of related period tags: “professional middle class,” “knowledge class,” “educated class,” “knowledge worker,” “creative class,” “liberal elite,” “latte liberal,” “bobo,” “neoliberal,” or “Atari Democrats”5—Lenin in his day distinguished as the middle of three capitalist-era classes: “the liberal-bourgeois, the petty-bourgeois-democratic (concealed behind ‘social-democratic’ and ‘social-revolutionary’ labels), and the proletarian-revolutionary.” Leaning on scare quotes to call its political posturing into question, he flagged this progressive middle stratum as “‘left’” or “‘left-wing’” and, as his title tells us, diagnosed it with “infantile disorder.”6

Despite the various political labels used by Lenin and those he was criticizing (“‘left-wing’,” “communist,” “democratic,” “‘social-democratic’,” “‘social-revolutionary’,” etc.), the position of this middle stratum as he defined it was not determined by any coherent or consistent economic or political position but instead, like its new left heir in our time, was marked by its role providing cultural and social critique that obscured and thus crippled clear and effective economic and political thinking and organizing. Because the theories and critiques generated by this class would not matter in any constructive sense, they could, in the end, be any theory or critique at all. Thus they could not help but be obscurantist and diversionary and destructive, he argued, because they were not rooted in or serving any accompanying viable political organization. Regardless of how centrist/social-democratic, “‘left’”/anarchist, or whatever, such positions amounted to moral postures more than political programs. “A petty bourgeois driven to frenzy by the horrors of capitalism is a social phenomenon,” Lenin allowed, but the “instability of such revolutionism, its barrenness, and its tendency to turn rapidly into submission, apathy, phantasms, and even a frenzied infatuation with one bourgeois fad or another” had long proven itself to be inevitable (LWC 32).7

Socially and economically, in other words, this early iteration of the PMC was not defined primarily by this or that political stance or even by its economic relation to the “millions upon millions of petty proprietors,” Lenin explained, but instead by its cultural function: “They surround the proletariat on every side with a petty-bourgeois atmosphere, which permeates and corrupts the proletariat, and constantly causes among the proletariat relapses into petty-bourgeois spinelessness, disunity, individualism, and alternating moods of exaltation and dejection” (LWC 44). Because the “‘left-wing’” theories and moods were not grounded politically, more often than not such proletarian relapses were and continue to be a matter of reaction rather than influence. As the Ehrenreichs would put it in 1977, for example, “working-class anti-communism is not created by right-wing demagoguery (or bad leadership, or ignorance, though all these help); it grows out of the objective antagonism between the working class and the PMC” (NL 20).

The Ehrenreichs were focused on Mao-quoting, liberal-denouncing, socially inconsiderate professors and other such elements from the new left of the 1960s and 70s that had the effect of alienating workers, but the same was true of the “‘left’” communists that Lenin targeted.8 Indeed, the Eherenreichs added, and we might guess that Lenin would concur, working-class anti-leftism often “comes mixed with a wholesale rejection of any thing or thought associated with the PMC—liberalism, intellectualism, etc.” (NL 20). Sound familiar? The PMC, thus, is a class not defined by its role in production, like the proletariat, or its role in exploitation, like the bourgeoisie, but instead, as the Ehrenreichs’ original 1977 definition had it, by its role reproducing the cultural or ideological conditions necessary to maintain the relations of production and exploitation between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie (PMC 13). In short, the PMC are the unwitting ideologists of a bourgeoisie that has liberated itself from the dirty work of manufacturing consent.

A couple of months after his “Infantile” essay Lenin would describe the corrupting, culturalizing influence of the “petty-bourgeois-democratic” or “‘left-wing’” progressives this way:

The workers of all lands are ridiculing the wiseacres, not a few of whom call themselves socialists and argue in a learned or almost learned manner about the Soviet ‘system,’ as the German systematists are fond of calling it, or the Soviet ‘idea’ as the British Guild Socialists call it. Not infrequently, these arguments about the Soviet ‘system’ or ‘idea’ becloud the workers’ eyes and their minds. However, the workers are brushing this pedantic rubbish aside and are taking up the weapon provided by the Soviets.9

The gist is that what we now call the PMC (but perhaps, following Lenin, should instead call the “‘wiseacre’ class”) posits itself as reasonable or democratic or liberal or progressive or socialist or communist or anarchist or revolutionist or whatever—it doesn’t matter—but only ever does so scholastically or pedantically. Think of the defensively technocratic Marxologist or TED-talker, the fetishistically critical hermeneuticist of suspicion, the dissembling neoliberal ecosystem or actor-network theorist, or the symptomatically other-oriented, archly “creative” street protester as types in point.

The long-brewing turn from the residual state-centered critical philosophy of Kant and Hegel’s day that still grounded Lenin’s strategies and policies to the alternating anti-statist and technocratic, critical and traditional theory that has come to take its place since Lenin’s time has taken on a new culturally specific role more recently. As Hal Foster put it in 1996, for example, “critical theory has served as a secret continuation of the avant-garde by other means: after the climax of the 1968 revolts, it also occupied the position of cultural politics, at least to the extent that radical rhetoric compensated a little for lost activism.”10 From the get go, social contradiction has been the defining feature of this critical-theoretical continuation of the avant-garde or PMC continuation of “petty-bourgeois-democratic,” “‘left-wing’” or “wiseacre” progressivism. Laying bare its class structure by collapsing the old distinction between high culture and the avant-garde, Foster called this contradiction its “double secret service.” As “a high-art surrogate and an avant-garde substitute,” he noted, it “has attracted many different followers” (RR xiv). Those followers have ranged from the bohemian to the brahmin, with a lot of intrepid capitalists and spirited anti-capitalists among the broader spectrum of art enthusiasts in between. Few of these enthusiasts have understood themselves to be—or act on behalf of—workers as a class. As such, almost none have been agents of substantive democratization.

Lenin’s main point was not that “‘left-wing’” communists were anti-vanguardist or anti-party or anti-“Leninist” in the usual ways we understand such positions, or even that they were anti-worker per se.11 Instead, he judged them harshly for being generally anti-institutional and particularly for being anti-parliamentarian, anti-trade-union, and anti-Soviet (or what at the time he called “non-Party workers’ and peasants’ conferences”). Such institutions, Lenin insisted, were not “systems” or “ideas” conjured out of thin air by activists but instead were living “human material bequeathed to us by capitalism.” As such, they were tools available for social change. Anything else—“abstract human material,” for example, or “human material specially prepared by us”—was not, he said, “serious enough to warrant discussion” (LWC 50). Only actually-existing networks of power produced by and for the capitalist relations of production were a realistic basis upon which one can fight for a better world, he argued—anything else is delusional or “infantile” because it is powerless. Lenin’s charge to his moralizing, more-despairing, more-left-than-thou comrades—predecessors of our alternately more-sardonic-than-thou and more-woke-than-thou PMC colleagues today—was, effectively, this: Grow up and address the world as it is, not from the standpoint of what you would wish it to be. Enough with your “systems” and “ideas,” your “theories” and “critiques,” your airy dream that “another world is possible.” It is time to get to work with the actually-existing tools at hand. In his own words, he called them “a group of intellectualists and of a few workers who ape the worst features of intellectualism” (LWC 57). Ouch.

