Alden B. Dow is remembered today as a talented architect who adapted Wrightian principles to design modern homes for the midcentury good life, many in his hometown of Midland, Michigan. But Dow was also a prolific amateur filmmaker who ultimately wished to be remembered as a philosopher (fig. 1). Some of his better-known films include two made at Wright’s Taliesin—a black and white film, shot during Dow’s apprenticeship with the master in 1933 and a stunning Kodachrome film of a 1946 trip with his wife to Taliesin West in Arizona, featuring rare footage of Wright himself (fig. 2). These films, which have circulated largely in the service of Wright’s fame as an architect, theorist, and teacher, are just a tiny fraction of the approximately three hundred films produced by Alden Dow from 1923 through the 1960s: travel films and home movies, but also philosophically-oriented experimental films and a host of architectural films. To honor Dow’s legacy and career, some of them are regularly screened today in a small 16mm theater of the architect’s own design in the basement of the Alden B. Dow Home and Studio in Midland, Michigan, as part of that institution’s public outreach and educational mission. Preserved in the archive, the films survive to exemplify the singular creative vision and, yes, philosophy of their maker.

Perhaps most striking about this output today is less what it proves about Dow’s individual artistry, however talented this architect-filmmaker-philosopher was, and more what it reveals about the enabling material conditions of this multi-hyphenate creativity—namely, the explosive midcentury growth of the petrochemical industry. As the youngest son of Herbert H. Dow, founder of Dow Chemical, the Midland-based industrial giant, Dow built a practice as a professional architect and amateur filmmaker that was conditioned by his proximity to the operations and aspirations of the family firm. His family’s wealth and connections linked Dow’s filmmaking through what film historian Haidee Wasson has called the midcentury’s “network of portable machines” to international aesthetic movements, global economic forces, and powerful midcentury institutions.1 Dow’s amateur filmmaking practice was para-industrial, enabled by the Dow fortune and often taking as its subjects architectural commissions that were forms of patronage for Dow Chemical managers, executives, bureaucrats, and workers. While not corporate commissions per se, his films are a sign of petrochemical largesse in the displaced, quasi-superstructural form of Alden B. Dow’s passionate hobbyism.

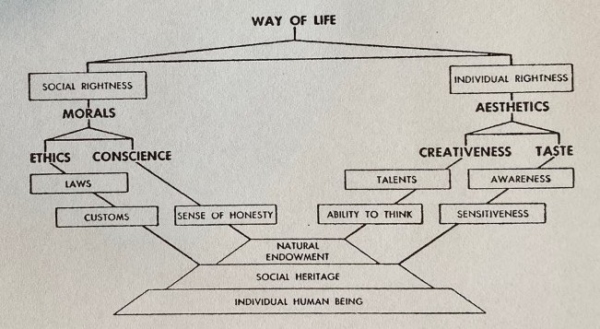

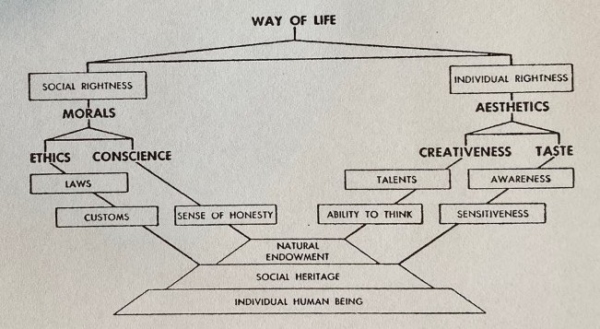

We can observe a similar overdetermination in Dow’s philosophy, especially around a series of intersecting conceptual abstractions like “creativity,” “individualism,” and “home” in his writings and public talks—often for audiences of architects and architecture students and illustrated by his films. Dow’s understanding of creativity itself was powerfully shaped by the innovation, ambition, growth, and increasingly environmental scale of his family’s rapidly expanding company. At Dow Chemical, physical nature proved dazzlingly plastic; Dow chemists understood their work in the production of new synthetic materials as acts of exemplary creative agency. Alden Dow was fascinated early on by the novel materials of the petrochemical industry and saw them, in the wake of his mentor Wright, as essential to an organic architecture of the future. As intersecting modes of organic design, Dow’s architecture and films intertwined with a wildly innovative, often toxic petrochemical industry that was swiftly changing which substances, consumer products, and media counted as “nature” or “natural” in the first place.2 Dow documented this terrain of chemically enabled architectural experimentation and creative agency in 16mm films like Bay Gas Station (1960), for which he designed a parabolic concrete roof sculpted in Styrofoam, and Dow Test House / Carras House (1961), a film of a Dow Chemical commission to design a prefabricated research test house for the company’s new products.

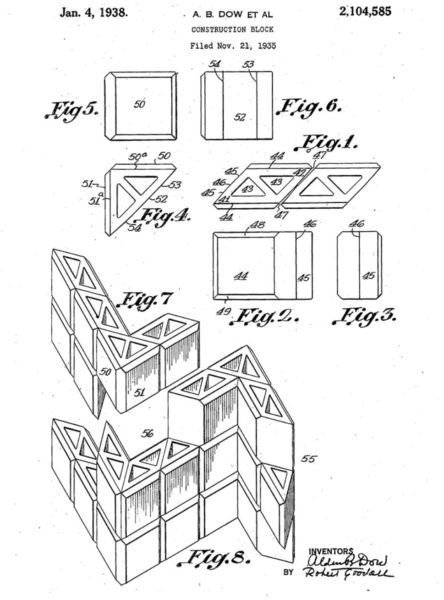

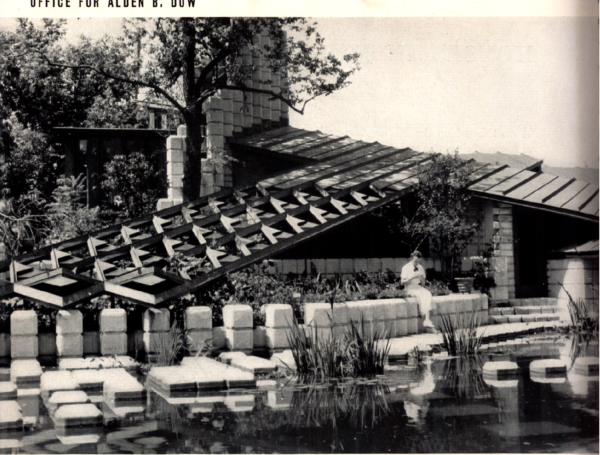

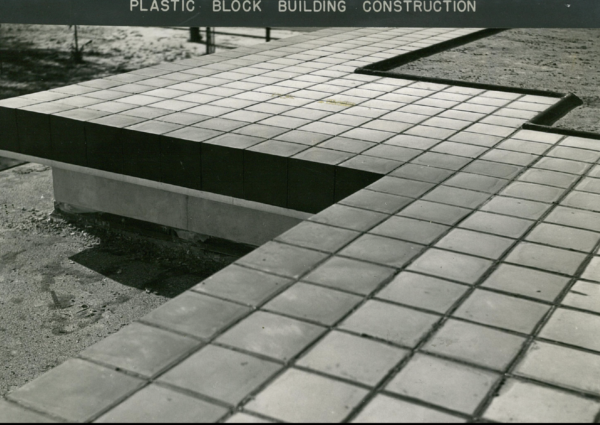

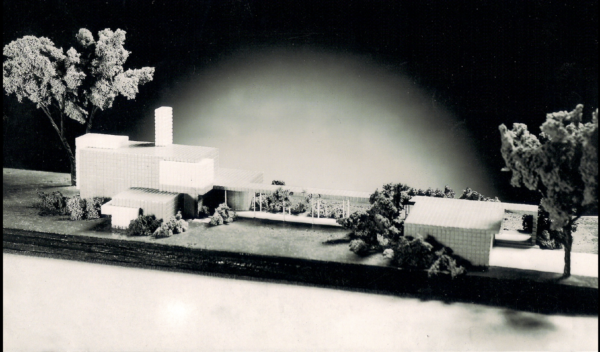

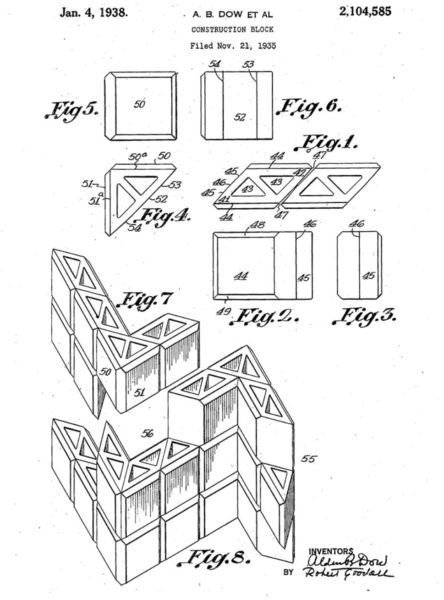

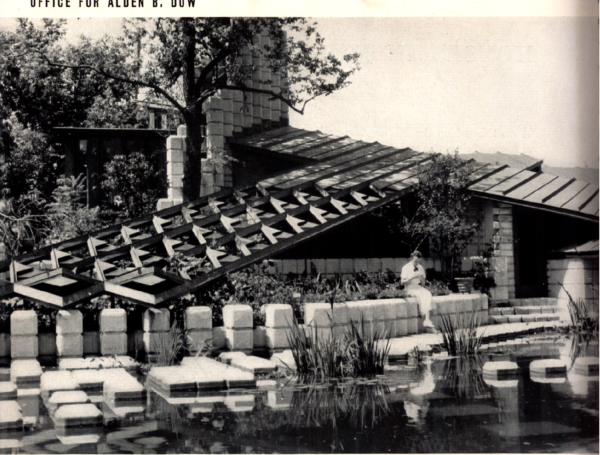

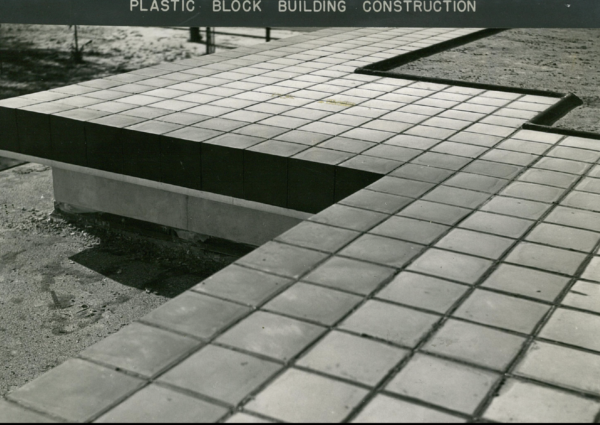

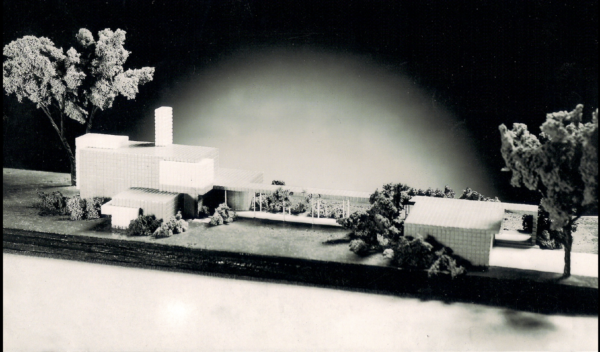

Making the modern home a space for creativity and individual growth was the primary aim of Dow’s domestic architecture, at the core of his concept of the good life as it might materialize in architectural form. In Alden Dow’s houses, these abstractions became concrete—sometimes literally so, abetted by new Dow product applications. As he clarified in his public lectures, filmmaking was a related medium of individual creative expression, much like his experimental architectural designs in modular Unit Blocks (patented cinder blocks made from the industrial refuse of Dow’s coal furnaces) (figs. 3 and 4) or clad in colorful Dow Ethocel plastics (fig. 5). And creativity for Dow—as exemplified by an amateur film or well-tended garden—was the core attribute of individualism but also, more expansively, a character trait of liberal-democratic societies, a vital Cold-War virtue. Similarly, his professional designs on the ideological shape and material texture of the postwar good life, like his multimedia experimentation, was a part of a midcentury design dispositif of international scope.3 This broad constellation of knowledge and discourse, material practices and media, joined designers and architects to corporate managers and social scientists in the work of meeting the vexing challenges of the postwar world order—including the management of postwar industrial expansion and the booming economies of the Global North.

Like many of his contemporary architects and designers, Alden Dow—architect-filmmaker-philosopher—was a technician of postwar happiness, working across various media and at multiple scales. As in the midcentury design dispositif more broadly, the intertwined media of creativity could be upscaled precisely because Dow understood film to operate in the service of human techniques, those deeply historical practices, forms, and processes that organize people and nature, whether in discourses of architectural design, pedagogy, or the planning of “housing” in the social aggregate.4 Folded into a multimedia repertoire of Dow’s design technics, 16mm film allowed him to test, project, and pedagogically model his evolving theories of creative agency.5 Such creativity demanded human technical intervention in natural processes (as we might expect from a Dow scion), but it also embedded human activity in a broader field of forces, processes, and technics that dialectically shaped and reconfigured it.

The proximity between Dow’s amateur camera, his design philosophies, and the sheer growth potential of the midcentury petrochemical industry is perhaps closest in his work in the Texas Gulf Coast during World War II. Beginning in 1941, Alden Dow carved an entire town, Lake Jackson, Texas, out of a coastal swamp as a grand design experiment in modern, low-cost communal living—for the workers at Dow Chemical’s new magnesium and styrene plants in Freeport and Velasco, built quicky during wartime mobilization with Dow’s purchase of 1,000 acres of resource-rich land in 1940. I say “Dow carved,” but this phrasing belies the complex assemblage of agencies and historical determinants, policies and technics, that were the material conditions of possibility for Lake Jackson. The vast project, a private-public partnership backed by the Federal Public Housing Authority and the Federal Housing Administration, allowed Dow to realize his architectural philosophies on the scale of the small, model modern town, all while solving a housing crisis for workers precipitated by Dow Chemical’s explosive wartime growth and the ensuing pressure to fill contracts for magnesium with the U.S. and British governments.6

In what follows, I approach this ambitious project in wartime housing and the design of the postwar good life across the various scales traversed by Dow’s camera and his design practice more broadly: from the Midland modern home to the Gulf Coast town, from modest cinder block to mass housing, from amateur 16mm to the glossy corporate public-relations image repertoire of Dow Chemical, from Dow as a singular agent—and theorist of an organic architecture of individualism—to Alden B. Dow’s enabling ecology. Because my analysis seeks to historicize the sheer range of Dow’s design technics across media, I explore the intersection of his filmmaking with his domestic architecture and planning work, as well as his written theories and public talks—the latter often accompanied by his films. In this context, a film like Freeport-Lake Jackson (c. 1940–44), which Dow shot to document his Texas work, becomes newly legible within Dow Chemical’s own developmental efforts on the Gulf Coast.