***

Lenin was not alone in this appraisal. Think, for example, of Marx railing against the period intellectualism of his day, “the pompous catalogue of the ‘inalienable rights of man’,” insisting instead that “labourers must put their heads together, and as a class, compel the passing of a law,” and explaining that this “can only be effected by converting social reason into social force, and, under given circumstances, there exists no other method of doing so, than through general laws, enforced by the power of the state.”12 Indeed, we might speak of three key phases or versions of Lenin’s mandate to grow up and take on the world as it is: Marx’s foundational challenge to romantic anti-capitalism (think, for example, of the polemic in his “Critique of Critical Critique,” as he and Engels subtitled their 1844 screed The Holy Family), Lenin’s intermediate update to that challenge calling out the romantic anti-statism and anti-institutionalism more generally, and a third position that attempted to update Marx and Lenin that has a particular relevance for us today: Ernst Bloch’s challenge to romantic anti-communitarianism.13

Bloch encapsulated the problem as he saw it in 1935 with his well-known pithy summary statement “Nazis speak deceitfully, but to people, the Communists quite truly, but only of things” (HOT 138). The left’s theories and critiques may well be true but insofar as they are merely “systems” and “ideas” and not forms of direct engagement with and transformation of the existing forms of sociality and thus relations of power at hand, they speak in the PMC manner “only of things,” of cultural relations devoid of any coherent account of the desires vested in them or how to act on those desires. As such, they are vulgar, simplistic, reductive and naive. “In this way,” Bloch wrote about Brechtian montage but generally addressing the black-box systems theory of his day, “adventurous and distant romanticism move[s] into a cooled and experimental object; the distant scene of the action turns into a future one, anarchy (the best part of every exoticism) turns into a kind of laboratory, an open experimental space” (HOT 226). The romantic fullness of anti-systemic myth becomes the romantic emptiness of anti-intentional system. “It is a precisely upper middle-class void,” Bloch insisted, because “every thrust or idea from below is lacking” (HOT 217).

In a word, such a romantic anti-communitarianism is infantile. It does not address the world as it is because it does not address people as they are and instead rests in what Lenin called “abstract human material,” or the delusion of “human material specially prepared by us” or human nature presumed to be remade by lordly fiat as if it were an artwork or design problem for “engineers of the human soul.”14 It is managerial-speak, system-speak, theory-speak, critique-speak, art-speak that sophomorically and romantically presents itself as “the other side of ‘empty mechanics’,” Bloch said, and as such it is “under a curse of virtually confirming the hatred of reason among those who are proletarianized (as if all reason resembled the halved capitalist kind of today)” (HOT 139). In so doing, such an intellectualist leftism could never hope to win the support necessary to take power and instead could at best only dream of endlessly, tirelessly chattering on in the name of “critique” or “theory” together with that chatter’s painfully innocent twin, the ever-retreating “other world” that is said to be “possible.”15

So, how to speak at once “quite truly” and equally “to people”?

Bloch defined the parameters of such a project negatively: “since Marxist propaganda lacks any opposite land to myth, any transformation of mythical beginnings into real ones, of Dionysian dreams into revolutionary ones, an element of guilt also becomes apparent in the effect of National Socialism, namely a guilt on the part of the all too usual vulgar Marxism” (HOT 60). Oskar Negt would later summarize Bloch’s position about such mythical beginnings, Dionysian dreams and other such communitarian impulses this way: “either they will be appropriated by socialism or they will be added to the resources of its enemies—there is no third possibility.”16

From our perspective now, a similar “guilt on the part of the all too usual vulgar Marxism” can be fairly attributed to the likes of us for the successes of Putinism, Trumpism, Erdoganism and their ilk. Without question, conjuring our own innocence and “hoarding” it, as Catherine Liu would put it, is the single most infantile, romantic, PMC and predictable response to the world we find ourselves in today that we could have.17 Certainly it is true that in our day, as in Bloch’s era of rising fascism, we have produced no viable “opposite land” to myth, no effective means for transforming mythical impulses into real ones. As the “‘rationalizers’ of society” there is not a whole lot of good we can do, but even there—in the rationalizing that is our reason for being—we have failed.

***

This failure has been usefully surveyed and summarized by a number of observers. Thomas Frank, for example, writes with scorn of the “thick patina of expert-talk” which, he says, we stalwart loyalists of the PMC find “irresistibly beguiling” and serves to divert attention and desire away from any meaningful left political program.18 The sociologist Cihan Tugal provides an account that deserves quoting at length because it speaks pointedly to the diluted Dionysianism that we have produced in lieu of its socialist alternative:

The ghosts of incomplete revolutions, all the way from 1848 to 1979, are haunting the globe. A particular genie, the unpredictable middle strata, will continue to upset many hopes in the coming years. Sanguine and unidirectional investments in the ‘new middle classes’ have upheld these strata as the true bearers of democracy, post-materialism, the free market, and tolerance. Such false hopes peaked in the 1980s, but they still cloud minds. … Heavy new petty bourgeois participation in and leadership of the post-2009 revolts reinforced (but did not singlehandedly create) the disorganized (not really ‘leaderless’) and unfocused tendencies of post-1979 revolt. Entertainment, carnivalesque aesthetics, and politics were linked innovatively … [but the] aestheticized atmosphere of the revolt (with its unavoidable class character) turned out to be a double-edged sword—one edge facing the dominant order and the other the popular strata. … The most salient disposition of this class is neither simply tolerance (as in mainstream accounts) nor horizontalism (as in the current radical accounts). The key new petty bourgeois tendency is rather the monopolization of skill and the concomitant ‘ideology of the ladder’, contradictorily married to democratic and collectivist ideologies. The aestheticization of politics is among the core tendencies of this class … [which makes it averse] to organization and collective discipline … [and thus] devoid of the capacity to offer programmatic ways out of the crisis of capitalism.19

Needless to say, the foremost skillset monopolized by this middle stratum and made into an ever-shifting ladder that in equal parts intimidates and is resented by those who fall below the educational threshold of the PMC is the range of cultural competencies or the “thick patina of expert-talk” that grease the wheels of capitalist globalization. For our purposes, one particularly sharp area of cultural competency or domain of expert-talk is contemporary art, particularly insofar as it has merged with our current leading “creative” or carnivalesque brand of activism and its romantic anti-capitalism, anti-statism and anti-communitarianism.

Indeed, we might take the direction of the contemporary art that has dominated the global market since World War II to be our cutting-edge cultural expression of the bad faith postmodernist position identified by Wendy Brown:

So we have ceased to believe in many of the constitutive premises undergirding modern personhood, statehood, and constitutions, yet we continue to operate politically as if these premises still held, and as if the political-cultural narratives based on them were intact. Our attachment to these fundamental modernist precepts—progress, right, sovereignty, free will, moral truth, reason—would seem to resemble the epistemological structure of the fetish as Freud described it: “I know, but still…” What happens when the beliefs that bind a political order become fetishes?20

Brown raised this question in 2001 and, needless to say, after the rise of Putinism, Trumpism, Erdoganism and all the rest we now know the answer. Without a sustainable and compelling counternarrative to ethnonationalism, without a vision of, and feeling for, the modern freedoms created and enforced by the democratic state, without a lived investment in and fidelity to the political mechanisms that check the incessant market-amplified urge to consolidate wealth and power by any means possible, the radical upwards redistribution of wealth and political power and its instrumentalization of popular resentment now seems inevitable.

So, what is to be done?