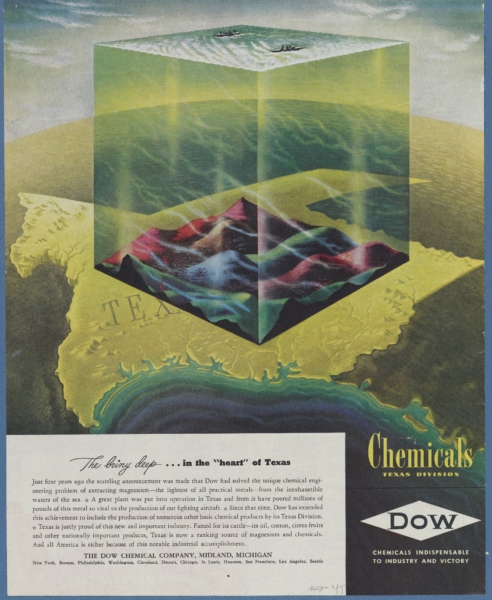

By virtue of its organizational adjacency to his family’s company, Dow’s film—documenting a grand, labor-and-capital-intensive feat of wartime resource extraction—offers film and architectural historians a fascinating case study in infrastructural and extractive media.7 Here, Dow Chemical’s Texas Division was both building and mediating infrastructure on several scales simultaneously: the production of vital Allied war materials, the provisioning of housing for defense workers, and more profoundly, the making natural and seemingly inevitable of the substrate of the postwar good-life in the products and byproducts of petrochemical modernity (fig. 6). In Freeport-Lake Jackson, modern architecture, moving-image production, and extractive processes of various kinds intersected in the production of value for both for Dow Chemical and Alden B. Dow himself.

The result is an example of what I’ll call a “development film,” which bound filmmaking to the extractive work of real-estate speculation. Film historian John David Rhodes has recently demonstrated how the representation of houses in commercial cinema positions spectators before images of property, offering vicarious forms of alienated relationships to the home as private property in the process. Through the home’s metonymic power, spectators can enjoy the “dreams of privacy, enclosure, freedom, autonomy, independence, stability, and prosperity that animate national life in the United States.”8 A non-theatrical amateur planning film like Freeport-Lake Jackson does something similar. It was shot by a property owner who, as we’ll see, had both serious conceptual designs on “the home” as good-life metonym and substantial material investments in the represented property.9 More specifically, Dow’s film also positions its spectator before the home—as desirable accumulation of capital, as design object and ideal—in its moment of emergence and growth, in the processual, speculative key of development and planning, and in a period of significant uncertainty about the returns on the investments of its maker. As such, Freeport-Lake Jackson mediates the historical moment in which conditions of wartime urgency gave way to prognostication about how best to capitalize on the closely linked postwar futures of the chemical industry and the modern home—of a democratic way of life made better by chemistry.

I.

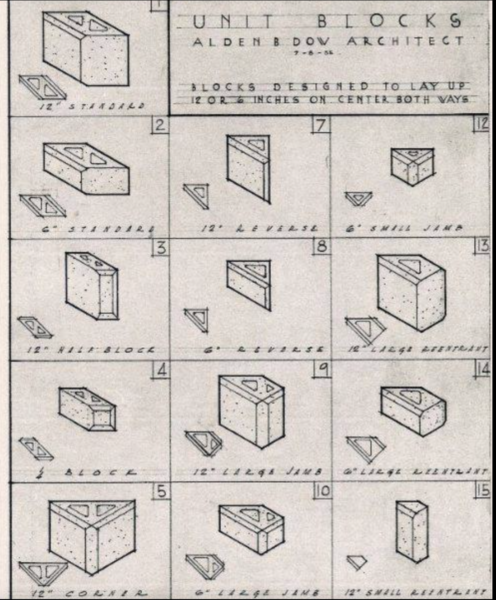

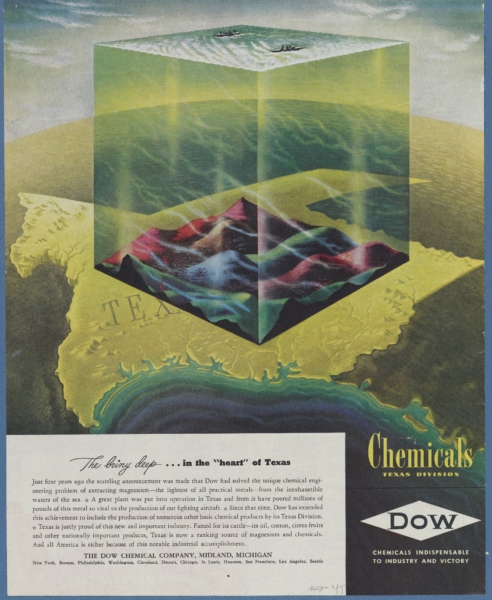

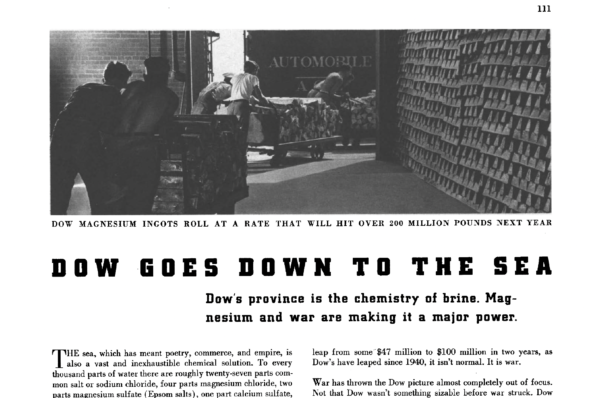

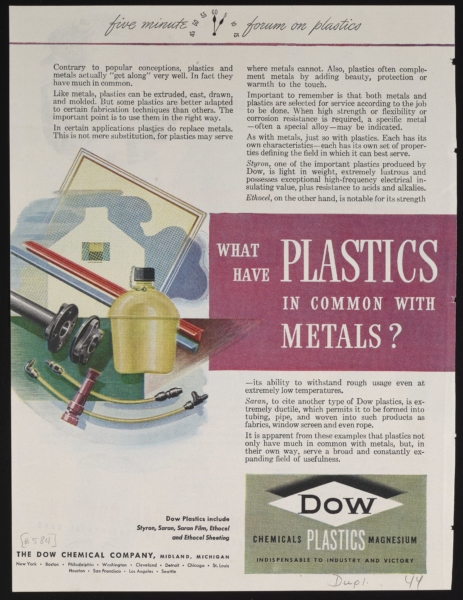

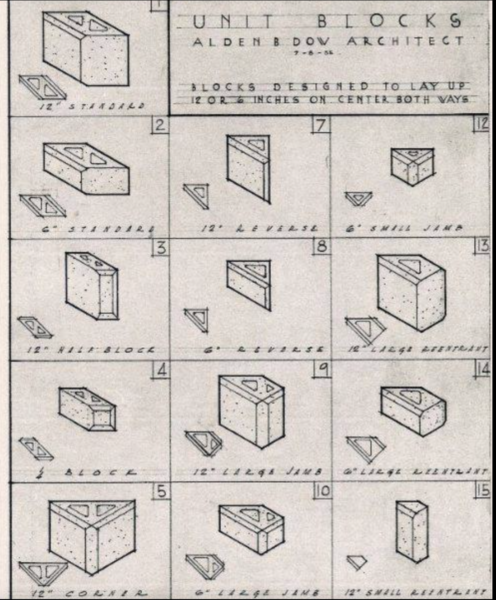

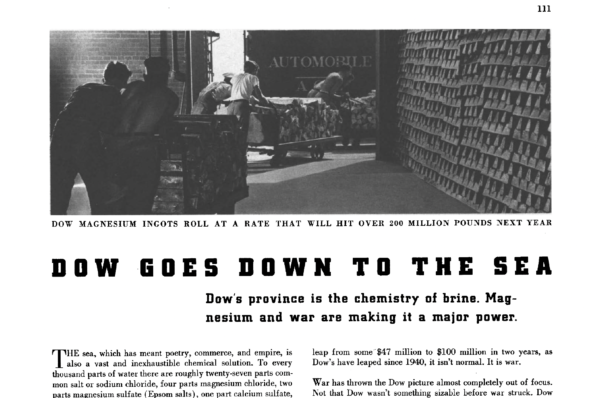

In 1941, when Dow began his Gulf Coast design work, Dow Chemical was rapidly expanding its operations, on pace to join the three industrial giants (du Pont, Union Carbide, and Allied Chemical) in shared dominance of the U.S. chemical market. Founded by Alden Dow’s father Herbert H. Dow in 1889, the Dow Chemical Co. had built its brand on the chemistry of brine and the extraction of basic halogens—chlorine, bromine, iodine—from the vast brine deposits, salty residues of ancient seas, buried deep beneath the surface of Michigan farmland. These elements, as an admiring feature in Fortune magazine explained, “put Dow in a basic field of chemistry, resting on cheap, almost limitless natural resources—a field that by concentration and continuous research might open out endlessly” (fig. 7) (DTS 112). Between 1937 and 1941, Dow was the nation’s fastest growing chemical company, with a rate of 26% per year.10 By 1942, Dow’s sales had doubled in two years from $47 million to $103 million, with 40% coming from industrial chemicals, 10% from pharmaceuticals, 25% from newer products like “Dowicides” (insecticides and germicides) and Dow plastics (Ethocel, polystyrene, and Saran), and 25% from the production of magnesium, what the company dubbed “Dowmetal” (figs. 8 and 9) (DTS 111). The source of this hypertrophic growth was not just the inspired vision and canny corporate strategy of its leaders—first Herbert Dow, then his eldest son Willard, following the founder’s death in 1930—or the ingenuity of Dow chemists, but rather the “the expansive force of war” (DTS 112).

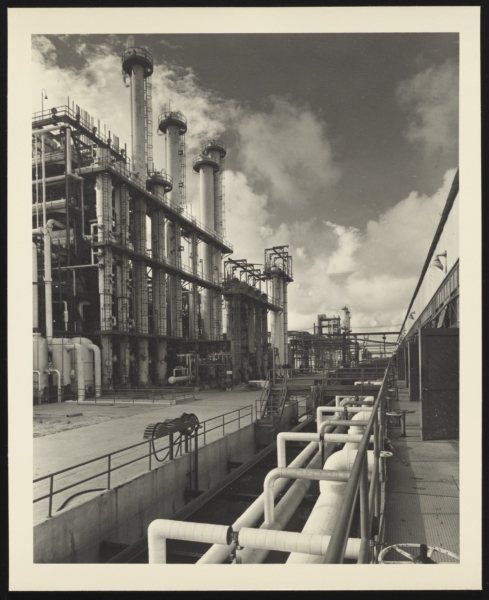

Judged from the vantage of Fortune’s wartime coverage, magnesium extraction was Dow Chemical’s “most portentous development” (DTS 111). The firm’s production of the structural metal had begun following World War I, and the subsequent global conflict had sparked a surge in demand for magnesium as a lightweight material for swifter Allied aircraft. As the likelihood of U.S. involvement in the war increased in the late 1930s, Dow Chemical cannily anticipated an increased demand for bromine, styrene, and magnesium production that would not be met by its Midland plants and so created its Texas Division, helmed by Dr. A.P. “Dutch” Beutel, building a series of plants in Freeport, Texas, beginning in 1940 (GC 175–85).

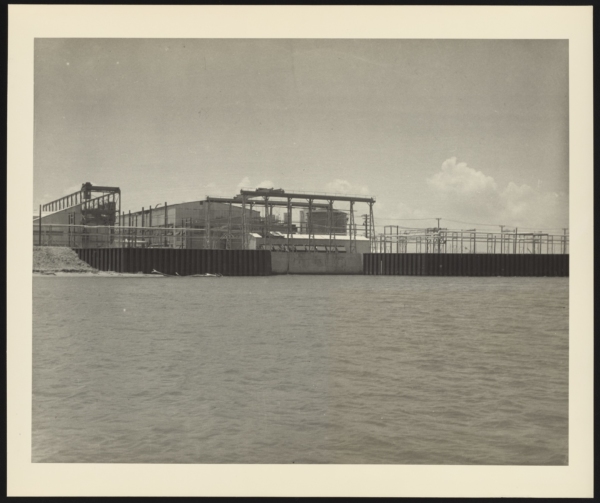

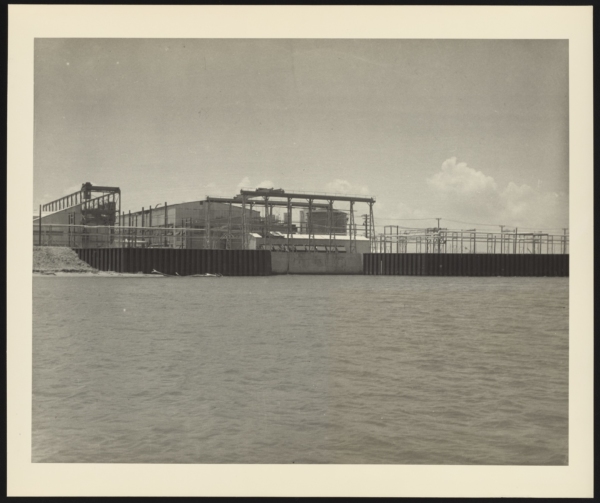

The resource-rich location, sixty miles south of Houston, was chosen for its proximity to cheap energy, abundant oyster shells for lime production, available fresh water from the nearby Brazos River, ocean port facilities, and what Dow corporate historian Ned Brandt called a “bounteous supply of low-priced land,” as well as a “local community eager to welcome a new industry” (GC 178). Freeport’s first magnesium-from-seawater plant (Plant A) began operations on January 21, 1941 (fig. 10). Remarking on the mining of the oceans, this technical feat of chemical engineering, Willard Dow would later gush, “There is an epic quality involved in the peopling of a flat, narrow tongue of waste land with strange shapes of structures, and having them combine to take a ladle of gleaming metal out of a curving, white-capped ocean wave. Not even the old alchemists, in their wildest fantasies, got that far” (figs. 11 and 12).11

The CEO’s retrospective epic notwithstanding, Dow’s extractive alchemy in Texas had some help—notably from the deep pockets of the federal government. As France fell in 1940, Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, fixed airplane production at 50,000 planes a year—a staggering jump from 5,000 annually. When the Freeport plant started production the same year, Willard Dow began lobbying Washington to “boost U.S. magnesium production to 100 million pounds annually,” offering to expand Dow’s operations to meet this goal, with government aid, naturally (GC 242).12 Dow steadily converted its production to wartime manufacture for the U.S. and the British, whose plants could not meet their needs for aircraft construction. After the Battle of Britain, the Allies discovered that German bombers could carry such heavy, deadly loads due to their magnesium-alloy construction. Allied aircraft design would follow suit by shedding weight (figs. 13 and 14).

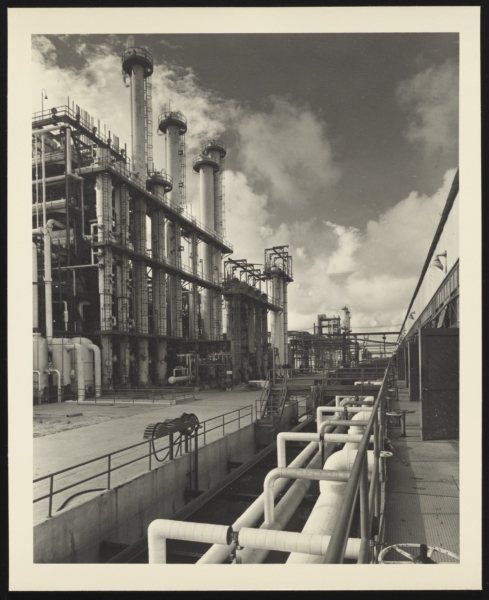

By late 1941, the Office of Production Management characterized Dow as the “No. 1 defense plant in the nation,” and shortly after Pearl Harbor, the Secretary of War offered Dow a $56 million contract to build a second magnesium plant (Plant B) in Velasco, Texas, Freeport’s neighboring town, which it completed in only eight months. Forming the Dow Magnesium Corporation to manage its lucrative wartime magnesium contracts with the U.S. and British governments, Dow also was also well-positioned at war’s outbreak as the U.S.’s only manufacturer of styrene for synthetic rubber production (Buna-S, made of styrene and butadiene). Under Beutel’s leadership, Dow built government styrene plants in Velasco, next to the magnesium plant, and in Los Angeles (fig. 15), and it contracted its technical know-how in styrene production to its industrial competitors (Monsanto, Koppers, Carbon and Carbide Chemical Corporation), now allied with Dow and the OPM in making sturdy tires for the war effort.13

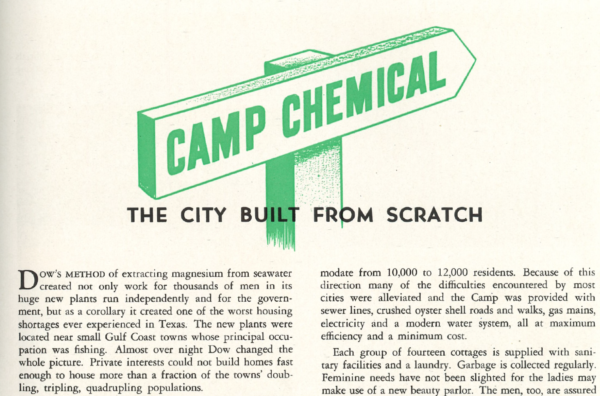

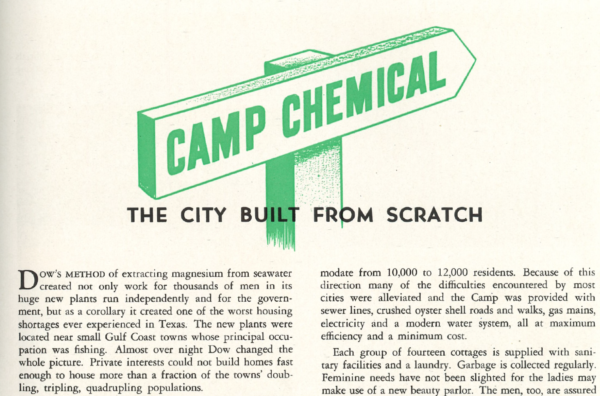

Dow’s expansive Texas operations also precipitated labor migration, as new employee and construction workers poured into the plants, and with it a significant housing crisis in and around Freeport. Enter Alden B. Dow, who readily accepted his brother’s invitation to design a solution to this problem. It came in several overlapping phases: first, beginning in 1940, the design and construction of several buildings and homes in Freeport, including a one-story hotel and over fifty modular, open-plan houses for Freeport plant managers and executives; then, as the housing crisis deepened with the construction of the second magnesium plant, the planning of “Camp Chemical,” a temporary workers’ community consisting of 2,300 bungalows—pre-fabricated cottages, built with lightning speed a little over a month in 1942, at the rate of sixty a day (figs. 16 and 17); and finally, as part of a corporate strategy to attract permanent Dow employees to Freeport, the design of a small town, which became Lake Jackson.

This Dow development scheme received significant government investment and was paid for in part through government appropriations under the National Defense Housing Act (the Lanham Act), a bill passed in October of 1940 to fund emergency housing for U.S. defense production workers. With financial support from the Office of Production Management for the construction of its magnesium plants and an additional $3 million from the War Production Board to build Camp Chemical, and notwithstanding its own substantial investment of capital in launching the Texas Division, Dow had an eye on the region’s “post-war operation, and wanted to plan for a permanent community sufficiently attractive to keep the turn-over in their plants to a minimum.”14 In other words, Dow’s housing strategy in the region was at once a pragmatic, patriotic response to the urgent needs of a nation at war and, with the Lake Jackson project, a more speculative corporate venture in postwar property development. The future value of this property would be bound to the Texas Division’s petrochemical future but also improved—that is, imbued with quality, its own extractive process—by Alden Dow’s modernist commitments.

In August of 1941, shortly after the Freeport plant began production, Dow Chemical had acquired a 6,000-acre tract of land eight miles inland to the northwest. Sold to Dow for $400,000 by a Houston-based doctor, the property that the firm would shortly develop through Alden Dow’s town planning and architectural design was the former site of an antebellum sugar plantation owned by Major Abner Jackson, a Confederate slaveholder. With his brother and Dr. Beutel, the architect scouted the property on horseback and selected the location for its high elevation and relative protection from hurricanes and coastal flooding. By October 1941, Dow’s design for the town was mostly complete, and the densely wooded site began to be cleared by a crew of Black, Mexican, and white laborers on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor.

Writing to a supervising engineer with the Public Buildings Administration in October of 1941, as Alden Dow was finalizing his plans, his brother Willard proposed “to handle this townsite by means of forming a company to take over and manage” it. He noted the firm’s plan to spend $100,000 on improvements to buildings in the next year, explaining: “It is our desire to develop this property in as constructive a way and as rapidly as possible, primarily with the hope of developing the property from the angle that the whole townsite real estate will tend to increase in value and that the desirability for homes will increase in proportion.”15 This strategy required hedging the company’s bets on what and where to build first in Lake Jackson and what to develop later, when the current crisis had passed and conditions for future growth were more clearly favorable.

With Alden Dow’s provisional plans in hand, the company approached the Federal Public Housing Authority, which agreed to develop the first section of Lake Jackson—one hundred duplex homes (two hundred separate family dwellings) designed by Alden Dow and with $878,000 in Lanham Act funds. The company, in turn, provided the business center, the school, recreation grounds, drug store and grocery, and other facilities, also designed by Alden Dow’s firm. The town’s managed growth, what Willard Dow called its “controlled development,” would work outward from the land devoted to the government housing and the property built with Lanham Act funds first.16 Dow ultimately designed every aspect of Lake Jackson: in addition to the government duplexes, five hundred single-family homes, plus schools, churches, recreation areas, commercial center, winding roads, and—in a nod to Dow’s cinephilia—its local movie theater, the Lake (fig. 18).

The result, as a 1944 feature in the government publication Insured Mortgage Portfolio put it, was “one of the newest and most unusual of the country’s war communities, built with both public and private funds, inhabited by citizens engaged exclusively in the unique industry of manufacturing a vital war metal from sea water, yet designed and built for permanence in spite of the fact that it is a one-industry town devoted at present to 100 percent of the production of war materials.”17 One hears in this characterization a kind of uncertainty about Lake Jackson’s future. What were the postwar prospects for a company town built, perhaps imprudently, in the urgency of a wartime boom or the fragility of a speculative bubble? And what would have attracted Alden Dow to this vast, risky project at this pivotal stage of the architect’s career?

II.

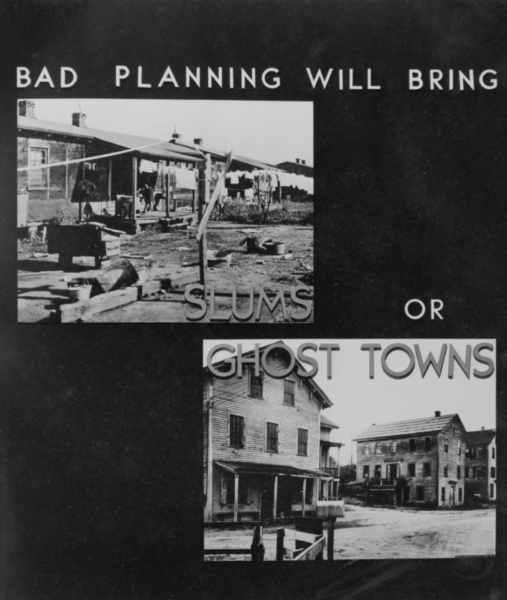

In the 1930s, Dow’s modern homes—many built with his patented Unit Block modules—came to national and international visibility through his association with Wright and the evolving interpretative frame of so-called “organic architecture.”18 But Dow’s domestic architecture was also read as the built environment’s quasi-natural expression of the seeds of capitalist prosperity sown in Midland by Dow Chemical. In this way, the question of modern private homes, and the kinds of individual clients who could afford them, intersected in the 1930s with the specifically political question of modern housing as a broader response to an urgent social need—to the provision of high-quality, low-cost housing as a responsibility of modern industrial democracies, or even a basic human right. This conceptual nexus of “home” and “housing” would prove decisive for Dow’s town planning in Lake Jackson.