The great realist and dialectical—or more simply, as Lenin implies, adult-like—choice made by Marx, Lenin and Bloch was to accept the conditions of power as they were in the worlds they inhabited rather than pining away for another world, or worse, conjuring new theories or systems or critiques, or worse still, falling back on the unalloyed purity of irony, cynicism, melancholy or despair. Marx looked to the heart of capitalism to find its gravediggers—hard at work in the newly organized sweatshops of factory production—just as Lenin looked to the heart of bourgeois democracy—parliamentarianism—and just as Bloch looked to the heart of Nazism with its vulgar and spite-filled myths of blood, soil and the like as the bonding agent for rising fascism.

Each of these were first and foremost objects of critique, of course, but more importantly they were also sites of power that, in theory, could be redirected away from alienation to enlightenment, from exploitation to freedom, and used as stepping stones to larger revolutionary aims. Arguably, Marx and his allies substantively if only partially succeeded in that redirection in their day just as Lenin and his allies did in theirs. In Bloch’s day, by comparison, the left failed to win the popular support needed to effectively counter the rise of fascism and capitalism both. As Tugal suggests, that failure continues to haunt us now.

***

So, what resources do we have in our actually existing world now that might be successfully repurposed toward the left goals of enlightenment, popular empowerment and socially-realized universal freedom? What are our equivalents to the factories which Marx came to see as unparalleled tools of class consciousness and Lenin’s parliaments which, as he put it, were “not only useful but indispensable to the party of the revolutionary proletariat” (LWC 61)?

Bloch said that what the left lacked in 1935 was a viable substitute for community-binding myth that could transform its alienated impulses into real ones. If the single greatest myth of Marx’s and Lenin’s long nineteenth century was the collapse of enlightenment reason into technocratic reason and political progress into technological progress, the single greatest myth of Bloch’s twentieth century, as with our twenty-first, is identity. Of course, our notion of identity is less bound to the national cultures of the early and middle twentieth century with their national languages, origin stories and aspirational dreams, and instead are more tied to the spatialized notion of community. Like nationalism, communitarianism is defined by social ties and therefore bloodlines but with more elastic, less-defined geographical restrictions and thus greater potential for more varied, experimental, dispersed and potentially fertile and far-reaching networks. In a word, our twenty-first-century identitarianism is defined by “glocalism.”

So what can be done with the sense of community we have, but understood as a potential political resource in the dialectical manner of Marx’s approach to the factory and Lenin’s to parliament?

Without question, Eric Hobsbawm was right in 1996 when he said that the concept of “community” as it developed over the course of the twentieth century into a pseudo-sacred ideal was “a new and dangerous element” that has had devastating consequences for any left political project. More and more after World War II, the principle of community has come to displace the role of political parties and trade unions as the leading formal principle actively organizing (or disorganizing) collective self-imagining. This is nowhere more visible than in the rise of left-liberal NGOs (although contemporary art may give them a run for their money) and nowhere more consequential than in the rise of the “Anti-Communist International” or clandestine network of paramilitary intelligence operatives and death squads that conduct hidden foreign policy by extra-statist means.21 “After a period of virtually unbroken advance from the late eighteenth century to the 1960s,” the state and its institutions have “entered an era of uncertainty, perhaps of retreat,” Hobsbawm concluded. “A phase of state development which lasted for about two centuries,” he warned, “is now at an end” and what we are left with is nothing more or less than “barbarism.”22 Where the nation had been an engine of state formation, the principle of community, he argued, has been the social-theoretical motor driving, or, better, enabling, its collapse further and further towards the nightwatchman state that neoliberals have long argued for and the neofeudal system of privatized governance that white supremacists, dark enlightenment enthusiasts, and other unapologetic advocates of birthright inequality pine for.

However, if our provisional analogy holds, community—like the factory for Marx and the parliament for Lenin—might best serve us as both a primary object of critique and at one and the same time that which most needs to be re-theorized and reactivated for left political ends. This observation by journalist Matthew Cunningham-Cook offers us an entry point into thinking through this question:

Union organizing campaigns often depend on reservoirs of working-class consciousness in the workers they seek to organize. But with unions now spread so thinly across the country, and almost completely absent from many states, particularly in the South, organizers often have to build on other forms of consciousness—community, racial, gender. That’s why the point of entry to organizing workers—whether in a union or, given all the obstacles to forming unions, in other kinds of groups—may depend more on establishing a good record for the group in the community.23

It is a simple, commonsensical point, and in fact one that has long been a key tool for organizers but nonetheless is routinely lost in the “thick patina of expert-talk” of the PMC, the language of a left that routinely loses its capacity for dialectical thought in the heady romanticism of theory and critique despite ample evidence to the contrary.24

The Ehrenreichs said the same thing: a “wholly vocational approach to class leaves out everything else which shapes a person’s political consciousness and loyalties—their experience of other classes, their family and friendship ties, their experiences as a consumer of services, their notion of their ‘community’” (R 325). That “shaping,” they insisted, is the only arena in which organizing might stand a chance. Myriad others have made the same point many times over the years even if they are not always heard, but I’ll cite just one further example. Labor organizer Jane McAlevey puts it this way: “organic ties to the broader community form the potential strategic wedge needed to leverage the kind of power American workers haven’t had for decades.”25 For example, if “faith matters to workers,” she explains, “it has to matter to unions” (NS 68).

The working assumption is that organizers and those seeking to be organized are much more likely to be successful if they organize people in their lives as they are rather than as they might wish them to be. By “systematically structuring their many strong connections—family, religious groups, sports teams, hunting clubs—into their campaigns,” McAlevey argues, organizers have much more actually-existing social power at their disposal than if they address them only as workers (NS 28). In the process, community is rescued from its alienated status as mere culture—that is, as a picturesque bearer of reified identity—when it enables the collective exercise of political will. Just as a worker-owned-and-operated factory holds out the promise of redeeming the factory form, or a constituent assembly bears the promise of redeeming the parliamentary form from, as Lenin had it, deciding “once every few years which members of the ruling class are to repress and crush the people,” so the systematically structured political organization of the community form bears the promise of redeeming a culturalized and thus balkanized identity-centered communitarianism.26

If we accept Brown’s premise that state and individual sovereignty alike “require fixed boundaries, clearly identifiable interests and identities, and power conceived as generated and directed from within the entity itself” and that in our day “none of these requirements is met easily” then it would be a fool’s errand to prematurely invest too much political capital in the old institutions of the citizen and state apparatus (PH 10). One can conjure all the images of revolutions and revolutionaries one likes without much reasonable hope of gaining sufficient popular support to change anything. How we came to this condition of emptied modern subjects and emptied modern institutions is another question and, anyway, doesn’t matter.27 Our doubt about the modernist narrative of progress and the social and psychological structures that once founded it is what it is.

***

With the future foreclosed, there has been a tendency to look to the past instead. As one historian has put it, “liberals today are more committed than ever to a passionate remembrance of things past,” but instead of looking backwards to bring usable political insight forward into present action, they “now travel in the opposite direction, from present injustice to historical crime.”28 Origin narratives can guide in the same way progress narratives do by setting a direction, of course, but they typically produce two codependent problems—an undue and undemocratic sense of entitlement and an overwrought and politically ineffective sense of grievance—both of which exacerbate identitarianism and thereby undermine the necessary conditions of possibility for political organization. For a long time now, in the wake of our lost access to futurity, this has been our default approach to self-understanding in the name of identity, ontology, bare life, affect and myriad other such futile reaches for the primordially real. But as Brown observed, these are our fetishes—they “make a cultural or political fetish out of subordinated identities, out of the effects of subordination”—and as such are little more than vestigial yearnings from the past serving ideological ends in the present (PH 26). They have none of the emergent force that factories and parliaments once did or that, in principle, community might have for us now.

So, if the factory and the parliament were both at once the scene of the crime and a requisite hammer of justice for Marx and Lenin—“not only useful but indispensable to the party of the revolutionary proletariat,” as Lenin had it—what is the specific work that community can do?

There is its role as a stepping stone to the class consciousness necessary for labor organizing in the manner outlined by Cunningham-Cook, and there is its role as a medium of available oppositional power outlined by McAlevey, but we might also point to a third, more ephemeral and more challenging but nonetheless foundational role. This too is very much part of the history of thought and practice but is also a tool that the left has largely relinquished to the right, and—again and again—with devastating consequences. Hegel called this third role “the domiciliation of the divinity”29 and described the work that it accomplishes this way:

But when the Kingdom of God has won a place in the world and is active in penetrating worldly aims and interests and therefore in transfiguring them, when father, mother, brother, meet in the community, then the worldly realm too for its part begins to claim and assert its right to validity. If this right be upheld, the emotion which at first is exclusively religious loses its negative attitude to human affairs as such; the spirit is spread abroad, is on the lookout for itself in its present world, and widens its actual mundane heart. The fundamental principle itself is not altered; inherently infinite subjectivity only turns to another sphere of the subject-matter. We may indicate this transition by saying that subjective individuality now becomes explicitly free as individuality independently of reconciliation with God.30

Human society can be organized in myriad ways but the historical record suggests that without the kind of consensus that Hegel describes it defaults less to Hobbes’s war of all against all and more to a mundane social Darwinism or everyday Nietzschean triumph of the externalization of instincts by the strong over and against their internalization by the weak. We might take Putinism, Trumpism, Erdoganism and their ilk as cases in point. The only safeguard, and thus the only route to human freedom, Hegel tells us, is the divination process that “widens its actual mundane heart” or the establishment of, and consent to, a first principle of justice as the cornerstone of the institutions that enable human flourishing.31 That first principle is ever-threatened and ever needs to be renewed through the process itself.

***

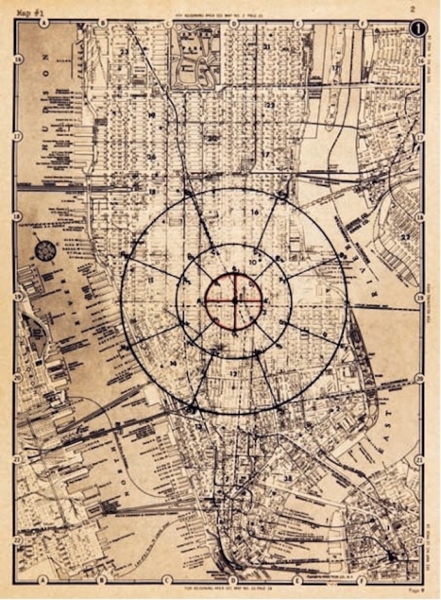

Any given artwork is built out of a broad spectrum of elementary components. There is the historical record of artistic and other languages it draws from, the specific economic and other material conditions that enable it, the mix of intentions of the artist, gallerist, patron, etc., the medium or mix of media, the arrangement of its different constituent parts, and there are the various social forms that authorize and validate it and that it authorizes, validates and redirects in turn. Regardless of whether it exercises skill and innovation or, more commonly for contemporary art, deskilling and critique, most art climbs what Tu?al called the “‘ideology of the ladder’ contradictorily married to democratic and collectivist ideologies.” Recent examples are easy to come by—think of Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Community of Fragments” as a case in point (fig. 3)—as a continuation of the systems-theory consensus consolidated in the 1960s (figs. 1 & 2) and addressed by Elise Archias in her introduction to this special issue. Since the 1960s the steps of that ladder have been mostly made up of the runes of cosmopolitanism, global consumerism and global tourism, of NGOs and anti-statism and anti-nationalism, of cultural critique and cultural tolerance and patronizing, particularizing, commodifying humanitarianism—that is, of a world that is structured, mediated and determined by the demographic needs of the market as the determinant medium of global sociality and false prophet of freedom. In the process it ever widens the gulf between PMC and the working class.

For those serious about any meaningful left ambition, the job of art or any other form of cultural intervention is nothing more or less than to shrink that gulf. Insofar as the Ehrenreichs’ foundational definition holds, that job will be difficult. As they put it in their original article, the “‘middle-class’ left” or PMC is, “to a very large extent, the left itself.” While it “may sense the impasse created by the narrowness of its class composition” largely devoid of the working-class participation or support it would need to achieve any of its political goals, they argued, it “lacks even the terms with which to describe the situation, much less a strategy for overcoming it” (PMC 7). Their point in the end was that this lack itself—manifest in the constant confusion of any meaningful class analysis by the proliferation of endless social and cultural distinctions each battling for its piddly market share—is the primary product of the PMC as a class. This is just another way of reiterating the primary take-home point they began with: that the PMC is defined as a class by being “nonproductive” and as such finds its social foothold by being “a class concerned with the reproduction of capitalist culture and class relationships” through its work of putting culture in the place of—rather than in aid of—labor organizing (PMC 15). Regardless of its feints to the left, in other words, the PMC cuts right insofar as, in the final analysis, its endless chatter means little more than the reproduction and enhancement of its own professional market share within a handful of culture industries. Practically speaking, the only place for its theories, critiques and outrage to go once they have moved on from the heady realms of TED talks, seminar rooms and street protests is to merge with right dissimulation in the diluvial draining away of the organized popular power that time and again has proven to be the only sustainable means to successfully democratize anything.

The opposite land to the PMC’s culturalization of political life is simple, particularly when we understand the work of culture as the Ehrenreichs do. That work is, as Cunningham-Cook, McAlevey and many others tell us, organization. Community—when wrested from the clutches of the culturalists—will continue to be a useful tool for organizers with or without us. Right communitarianism understood as the displacement of the political organization of labor by seeding the cultural self-recognition of communities defined by race, ethnicity, sexuality, etc., is, as Hobsbawm said, nothing more or less than barbarism. Left anti-communitarianism understood as the disavowal of the role such communities play in any realistic effort to take power is equally barbaric. Both are bad faith substitutes for modern freedom.

We know we are in the idealist purgatory of bad art when its justification is based on language or rules or theories or style or attitude or affect or critique or, more broadly, culture, regardless of whether it involves the promotion of communitarianism or its disavowal. By contrast, we know we are in the concrete utopia of good art when the category of art itself seems not only credible but desirable and approachable because it itself seems like a tool of organization. It has been a long time since we have been able to feel this set of feelings with any meaningful consistency—the feelings that once distinguished art from culture through organization—but we can remember what it was said to feel like if we look for it. It is not hard to find. Joshua Reynolds famously sketched the foundational distinction in 1771, for example, when he said, “A History Painter paints man in general; a Portrait Painter, a particular man, and consequently a defective model.”32 Reynolds was too schematic and so was not able to articulate how the general and particular work together but two decades later, Immanuel Kant would integrate them into a common experience when he spoke of “what pleases or displeases only through feeling and not through concepts, but yet with universal validity.”33

It is small beer, for sure, but, in the end, the kind of work we do reaching for an opposite land to the mythical particularism of nation or community or culture through the public exercise of the universalism of good taste succeeds by creating the conditions of possibility for seeing the forest for the trees. If we can convince a few readers or colleagues or students or artists or art aficionados to move away from the bad faith fetishism defined by Brown that has been the default post-enlightenment anti-ideal for the PMC for 60 or 70 years (and an ever-reliable resource for the divide-and-conquer tacticians on the right), and those that we convince in turn can convince a few more, then maybe we’ll find ourselves a little closer to the cultural preconditions that enable and extend the promise of organizing rather than threaten to undermine it. With this, maybe the terminology and strategy for producing solidarity that we are missing will more readily emerge and we will be better able to articulate once again what that opposite land to myth is.