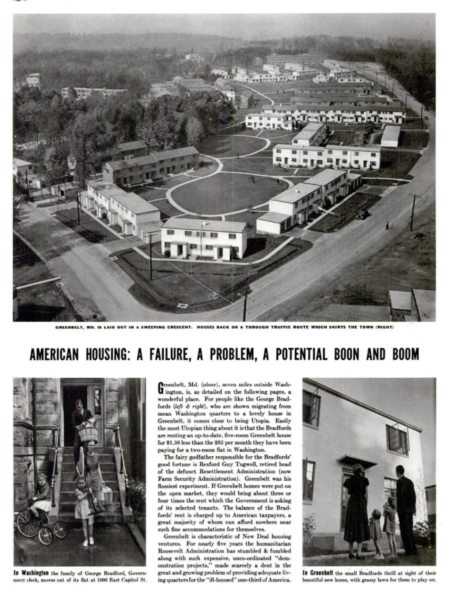

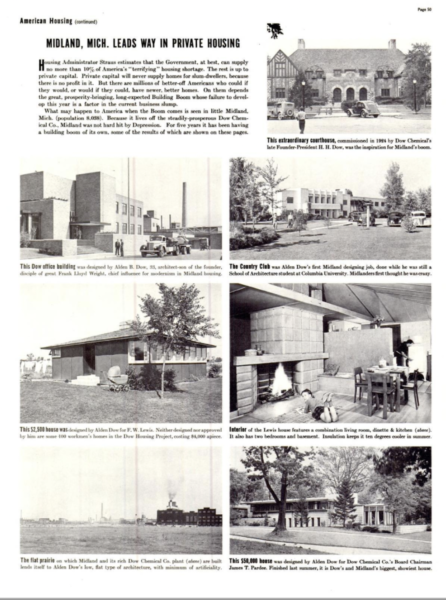

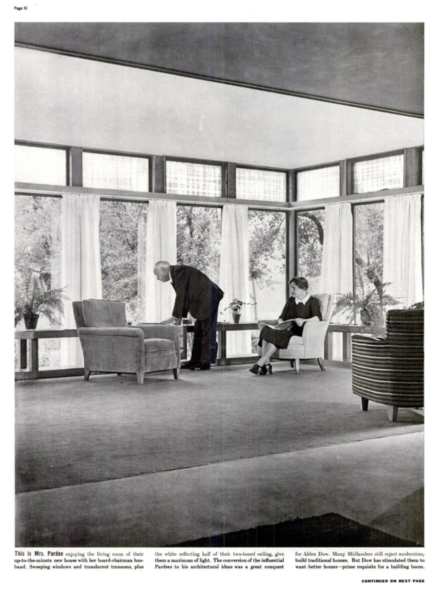

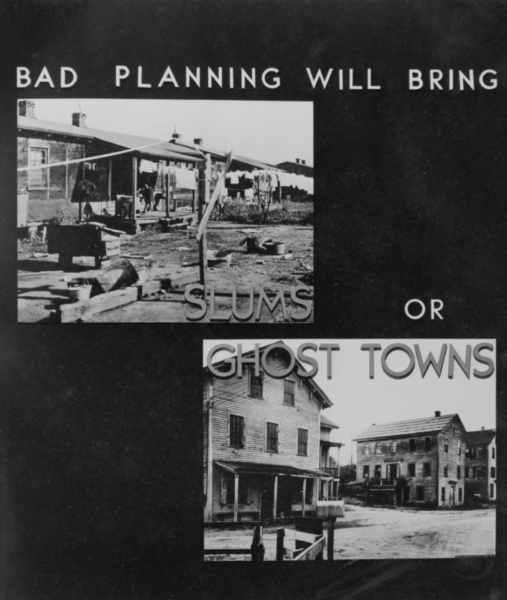

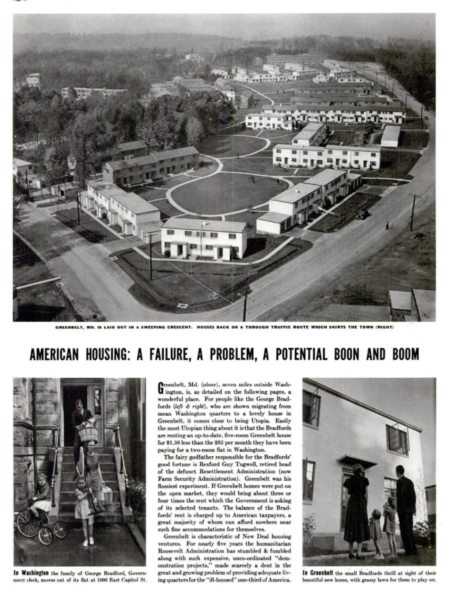

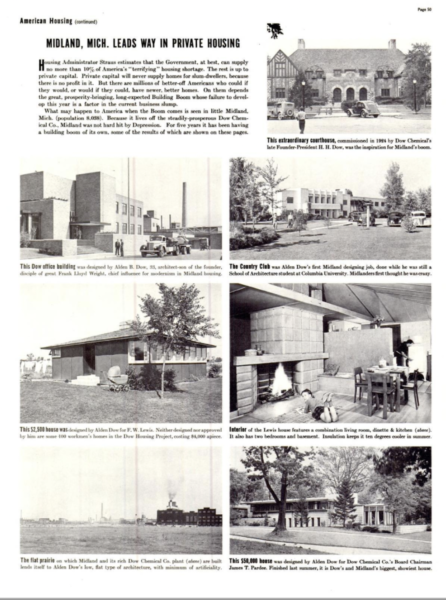

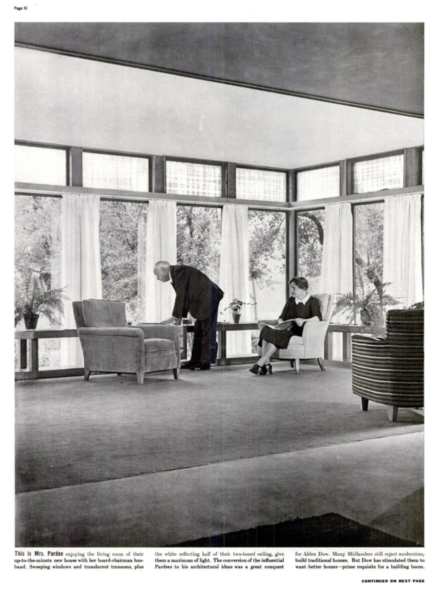

Consider the position of Dow’s work in a Life magazine “photographic essay” of 1937. The article aimed to promote some of the New Deal’s recent housing ventures around the Greenbelt towns program, featuring the government-sponsored, rent-controlled development in Greenbelt, Maryland (fig. 19).19 Dow’s architecture enters the narrative as an emblem of a salutary adjustment in U.S. housing policy circa 1937 from concentrated public authority and massive state spending at the national level, exemplified by Rexford Guy Tugwell’s work with the Resettlement Administration, to local management, in a section titled “Midland Leads the Way in Private Housing.” Dow’s work, including his first commission, the Midland Country Club, his Dow Office Building, and several of his homes, are adduced as the results of the town’s “building boom” over the last five years (fig. 20). Midland augurs a possible housing future for the country as a whole as it anticipates explosive economic growth: “What may happen to America when the Boom comes is seen in little Midland (population 8,038). Because it lives off the steadily prosperous Dow Chemical Co., Midland was not hit hard by the Depression” (AH 50). As one might expect from a Depression-era publication of the Luce empire, this envisioned future lies with not with the efforts of the “interventionist state” in housing policy.20 The state, the article argues, can only go so far in solving the housing crisis—providing only 10% of its supply, according to Nathan Straus, head of the new Federal Housing Authority. “The rest,” it continues, “is up to private capital. Private capital will never supply homes for slum-dwellers, because there is no profit. But there are millions of better-off Americans who could, if they would, or would if they could, have newer, better homes. On them depends the great, prosperity-bringing, long-expected Building Boom” (AH 50).

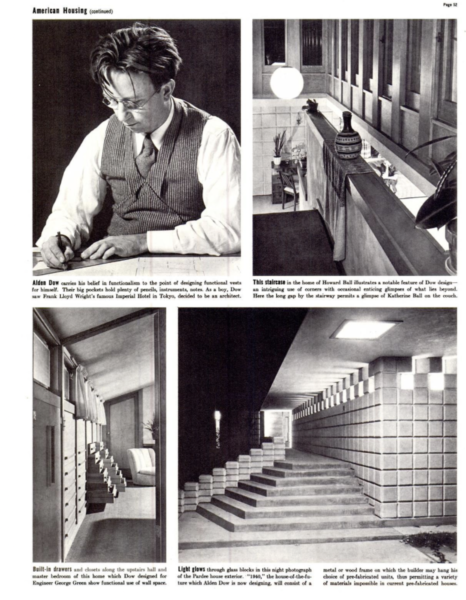

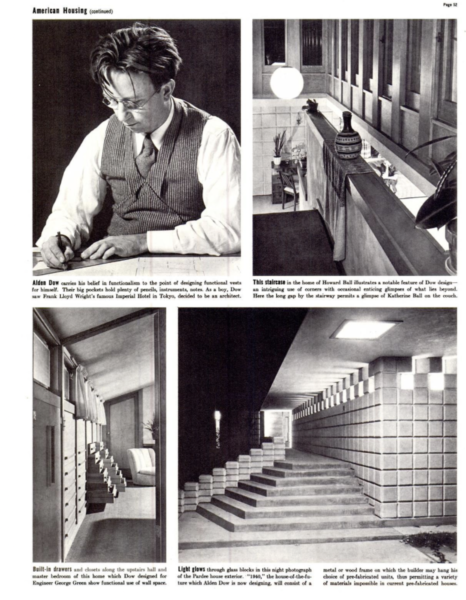

The selection of Dow’s domestic work here ranges from the Pardee house, a $50,000 Unit block home constructed for Dow Board Chairman James T. Pardee, aptly described as “Dow’s and Midland’s biggest, showiest house” (figs. 21 and 22); to a considerably simpler Unit block home for Howard Ball, in Dow’s sales department; to the F.W. Lewis house, Dow’s first experiment in low-cost housing, designed for a Dow accountant, and featuring a Unit block chimney and fireplace, built for $2,500 (AH 50). In the context of the article, this spectrum of Dow’s clients—not a “slum-dweller” among them, to be sure—speaks to modern architecture’s capacity to foster the conditions of a building boom across the broad range of incomes of “better-off Americans” by creating a market for newer “better homes” (AH 50, 51). The Pardees are photographed in their light-filled living room—with sweeping windows and translucent plastic transoms—in a full-page photo whose caption positions Dow’s genius as his capacity to produce a desire for modern living (figs. 23 and 24): “The conversion of the influential Pardees to his architectural ideas was a great conquest for Alden Dow. Many Midlanders still reject modernism, build traditional houses. But Dow has stimulated them to want better homes—prime requisite for a building boom” (AH 51). Dow, like all modern architects and designers, was in the taste-making business, and “quality,” though surely inherent in the nature of materials, was also the byproduct of canny salesmanship and rhetorical effort—more a value than a scientific fact.21

Midland, like Dow’s early career, was regularly framed as Depression-proof and thus became a sign of modernism’s capacity to stimulate a building boom. And yet systemic crises of laissez-faire capitalism during the 1930s posed significant challenges to the livelihood and self-understanding of professional architects in the U.S. Having lost approximately 90% of their business during the Depression, they increasingly complained about threats to their profession posed by builders, engineers, contractors, and the prestige of industrial designers—the streamliners—in the period. While the New Deal provided jobs for architects, as architectural historian Andrew W. Shanken has argued, it also presented new restrictions on the nature of that work, now undertaken within expansive bureaucratic structures (the WPA, the TVA, the Resettlement Administration) overseen by politicians, economists, and a new cadre of so-called “experts”—especially what Architectural Forum publisher Howard Meyers dubbed those “mystical gentlemen known as city planners.”22 Similarly, the onset of the war as a vast, logistical enterprise in building and design came with new government contracts at the start, but it also curtailed non-military building and, with Pearl Harbor, restricted essential materials. Perceived as “too artistic and individualistic, both liabilities in war,” especially compared to those practical, sensible engineers, architects reinvented themselves during the war as planners—not just of wartime building, but the socially necessary activity of planning the postwar itself (APCC 5).

Dow Chemical’s Lake Jackson venture was embedded in this speculative architectural culture of home-front anticipation that Shanken has dubbed “194X.” For Alden Dow, this moment offered the chance to frame his wartime work as part of a broader planning vision—future-facing, yet also urgent and socially responsible. Filmmaking, for Dow, was a crucial part of these intersecting processes of theoretical articulation and professional self-presentation as a multi-media experimenter, and it intersected as a practice with his acts of planning and speculation in Texas.

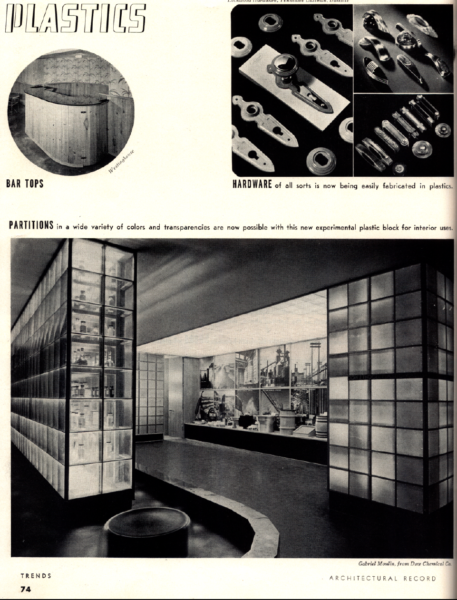

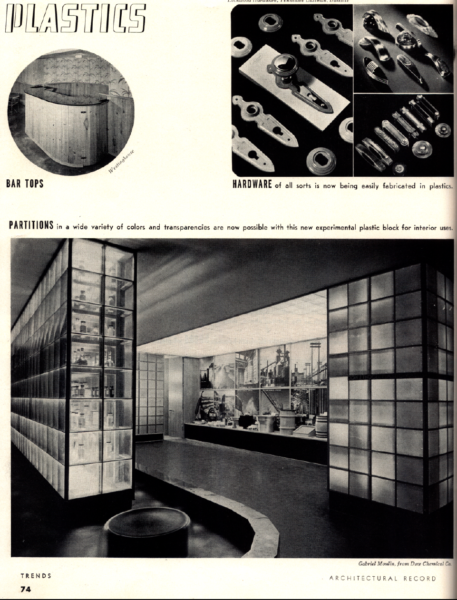

Beginning in the late 1930s, Dow began to illustrate his talks with his own photographs and 16mm films, inaugurating a practice as a kind of moving-image performer that would continue through the 1960s. In a 1939 address for the Michigan Society of Architects at the Detroit Institute of Arts, for example, Dow argued for the abiding sources of architectural form in nature in the style of Wright. For Dow, nature was not just “out there” but also embodied in human physiology—in sensation and nervous structure, which operated by observable optical laws. Designed to produce embodied effects on its user’s senses, architectural form would trouble the distinction between inside and outside, remaking the boundaries of the home itself, but also between the subject of sensation and the external world.23 The near-future “Golden Age” of architectural design, in which “architecture is a matter of exercising and relaxing the nerves and muscles of the body,” was augured by the new plastics manufactured by Dow Chemical (MDL).24 The MSA Bulletin notes that Dow was “on his way to California on business with the World’s Fair.” In fact, this was the San Francisco Golden Gate International Expo, where Dow designed the exhibition for Dow Chemical. It featured side walls of green, translucent Ethocel (ethylcellulose) blocks and a ceiling fashioned of opaque styrene plates (fig. 25).

Dow’s color cinematography becomes newly salient in the context of this lecture’s theoretical and aesthetic aims. “Photography being his hobby,” one contemporaneous observer noted, the talk ended with photographs and color films of Dow’s domestic architecture, chiefly of his home and office, and its natural analogues: “flowers, waves, trees, spider webs, drifted snow, clouds, sunsets, etc.” (MDL). As the MSA Bulletin observed, “The colored motion pictures were taken by him mostly in his own home and office during the past five years. He showed by flowers and plant life how color and form in architecture have parallels in nature.”25 In the context of his theoretical, putatively scientific account of the physiology of color, of course, Dow’s Kodachrome 16mm photography extends beyond documentation or a visual illustration of organic form. Moving images are projected as a theorical instance of the capacity of color design and picturesque composition to produce sensory balance, variety, contrast—and thus, relief from monotony. More subtly perhaps, the materiality of celluloid, with its basis in an industrially produced plastics and its emulsion another chemical miracle, reasserts itself in context of Dow’s comments on the nature of the firm’s new synthetic materials, though there is no indication that Dow drew attention to this.

Not all of Dow’s audience was impressed. The talk provoked a special letter to the editors of the MSA Bulletin from one irritated attendee, cast as a “Voice of the People Response”:

He gave a wonderful exhibition of his ability to take good colored movies. It takes skill and patience as well as the necessary time, money, and abundant subject matter to produce a movie such as what was shown … The audience must have concluded that an Architect’s life must indeed be interesting and filled with beauty, romance, and everything that makes life worthwhile. But we guys who have to scrape our ribs over a board and have to scrape up clients anywhere we can find them … [we think] it must be wonderful to be able to practice architecture without ever having to make a living at it.26

Ouch. While surely not representative of the talk’s reception, this minor masterpiece of professional snark swiftly materializes the conditions of possibility of Dow’s filmmaking—a practice here interpreted invidiously as a sign of his detachment from professional realities, of his privileged dilettantism.

The long knives of “Sniffy the Doper,” as the anonymous grump dubbed himself, were sharp enough to summon to Dow’s defense Detroit-based architect Wirt C. Roland in the next issue of the Bulletin, asserting Dow’s “individuality” in the practice of architecture. He noted, admiringly, that “few people in his position” (read: with his wealth) “would give [architecture] such devotion.”27 Indeed, Roland continues, the “effect on me of the colored movies which Mr. Dow showed to us that evening sufficed to put me almost in a trance. How many of us may have labored along back of the self-service counter of architecture, conscientiously and sometimes well. Then come certain moments when we really dream of cutting free of all inhibitions to solve our problems with imagination.”28 Dow’s films, like his aesthetic theories and his architectural practice, also signified to his peers an aspirational professional autonomy—an economic freedom to create unburdened of restrictions and formulaic solutions that most practicing architects in the 1930s could only dream of.

As a design technic, Dow’s film projection was unusual in its exhibition context. It was clearly not yet a common professional practice at Michigan Society of Architects events, though this would change. It is worth noting that one of the 16mm films Dow screened here, ABD Office Construction, 1934–39, documenting the process of building of his lavish home office and studio, included not just black-and-white and color footage of the home’s construction, complete with tracking shots meant to simulate various sensory experiences of movement through space, inside and outside the finished studio, but also a brief concluding abstract animation sequence (fig. 26). It depicts the icons of Dow’s unit blocks—first scattered and then neatly assembled. Given the time, labor, and technical skill displayed in their construction, Dow’s films were received as a novelty and a spur to the imagination, if not an implicit affront to the daily grind of struggling architects. In other words, films like Office Construction were read under the broader sign of Dow’s growing reputation for experiment and speculation, and perhaps a kind professional excess. By less generous attendees, this superfluity could read as a conspicuous consumption of time and resources by someone with plenty of both. Surely the studio film’s animation sequence only enhanced this dimension, especially as its subject was Dow’s own evolving brand. Though the talk wasn’t about film specifically, Dow was quite cannily associating the medium—especially the organic, life-giving qualities of animation often commented on by film theorists—with the futurity of his own formal idiom, bringing its material “plasmaticness” in the context of the lecture into alignment with Dow plastics.29

Over the next year, as his brother Willard labored to launch the Texas Division and build the Freeport magnesium plant, Dow would give versions of this same talk with his home movies again accompanying his speculative visions and offering tests of them as he framed his position on the vanguard of modern architecture as an art and an experimental science. For an appearance before Detroit Women’s Club that same year, Dow’s film screenings were accompanied by a live pianist playing Brahms.30 Adding to his showman’s repertoire, Dow “illustrated with a crystal ball how magnesium, a new plastic, is put together by nature as a pure material for building purposes.”31 This is an error, a telling elision. The substance wasn’t magnesium but either Ethocel or Styron, the two new lightweight Dow materials the architect was then using in tile and block form (fig. 27).32 He deployed Dow’s plastics in the translucent roof of a Midland bath house (fig. 28), for example; in the molded Ethocel interior wall units of Dow Chemical’s corporate headquarters in Midland (fig. 29); and, in its more speculative form, in the model house Dow designed entirely from plastic blocks, a “miniature glimpse into the future” (fig. 30).33 The model, the “House of Plastic Blocks,” also featured in the pages of the lifestyle journal California Arts & Architecture in 1940, on the cusp of its legendary reboot under the editorship of John Entenza. The model would appear again alongside “a colored motion picture and lecture” that same year during Dow’s talk at the Flint Institute of Arts as part of the architect’s lesson “that mother nature is a perfect engineer, builder, painter, and sculptor.”34

At the FIA and Women’s Club talks, Dow explained his ongoing architectural experiments not as gimmicks or signs of new marketable design trends but as properly organic lessons in light, heat, and the efficient engineering of climate for human comfort: “We should learn from nature in buildings. In the near future,” he speculated, “buildings will be made of materials that will absorb heat from the sun, making a natural heating plant. The plastic will be treated to absorb the ultra-violet light from the sun, so that it will heat through the night.”35 This recurring framing of the Ethocel house as a “natural heating plant” built of modular plastic cubes, “heated and air-conditioned by the sun,” and glowing like a lantern at night is an early, aspirational fantasy of green environmental design. The term “plant” is perfect, playing on the analogies between natural and architectural form at the lecture’s heart but also extending this organic model for thermal efficiency and modulation to the various plants of Dow Chemical’s sprawling extractive enterprises, then springing up like mushrooms all over. As Dow honed his reputation on the vanguard of modern architecture on the eve of his Texas adventure, Dow plastics and Dowmetal, much like the unit blocks themselves, became the building blocks of a new anthropocentric organicism. It was at home in the human’s most extravagant interventions in natural processes—processes it aspired to through the chemical engineering of second nature, whether in the domain of plastics, or the scale of the private home, or the company town on the brink of the postwar good life.

Modern homes, Dow understood, would exemplify this organicism, but so too could “modern housing.” The latter, implying up-scaled dwelling in the social aggregate, planned and mass-produced by liberal or socialist governmental agencies, was a rather different beast. The problem of housing had achieved a new national visibility in the period due to a concerted public relations effort, as Dow knew well. The coverage of his Women’s Club talk remarked on his contemporaneous role on the Michigan Housing Commission, and his FIA talk accompanied the “Houses and Housing” circulating exhibition then on display from the Museum of Modern Art, which had debuted in New York in 1939 as a section of the “Art in Our Time” exhibition. Conceived in conjunction with the United States Housing Authority, the MoMA show positioned the “modern individual home, built by private clients” as a “an important laboratory” for three discoveries essential to the pressing problem of “public housing”: the “development of the open plan, the use of new building materials and the creation of new and standard parts for the house, and the creation of a new style.”36

In this exhibition scenario, Dow’s amateur 16mm film of his own opulent home and studio, and his display of his model plastic house, were publicly displayed alongside the plans and models of the larger MoMA traveling show, including experimental houses by Paul Nelson and Bucky Fuller; a community center by Oscar Stonorov; a city plan by Louis Kahn; a model of the Pittsburgh Housing Authority’s development around a Pittsburgh coal mine; and the photographs and drawings of the housing projects of Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. This heady company, gathered around the vexing problem of “housing,” significantly reframes Dow’s private commissions and the Unit-Block-built privilege of his own remarkable house (and its filmic representation) as part an international experimental design lab for cutting-edge modernist solutions to urgent public housing needs. The show also strove to articulate didactically the broad spectrum of income levels of the contemporary housing market that Dow’s career to date had largely avoided but that his Freeport-Lake Jackson development projects would shortly have to negotiate: privately built homes, low-cost homes backed by FHA mortgages, and homes built entirely by the government funds under the U.S. Housing Authority.

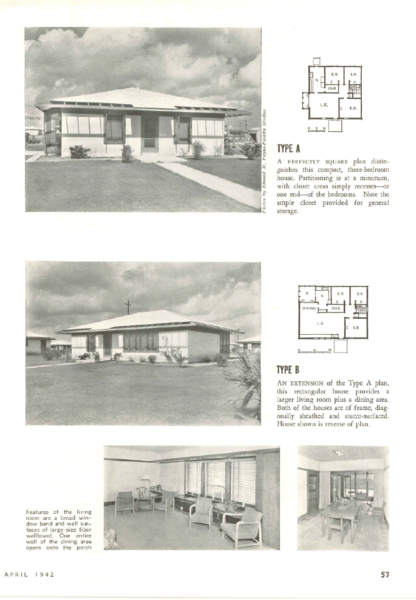

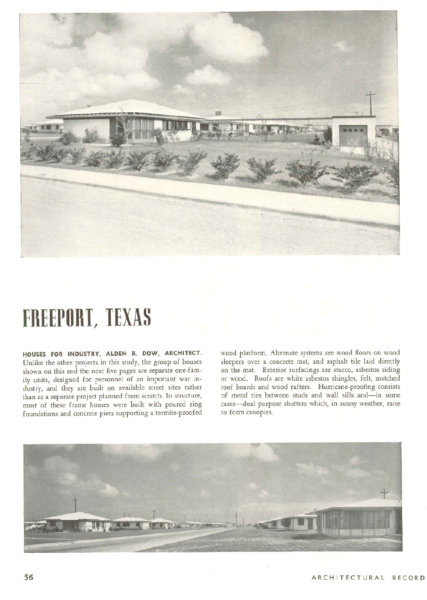

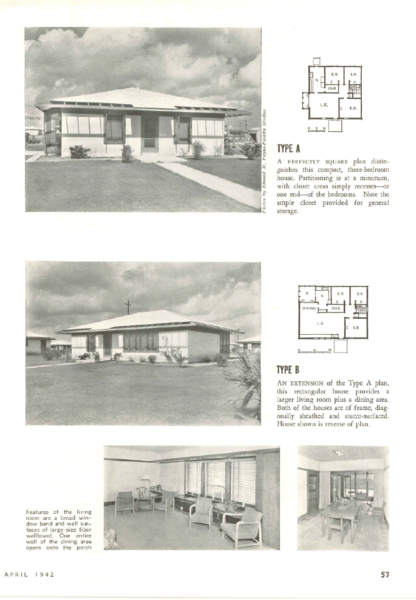

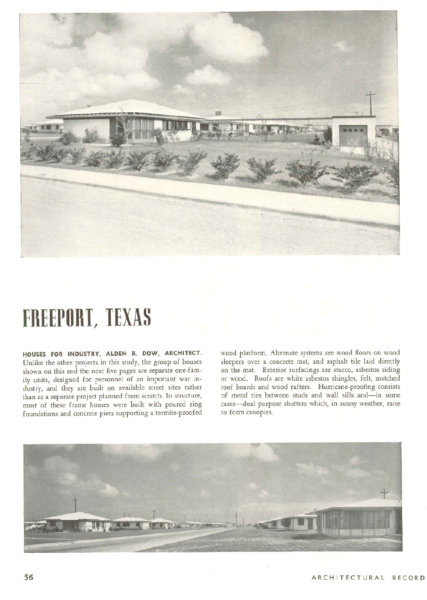

Following Pearl Harbor, the coverage of Dow’s own work in the architectural press became inextricably tied to the intertwined problems of wartime building, modern public housing, and postwar planning. The implications of this conceptual nexus for modern architects like Dow were perhaps best exemplified by MoMA’s “Wartime Housing” exhibition, which opened in April of 1942 (figs. 31 and 32).37 The same month, Dow’s various open-plan homes in Freeport, Texas, built for Dow managers at the new magnesium plant, appeared in a section of Architectural Record titled “War Needs … Housing” (figs. 33 and 34). The issue also included Dorothy Rosenman’s essay “Housing to Speed Production,” an exhortation to publicly-financed modern defense housing as an essential piece of war building and a sharp critique of the manifest limitations of private capital to meet this need: “The old pattern of the speculative, wholesale development of houses-for-sale as an alternative for construction of adequate rental units should have no place in our thinking.”38 So-called “responsible capital will need to invest—not speculate—in a long-term program.”39

The pressure of this national professional climate on Dow’s career intensified the following month. In May of 1942, the Architectural Record again spotlighted Dow’s Texas work—this time his Freeport Hotel—but also, a few pages later, “In the Housing Picture,” a section reprinting part of speech by John Blandford, head of the National Housing Authority, also delivered at the MoMA “Wartime Housing” preview. More significantly, in the same month, but now in the journal Pencil Points, the scope of Dow’s architectural career to date received its first substantial assessment by Talbot Hamlin, a leading architectural critic and proponent of midcentury modernism.40 In framing the issue’s contents, the journal editors lead with Albert Meyer’s “penetrating critical discussion of wartime housing” before introducing Dow and Hamlin’s feature.41 The “largest job” of Dow’s recently incorporated firm, Alden Dow, Inc., is “a new town on the Gulf Coast in the vicinity of a great industrial expansion.” The Lake Jackson townsite is “in the heart of a forest of oak and pecan trees and it is being thoughtfully developed to become a beautiful showplace” (ITI 10).

The editors chose to include here some of Dow’s comments on his work. Their tenor is in keeping with the period’s broader professional emphasis on the architect’s wartime social utility and pragmatic, quasi-scientific value, and they dovetail with Pencil Points’s own editorial rebranding in same issue.42 Architects, Dow urges, “need to create a theory that the public can understand: in other words, a common language” (ITI 10). He narrated his own search for that idiom as a quasi-Oedipal struggle with his chemist father’s skepticism about the professional status of architecture.43 For Dow, this was based on his father’s basic misunderstanding of the job, one shared by many of his fellow artists. Reproaching these “architects, painters, sculptors, and composers [who] prefer to have us believe their creations are carelessly plucked from the clouds,” Dow argued instead for the professional value of “reason”—reason as “the only basis for growth and the only constructive basis for salesmanship” (ITI 12). For readers who felt his comments reflected the “attitude of a cold scientist and not of an artist,” Dow offered a three-stage theory of architectural expression that brokered a compromise between what would later be called “the two cultures” (ITI 12). Architecture starts as a “necessity, is refined as art, and organized as a science,” becoming again an art in its scientific stage (ITI 12). These scientific, rational foundations of architecture entailed a basic rethinking of the nature of professional work—which must, after all, be sold to clients and the public—and indeed demanded media of representation. “When we accept this fact,” Dow concluded, “then the great job for our profession will be to record the reasoning processes at work and to organize them into a science of architecture” (ITI 12).

III.