The slogan “Workers of the world unite!” worked wonders in its day both in setting an agenda and in conjuring an opposite land to its prevailing period myths—techno-capitalist progress, national cultures, guildism, and all the rest—but it had the rising tools of factory production and the ruse of colonialism’s “civilizing mission” as its levers. Our leading prevailing myth, as dispiriting as it may be, is a renewed anti-democratic ethnonationalism and its rising tool is internet-fueled communitarianism. Like factories and parliaments and colonialism, the communities produced by the myriad strands of parastatist communitarianism are what they are. Merely complaining about this development accomplishes nothing. The left has a long history of giving up powerful tools for political organization to the right, or at least not battling wholeheartedly for them—religion, patriotism, and local politics not being the least of them. The question—and it is really the only question at this point for a PMC culture industry that seeks to do more than inadvertently rationalize the rule of our increasingly powerful and autocratic overlords—is how do we redirect and reclaim our rising communitarianism in order to redeem its soul.34 The organizing tactic that now goes by the name “Bargaining for the Common Good” or BCG may be one answer for organizers precisely because it seeks to link labor and community organizing and needs.35 For us, a critical model of art that turns to the affective bases of community and labor organizing—the shared urge for justice and self-determination—and uses those bases to organize itself may be something that we can do. My example of an artwork that might fit this bill is the 2018 community reenactment film Bisbee ‘17 directed by Robert Greene (figs. 4 & 5).

The basis for success that workers possess and we do not, Marx noted in 1864, is numbers, “but numbers weigh in the balance only if united by combination and led by knowledge.”36 Using our primary tools of aesthetic experience and aesthetic education, we artists, art critics, art historians and our fellow travelers can play a role supporting the work of organizers working to make community into a left organizing tool in the way that factories and parliaments once were, but only if we are willing to switch sides.

Notes

The right speaks deceitfully, but to people, the left quite truly, but only of things.

–Paraphrase of Ernst Bloch, 1935

We recognize it when we see it: someone is PMC when they turn to language or rules or theories or style or attitude or affect or critique or (more broadly) culture to measure what they stand for or what they stand against. Compare this to the right for whom cultural coherence, even logical coherence, is the enemy and the uncultured unreason of money and force sovereign. Or compare it to the left for whom what matters as measure is the political organization of workers. As Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich put it in a 2013 update to their foundational 1977 thesis, the PMC are the “‘rationalizers’ of society,” even if that role long ago lost most of its original white-collar professional status and is now increasingly left to a diminishing segment of “the ‘creative’ professions” that has some of the same freedom from debt that had momentarily—during the two plus decades of economic boom following World War II—allowed it “to take on a critical, even oppositional, political role.”1

As they explained at some length in 1979 to a phalanx of new left critics, the question of the PMC did not arise from the “specialized terms and ‘methods’,” “abstract theory” and “abstract grid” of “academic Marxology”—the field of battle these critics had engaged them on, they said—but instead had arisen specifically from a class analysis about that specialization, abstraction and academicization.2 The category of the PMC, in other words, was first and foremost “a problem facing the U.S. left,” they said, and was similar in kind to the earlier “shock of the left’s encounters with racism, and then sexism as internal problems on the left” (R 321, 315). The question that had set off their critics in summation was this: “Why was the left, especially the white left which emerged from the 60s, so overwhelmingly middle class in composition—to the point where the theoretical standard bearers of socialism, the working class, had become a problem for ‘outreach’” (R 317)? What had been since the 1930s largely a labor-centered working-class left, they answered, had been gentrified in the 1960s by a type of social actor first developed during the Progressive Era.

In 1977, they called this the “rebirth of PMC radicalism in the sixties” even if the later iteration was different in kind.3 Where the progressives had used “the device of professionalism” to extract themselves from subservience to the profit motive of their employers, 1960s radicals came increasingly to pit the struggle between lifeworld (or “culture” in its newly generalized anthropological sense) and system (or the form of structural violence developed by the alliance between political and economic elites that is the hallmark of the bourgeoisie).4 Culture, in other words, was the new technocracy and new meritocracy and thus the idiom for a new professionalism and a new managerialism. Theoretically and strategically this was expressed by a defining turn to an ever more intricate cosmopolitan cultural literacy and value system that was neither bourgeois nor proletarian for the basis of new left critique. Equally so, it involved a corresponding turn away from old left economic and political systems and actors like workers and politicians, unions and parties. In the end, the central contradiction of the new “PMC class consciousness, with its ambiguous mixture of [cultural] elitism and anti-capitalist militance” meant that the question of actually existing institutional power that might be used to materially improve one’s life and that of others fell by the wayside (NL 7, 10).

In short, someone is PMC insofar as her role as social theorist or critic is fetishistically split off and isolated from her agency as an economic or political actor. If we were to point to an artistic type that stands for the gradual development of this role over the course of the early and middle decades of the twentieth century we might look to the earlier artist-as-worker and its up-ticket correlate, the artist-as-engineer as it is transmogrified into the later twin figures of the artist-as-consumer and artist-as-student with their shared up-ticket correlate, the artist-as-cultural-critic. Art historians who look closely at my leading illustrations will see that development in spades (figs. 1 & 2). The Ehrenreichs’ 2013 illustration for the increasing social isolation and political powerlessness of this later incarnation was the “iconic figure of the Occupy Wall Street movement: the college graduate with tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debts and a job paying about $10 a hour” (DYD 10). For our purposes, we can imagine that debt having been incurred to pay for an art degree (as, in fact, it was for many).

***

Lenin famously drew out a related distinction in his 1920 pamphlet “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder. Beyond the historical variations, what we now broadly call the professional managerial class—or you choose from political historian Lily Geismer’s collection of related period tags: “professional middle class,” “knowledge class,” “educated class,” “knowledge worker,” “creative class,” “liberal elite,” “latte liberal,” “bobo,” “neoliberal,” or “Atari Democrats”5—Lenin in his day distinguished as the middle of three capitalist-era classes: “the liberal-bourgeois, the petty-bourgeois-democratic (concealed behind ‘social-democratic’ and ‘social-revolutionary’ labels), and the proletarian-revolutionary.” Leaning on scare quotes to call its political posturing into question, he flagged this progressive middle stratum as “‘left’” or “‘left-wing’” and, as his title tells us, diagnosed it with “infantile disorder.”6

Despite the various political labels used by Lenin and those he was criticizing (“‘left-wing’,” “communist,” “democratic,” “‘social-democratic’,” “‘social-revolutionary’,” etc.), the position of this middle stratum as he defined it was not determined by any coherent or consistent economic or political position but instead, like its new left heir in our time, was marked by its role providing cultural and social critique that obscured and thus crippled clear and effective economic and political thinking and organizing. Because the theories and critiques generated by this class would not matter in any constructive sense, they could, in the end, be any theory or critique at all. Thus they could not help but be obscurantist and diversionary and destructive, he argued, because they were not rooted in or serving any accompanying viable political organization. Regardless of how centrist/social-democratic, “‘left’”/anarchist, or whatever, such positions amounted to moral postures more than political programs. “A petty bourgeois driven to frenzy by the horrors of capitalism is a social phenomenon,” Lenin allowed, but the “instability of such revolutionism, its barrenness, and its tendency to turn rapidly into submission, apathy, phantasms, and even a frenzied infatuation with one bourgeois fad or another” had long proven itself to be inevitable (LWC 32).7

Socially and economically, in other words, this early iteration of the PMC was not defined primarily by this or that political stance or even by its economic relation to the “millions upon millions of petty proprietors,” Lenin explained, but instead by its cultural function: “They surround the proletariat on every side with a petty-bourgeois atmosphere, which permeates and corrupts the proletariat, and constantly causes among the proletariat relapses into petty-bourgeois spinelessness, disunity, individualism, and alternating moods of exaltation and dejection” (LWC 44). Because the “‘left-wing’” theories and moods were not grounded politically, more often than not such proletarian relapses were and continue to be a matter of reaction rather than influence. As the Ehrenreichs would put it in 1977, for example, “working-class anti-communism is not created by right-wing demagoguery (or bad leadership, or ignorance, though all these help); it grows out of the objective antagonism between the working class and the PMC” (NL 20).

The Ehrenreichs were focused on Mao-quoting, liberal-denouncing, socially inconsiderate professors and other such elements from the new left of the 1960s and 70s that had the effect of alienating workers, but the same was true of the “‘left’” communists that Lenin targeted.8 Indeed, the Eherenreichs added, and we might guess that Lenin would concur, working-class anti-leftism often “comes mixed with a wholesale rejection of any thing or thought associated with the PMC—liberalism, intellectualism, etc.” (NL 20). Sound familiar? The PMC, thus, is a class not defined by its role in production, like the proletariat, or its role in exploitation, like the bourgeoisie, but instead, as the Ehrenreichs’ original 1977 definition had it, by its role reproducing the cultural or ideological conditions necessary to maintain the relations of production and exploitation between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie (PMC 13). In short, the PMC are the unwitting ideologists of a bourgeoisie that has liberated itself from the dirty work of manufacturing consent.

A couple of months after his “Infantile” essay Lenin would describe the corrupting, culturalizing influence of the “petty-bourgeois-democratic” or “‘left-wing’” progressives this way:

The workers of all lands are ridiculing the wiseacres, not a few of whom call themselves socialists and argue in a learned or almost learned manner about the Soviet ‘system,’ as the German systematists are fond of calling it, or the Soviet ‘idea’ as the British Guild Socialists call it. Not infrequently, these arguments about the Soviet ‘system’ or ‘idea’ becloud the workers’ eyes and their minds. However, the workers are brushing this pedantic rubbish aside and are taking up the weapon provided by the Soviets.9

The gist is that what we now call the PMC (but perhaps, following Lenin, should instead call the “‘wiseacre’ class”) posits itself as reasonable or democratic or liberal or progressive or socialist or communist or anarchist or revolutionist or whatever—it doesn’t matter—but only ever does so scholastically or pedantically. Think of the defensively technocratic Marxologist or TED-talker, the fetishistically critical hermeneuticist of suspicion, the dissembling neoliberal ecosystem or actor-network theorist, or the symptomatically other-oriented, archly “creative” street protester as types in point.

The long-brewing turn from the residual state-centered critical philosophy of Kant and Hegel’s day that still grounded Lenin’s strategies and policies to the alternating anti-statist and technocratic, critical and traditional theory that has come to take its place since Lenin’s time has taken on a new culturally specific role more recently. As Hal Foster put it in 1996, for example, “critical theory has served as a secret continuation of the avant-garde by other means: after the climax of the 1968 revolts, it also occupied the position of cultural politics, at least to the extent that radical rhetoric compensated a little for lost activism.”10 From the get go, social contradiction has been the defining feature of this critical-theoretical continuation of the avant-garde or PMC continuation of “petty-bourgeois-democratic,” “‘left-wing’” or “wiseacre” progressivism. Laying bare its class structure by collapsing the old distinction between high culture and the avant-garde, Foster called this contradiction its “double secret service.” As “a high-art surrogate and an avant-garde substitute,” he noted, it “has attracted many different followers” (RR xiv). Those followers have ranged from the bohemian to the brahmin, with a lot of intrepid capitalists and spirited anti-capitalists among the broader spectrum of art enthusiasts in between. Few of these enthusiasts have understood themselves to be—or act on behalf of—workers as a class. As such, almost none have been agents of substantive democratization.

Lenin’s main point was not that “‘left-wing’” communists were anti-vanguardist or anti-party or anti-“Leninist” in the usual ways we understand such positions, or even that they were anti-worker per se.11 Instead, he judged them harshly for being generally anti-institutional and particularly for being anti-parliamentarian, anti-trade-union, and anti-Soviet (or what at the time he called “non-Party workers’ and peasants’ conferences”). Such institutions, Lenin insisted, were not “systems” or “ideas” conjured out of thin air by activists but instead were living “human material bequeathed to us by capitalism.” As such, they were tools available for social change. Anything else—“abstract human material,” for example, or “human material specially prepared by us”—was not, he said, “serious enough to warrant discussion” (LWC 50). Only actually-existing networks of power produced by and for the capitalist relations of production were a realistic basis upon which one can fight for a better world, he argued—anything else is delusional or “infantile” because it is powerless. Lenin’s charge to his moralizing, more-despairing, more-left-than-thou comrades—predecessors of our alternately more-sardonic-than-thou and more-woke-than-thou PMC colleagues today—was, effectively, this: Grow up and address the world as it is, not from the standpoint of what you would wish it to be. Enough with your “systems” and “ideas,” your “theories” and “critiques,” your airy dream that “another world is possible.” It is time to get to work with the actually-existing tools at hand. In his own words, he called them “a group of intellectualists and of a few workers who ape the worst features of intellectualism” (LWC 57). Ouch.

***

Lenin was not alone in this appraisal. Think, for example, of Marx railing against the period intellectualism of his day, “the pompous catalogue of the ‘inalienable rights of man’,” insisting instead that “labourers must put their heads together, and as a class, compel the passing of a law,” and explaining that this “can only be effected by converting social reason into social force, and, under given circumstances, there exists no other method of doing so, than through general laws, enforced by the power of the state.”12 Indeed, we might speak of three key phases or versions of Lenin’s mandate to grow up and take on the world as it is: Marx’s foundational challenge to romantic anti-capitalism (think, for example, of the polemic in his “Critique of Critical Critique,” as he and Engels subtitled their 1844 screed The Holy Family), Lenin’s intermediate update to that challenge calling out the romantic anti-statism and anti-institutionalism more generally, and a third position that attempted to update Marx and Lenin that has a particular relevance for us today: Ernst Bloch’s challenge to romantic anti-communitarianism.13

Bloch encapsulated the problem as he saw it in 1935 with his well-known pithy summary statement “Nazis speak deceitfully, but to people, the Communists quite truly, but only of things” (HOT 138). The left’s theories and critiques may well be true but insofar as they are merely “systems” and “ideas” and not forms of direct engagement with and transformation of the existing forms of sociality and thus relations of power at hand, they speak in the PMC manner “only of things,” of cultural relations devoid of any coherent account of the desires vested in them or how to act on those desires. As such, they are vulgar, simplistic, reductive and naive. “In this way,” Bloch wrote about Brechtian montage but generally addressing the black-box systems theory of his day, “adventurous and distant romanticism move[s] into a cooled and experimental object; the distant scene of the action turns into a future one, anarchy (the best part of every exoticism) turns into a kind of laboratory, an open experimental space” (HOT 226). The romantic fullness of anti-systemic myth becomes the romantic emptiness of anti-intentional system. “It is a precisely upper middle-class void,” Bloch insisted, because “every thrust or idea from below is lacking” (HOT 217).