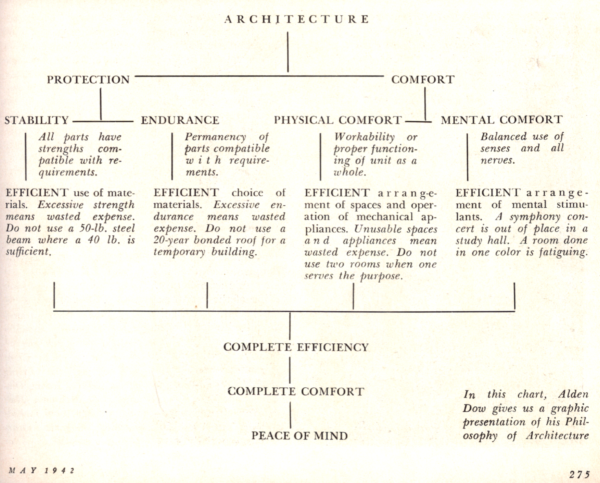

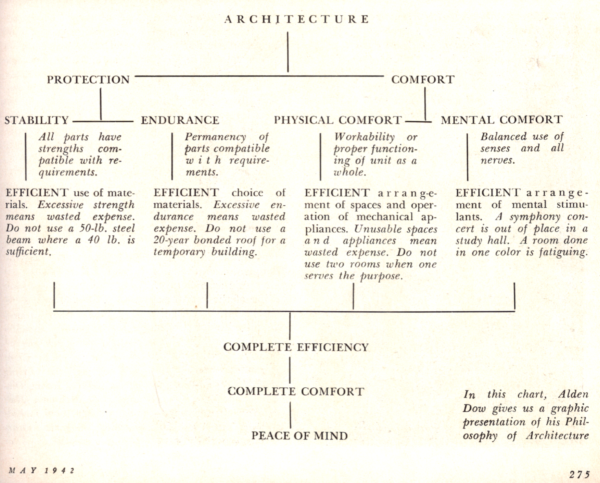

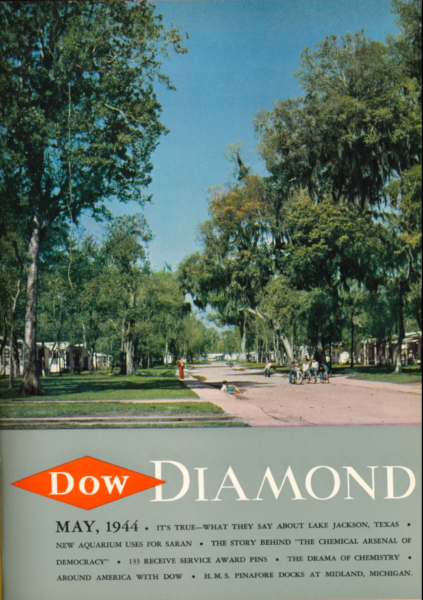

Like many of his professional peers in the early 1940s then coming to terms with the necessity of public relations, Dow was thinking hard about the media of representation best suited to the nature, art, and science of architectural activity.44 The Pencil Points issue clarified that architectural mediation involved both the recording or documentation of reasoning processes and their scientific organization; in Hamlin’s profile of Dow, this included architectural photography and Dow’s attempt at another visual mode of reason: a “graphic presentation of his Philosophy of Architecture” (fig. 35).45 “Planning,” of course, was also a process subject to orchestrated representation and architectural mediation. We can better understand the representational strategies of a planning and development film like Freeport-Lake Jackson (c. 1940–44) by comparing its aesthetics and image repertoire with a few adjacent efforts in architectural mediation in professional contexts that bore directly on Dow’s town planning and his conception of organic growth. One, a 1943 special issue of the journal Architecture and Design on Alden Dow’s work, indicates how Dow understood the philosophical connections between his Lake Jackson adventure in low-cost “housing” and his concept of “the home” as a space of individual growth and cultivation. The other, a 1944 feature on Lake Jackson in Dow Chemical’s glossy PR magazine Dow Diamond, allows us to assess the differences between the corporation’s myth-making rhetoric of Gulf Coast development and the more ambivalent account provided in Dow’s film.46 All, in their fashion, are what Dow might call visual “records” of reasoning processes essential to architecture as an organized science.

First, 16mm filmmaking, 194X. Shot silent and in color, and running just over an hour, Freeport-Lake Jackson streams online today through the Texas Archive of the Moving Image.47 The TAMI website’s keyword tags indicate something of the Gulf Coast ecology that Dow’s footage navigates and a few of the processes it seeks to organize: ferry, sawfish, hurricane, flower, construction, construction equipment, clearing land, family, dredge, brush, bush, African American, barbeque, school, fishing, parade, snake, living facilities, housing, award, cowboy, rodeo. The film’s opening five minutes give us a sense of Dow’s visual reasoning. Loosely edited, the film begins with an insert of a 1940 banner headline from the Freeport Facts announcing the founding act of land acquisition kick-starting Dow’s Texas venture: “DOW CHEMICAL CO. WILL PURCHASE 800-ACRE SITE ON FREEPORT HARBOR.” Fade to black, and then fade in on a road sign reading “FREEPORT CITY LIMIT ELEVATION 16 FT.” These establishing shots introduce a montage of the port city of Freeport and neighboring Velasco (quickly paced shots of architecture, city streets, docks). Dow’s camera observes a small ferry transporting a truck across the river, then cuts to a shot of a large sawfish beached on the riverbank. A smiling man with a knife cuts a large square of flesh from the fish’s side and displays it—both for the child nearby and the camera. Perhaps intended as a bit of local color, of vigorous life on the harbor, the brief episode, if not a micro-parable of extraction, conveys a way of feeling about resources and about non-human nature’s readiness-to-hand for human agency and technique. Like the truck or the ferry that gets it across the river, the knife is small tool and a technology in a film whose mise-en-scène teems with technics at all scales (figs. 36, 37, and 38). Dow’s composition everywhere underscores the collaboration between technical forms and human practices that constitute the process that German media theorist Bernhard Siegert refers to as “hominization.”48

The editing pattern gives us something of the topographical texture of Dow’s new plant site, a harbor town, and the sequence now announces the arrival of Dow Chemical’s representatives into that scene. A long shot captures five men, alongside their surveying equipment (fig. 39). After a brief cut-in to three men arranged around surveyor’s tripod, we return to a montage of Freeport city streets. Now, though, Dow composes a long shot of a white church (fig. 40) and then a larger two-story building, both carefully framed to be seen through and under windblown branches in the mode of the picturesque. Unlike the images seen thus far, none of which are conventionally beautiful, these shots introduce a lovely brief sequence of flowering bushes, close-ups of colorful flowers in bloom, rows of pruned trees neatly planted between sidewalk and street; these images are bookended by a shot of a row of bungalows with roofs framed by overhanging leaves of trees above (figs. 41, 42, 43, 44, and 45).

This, Dow’s development film reasons, is Freeport’s built environment before or beyond the new plant, but also an already-cultivated, semi-developed Freeport continuous with the plant, seemingly made for it. We will shortly get our first view of the construction process underway at the new plant in the film’s next segment, including shots that concentrate our attention on the human laborers (fig. 46), others on the operations of their heavy machinery, and still more on the vast assemblage of technology and techniques, people and things, human and mechanical agencies, that together bring this new magnesium plant into being (figs. 47, 48, 49, and 50). It is typical of Dow’s editing to assemble architecture, nature, and human technics at various scales in this way. There is no inaugural act of groundbreaking on the new plant. Instead, the techniques of Dow’s land surveyors are represented within a long-established developmental process of the human cultivation of nature. Seen in this light, the activity of land surveyors is much like that of gardeners or of landscape architects, only working at different scales and within an ecology that includes their actions and whose value is enhanced by their agency. Dow’s own film camera doubles this work of reconnaissance and surveying, looking at the acts of surveying and inspection with his own eye—the eye of a developer, after all (fig. 51).

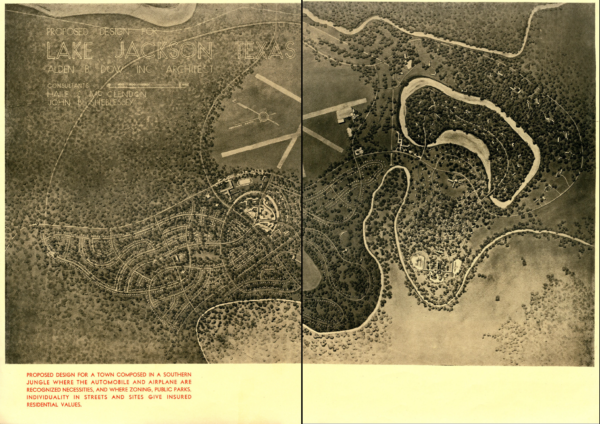

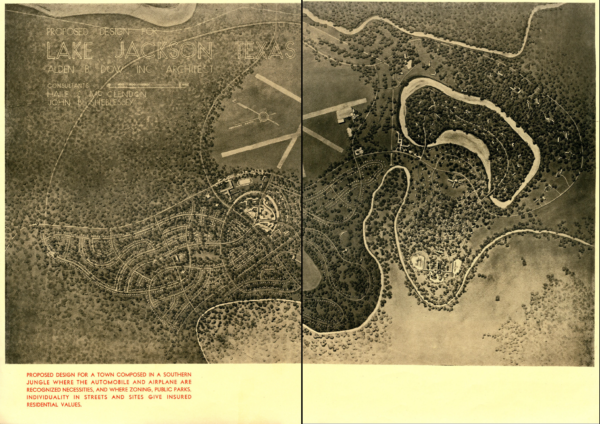

This tendency to ensconce new processes of building within the continuity of natural landscapes is given quasi-theoretical explication in Dow’s Architecture and Design special issue. The issue opens in the planner’s mode of visual abstraction.49 A note before the photography credits explains that “the photographs displayed in this publication don’t represent any particular community. They are examples of this Architect’s work, constructed in various parts of the country.”50 This claim to the abstract typicality or non-locality of Dow’s labor is endorsed but also challenged in the issue’s first images—Dow’s “proposed design” for the Lake Jackson townsite, rendered via aerial photography of the site (fig. 52). The caption beneath the photo explains that the town design for a petrochemical-industry serving autopia was “composed in a southern jungle where the automobile and airplane are recognized necessities, and where zoning, public parks, individuality in street and sites give insured residential values.”51

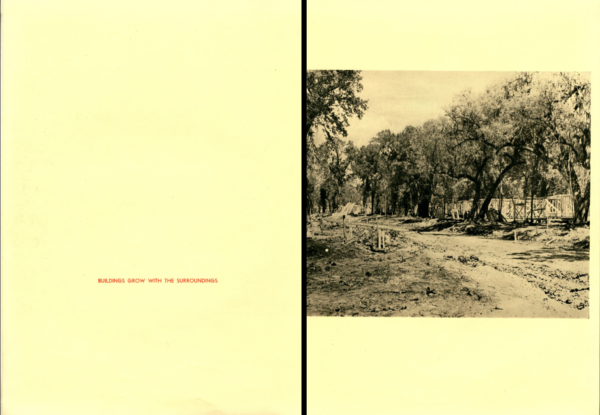

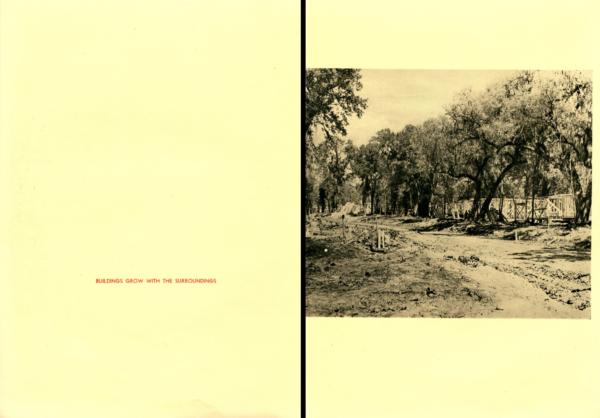

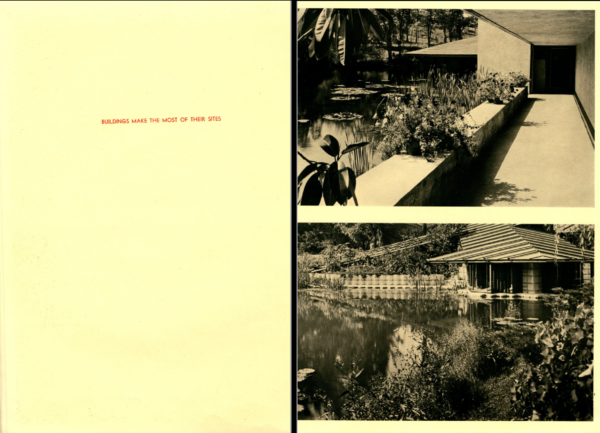

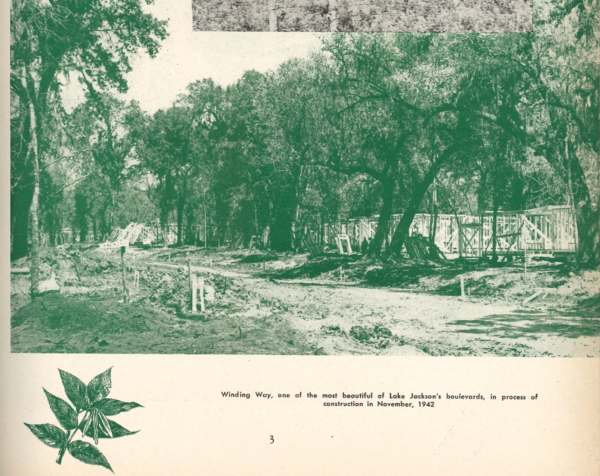

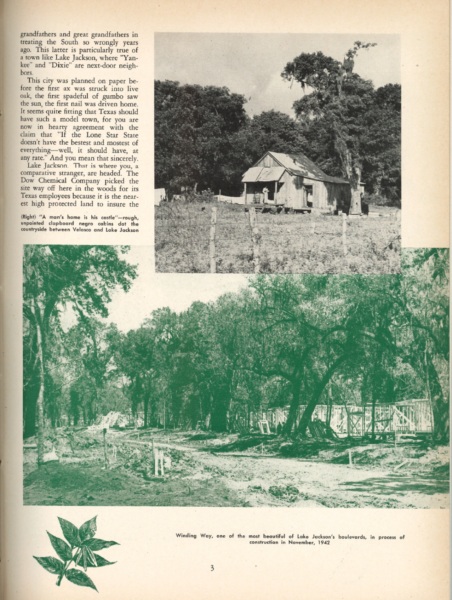

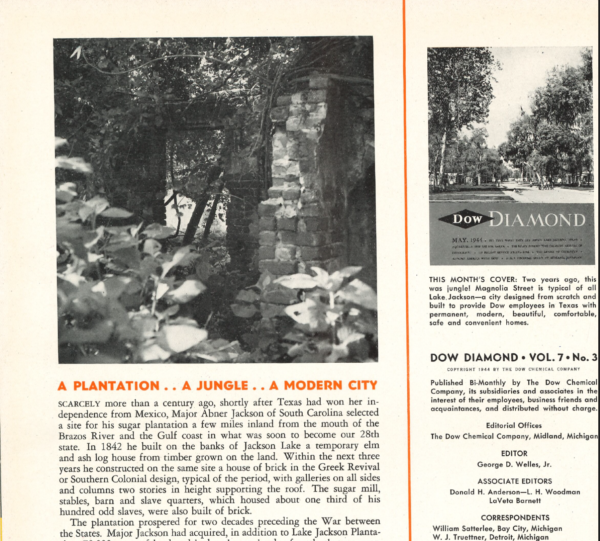

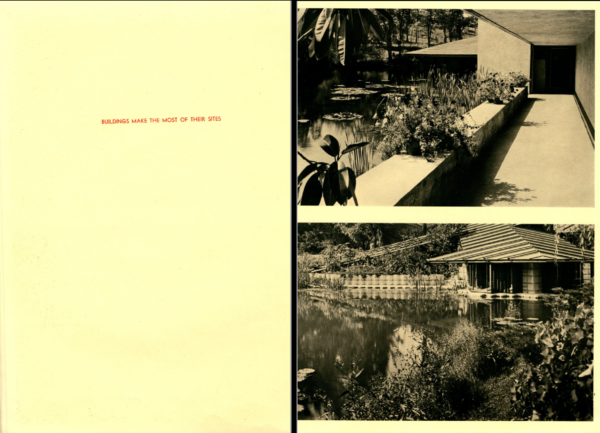

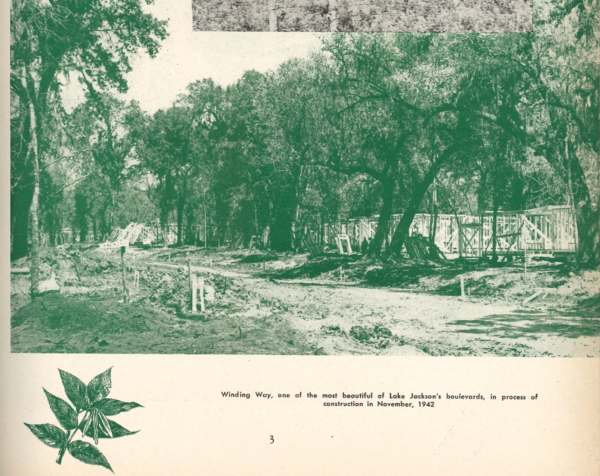

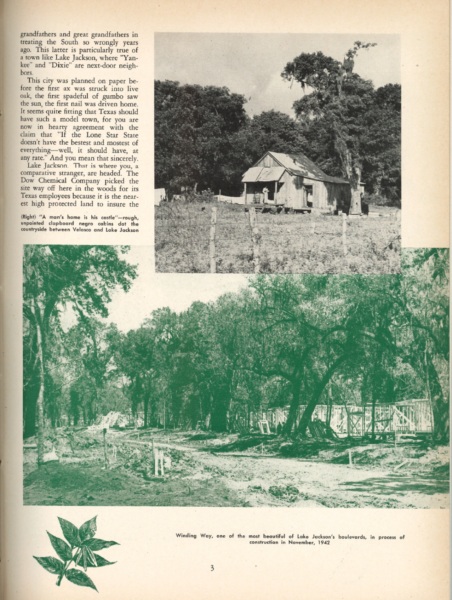

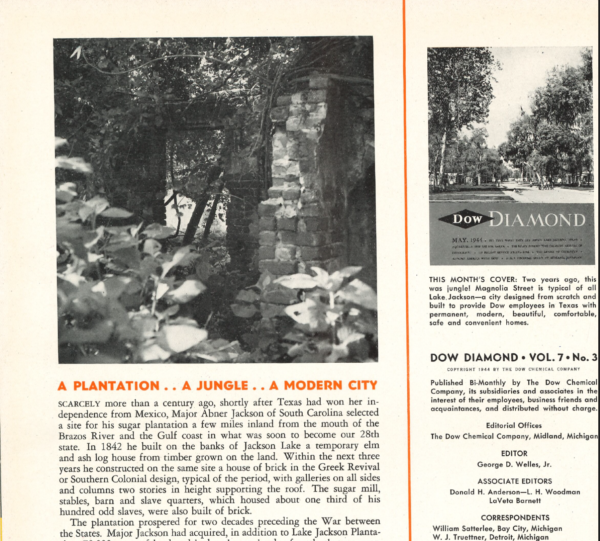

This planning image, stretching across two pages, introduces a visual pattern in the issue’s layout that will oscillate between the architectural photographs of Dow’s work and brief, koan-like design principles. Their modernist simplicity and rhetorical self-evidence are emphasized by their centered composure on the page in red sans-serif typeface that picks up the color of Dow’s own logo. The first two of these declarations, “BUILDINGS GROW WITH THE SURROUNDINGS” and “BUILDINGS MAKE THE MOST OF THEIR SITES,” provide visual and philosophical continuity between the Texas project and Dow’s domestic work, interleaved between photographs of “housing” and “home” (figs. 53, 54, and 55). The first depicts several wood-framed houses under construction, snuggled among the trunks of giant oaks. Uncaptioned, this is a photo of some of Dow’s low-cost Lake Jackson homes, taken by November of 1942. The road under construction and soon to be paved is “Winding Way,” one of the gently curving boulevards through the former swamp and named by Dow that were a signature feature of his town planning, guaranteeing the “individuality” of street-facing private lots with no two plots exactly alike. We know this because these same photographs of developmental process circulated in various publications, including in Dow Diamond’s coverage of the completed townsite the following May (fig. 56).52 There, the image is captioned and printed in green, but the future home’s colorful modernity is laid out in contrast to another kind of home—a local cabin—and another time: “A man’s home is his castle—rough, unpainted clapboard negro cabins dot the countryside between Velasco and Lake Jackson” (fig. 57) (LJ 3).

The Dow Diamond piece, penned by the magazine’s editor in a quasi-ethnographic second person, greets the reader as a “comparative stranger,” to be acclimated to Alden Dow’s surprising new town, “planned on paper before the first ax was struck on live oak, the first spadeful of gumbo saw the sun, the first nail was driven home” (LJ 3). As such, this other way of life figured by the “negro cabin,” which pre-exists Dow’s development and is also historically superseded by it, is only briefly acknowledged: “One room, shaded by huge trees, their occupants with some bright colors about them.” These cabins appear so as to disappear—scenery to be passed through en route to Lake Jackson’s modernity, with its model homes “altogether modern in appearance and workability” (LJ 5, 8). But the cabin’s appearance is also structurally necessary to the deep logic of the article’s animating boosterism. It indexes longer histories of race, war, labor, and white supremacy in the U.S., giving some texture to the article’s folksy, corn-laden tone, which flirts with plantation romance as it offers a tongue-in-cheek voyage through a “romantic Deep South, as it used to be, before Yankee aggressiveness and Southern hospitality joined forces in our fight against a common enemy” (LJ 1). As a work of corporate PR, part of the article’s gambit is to perform the carpetbagging Dow Chemical Co.’s own at-home-ness in the South. It seeks to give its reader access to a similar familiarity with location, an inside scoop. Thus the ingratiating bad jokes about “Yankee aggressiveness” and the author’s unfortunate lapses into dialect.

Taken together, these two records of Dow’s development offer different ways of understanding Lake Jackson’s growth processes. One, Dow’s self-representation in Architecture and Design, is set in the key of organic architecture as an example of harmony between building and site, technics and nature, each growing continuously with the other. Seen in this light, the temporalities of the freshly built functional house and the towering oaks above, draped with Spanish moss, are somehow one. The other, from Dow Diamond, racializes and mythologizes Dow’s “modern town carved from a jungle,” surfacing in the process a familiar, settler-colonial model of land development and progress (figs. 58 and 59). Read this way, the article’s insistence on the town’s youth (“more children per block than you have ever seen in your life!”) or its exhortation that “you notice where the children are playing—clean white homes trimmed in bright colors” are heard as coded endorsements of the sheer fecundity of Lake Jackson’s newborn, state-funded whiteness (LJ 8).

Other moments are less subtle. Describing the FHPA’s management of the government-run duplexes and the renting and selling of privately built houses, the author notes, reassuringly: “You’ll find that there are no indigenous people (bums) in the city. Everybody has a self-sustaining job so there will be no taxes for the needy, and no slums. All areas are restricted in the deeds and these restrictions will run for 25 years and continue thereafter unless the majority of voters brings this question up” (LJ 11). The planned public-private partnership has yielded an exuberantly modern town devoid of indigeneity. Its “residential values” are insured by the quality of Dow’s houses, whose fifty-plus designs “have individuality and color” and an emphatically exclusive vision of “housing” that is all white.53 Lake Jackson, after all, was a racially segregated community until 1964. Most Black citizens in the area lived in Freeport.

How does this rhetorical repertoire of photographic images in these contemporaneous records help illuminate the developmental eye of Dow’s silent film? Most obviously, freeing static images meant to signal growth patterns into motion, the film exemplifies “the process genre” in its demonstration of the architect’s career-long fascination with technical processes.54 Intertwining and overlapping creative processes at various scales, from the industrial or the geopolitical to the communal and domestic, the film is centrally about the conceptual processes of planning and speculation that achieved new national visibility during the war. These processes included the construction of Dow Chemical’s new magnesium-processing plants with their vanguard extractive operations and the conceptual technique of town planning, but also of the laborious old technique of clearing the swamp, performed mostly by Black and Brown workers who could not live in the modern town they helped to build.

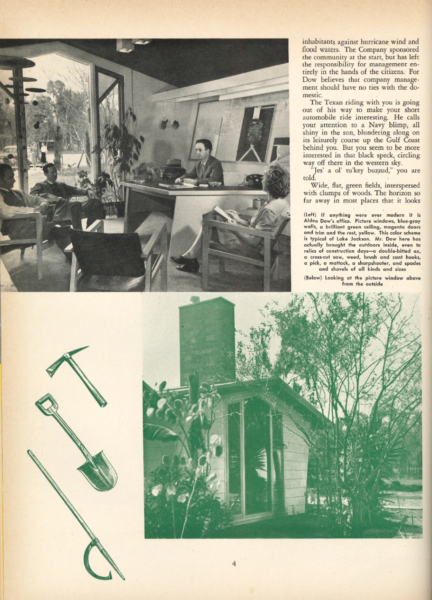

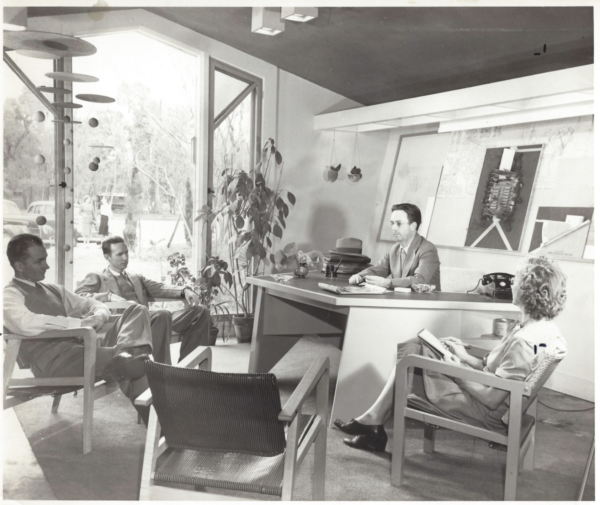

How did Alden Dow understand this labor? What is its aesthetics? As is clear in his careful use of architectural photography to represent his own work, Dow was keen to find a proper aesthetic form for labor. He understood his own conceptual activity alongside various processes and scales of human cultivation. The Dow Diamond article, for example, observes how Dow’s uber-modern Lake Jackson office does the work of “bringing the outdoors inside” not just through its “large picture windows” but quite literally by displaying older “relics of construction days—a double-bitted ax, a cross-cut saw … spaces and shovels of all kinds and sizes” (fig. 60) (TPG 4). Dow’s modern office, and its mise-en-scène of white-collar work, doubles as a kind of museum of labor history, as old tools and technics fall out of history to assume a decorative function alongside mobiles and low-slung chairs in the colorful command center of Dow’s planning enterprise (figs. 61 and 62).

The Freeport-Lake Jackson film exemplifies a particular kind of midcentury “material consciousness” in Dow’s work, and this is most obvious in the film’s many returns to the scenes of the heavy labor of forest clearing, dredging, and road building (TPG 38). Generally speaking, the film moves from acts of surveying and construction to scenes of daily life in the upstart town; processes of building this new environment give way to shots that texture the look of the postwar good life as it was augured by the Lake Jackson example: women tend to their backyard victory gardens; a young couple enjoy private conversation in front of Dow’s office or outside the school; children parade gaily, seemingly without end, through the recently laid roads. But Dow is also at pains to observe the scale, magnitude, technical skill, and sheer physical drudgery of the labor of clearing the townsite (figs. 63, 64, 65, and 66). These recurring images stall a progressive, strictly chronological narrative that would easily harmonize building and site, naturalizing them as part of the same organic growth process. If Dow Diamond sold that narrative of Lake Jackson’s transformation with headlines like “A Plantation … A Jungle … A Modern City,” Freeport-Lake Jackson inhabits and magnifies those ellipses, lingering in the intertwined material processes that constitute the temporal intervals between these finished states. Those intervals are the spaces of historicity and historical recurrence, especially in the way the site’s plantation history of slave labor (also romanticized in Dow Diamond) returns in the racialized low-wage work and small-scale technics that produce this “modern city” in a new phase of plantation modernity.55

One sequence featuring these laborers compels special attention. It conjures the sheer power and historical instability of profilmic reality, underscoring what Siegfried Kracauer famously described as film’s material contingency. The small unit of everyday life revealed here is what the TAMI keyword tags as “barbeque,” specifically an outdoor barbeque, or rather barbeques, plural. The sequence begins with shots of the workers alongside a stretch of recently laid concrete road and images showing them preparing the road surface and laying the sewer and water lines underground. We cut to an informal barbeque in the woods, an apparent work break. A group of Black laborers surround a table framed in long shot. Their faces are obscured, but their gaze is directed at Dow’s camera. A rapidly edited series of shots intercuts their (apparently supervised) meal and another, more formal all-white outdoor barbeque. The precise spatial relationship between these locations is rather unclear, but they are clearly segregated, de facto. We then see Dow observe their apparent coming together, as a Black man, standing alone on the flatbed of a red pickup truck, hands folded in front of him, appears to address the camera, and an audience of white barbeque attendees. Dow reframes the shot to show other Black laborers in a group adjacent to the man in the truck. A cut repositions the standing man in center frame, and then we get a shot of the white barbeque, framed by a Black cook in a white apron, working a large grill. The footage of the Lake Jackson good life continues with images of white women flipping hot dogs, then shots of women observing a children’s theatrical rehearsal on an outdoor stage. Finally, we return to footage of the laborers in the street before a new sequence of shots of work outside some recently built homes.

What, one wonders, did the man on the red truck say (fig. 67)? Was this an address, a performance, an impromptu speech or prayer, or something else entirely? And what about this moment in the process of building Lake Jackson prompted Dow’s camera to linger on it? Just “a fragmentary moment of visible reality,” per Kracauer, its meaning is unclear. Did Dow mean this to ennoble and humanize the labor that, with his own, brought the town into being by observing workers in a moment of leisure? Or is this a record of labor as aestheticized “local color?” For viewers today, the sequence reads as an uncanny micro-spatial parable of the segregated social life constitutive of the early growth of Dow’s model postwar town. Profilmic contingency marks both the history and future of housing problems and exclusions around the very category of “home.”

On another conceptual level, the notion that buildings “grow with their surroundings” or, to summon another Dow koan, the idea that “gardens never end and buildings never begin,” ask us to understand technics and nature as part of a thicket of growth patterns, intersecting forces, and entangled agencies with no clear or final line demarcating human action from its natural outside. Later in his career, for example, Dow often deployed film as medium to conceptualize creative process. In one now-lost film, for example, apparently made for pedagogical purposes for fellow architects, Dow laid out a theory of creative growth and dynamic form in nature, extending from meteorology (the changing structures of cloud formations) to chemistry and physics (atoms and elements) to botany (the interaction of flowers and insects). He casts these actants, including human agents, as interacting vectors of force shaping organic form and spawning individuality and growth, interest and quality: “Then man comes into the thing, and he introduces a whole new pattern of force … He changes the shape of the ponds, plants shrubbery here and there—all in order to meet a whole system of forces within him.”56

Seen in this light, town planning on the scale of Lake Jackson enacts Dow’s concept of anthropogenic force, naturalizing a developmental process on the Texas Gulf Coast that was deeply historical, as the film can’t help but show. Freeport-Lake Jackson is attuned, as perhaps only the work of this Dow scion could be, to the transformative and contingent relations between labor, instrumentation, and materiality produced by the expansion of the petrochemical industry and the new, postwar infrastructure of daily life augured by this model town. It’s a film about the intertwining of nature and non-nature, property and process—about that specific form of organic creativity called “real estate development.” A telling instance of what J.D. Connor and I have elsewhere called “the fitful sublimation of infrastructure into image by cinematic means,” the film makes visible the infrastructures, forms of labor, and dynamic forces of extraction that are the conditions of possibility of this particular scene of modern postwar democratic living—one Dow saw as exemplary, and a normative ideal.57

The best summation of this ideal, circa 194X, was Dow’s essay “Home and Housing,” his most substantial written reflection on the Lake Jackson project. Dated May 1944, it returns to his three-stage theory of architectural organization as an art and science and his attendant maxims about variety, balance, contrast, and individualism in architectural form and creative activity across media. Now, though, this is framed in the context of a foundational distinction between “home” and “housing” that was sharpened by his Gulf Coast adventure. The essay argues for an abiding dualism across various scales of life and living. “On the one side there is discipline, or duty,” represented in society by “industry,” which is “not only the factory or plant: It is the office, the kitchen, the farm, the classroom.” On the other side is “home,” the “side of freedom and ideals.”58 These two sides are not, ideally, in contradiction or conflict but mutually constitutive and capable of dialectical resolution: each supports the other and feeds the other’s growth: “Industry is the practical provider. Home is the relaxer” (HAH 1). Lake Jackson, the product of his last three years of work, is summoned as a model organic unity of home and industry. Michigan, he continues, could stand to learn a basic lesson from Texas: “housing is not enough.” “One of the greatest industrial states of our country,” Michigan has forgotten the need of “that relaxer, the home” (HAH 2). Instead, “under the stress of the times, we have constructed vast housing projects, which provide the most modern shelter for thousands of people. But they provide no means of individual expression” (HAH 2). Without that, when people “fail to find satisfaction in their home life, Michigan’s development will suffer” (HAH 2).59

What emerges here is an account of human development in the incipient postwar period that enshrines the private home as the therapeutic space of individual self-cultivation and creative self-expression and scales this developmental narrative up to the level of community and society.60 The “new architecture,” Dow insists, emerges as a stimulus to human inventiveness, imagination, and personal growth (HAH 6). A home’s capacity to provide ways for humans to “grow both physically and mentally” differentiates it, as a home, from mere animal shelter or “housing” (HAH 5). Where is the public and the social in this account? Pride in home-ownership, Dow argues, generates pride in belonging to larger scales of social life: “Our people should have the opportunity to develop, to develop themselves and their homes. This pride will both lead into and spring from a pride and faith in their home and country” (HAH 3). Conversely, attractive, well-maintained public spaces work in the mode of what behavioral economics might call an aesthetic “nudge” in the built environment: “when our public areas are well-tended and blossom with flowers, we are inspired to further effort in our own gardens” (HAH 5). This is the bourgeois ecology of property-value maintenance. Neighbors, Dow insists, are crucially important to the “formation of a happy community” (HAH 4). Yet mindfulness of or tolerance for aesthetic differences with one’s neighbor aren’t finally enough to secure individual freedom and defend against lapses of bad taste, ugliness, or plain rudeness: “This is the reason certain restrictions are essential to a happy community” (HAH 4).

One also hears in the essay’s articulation of an architecture of individualism a politically charged hostility to “mass form” of all kinds as cultural techniques of development and growth (HAH 6). Such forms included “organized play and various kinds of clubs” or forms of “pacifying” mass media (he names the radio and moving pictures) or “organized, regimented forms of housing” (HAH 6). Indeed, Dow will explain the current demographic movement from mass housing to “less comfortable and convenient, often more expensive shelters in suburban and rural areas” as an expression of a natural instinct for a home, where “the individual wants to reign supreme” (HAH 6). In 1944, near the end of a catastrophic global conflict that proved decisive to his own creative expression, the essay scales up its analysis from happy home to happy community to a happy society by psychologizing a basic “creative urge” whose expression “can follow either a constructive or a destructive channel” (HAH 7). When constructive expression is blocked, the “universal creative urge will seek a destructive outlet”—as in the behavior in “thwarted children,” grown-ups, and even in “whole societies, as we see today in a world at war” (HAH 7).

However unsatisfactory “Home and Housing” may be as a theory of history or as an explanation for the confluence of historical determinants that brought Lake Jackson into being, including the sheer war-fueled force of capitalist growth and extraction as entwined processes of what was dubbed “creative destruction” around the same time, Dow’s essay is itself a useful historical artifact.61 It helps us understand the terms through which Freeport-Lake Jackson circulated in the service of civic boosterism over the years as it screened for citizens, town leaders, and Dow employees at public festivities celebrating the tenth and then twentieth anniversary of the town.62 For his town’s tenth birthday, Dow extolled Lake Jackson’s unique “awareness of design,” marked by “qualities” rarely found in the U.S. and “only in small neighborhood areas”: “It is this quality that produces [a] variety of streets, building sites, and buildings,” that allows “one building to live harmoniously with another,” that “makes your children the best kind of citizens.”63

Quality, harmonious living, design for the “best kind of citizens,” a rejection of organized mass housing. On the cusp of the postwar and incipient white flight and suburbanization, also fueled by racist federal housing policies, one can’t help but hear in this conceptualization of home the constitutive exclusions of Dow’s normative ideal of human freedom and flourishing. Indeed, as Dow kept tabs on his Lake Jackson assets through the 1950s (he continued to own property there until the late 1950s) and consulted with civic leaders on Lake Jackson “values” and “quality,” circulating his development film in the process, he resisted efforts to racially integrate the town. In December of 1947, for example, Dow’s colleague R.J. Pfeiffer, wrote to Beutel to express Dow’s opposition to a proposed “Colored Housing Section” at Lake Jackson, and quoted Dow:

I don’t think Area J should be considered for this purpose. In fact, I think they should be very slow in establishing a colored section for they have it now in the Clute area. Colored sections today are never anything to be proud of, and are always a sore spot in every town. I believe, if given time, this situation will improve. The section now adjoining Area J, and owned by colored people, I believe will naturally become a colored section. I recommend encouraging this rather than developing a new one.64

Just as Dow’s many celebrations of home-ownership used the boosterist rhetoric of the contemporaneous real-estate industry and the FHA, who actively promoted private home-ownership as a civic and moral virtue, Dow’s reservations about a “colored section” of Lake Jackson echo persistent rationales for racial exclusion among white homeowners anxious about their property values. In moments like this, Dow’s commitment to aesthetic quality, neighborliness, and the importance of thoughtful deed restrictions to ensure a happy community of amortized single-family homeowners reminds us that “federal promotion of homeownership” in the 1940s “became inseparable from a policy of racial segregation.”65 Note how Dow’s idiom of organic growth patterns surfaces here to explain racial separation—the area that currently has a few Black homeowners “will naturally become a colored section,” a process that can be encouraged. A similar logic undergirded the PWA’s and USHA’s policies in segregated public housing in the 1940s, as Richard Rothsthein has argued.

In fact, direct references to the racially charged debates about public housing in Michigan are noticeably absent from Dow’s account in “Home and Housing.” For a Detroit audience in 1944, Dow’s critiques of mass housing in Michigan and his defense of the therapeutic value of the single-family home as a hedge against “destructive outlets” would likely have been heard as a comment on highly publicized struggles for Black public housing in Detroit. These stemmed from the city’s attempts to solve its own wartime housing crisis for its Black war workers, contemporaneous with Dow Chemical’s own urgent housing efforts in Texas. In Detroit, this led the FWA and the Detroit Housing Commission to allocate 200 FHA units to Black war workers and then to the development of the all-Black Sojourner Truth Housing Project, planned for construction in largely Polish neighborhood in the city’s northeast. That project, backed by the NAACP, met with significant resistance from white residents, realtors, and local right-wing demagogues and fascist groups and became a national lightning rod around the explosive racial politics of public housing. In February of 1942, the initial arrival of the new Black tenants at Sojourner Truth sparked two months of violent rioting; a photo-essay in Life magazine that June proclaimed, “Detroit is Dynamite.”66 The upheaval was the prelude of an even more destructive race riot a year later, in June of 1943, which resulted in thirty-four deaths and 635 injuries. Despite continued protests from the NAACP and the UAW, Detroit’s housing projects remain segregated throughout the war.

The basic developmental lesson that Dow hoped to import from his wartime work in Texas back to Michigan—that housing alone is not enough—looks a bit more ambivalent in this context. His paean to the single-family home, cradle of the creative individual, as the postwar answer to the depredations of regimented mass-housing projects, themselves constructed as a response to the “stress of the times,” drastically underestimates the systemic barriers to access for this ideal, obvious as they may have been to many non-white citizens of Dow’s home state. To be fair, Dow explored means of expanding access to home-ownership at various points in his career, and beyond Lake Jackson, beginning in the 1930s with his first experiment in low-cost housing, the Lewis house. To help solve a Depression-era housing crisis for Dow workers in Midland, he designed a three-bedroom “functional house” as one of the Dow Houses the firm built to be rented at reduced rates to its employees. Most telling, perhaps, was his experimental solution to this crisis, the “Home with a Future” (1938), a design that unfolded in three-stages, growing with the income of its owner. Dow explained the design as part of the larger problem of governmental and industrial “paternalism.”67 The problem was that workers were too happy with their affordable, rentable homes—the fact that they wished to continue the benefits of Dow-Chemical subsidized housing, rather than use it as designed: to solve a temporary housing crisis, to save, and then to build on their own. Dow’s plan appears quintessentially sensible—build the home you need and can afford now, expand it later with your growing income. It’s the kind of sober approach to sustainable growth, Dow continues, behind the success of Dow Chemical itself: “The Home with a Future should be like the Company with a Future, like our own company,—a bold start, and the rest—‘for tomorrow.’”68

This logic, the proverbial hand up rather than hand out, is meant as a prudent hedge against financial risk. However detached from the structural obstacles to home ownership it might seem today, it affirms a more basic truth—that the home, as Jonathan Massey has argued, is among other things “an instrument for distributing economic risk and opportunity among individuals and institutions.”69 Dow’s town-planning experiment in Texas, and his development film, Freeport-Lake Jackson, offer contemporary scholars a window into the unevenness of this distribution at the dawn of the postwar. For Dow Chemical, the wartime wager on Gulf Coast real estate and the expansion of its extractive operations in magnesium and styrene paid off handsomely, laying the groundwork for its explosive corporate growth. In 1947, buoyed by the successes of its geographic proximity to petrochemical feedstocks in and around Freeport and Velasco, Dow built a new plant and formed the Brazos Oil & Gas Co., “a wholly-owned subsidiary with 250,000 acres of oil and gas leases in Texas and California,” to power its plant growth and enable petrochemical innovation through expanded pipelines for ethylene, natural gas, brine, and liquefied petroleum gases.70 By 1952, an admiring feature in Fortune, “The Dow Expansion,” would hail the company for “one of the most spectacular rises in postwar chemicals,” with its eleven-fold growth in both plant capacity and sales far outpacing the strong numbers of the industry as a whole (DOP 104). The growth was especially notable in plastics, “which has come up since the war from practically nothing to account for over a quarter of total sales” (DOP 178).