In a word, such a romantic anti-communitarianism is infantile. It does not address the world as it is because it does not address people as they are and instead rests in what Lenin called “abstract human material,” or the delusion of “human material specially prepared by us” or human nature presumed to be remade by lordly fiat as if it were an artwork or design problem for “engineers of the human soul.”14 It is managerial-speak, system-speak, theory-speak, critique-speak, art-speak that sophomorically and romantically presents itself as “the other side of ‘empty mechanics’,” Bloch said, and as such it is “under a curse of virtually confirming the hatred of reason among those who are proletarianized (as if all reason resembled the halved capitalist kind of today)” (HOT 139). In so doing, such an intellectualist leftism could never hope to win the support necessary to take power and instead could at best only dream of endlessly, tirelessly chattering on in the name of “critique” or “theory” together with that chatter’s painfully innocent twin, the ever-retreating “other world” that is said to be “possible.”15

So, how to speak at once “quite truly” and equally “to people”?

Bloch defined the parameters of such a project negatively: “since Marxist propaganda lacks any opposite land to myth, any transformation of mythical beginnings into real ones, of Dionysian dreams into revolutionary ones, an element of guilt also becomes apparent in the effect of National Socialism, namely a guilt on the part of the all too usual vulgar Marxism” (HOT 60). Oskar Negt would later summarize Bloch’s position about such mythical beginnings, Dionysian dreams and other such communitarian impulses this way: “either they will be appropriated by socialism or they will be added to the resources of its enemies—there is no third possibility.”16

From our perspective now, a similar “guilt on the part of the all too usual vulgar Marxism” can be fairly attributed to the likes of us for the successes of Putinism, Trumpism, Erdoganism and their ilk. Without question, conjuring our own innocence and “hoarding” it, as Catherine Liu would put it, is the single most infantile, romantic, PMC and predictable response to the world we find ourselves in today that we could have.17 Certainly it is true that in our day, as in Bloch’s era of rising fascism, we have produced no viable “opposite land” to myth, no effective means for transforming mythical impulses into real ones. As the “‘rationalizers’ of society” there is not a whole lot of good we can do, but even there—in the rationalizing that is our reason for being—we have failed.

***

This failure has been usefully surveyed and summarized by a number of observers. Thomas Frank, for example, writes with scorn of the “thick patina of expert-talk” which, he says, we stalwart loyalists of the PMC find “irresistibly beguiling” and serves to divert attention and desire away from any meaningful left political program.18 The sociologist Cihan Tugal provides an account that deserves quoting at length because it speaks pointedly to the diluted Dionysianism that we have produced in lieu of its socialist alternative:

The ghosts of incomplete revolutions, all the way from 1848 to 1979, are haunting the globe. A particular genie, the unpredictable middle strata, will continue to upset many hopes in the coming years. Sanguine and unidirectional investments in the ‘new middle classes’ have upheld these strata as the true bearers of democracy, post-materialism, the free market, and tolerance. Such false hopes peaked in the 1980s, but they still cloud minds. … Heavy new petty bourgeois participation in and leadership of the post-2009 revolts reinforced (but did not singlehandedly create) the disorganized (not really ‘leaderless’) and unfocused tendencies of post-1979 revolt. Entertainment, carnivalesque aesthetics, and politics were linked innovatively … [but the] aestheticized atmosphere of the revolt (with its unavoidable class character) turned out to be a double-edged sword—one edge facing the dominant order and the other the popular strata. … The most salient disposition of this class is neither simply tolerance (as in mainstream accounts) nor horizontalism (as in the current radical accounts). The key new petty bourgeois tendency is rather the monopolization of skill and the concomitant ‘ideology of the ladder’, contradictorily married to democratic and collectivist ideologies. The aestheticization of politics is among the core tendencies of this class … [which makes it averse] to organization and collective discipline … [and thus] devoid of the capacity to offer programmatic ways out of the crisis of capitalism.19

Needless to say, the foremost skillset monopolized by this middle stratum and made into an ever-shifting ladder that in equal parts intimidates and is resented by those who fall below the educational threshold of the PMC is the range of cultural competencies or the “thick patina of expert-talk” that grease the wheels of capitalist globalization. For our purposes, one particularly sharp area of cultural competency or domain of expert-talk is contemporary art, particularly insofar as it has merged with our current leading “creative” or carnivalesque brand of activism and its romantic anti-capitalism, anti-statism and anti-communitarianism.

Indeed, we might take the direction of the contemporary art that has dominated the global market since World War II to be our cutting-edge cultural expression of the bad faith postmodernist position identified by Wendy Brown:

So we have ceased to believe in many of the constitutive premises undergirding modern personhood, statehood, and constitutions, yet we continue to operate politically as if these premises still held, and as if the political-cultural narratives based on them were intact. Our attachment to these fundamental modernist precepts—progress, right, sovereignty, free will, moral truth, reason—would seem to resemble the epistemological structure of the fetish as Freud described it: “I know, but still…” What happens when the beliefs that bind a political order become fetishes?20

Brown raised this question in 2001 and, needless to say, after the rise of Putinism, Trumpism, Erdoganism and all the rest we now know the answer. Without a sustainable and compelling counternarrative to ethnonationalism, without a vision of, and feeling for, the modern freedoms created and enforced by the democratic state, without a lived investment in and fidelity to the political mechanisms that check the incessant market-amplified urge to consolidate wealth and power by any means possible, the radical upwards redistribution of wealth and political power and its instrumentalization of popular resentment now seems inevitable.

So, what is to be done?

The great realist and dialectical—or more simply, as Lenin implies, adult-like—choice made by Marx, Lenin and Bloch was to accept the conditions of power as they were in the worlds they inhabited rather than pining away for another world, or worse, conjuring new theories or systems or critiques, or worse still, falling back on the unalloyed purity of irony, cynicism, melancholy or despair. Marx looked to the heart of capitalism to find its gravediggers—hard at work in the newly organized sweatshops of factory production—just as Lenin looked to the heart of bourgeois democracy—parliamentarianism—and just as Bloch looked to the heart of Nazism with its vulgar and spite-filled myths of blood, soil and the like as the bonding agent for rising fascism.

Each of these were first and foremost objects of critique, of course, but more importantly they were also sites of power that, in theory, could be redirected away from alienation to enlightenment, from exploitation to freedom, and used as stepping stones to larger revolutionary aims. Arguably, Marx and his allies substantively if only partially succeeded in that redirection in their day just as Lenin and his allies did in theirs. In Bloch’s day, by comparison, the left failed to win the popular support needed to effectively counter the rise of fascism and capitalism both. As Tugal suggests, that failure continues to haunt us now.

***

So, what resources do we have in our actually existing world now that might be successfully repurposed toward the left goals of enlightenment, popular empowerment and socially-realized universal freedom? What are our equivalents to the factories which Marx came to see as unparalleled tools of class consciousness and Lenin’s parliaments which, as he put it, were “not only useful but indispensable to the party of the revolutionary proletariat” (LWC 61)?

Bloch said that what the left lacked in 1935 was a viable substitute for community-binding myth that could transform its alienated impulses into real ones. If the single greatest myth of Marx’s and Lenin’s long nineteenth century was the collapse of enlightenment reason into technocratic reason and political progress into technological progress, the single greatest myth of Bloch’s twentieth century, as with our twenty-first, is identity. Of course, our notion of identity is less bound to the national cultures of the early and middle twentieth century with their national languages, origin stories and aspirational dreams, and instead are more tied to the spatialized notion of community. Like nationalism, communitarianism is defined by social ties and therefore bloodlines but with more elastic, less-defined geographical restrictions and thus greater potential for more varied, experimental, dispersed and potentially fertile and far-reaching networks. In a word, our twenty-first-century identitarianism is defined by “glocalism.”

So what can be done with the sense of community we have, but understood as a potential political resource in the dialectical manner of Marx’s approach to the factory and Lenin’s to parliament?

Without question, Eric Hobsbawm was right in 1996 when he said that the concept of “community” as it developed over the course of the twentieth century into a pseudo-sacred ideal was “a new and dangerous element” that has had devastating consequences for any left political project. More and more after World War II, the principle of community has come to displace the role of political parties and trade unions as the leading formal principle actively organizing (or disorganizing) collective self-imagining. This is nowhere more visible than in the rise of left-liberal NGOs (although contemporary art may give them a run for their money) and nowhere more consequential than in the rise of the “Anti-Communist International” or clandestine network of paramilitary intelligence operatives and death squads that conduct hidden foreign policy by extra-statist means.21 “After a period of virtually unbroken advance from the late eighteenth century to the 1960s,” the state and its institutions have “entered an era of uncertainty, perhaps of retreat,” Hobsbawm concluded. “A phase of state development which lasted for about two centuries,” he warned, “is now at an end” and what we are left with is nothing more or less than “barbarism.”22 Where the nation had been an engine of state formation, the principle of community, he argued, has been the social-theoretical motor driving, or, better, enabling, its collapse further and further towards the nightwatchman state that neoliberals have long argued for and the neofeudal system of privatized governance that white supremacists, dark enlightenment enthusiasts, and other unapologetic advocates of birthright inequality pine for.

However, if our provisional analogy holds, community—like the factory for Marx and the parliament for Lenin—might best serve us as both a primary object of critique and at one and the same time that which most needs to be re-theorized and reactivated for left political ends. This observation by journalist Matthew Cunningham-Cook offers us an entry point into thinking through this question:

Union organizing campaigns often depend on reservoirs of working-class consciousness in the workers they seek to organize. But with unions now spread so thinly across the country, and almost completely absent from many states, particularly in the South, organizers often have to build on other forms of consciousness—community, racial, gender. That’s why the point of entry to organizing workers—whether in a union or, given all the obstacles to forming unions, in other kinds of groups—may depend more on establishing a good record for the group in the community.23

It is a simple, commonsensical point, and in fact one that has long been a key tool for organizers but nonetheless is routinely lost in the “thick patina of expert-talk” of the PMC, the language of a left that routinely loses its capacity for dialectical thought in the heady romanticism of theory and critique despite ample evidence to the contrary.24

The Ehrenreichs said the same thing: a “wholly vocational approach to class leaves out everything else which shapes a person’s political consciousness and loyalties—their experience of other classes, their family and friendship ties, their experiences as a consumer of services, their notion of their ‘community’” (R 325). That “shaping,” they insisted, is the only arena in which organizing might stand a chance. Myriad others have made the same point many times over the years even if they are not always heard, but I’ll cite just one further example. Labor organizer Jane McAlevey puts it this way: “organic ties to the broader community form the potential strategic wedge needed to leverage the kind of power American workers haven’t had for decades.”25 For example, if “faith matters to workers,” she explains, “it has to matter to unions” (NS 68).

The working assumption is that organizers and those seeking to be organized are much more likely to be successful if they organize people in their lives as they are rather than as they might wish them to be. By “systematically structuring their many strong connections—family, religious groups, sports teams, hunting clubs—into their campaigns,” McAlevey argues, organizers have much more actually-existing social power at their disposal than if they address them only as workers (NS 28). In the process, community is rescued from its alienated status as mere culture—that is, as a picturesque bearer of reified identity—when it enables the collective exercise of political will. Just as a worker-owned-and-operated factory holds out the promise of redeeming the factory form, or a constituent assembly bears the promise of redeeming the parliamentary form from, as Lenin had it, deciding “once every few years which members of the ruling class are to repress and crush the people,” so the systematically structured political organization of the community form bears the promise of redeeming a culturalized and thus balkanized identity-centered communitarianism.26

If we accept Brown’s premise that state and individual sovereignty alike “require fixed boundaries, clearly identifiable interests and identities, and power conceived as generated and directed from within the entity itself” and that in our day “none of these requirements is met easily” then it would be a fool’s errand to prematurely invest too much political capital in the old institutions of the citizen and state apparatus (PH 10). One can conjure all the images of revolutions and revolutionaries one likes without much reasonable hope of gaining sufficient popular support to change anything. How we came to this condition of emptied modern subjects and emptied modern institutions is another question and, anyway, doesn’t matter.27 Our doubt about the modernist narrative of progress and the social and psychological structures that once founded it is what it is.

***

With the future foreclosed, there has been a tendency to look to the past instead. As one historian has put it, “liberals today are more committed than ever to a passionate remembrance of things past,” but instead of looking backwards to bring usable political insight forward into present action, they “now travel in the opposite direction, from present injustice to historical crime.”28 Origin narratives can guide in the same way progress narratives do by setting a direction, of course, but they typically produce two codependent problems—an undue and undemocratic sense of entitlement and an overwrought and politically ineffective sense of grievance—both of which exacerbate identitarianism and thereby undermine the necessary conditions of possibility for political organization. For a long time now, in the wake of our lost access to futurity, this has been our default approach to self-understanding in the name of identity, ontology, bare life, affect and myriad other such futile reaches for the primordially real. But as Brown observed, these are our fetishes—they “make a cultural or political fetish out of subordinated identities, out of the effects of subordination”—and as such are little more than vestigial yearnings from the past serving ideological ends in the present (PH 26). They have none of the emergent force that factories and parliaments once did or that, in principle, community might have for us now.

So, if the factory and the parliament were both at once the scene of the crime and a requisite hammer of justice for Marx and Lenin—“not only useful but indispensable to the party of the revolutionary proletariat,” as Lenin had it—what is the specific work that community can do?

There is its role as a stepping stone to the class consciousness necessary for labor organizing in the manner outlined by Cunningham-Cook, and there is its role as a medium of available oppositional power outlined by McAlevey, but we might also point to a third, more ephemeral and more challenging but nonetheless foundational role. This too is very much part of the history of thought and practice but is also a tool that the left has largely relinquished to the right, and—again and again—with devastating consequences. Hegel called this third role “the domiciliation of the divinity”29 and described the work that it accomplishes this way: