I.

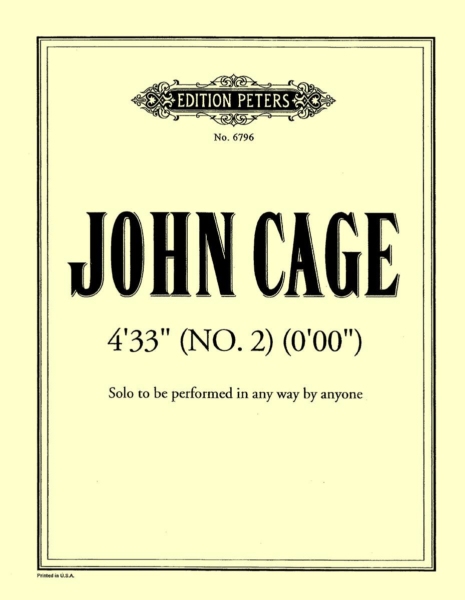

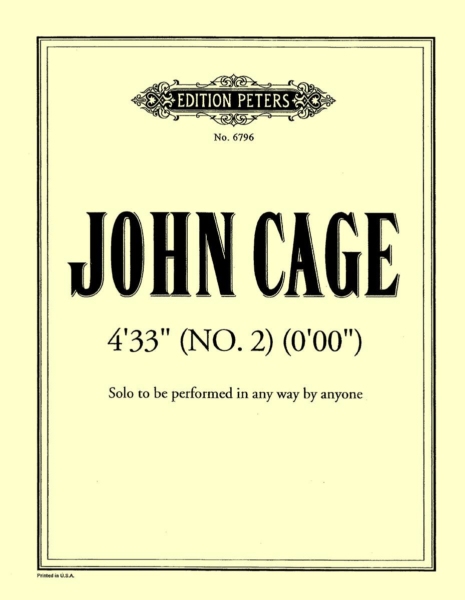

In 1954, John Cage gave a talk entitled “45’ for a Speaker.”1 According to its preface, the text was composed using bits taken from previously written lectures, new material, and scripted noises and gestures such as snoring and blowing his nose, the timing of which was determined by aleatory operations. For the new material, Cage made a list of 32 subjects, and when the coin-toss dictated, he wrote a passage on that topic. Among subjects such as structure, time, sound, silence, chance, theater, non-dualism, listening as ignorance, and asymmetry of probability, one finds the rubric “error.” And so, within this wide-ranging statement of his aesthetics are to be found scattered reflections on error. For example: “The thing to do is to keep the head alert but empty. Things come to pass, arising and disappearing. There can then be no consideration of error. Things are always going wrong” (S, 187). The category of error belongs to an aesthetic approach that Cage refuses; for him, all sounds are welcome in the composition. These ideas should be understood in the context of his use of aleatory (randomizing) techniques in the compositional process—such as tossing coins, crumpling paper and placing notes in the intersections of the folds, and using paper imperfections and star charts to determine the score—as well as his practices of allowing the performers a large freedom of interpretation and inviting the contingencies of the environment to contribute to the work. Perhaps his most open work is the 1962 event-score 0’00” (4’33” No. 2), whose full score consists in the sentence: “In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action.” (Fig. 1) In adopting aleatory methods and incorporating environmental contingency, he rejects the compositional paradigm according to which there can be errors. An error, in the context of creative work, may be defined as an action that is done contrary to the actor’s intention. The idea of error only makes sense when there is an intention, when a creator’s head is not “empty”: the empty head in the above quote is not only that of the audience but that of the composer, who shouldn’t make decisions but simply allow things to come to pass, arise and disappear. Because the composer doesn’t control the events, “things are always going wrong.” This is one of Cage’s paradoxical punchlines, as he has switched points of view; from the point of view of the intentionalist, such uncontrolled events are considered as “always going wrong.” For Cage, there can be no errors or failures in his musical composition and production since all possible outcomes of the process are equally valid. As he refuses the category of the “rightness” of any element of aesthetic production, whether that “rightness” is understood as subjective or as participating in a formal compositional system, it is logical to refuse that of “error” as well. “No error. And no wondering about what’s next” (S, 192).

Cage’s refusal of the possibility of error should be taken in the context of those musical practices he was actively rejecting at the time: European traditional and avant-garde composition, based in either traditional harmony or atonal counterpoint, in both of which the idea of error was a reality, though not necessarily a hard and fast one. In traditional tonal harmony, every dissonance must be justified by a subsequent resolution, and if it isn’t, this is considered a wrong note or an error. And in the 1950s atonal music was no longer in the early liberational phase of Schoenberg’s “emancipation of the dissonance” from the requirement of tonal resolution, but in the codification phase of Boulez’ generalized serialism, wherein if you compose a D where the row demands an E, you’ve made an “error.” In a way, Cage wanted to extend Schoenberg’s emancipation of the dissonance beyond that of half-tones and into the real-world dissonance of noise and environmental sounds. But Cage’s repudiation of the concept of error goes beyond his critique of traditional and avant-garde composition and takes aim at all aesthetics involving intentional control, whether that control is exercised within or outside of a compositional system. “A technique to be useful (skillful, that is) must be such that it fails to control the elements subjected to it” (S, 154), he says, with characteristic paradox. Cage’s desire to efface intentionality from the compositional process is partially due to the influence of Zen Buddhism, but also to the anti-expressivity bent among the mid-century avant-garde. The other composers associated with Darmstadt in the 1950s were seeking to eliminate personality and expressivity through the quasi-mechanistic determinism of generalized serialism; Cage and others in the New York School through aleatory and indeterminate methods. Cage took this anti-expressivity to an extreme by attempting to efface the intentionality and even the agency of the composer entirely, and in so doing became perhaps the clearest theorist of aesthetic anti-intentionalism.

Elsewhere in the same lecture, he writes: “Error is drawing a straight line between anticipation of what should happen and what actually happens. What actually happens is however in a total not linear situation and is responsible generally. Therefore error is fiction, has no reality in fact. Errorless music is written by not giving a thought to cause and effect. Any other kind of music always has mistakes in it” (S, 167-68). Cage turns on its head the intuitive description of aesthetic error as an action that is done contrary to the actor’s intention, and here gives two descriptions in its place. We have already seen one of them in the earlier quote, that for him error is fiction and doesn’t actually exist. The other one equates error with intentionality and control, basically saying that any intentional attempt to control an outcome is erroneous: error is the attempt to create a direct relation between “anticipation of what should happen and what actually happens.” What happens should be unobstructed by the composer’s anticipation, decision-making, planning or intention. Indeed, the party “responsible” for the event is “what actually happens,” not the composer. Similarly, Cage states in another passage, “I will not disturb by my concern the structure of anything that is going to be acting; to act is miracle and needs everything and every me out of the way. An error is simply a failure to adjust immediately from a preconception to an actuality” (S, 170-71). Here the actor is not the composer, but “anything that is going to be acting,” with a metaphysical resonance. The phrase “to act is miracle” is telling: while the verb normally implies a subject, the infinitive form removes the verb from any particular instantiation and the human agent is effaced by the arrival of an uncontrolled and anonymous “miracle.” Cage considers an act to be an event, or perhaps, he thinks that an act should be an event. The “failure to adjust immediately from a preconception to an actuality” means the attempt to control the process, to refuse the validity of any unexpected actuality. “A ‘mistake’ is beside the point, for once anything happens it authentically is” (S, 59). In Cage’s aesthetics, the only error is intentionality itself. No intentionality, no error.

Quite logically, Cage relates the impossibility of error on the part of the composer to the impossibility of error or “misunderstanding” on the part of the audience. He states: “I am interested in the fact that [sounds] are there, and not in the will of the composer. A ‘correct’ understanding doesn’t interest me. With a music process, there is no ‘correct understanding’ anywhere. And consequently, no all-pervasive ‘misunderstanding’ either.”2 Although it is indeed difficult to define exactly what a correct understanding of a musical piece might consist in, the question is ultimately no more delicate than the same question regarding painting or literature. Just as the ideas of “rightness” and error participate in an aesthetic approach Cage refuses, so do those of understanding and misunderstanding. Rather than understanding, for him there is only “experience”: “I think the most pointed way to put this distinction is by using the word ‘understanding’ as opposed to ‘experience.’ Many people think that if they are able to understand something they will be able to experience it, but I don’t think that’s true. … I think that we must be prepared for experience not by understanding anything, but rather by becoming open-minded.”3 “[My works are] not objects, and to approach them as objects is to utterly miss the point. They are occasions for experience” (S, 31). It follows that aesthetic experience is particular to the person experiencing, and Cage is quite clear that everyone’s experience of his work is different. “I think each person should listen in his own way, and if there are too many things for him to listen to, and in that complex he then listens to whatever, he will have his own experience, and there will be a strength and validity in that” (CC, 236). In his interviews with Cage, Daniel Charles puts this succinctly: “So it’s also an invitation to plurality or multiplicity. Your experience is one thing, mine is different. The works signed ‘John Cage’ don’t belong to their author. They are just as much what you make of them as what I make of them, because you are there and I am here,” to which Cage responds, “I agree completely” (FTB, 234-35). We would expect, then, that in an aesthetic philosophy based upon experience and the impossibility of error or misunderstanding, the concepts of meaning and truth would be rejected as irrelevant as well. Cage does not use these terms often, but they appear occasionally, precisely in the context of aesthetic “experience.” When in their interviews Daniel Charles remarked that Cage “felt at home” in the philosophy of Wittgenstein, Cage answered: “That’s right. But I didn’t understand everything. I retained this sentence: ‘Something’s meaning is how you use it.’ … Everything we use is legitimate, since we use it. That is a situation of fact. There is no ‘meaning’ beyond this situation of fact. Everything is possible. … Use rather refers to experience.”4 Beyond Cage’s “use” of Wittgenstein, what counts here is his explicit equating of meaning, use and experience. Instead of saying that his works have no meaning, he embraces the definition of a work’s meaning as the audience’s particular experience. Interestingly, when he takes a similar stance on the notion of truth, he associates it with “form”: “Form … is wherever you are and there is no place where it isn’t. Highest truth, that is” (S, 186). The “form” of a work is equivalent to “your” experience, and to truth: meaning = use = experience = form = truth. Cage is consistent in his aesthetic relativism.

Cage is right when he asserts that the idea of error only makes sense within an intentionalist perspective. Playing the note D can only be considered an error if I had intended to play F or some other note instead. Using red paint is a mistake only in the context of having meant to use blue (or any other color but red); otherwise, it’s just the act of using red paint. Likewise, the potential for error or failure is constitutive of intentionality. Walter Benn Michaels, working with Elizabeth Anscombe’s theory of intention, writes: “[Anscombe’s] point is that the intentional structure of the failed act is the same as the intentional structure of the successful one.”5 The question is what it means to say that intentionality itself is an error, and whether it’s possible to get “every me out of the way” and thus renounce aesthetic intentionality. Since error doesn’t exist outside of an intentionalist paradigm, the statement that intentionality is an error is self-contradictory. Intentionality (like red paint) can only be considered an error if I had intended something else; for there to be an error, there must be some intention against which the act is defined as an error. What Cage intends is unintentionality—he intends not to intend—but this constitutive paradox of Cage’s aesthetics is not only a logical contradiction but is impossible to fully put into practice. In what follows I’ll focus on Cage’s effort to abdicate intentionality and argue that he intends not to intend, but fails.

II.

How can we interpret Cage’s refusal of aesthetic intentionality? First of all, despite many statements which state or imply that the artist should somehow keep out of the process, Cage occasionally says explicitly that some intentional action takes place, basically by creating the conditions of possibility for unpredictable results. He desires this action to be minimal, and often conceives of it in terms of “asking questions” to be answered by the aleatory operations. He asks, “Why do they call me a composer, then, if all I do is ask questions?” (S, 48). Asking a question involves as much intention as making a statement, as does the incorporation of the answer into an artwork. “Not abandoning [the artist’s role as a creator], simply changing it from the responsibility of making choices to the responsibility of asking questions.”6 Although he occasionally makes such admissions, in his aesthetic writings and interviews he most often says or implies that he wants to avoid artistic intentionality and agency. The method of asking questions of the random oracle is an attempt to find an answer to his central question, that of how to remove himself as much as possible from the process and “let” the material act on its own, “once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of [life’s] way and lets it act of its own accord” (S, 12; 95). “What if a B flat, as they say, just comes to me? How can I get it to come to me of itself, not just pop up out of my memory, taste, and psychology?” (S, 48). Cage desires to transfer agency to the material, and let the B flat act on its own. “It is clear that ways must be discovered that allow noises and tones to be just noises and tones, not exponents subservient to [a composer’s] imagination” (S, 69). But despite these statements and the aleatory methods used, intentionality has obviously not been eliminated. First and foremost, even before intending to let the B flat act of its own accord, Cage intends to create a work. His techniques allow a greater than average inclusion of uncontrolled elements, but the fundamental creative intention remains the same. Without it, and if he truly did nothing, there would be no work. Cage may not like the term “work” (“All I am doing is directing attention to the sounds of the environment” [FTB, 98]), and we may prefer to replace it with “production,” “performance,” etc., but his productions fulfill the minimal condition of creative works: they would not exist without the artist’s intentional creative action. The sounds of the environment would still exist, but not the elaborate direction of attention to them, in the particular ways that Cage signs.

Rather than acting intentionally in a straightforward way, then, Cage intends to act unintentionally, or that is, he intentionally creates the conditions for a partially unintentional or uncontrolled event.7 He selects the elements that will then be arranged by coin-tossings; he creates the deck and then shuffles it before dealing; he sets up a framework involving time, place, title and audience, and then invites environmental contingencies to become part of the work. Intentionality remains intact, especially at the early stage of the process, even if in the second stage, the creation of an unpredictable result, it is perturbed. This intentionality is located in a moment prior to the traditional one of direct compositional choice: rather than creating a work directly, Cage first intentionally devises a procedure (the application of aleatory or indeterminate methods to x or y material), and then lets that procedure operate without his intervention. The locus of intentionality in his work lies in the invention of the procedure and not in the direct creation of the perceptible form. The creative process thus has two distinct phases for Cage: first the intentional determination of materials, conditions, parameters, frameworks and procedures, and secondly the resulting unpredictable production of a work or event. This two-step process is to be found in both “chance” and “indeterminacy,” as Cage describes them.8 Chance, according to Cage, involves various randomizing techniques applied to preselected materials; indeterminacy comprises vague notation, event-scores and other frameworks within which the unforeseeable choices of performers or sounds of the environment are welcomed. In both, a deliberate arrangement is followed by an unpredictable process of elaboration. This two-part procedure effectively splits the intentional creative act from the unexpected material form (understood as the perceptible aspect of the created work, whether this is variable with any number of different valid instantiations, or relatively stable), and in fact, appears deliberately designed to do so. Cage sets up aleatory procedures and invites real world contingencies seemingly in order to try to create a firewall between the will and the work. He wants to remove all traces of his own deliberate action from the work’s form. “What better technique than to leave no traces?” (S, 159).

Cage’s desire to evacuate the perceptibility of intentionality is all the more fascinating since it can’t be done. What could it mean for an artist to leave no traces? The existence of the work itself is a trace of the artist’s action. This is true whatever the form, and whether or not the human, intentional gestures and procedures that went into its production are readily identifiable or are hidden behind a randomizing filter. However, in works that were made using randomizing or indeterminate procedures, the perceptible traces of the artist’s intentional action are reduced to a minimum, just as they are minimal in Duchamp’s Fountain and Warhol’s Brillo Boxes.9 In these cases, intentionality is present in the work’s existence but not apparent in its detailed, particular form. Cage’s methods seem designed to cover his tracks, to prevent his intentionality from becoming sensuous, beyond the mere existence of the work. By attempting to split the will and the work, the deliberate action and the material form, and to leave no trace or perceptible relation between the two, Cage ends up adopting a fundamental dualism, one that maps easily onto the old dualism of mind and matter. In one of postmodernism’s constitutive moves, Cage tries to attain non-dualism by simply evicting mind and promoting the self-action of matter; but in so doing, he posits an unbridgable rift between the two.10 Mind can no more be abolished than chance. Cage regularly argues against dualism and causality, considering his philosophy one of “non-dualism”; however, the attempt to banish intention only severs it from the material form and enforces the duality. He writes: “If, at this point, one says, ‘Yes! I do not discriminate between intention and non-intention,’ the splits, subject-object, art-life, etc., disappear” (S, 14). Not discriminating between intention and non-intention means trying to relinquish intentionality, which ends up as an attempt to repress the fact of mind. In the continuation of one of the passages cited earlier, Cage states significantly: “Therefore error is fiction, has no reality in fact. Errorless music is written by not giving a thought to cause and effect. Any other kind of music always has mistakes in it. In other words there is no split between spirit and matter” (S, 168). Cage explicitly views intentionality (the possibility for error) as equivalent to both causality and dualism. In this view, aesthetic intention is akin to causation and the action of spirit upon matter; hence, if there is no intentionality, the material acts “on its own” without being caused or determined by an artist’s action. This is a version of the “bad picture” of intentionality criticized by Stanley Cavell, in which intention is considered an “internal, prior mental event causally connected with outward effects,” discussed recently by Walter Benn Michaels and Todd Cronan.11 It’s also a good expression of the dualistic anti-intentionalism that Cronan has appropriately called inverted cartesianism.12 Cage defines intention in this dualistic way, and thus rejects both intention and dualism; but the very fact of accepting the causal interpretation of intention instates the dualism he tries to avoid. Although the aleatory procedures are intended by Cage to break the causality of mind acting upon matter, the overall two-part set-up of the aesthetic action is radically causal because the first part of the act (setting up procedures) is separate from and determines the second (obtaining a material outcome), even if not in its particular details. It doesn’t matter if the results are uncontrolled or unpredictable, they are still direct consequences of the initial set-up. (If I don’t plan or control the ingredients in my chemistry experiment, my action is still the cause of the explosion.) It is significant that the term “result” is most appropriate for the outcome of Cage’s procedures (as opposed to a term like “form,” which implies that it has been consciously worked with and formed), as it accurately describes their nature as consequences of his prior action of coin-tossing. In using randomizing methods to try to avoid what he thinks is the “cause and effect” quality of intentionality, Cage splits the deliberate and the material aspects of the act and ironically ends up with a causal dualism.

Indeed, one might argue that the way to avoid the mind/matter dualism in art is to allow them to perceptibly intertwine through creative actions that are simultaneously intentional and open to the particularities and contingencies of the material. But Cage desires to make the rupture with intention perceptible, that is, to destroy any perceptible link between the act and the form. He wants his works to appear unmeant. Attempting to give the impression of natural unintentionality has a long history, from Diderot’s aesthetics of absorption (in Michael Fried’s terms) to Bed Head styling gel. Walter Benn Michaels correctly analyses Cage’s refusal of intentionality as the “radicalization of absorption” until it dialectically becomes its opposite, theatricality.13 He writes: “The goal for Cage was an art that, rivaling nature in its refusal of intentionality, would therefore exist as an art only insofar as it existed for the viewer.”14 Cage’s repression of intentionality becomes theatrical because his non-acting is necessarily done in the framework of performances in front of an audience, in the form of “occasions for experience” (S, 31), since if it were not then no one would know or care that he is not acting. In this sense, the ironic gap between the intention of unintentionality and the reality of intentionality could seem rather comic (“The rain, the city and silence itself have spoken! Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.” Or rather: “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Not me.” And again, in his next piece, “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Not me.” “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Not me.” “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Just the sound of the knock”). But unlike the Wizard of Oz, Cage is not a humbug, and his effort to do something unintentional seems entirely sincere and not meant to deceive. He seems unaware of the irony. He’s not deceptively trying to hide his authorship or intentionality, but sincerely trying not to be the author, attempting not to intend. There is nothing fraudulent about Cage’s work; the ingenuity with which he pursues his commitment to produce the unintended is apparent, and the inevitable failure of this effort should in no way diminish our admiration for it.

A few examples will help understand the inevitability of this failure. In order for the artist to “leave no traces,” to make the break with intention perceptible, the audience has to know that the material form of the work was not the immediate result of intentional design. However, the use of randomizing procedures in artworks cannot be perceived as such. If the composer does not explicitly state that the sounds were the result of aleatory operations, we assume that they were intentionally composed. Again ironically, in Cage’s aleatory works (the indeterminate ones are another case, which I’ll address below), the audience members can only know that these unintentional elements were unintentional if the composer tells them so – which calls attention to and reinforces the artist’s original, purposeful action. Cage has to say in a preface, program notes or other extramusical statement that he had used certain aleatory procedures to create the work: no one can tell upon listening to a musical composition that a certain sound was generated by chance or by will. But by stating this, the artist foregrounds the deliberate action which created the work, undermining the anti-intentionalism. For example, Cage’s Music of Changes (1951), one of his first experiments with aleatory methods, is a piano work composed using a method of tossing coins derived from the I Ching to determine the particular sounds, durations, dynamics, tempi and number of superposed sounds. Upon hearing it, avant-garde audiences thought it sounded much like Boulez’s or Webern’s serialism. According to Jean-Jacques Nattiez, “Music of Changes sounds like an atonal work inspired by Webern, and sounds even more Webernian than Boulez’s works, insofar as the silences play a leading role.”15 Nothing in the phenomenological experience of the work leads the audience to know that it was created with aleatory procedures and not by methods similar to those of Boulez or Webern. The piece premiered in 1952, and alongside his descriptions of the methods in letters and probably conversations among avant-garde circles, that year Cage also published an article, “To Describe the Process of Composition Used in Music of Changes and Imaginary Landscapes No. 4,” in which he detailed his processes (S, 57-59).16 If Cage hasn’t revealed his aleatory methods the audience assumes intentionality, and if he has, he advertises the deliberate procedures employed to remove it. This forces the artist to reconnect the two steps of the process, annulling the attempt to disown authorship.

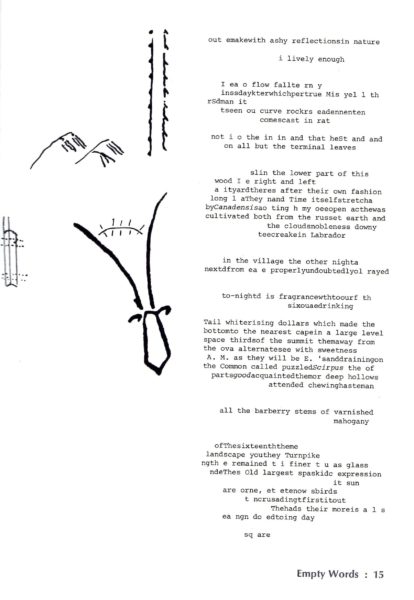

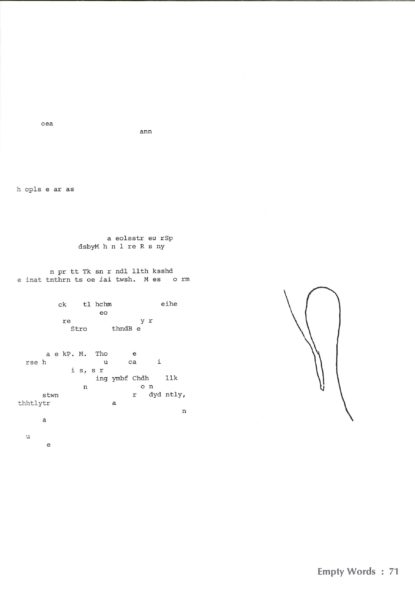

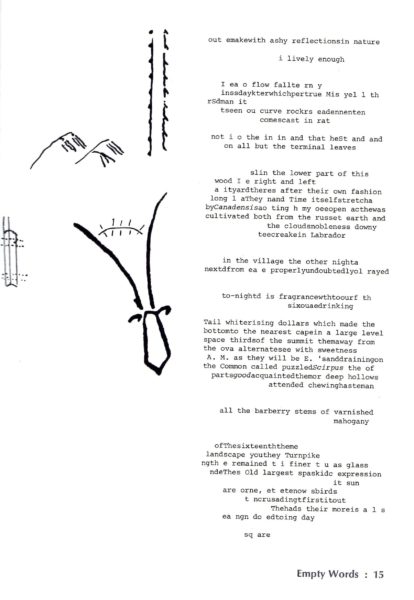

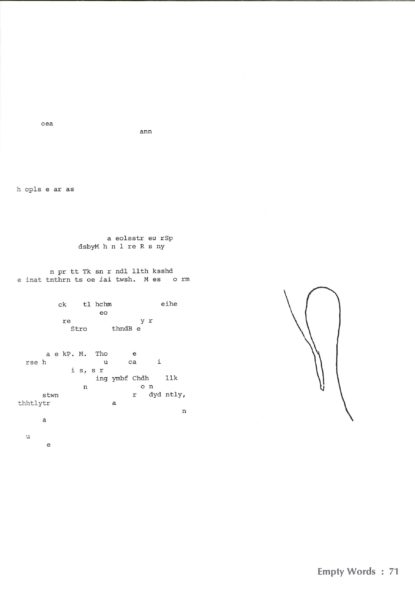

Similarly, Empty Words (1974) is a text intended for performance, divided into four parts, all of which are scattered with reproductions of drawings from Thoreau’s journal, and the last of which was accompanied by a film during the performances given by Cage. The text is made up of randomly selected very short citations from Thoreau’s writings. The first part is composed of phrases, words, syllables and letters, the second of words, syllables and letters, the third of syllables and letters, and the fourth of single letters. (Fig. 3) This work is part of Cage’s explicit attempt to overcome intentionality and meaning by destroying syntax and language’s semantic value. Shortly before his linguistic experimentations, first in Mureau (1970) and then Empty Words, he stated, “I have not yet carried language to the point to which I have taken musical sounds. I have not made noise with it. I hope to make something other than language from it. … I hope to let words exist, as I have tried to let sounds exist” (FTB, 113, 151). In the short prefaces to each part, Cage helpfully recounts his intentions and procedures: “Syntax: arrangement of the army (Norman Brown). Language free from syntax: demilitarization of language. … Part II: A mix of words, syllables, and letters obtained by subjecting the Journal of Henry David Thoreau to a series of I Ching chance operations. … Making language saying nothing at all. … Nothing has been worked on: a journal of circa two million words has been used to answer questions.”17 (Fig. 4) What makes the letter “o” found in the upper left part of this excerpt (in image 4) an extremely short citation of Thoreau’s journal, and not simply an “o” written in the old-fashioned intentional way? What makes that letter “h” below it on the left not just an “h” but part of Thoreau’s reflection about a hawk he saw on July 8, 1854? For us to know that what we see on the page are hacked-up bits of Thoreau’s journal and not just a series of composed letters, the author has to recount his action. Notwithstanding Cage’s insistence on non-intentionality, the interpretation and even “experience” of his work are very much dependent on the audience’s awareness of these intentional acts of the artist. The fact that there was an external source material is an essential factor in the interpretation of the text. Otherwise no syntax has been destroyed. In order to have the “experience” of the destruction of syntax, we must know that there had originally been a sentence with syntax from which that “o” had been taken. The importance of an audience’s awareness of the origin of the materials used in a work (whether subjected to aleatory procedures or not) is a large strain in postmodern art, and Cage’s insistence on his sources participates in this. When looking at Simon Starling’s Shedboatshed: Mobile Architecture No. 2, an installation that won the Turner prize in 2005, you see a shed; to begin to understand the work, you must know that it had once been a shed in Switzerland, it was dismantled and the boards were used to make a boat which was floated down the Rhine, and then it was dismantled again and made back into a shed in the museum. (Fig. 5) The artist intended that this invisible history should constitute an essential part of the work, and it must be thus be divulged somehow, in this case in a museum label. To the degree to which these works rely on such extra-artistic, extratextual or extramusical supports, they shine a spotlight on the author’s intentionality. The reference to sources highlights the process of transformation that those sources have undergone, which is a clear signpost pointing to the agent of transformation and the artist’s purposeful action.

Fig. 5 Simon Starling, Shedboatshed: Mobile Architecture, No. 2 (2005)

Cage believes that his use of aleatory techniques and indeterminacy annuls his aesthetic intentionality, but as we’ve seen, in the case of his randomizing procedures he has to actively call attention to his intentional action in order for them to be perceived. His highly indeterminate works that integrate real world contingencies may have been devised partly in order to make unintentionality and non-authorship unmistakably perceptible, since no one could possibly stage all the city sounds or rain or sneezing that may contribute to a performance of 4’33”. But in the case of such indeterminate works, in order for the sounds to be perceived as unintentional, the audience needs to be told that they are part of a work at all. Otherwise they’re just traffic or weather or sneezing with no possibility of being either intentional or unintentional. To make them perceptibly unintentional, the artist has to state somehow that “this is an artwork” (and that these occurrences are designated as unintentional elements of it), and the act of stating this, through giving the work a title and the other trappings of a performance, establishes the artist’s intentionality and authorship.

After hearing Cage perform Empty Words, Marjorie Perloff wrote: “It is poised between compositional game and reference, for all the time that we perceive only sounds, denuded of meaning, we are reminded in odd ways that this is after all a composition derived from Thoreau and that both words and images are on the verge of representing something.”18 What does it mean to say that these sounds have been denuded of meaning? And, simultaneously, are on the verge of representing something? The letters and syllables may have been isolated from a context in which they had had a particular meaning (the one intended by Thoreau), but they are not denuded of meaning altogether. They gain new meaning by becoming part of Empty Words. The fact of being elements in an artwork gives these sounds meaning, which may be interpreted in various ways. For an anti-intentionalist, Cage is quite generous in telling us his intentions (to free language from syntax, to turn language into “noise,” etc.) and this knowledge aids us in interpreting the meaning. Can one intend to destroy meaning… and succeed? No matter how much one chops up sentences into syllables and letters, one is still using material, wherever it came from, to make an artwork, which itself carries meaning. The intention to destroy meaning (here understood as Thoreau’s meaning) becomes a new form of meaning (Cage’s various meanings, however they may be interpreted). One may destroy syntax, but not meaning. Meaning is inherently part of the human creative act and cannot be abolished from the work as it is constitutive of the work. Cage thus fails to destroy meaning, just as he fails in his intention to act unintentionally. But since he unintentionally fails to act unintentionally, he succeeds after all in realizing his intention to act unintentionally, even if it is through unintentional intentionality. And since he succeeds in realizing this intention and thus acts intentionally despite everything, he fails because his intention was to act unintentionally. And so on. Cage’s aesthetics becomes an antinomy, where he both intentionally acts unintentionally and unintentionally acts intentionally, a situation that would have either amused or annoyed him, or both.

III.

All artists (and all humans) act both intentionally and unintentionally, and all art is made up of both intentional and unintentional elements, blended inextricably and often unidentifiably. What makes Cage’s case particular is that he desires to remove or minimize the intentional elements and tends to deny that he is the author of the unintentional elements. Within the context of an intentional action such as making an artwork, all sorts of unintentional things happen, ranging from serendipity to failure, passing through experiences we call experimentation, luck, accident, infelicity, error, and so on, depending on the artist’s skill in working with the contingencies of the material, whether or not the artist likes the effect and whether they want to use contingency as a tool, as Cage does. Artists may define a certain accident as an error, and another as a stroke of luck; or, like Cage, they may define all possible results to be simply valid, so that error and serendipity are impossible. But when Cage says not only that there is no error but that there is no intention, he makes a mistake; one can’t renounce design so easily. These definitions are intentional and reflect the artist’s taste. The fact that the physical form of the work includes elements involving differing degrees of control does not upset the fundamentally intentional nature of the overall act.19 This underlying intentionality is present also in what Cage calls indeterminacy, or the invitation of real world contingency into the work; indeterminacy simply involves a particularly high proportion of unintentional elements. Incorporating unexpected birdsong or car horns into a composition does not mean letting the sounds “act on their own,” as though they weren’t transformed when made part of a work; it is composing, using relatively uncontrollable and unpredictable tools and materials.

I am thus arguing here for an expanded view of aesthetic intentionality that comprises both the intentional and the immediately unintentional aspects of a work, since all of these aspects participate in the fundamentally intentional act of making an artwork. And the unintentional aspects include both the intentionally unintentional ones such as Cage’s aleatory results and real world contingencies, and the unintentionally unintentional ones such as my accidentally getting red paint on the brush when I’d meant blue (and my keeping the red blotch anyway in the final painting). Whether the materials are controlled or not, the overall action is intentional, and this is true no matter how aleatory or indeterminate its elements. An aesthetic action has two inalienably intentional moments, the beginning and the end: the decision to begin it and the decision to accept everything in it (no matter how unexpected) by signing, publishing, performing or showing it.20 What happens in the middle may have widely differing degrees of immediate intentionality and unintentionality, and even an indistinguishable blend of the two (for not only is it difficult for an audience to identify what exact elements are intentional and what are not, but sometimes this is true for the artist as well). But it is all inherently intentional on a larger level, because it is part of the process of creation and falls between those two moments. This overarching intentionality includes all unintentional elements or events that may intervene during the act of its creation (if my cat walks across my wet painting on the table and I leave its traces in the final form, this is ultimately intentional on my part), but not those unintentional occurrences that may happen to it after the creative act is finished and signed, such as craquelure over time or a light bulb in a Dan Flavin going out.21 And if the work is intended to evolve or weather over time, such as land art, then that intentionality is extended through the period of the physical life of the work, as the artist deliberately invites the dynamic contingencies of the materials to continue participating in the work indefinitely. Just as an accident or an error does not disturb the intentionality of the act—and indeed, their possibility is constitutive of an intentional act—the presence of unintentional and uncontrolled elements in an artwork in no way disturbs the overall intentionality of the work. Indeed, there would be no creativity without exploration of the unknown. This enlarged or overall aesthetic intentionality functionally overlaps with aesthetic agency or authorship, and when Cage denies one he tends to deny the other. In this context the term intentionality seems more precise than that of agency as it emphasizes the fundamentally deliberate nature of all creative actions. The concepts are not the same (generally, there is no intention without agency, but there can be agency without intention), but if we accept that artworks are fundamentally intentional even including their unintentional aspects, then aesthetic agency and intentionality become operatively synonymous. If there’s an author, there’s intention, and vice versa.

For over 150 years, the arts have been integrating more and more contingency into their fabric. Baudelaire wrote in The Painter of Modern Life in 1863, “Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent.”22 Contingency describes that which is possible but not necessary, and generally that which we feel could happen otherwise or not at all, could just as well happen or not happen. Contingency is not chance or the absence of cause: contingencies are particularities and events that have causes and participate in the deterministic and dynamic complexity of the world, but are experienced as unexpected, unpredictable and uncontrollable. Though artists have obviously always dealt with the contingencies or unpredictable aspects of their materials, in the modern era these have vastly expanded in diversity, and some artists, especially in the postmodern age, have moved from simply working with the unavoidable contingencies of the material to actively inviting and foregrounding real world contingency and unpredictability. In the context of aesthetics, Cage calls this real world contingency indeterminacy, Roger Caillois calls it accident, Dominic McIver Lopes calls it happenstance.23 Some media are particularly open to contingency: the ephemeral temporality and situatedness of happenings, interactive performances and photography make them especially propitious to the inclusion of contingency. But even highly skilled artists working with the most traditional materials and methods are also constantly playing with the unexpected, often in more subtle ways. No matter how much contingency, accident, or unintentionality is present, no matter whether the contingencies worked and played with are those of a more traditional material like paint or those of the real world, there is always a dynamic balance of contingency and agency, unintentionality and intentionality, and the fundamental intentional structure of the artwork remains, even if only in the basic act of stating that such and such a found object is a work.

The question is how to make the balance of contingency and intention perceptible—a question too large for this essay. When Cage attempts to make his intentionality invisible, he tends to obstruct the perceptible interrelation of contingency and agency that exists in very diverse ways throughout creative work.24 Cage writes: “The idea of relation (the idea: 2) being absent, anything (the idea: 1) may happen” (S, 59). Through his aleatory and indeterminate methods, he eliminates not only the idea but the sensuous reality of specific relation (although he advocates a metaphysical sort of all-relatedness or “interpenetration” which remains abstract). Comparing Joyce’s Finnegans Wake with Cage’s Empty Words, it’s clear that the extraordinarily rich polysemantic layering in Joyce’s clusters of linguistic fragments and inventions could not have been generated randomly, but rather the deliberate configuration of the material allows its unexpected contingencies and particularities to resonate together, highlighting their interplay. Whereas in Empty Words, the semantic richness has been drained from the material at the same rate as intentional design, which, far from overcoming the duality, makes it starker. By attempting to leave no traces, Cage forgoes the possibility of intimate perceptible relations between contingency and agency. Forming rich and non-arbitrary relations between the unintentional and the intentional elements of art—between that which could just as well have happened otherwise, and that which could not have been done by chance—may lead toward overcoming these dualisms.25 This is a much more promising path than through attempting to evacuate mind.

Notes

I.

In 1954, John Cage gave a talk entitled “45’ for a Speaker.”1 According to its preface, the text was composed using bits taken from previously written lectures, new material, and scripted noises and gestures such as snoring and blowing his nose, the timing of which was determined by aleatory operations. For the new material, Cage made a list of 32 subjects, and when the coin-toss dictated, he wrote a passage on that topic. Among subjects such as structure, time, sound, silence, chance, theater, non-dualism, listening as ignorance, and asymmetry of probability, one finds the rubric “error.” And so, within this wide-ranging statement of his aesthetics are to be found scattered reflections on error. For example: “The thing to do is to keep the head alert but empty. Things come to pass, arising and disappearing. There can then be no consideration of error. Things are always going wrong” (S, 187). The category of error belongs to an aesthetic approach that Cage refuses; for him, all sounds are welcome in the composition. These ideas should be understood in the context of his use of aleatory (randomizing) techniques in the compositional process—such as tossing coins, crumpling paper and placing notes in the intersections of the folds, and using paper imperfections and star charts to determine the score—as well as his practices of allowing the performers a large freedom of interpretation and inviting the contingencies of the environment to contribute to the work. Perhaps his most open work is the 1962 event-score 0’00” (4’33” No. 2), whose full score consists in the sentence: “In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action.” (Fig. 1) In adopting aleatory methods and incorporating environmental contingency, he rejects the compositional paradigm according to which there can be errors. An error, in the context of creative work, may be defined as an action that is done contrary to the actor’s intention. The idea of error only makes sense when there is an intention, when a creator’s head is not “empty”: the empty head in the above quote is not only that of the audience but that of the composer, who shouldn’t make decisions but simply allow things to come to pass, arise and disappear. Because the composer doesn’t control the events, “things are always going wrong.” This is one of Cage’s paradoxical punchlines, as he has switched points of view; from the point of view of the intentionalist, such uncontrolled events are considered as “always going wrong.” For Cage, there can be no errors or failures in his musical composition and production since all possible outcomes of the process are equally valid. As he refuses the category of the “rightness” of any element of aesthetic production, whether that “rightness” is understood as subjective or as participating in a formal compositional system, it is logical to refuse that of “error” as well. “No error. And no wondering about what’s next” (S, 192).

Cage’s refusal of the possibility of error should be taken in the context of those musical practices he was actively rejecting at the time: European traditional and avant-garde composition, based in either traditional harmony or atonal counterpoint, in both of which the idea of error was a reality, though not necessarily a hard and fast one. In traditional tonal harmony, every dissonance must be justified by a subsequent resolution, and if it isn’t, this is considered a wrong note or an error. And in the 1950s atonal music was no longer in the early liberational phase of Schoenberg’s “emancipation of the dissonance” from the requirement of tonal resolution, but in the codification phase of Boulez’ generalized serialism, wherein if you compose a D where the row demands an E, you’ve made an “error.” In a way, Cage wanted to extend Schoenberg’s emancipation of the dissonance beyond that of half-tones and into the real-world dissonance of noise and environmental sounds. But Cage’s repudiation of the concept of error goes beyond his critique of traditional and avant-garde composition and takes aim at all aesthetics involving intentional control, whether that control is exercised within or outside of a compositional system. “A technique to be useful (skillful, that is) must be such that it fails to control the elements subjected to it” (S, 154), he says, with characteristic paradox. Cage’s desire to efface intentionality from the compositional process is partially due to the influence of Zen Buddhism, but also to the anti-expressivity bent among the mid-century avant-garde. The other composers associated with Darmstadt in the 1950s were seeking to eliminate personality and expressivity through the quasi-mechanistic determinism of generalized serialism; Cage and others in the New York School through aleatory and indeterminate methods. Cage took this anti-expressivity to an extreme by attempting to efface the intentionality and even the agency of the composer entirely, and in so doing became perhaps the clearest theorist of aesthetic anti-intentionalism.

Elsewhere in the same lecture, he writes: “Error is drawing a straight line between anticipation of what should happen and what actually happens. What actually happens is however in a total not linear situation and is responsible generally. Therefore error is fiction, has no reality in fact. Errorless music is written by not giving a thought to cause and effect. Any other kind of music always has mistakes in it” (S, 167-68). Cage turns on its head the intuitive description of aesthetic error as an action that is done contrary to the actor’s intention, and here gives two descriptions in its place. We have already seen one of them in the earlier quote, that for him error is fiction and doesn’t actually exist. The other one equates error with intentionality and control, basically saying that any intentional attempt to control an outcome is erroneous: error is the attempt to create a direct relation between “anticipation of what should happen and what actually happens.” What happens should be unobstructed by the composer’s anticipation, decision-making, planning or intention. Indeed, the party “responsible” for the event is “what actually happens,” not the composer. Similarly, Cage states in another passage, “I will not disturb by my concern the structure of anything that is going to be acting; to act is miracle and needs everything and every me out of the way. An error is simply a failure to adjust immediately from a preconception to an actuality” (S, 170-71). Here the actor is not the composer, but “anything that is going to be acting,” with a metaphysical resonance. The phrase “to act is miracle” is telling: while the verb normally implies a subject, the infinitive form removes the verb from any particular instantiation and the human agent is effaced by the arrival of an uncontrolled and anonymous “miracle.” Cage considers an act to be an event, or perhaps, he thinks that an act should be an event. The “failure to adjust immediately from a preconception to an actuality” means the attempt to control the process, to refuse the validity of any unexpected actuality. “A ‘mistake’ is beside the point, for once anything happens it authentically is” (S, 59). In Cage’s aesthetics, the only error is intentionality itself. No intentionality, no error.

Quite logically, Cage relates the impossibility of error on the part of the composer to the impossibility of error or “misunderstanding” on the part of the audience. He states: “I am interested in the fact that [sounds] are there, and not in the will of the composer. A ‘correct’ understanding doesn’t interest me. With a music process, there is no ‘correct understanding’ anywhere. And consequently, no all-pervasive ‘misunderstanding’ either.”2 Although it is indeed difficult to define exactly what a correct understanding of a musical piece might consist in, the question is ultimately no more delicate than the same question regarding painting or literature. Just as the ideas of “rightness” and error participate in an aesthetic approach Cage refuses, so do those of understanding and misunderstanding. Rather than understanding, for him there is only “experience”: “I think the most pointed way to put this distinction is by using the word ‘understanding’ as opposed to ‘experience.’ Many people think that if they are able to understand something they will be able to experience it, but I don’t think that’s true. … I think that we must be prepared for experience not by understanding anything, but rather by becoming open-minded.”3 “[My works are] not objects, and to approach them as objects is to utterly miss the point. They are occasions for experience” (S, 31). It follows that aesthetic experience is particular to the person experiencing, and Cage is quite clear that everyone’s experience of his work is different. “I think each person should listen in his own way, and if there are too many things for him to listen to, and in that complex he then listens to whatever, he will have his own experience, and there will be a strength and validity in that” (CC, 236). In his interviews with Cage, Daniel Charles puts this succinctly: “So it’s also an invitation to plurality or multiplicity. Your experience is one thing, mine is different. The works signed ‘John Cage’ don’t belong to their author. They are just as much what you make of them as what I make of them, because you are there and I am here,” to which Cage responds, “I agree completely” (FTB, 234-35). We would expect, then, that in an aesthetic philosophy based upon experience and the impossibility of error or misunderstanding, the concepts of meaning and truth would be rejected as irrelevant as well. Cage does not use these terms often, but they appear occasionally, precisely in the context of aesthetic “experience.” When in their interviews Daniel Charles remarked that Cage “felt at home” in the philosophy of Wittgenstein, Cage answered: “That’s right. But I didn’t understand everything. I retained this sentence: ‘Something’s meaning is how you use it.’ … Everything we use is legitimate, since we use it. That is a situation of fact. There is no ‘meaning’ beyond this situation of fact. Everything is possible. … Use rather refers to experience.”4 Beyond Cage’s “use” of Wittgenstein, what counts here is his explicit equating of meaning, use and experience. Instead of saying that his works have no meaning, he embraces the definition of a work’s meaning as the audience’s particular experience. Interestingly, when he takes a similar stance on the notion of truth, he associates it with “form”: “Form … is wherever you are and there is no place where it isn’t. Highest truth, that is” (S, 186). The “form” of a work is equivalent to “your” experience, and to truth: meaning = use = experience = form = truth. Cage is consistent in his aesthetic relativism.

Cage is right when he asserts that the idea of error only makes sense within an intentionalist perspective. Playing the note D can only be considered an error if I had intended to play F or some other note instead. Using red paint is a mistake only in the context of having meant to use blue (or any other color but red); otherwise, it’s just the act of using red paint. Likewise, the potential for error or failure is constitutive of intentionality. Walter Benn Michaels, working with Elizabeth Anscombe’s theory of intention, writes: “[Anscombe’s] point is that the intentional structure of the failed act is the same as the intentional structure of the successful one.”5 The question is what it means to say that intentionality itself is an error, and whether it’s possible to get “every me out of the way” and thus renounce aesthetic intentionality. Since error doesn’t exist outside of an intentionalist paradigm, the statement that intentionality is an error is self-contradictory. Intentionality (like red paint) can only be considered an error if I had intended something else; for there to be an error, there must be some intention against which the act is defined as an error. What Cage intends is unintentionality—he intends not to intend—but this constitutive paradox of Cage’s aesthetics is not only a logical contradiction but is impossible to fully put into practice. In what follows I’ll focus on Cage’s effort to abdicate intentionality and argue that he intends not to intend, but fails.

II.

How can we interpret Cage’s refusal of aesthetic intentionality? First of all, despite many statements which state or imply that the artist should somehow keep out of the process, Cage occasionally says explicitly that some intentional action takes place, basically by creating the conditions of possibility for unpredictable results. He desires this action to be minimal, and often conceives of it in terms of “asking questions” to be answered by the aleatory operations. He asks, “Why do they call me a composer, then, if all I do is ask questions?” (S, 48). Asking a question involves as much intention as making a statement, as does the incorporation of the answer into an artwork. “Not abandoning [the artist’s role as a creator], simply changing it from the responsibility of making choices to the responsibility of asking questions.”6 Although he occasionally makes such admissions, in his aesthetic writings and interviews he most often says or implies that he wants to avoid artistic intentionality and agency. The method of asking questions of the random oracle is an attempt to find an answer to his central question, that of how to remove himself as much as possible from the process and “let” the material act on its own, “once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of [life’s] way and lets it act of its own accord” (S, 12; 95). “What if a B flat, as they say, just comes to me? How can I get it to come to me of itself, not just pop up out of my memory, taste, and psychology?” (S, 48). Cage desires to transfer agency to the material, and let the B flat act on its own. “It is clear that ways must be discovered that allow noises and tones to be just noises and tones, not exponents subservient to [a composer’s] imagination” (S, 69). But despite these statements and the aleatory methods used, intentionality has obviously not been eliminated. First and foremost, even before intending to let the B flat act of its own accord, Cage intends to create a work. His techniques allow a greater than average inclusion of uncontrolled elements, but the fundamental creative intention remains the same. Without it, and if he truly did nothing, there would be no work. Cage may not like the term “work” (“All I am doing is directing attention to the sounds of the environment” [FTB, 98]), and we may prefer to replace it with “production,” “performance,” etc., but his productions fulfill the minimal condition of creative works: they would not exist without the artist’s intentional creative action. The sounds of the environment would still exist, but not the elaborate direction of attention to them, in the particular ways that Cage signs.

Rather than acting intentionally in a straightforward way, then, Cage intends to act unintentionally, or that is, he intentionally creates the conditions for a partially unintentional or uncontrolled event.7 He selects the elements that will then be arranged by coin-tossings; he creates the deck and then shuffles it before dealing; he sets up a framework involving time, place, title and audience, and then invites environmental contingencies to become part of the work. Intentionality remains intact, especially at the early stage of the process, even if in the second stage, the creation of an unpredictable result, it is perturbed. This intentionality is located in a moment prior to the traditional one of direct compositional choice: rather than creating a work directly, Cage first intentionally devises a procedure (the application of aleatory or indeterminate methods to x or y material), and then lets that procedure operate without his intervention. The locus of intentionality in his work lies in the invention of the procedure and not in the direct creation of the perceptible form. The creative process thus has two distinct phases for Cage: first the intentional determination of materials, conditions, parameters, frameworks and procedures, and secondly the resulting unpredictable production of a work or event. This two-step process is to be found in both “chance” and “indeterminacy,” as Cage describes them.8 Chance, according to Cage, involves various randomizing techniques applied to preselected materials; indeterminacy comprises vague notation, event-scores and other frameworks within which the unforeseeable choices of performers or sounds of the environment are welcomed. In both, a deliberate arrangement is followed by an unpredictable process of elaboration. This two-part procedure effectively splits the intentional creative act from the unexpected material form (understood as the perceptible aspect of the created work, whether this is variable with any number of different valid instantiations, or relatively stable), and in fact, appears deliberately designed to do so. Cage sets up aleatory procedures and invites real world contingencies seemingly in order to try to create a firewall between the will and the work. He wants to remove all traces of his own deliberate action from the work’s form. “What better technique than to leave no traces?” (S, 159).

Cage’s desire to evacuate the perceptibility of intentionality is all the more fascinating since it can’t be done. What could it mean for an artist to leave no traces? The existence of the work itself is a trace of the artist’s action. This is true whatever the form, and whether or not the human, intentional gestures and procedures that went into its production are readily identifiable or are hidden behind a randomizing filter. However, in works that were made using randomizing or indeterminate procedures, the perceptible traces of the artist’s intentional action are reduced to a minimum, just as they are minimal in Duchamp’s Fountain and Warhol’s Brillo Boxes.9 In these cases, intentionality is present in the work’s existence but not apparent in its detailed, particular form. Cage’s methods seem designed to cover his tracks, to prevent his intentionality from becoming sensuous, beyond the mere existence of the work. By attempting to split the will and the work, the deliberate action and the material form, and to leave no trace or perceptible relation between the two, Cage ends up adopting a fundamental dualism, one that maps easily onto the old dualism of mind and matter. In one of postmodernism’s constitutive moves, Cage tries to attain non-dualism by simply evicting mind and promoting the self-action of matter; but in so doing, he posits an unbridgable rift between the two.10 Mind can no more be abolished than chance. Cage regularly argues against dualism and causality, considering his philosophy one of “non-dualism”; however, the attempt to banish intention only severs it from the material form and enforces the duality. He writes: “If, at this point, one says, ‘Yes! I do not discriminate between intention and non-intention,’ the splits, subject-object, art-life, etc., disappear” (S, 14). Not discriminating between intention and non-intention means trying to relinquish intentionality, which ends up as an attempt to repress the fact of mind. In the continuation of one of the passages cited earlier, Cage states significantly: “Therefore error is fiction, has no reality in fact. Errorless music is written by not giving a thought to cause and effect. Any other kind of music always has mistakes in it. In other words there is no split between spirit and matter” (S, 168). Cage explicitly views intentionality (the possibility for error) as equivalent to both causality and dualism. In this view, aesthetic intention is akin to causation and the action of spirit upon matter; hence, if there is no intentionality, the material acts “on its own” without being caused or determined by an artist’s action. This is a version of the “bad picture” of intentionality criticized by Stanley Cavell, in which intention is considered an “internal, prior mental event causally connected with outward effects,” discussed recently by Walter Benn Michaels and Todd Cronan.11 It’s also a good expression of the dualistic anti-intentionalism that Cronan has appropriately called inverted cartesianism.12 Cage defines intention in this dualistic way, and thus rejects both intention and dualism; but the very fact of accepting the causal interpretation of intention instates the dualism he tries to avoid. Although the aleatory procedures are intended by Cage to break the causality of mind acting upon matter, the overall two-part set-up of the aesthetic action is radically causal because the first part of the act (setting up procedures) is separate from and determines the second (obtaining a material outcome), even if not in its particular details. It doesn’t matter if the results are uncontrolled or unpredictable, they are still direct consequences of the initial set-up. (If I don’t plan or control the ingredients in my chemistry experiment, my action is still the cause of the explosion.) It is significant that the term “result” is most appropriate for the outcome of Cage’s procedures (as opposed to a term like “form,” which implies that it has been consciously worked with and formed), as it accurately describes their nature as consequences of his prior action of coin-tossing. In using randomizing methods to try to avoid what he thinks is the “cause and effect” quality of intentionality, Cage splits the deliberate and the material aspects of the act and ironically ends up with a causal dualism.

Indeed, one might argue that the way to avoid the mind/matter dualism in art is to allow them to perceptibly intertwine through creative actions that are simultaneously intentional and open to the particularities and contingencies of the material. But Cage desires to make the rupture with intention perceptible, that is, to destroy any perceptible link between the act and the form. He wants his works to appear unmeant. Attempting to give the impression of natural unintentionality has a long history, from Diderot’s aesthetics of absorption (in Michael Fried’s terms) to Bed Head styling gel. Walter Benn Michaels correctly analyses Cage’s refusal of intentionality as the “radicalization of absorption” until it dialectically becomes its opposite, theatricality.13 He writes: “The goal for Cage was an art that, rivaling nature in its refusal of intentionality, would therefore exist as an art only insofar as it existed for the viewer.”14 Cage’s repression of intentionality becomes theatrical because his non-acting is necessarily done in the framework of performances in front of an audience, in the form of “occasions for experience” (S, 31), since if it were not then no one would know or care that he is not acting. In this sense, the ironic gap between the intention of unintentionality and the reality of intentionality could seem rather comic (“The rain, the city and silence itself have spoken! Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.” Or rather: “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Not me.” And again, in his next piece, “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Not me.” “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Not me.” “Knock knock.—Who’s there?—Just the sound of the knock”). But unlike the Wizard of Oz, Cage is not a humbug, and his effort to do something unintentional seems entirely sincere and not meant to deceive. He seems unaware of the irony. He’s not deceptively trying to hide his authorship or intentionality, but sincerely trying not to be the author, attempting not to intend. There is nothing fraudulent about Cage’s work; the ingenuity with which he pursues his commitment to produce the unintended is apparent, and the inevitable failure of this effort should in no way diminish our admiration for it.

A few examples will help understand the inevitability of this failure. In order for the artist to “leave no traces,” to make the break with intention perceptible, the audience has to know that the material form of the work was not the immediate result of intentional design. However, the use of randomizing procedures in artworks cannot be perceived as such. If the composer does not explicitly state that the sounds were the result of aleatory operations, we assume that they were intentionally composed. Again ironically, in Cage’s aleatory works (the indeterminate ones are another case, which I’ll address below), the audience members can only know that these unintentional elements were unintentional if the composer tells them so – which calls attention to and reinforces the artist’s original, purposeful action. Cage has to say in a preface, program notes or other extramusical statement that he had used certain aleatory procedures to create the work: no one can tell upon listening to a musical composition that a certain sound was generated by chance or by will. But by stating this, the artist foregrounds the deliberate action which created the work, undermining the anti-intentionalism. For example, Cage’s Music of Changes (1951), one of his first experiments with aleatory methods, is a piano work composed using a method of tossing coins derived from the I Ching to determine the particular sounds, durations, dynamics, tempi and number of superposed sounds. Upon hearing it, avant-garde audiences thought it sounded much like Boulez’s or Webern’s serialism. According to Jean-Jacques Nattiez, “Music of Changes sounds like an atonal work inspired by Webern, and sounds even more Webernian than Boulez’s works, insofar as the silences play a leading role.”15 Nothing in the phenomenological experience of the work leads the audience to know that it was created with aleatory procedures and not by methods similar to those of Boulez or Webern. The piece premiered in 1952, and alongside his descriptions of the methods in letters and probably conversations among avant-garde circles, that year Cage also published an article, “To Describe the Process of Composition Used in Music of Changes and Imaginary Landscapes No. 4,” in which he detailed his processes (S, 57-59).16 If Cage hasn’t revealed his aleatory methods the audience assumes intentionality, and if he has, he advertises the deliberate procedures employed to remove it. This forces the artist to reconnect the two steps of the process, annulling the attempt to disown authorship.

Similarly, Empty Words (1974) is a text intended for performance, divided into four parts, all of which are scattered with reproductions of drawings from Thoreau’s journal, and the last of which was accompanied by a film during the performances given by Cage. The text is made up of randomly selected very short citations from Thoreau’s writings. The first part is composed of phrases, words, syllables and letters, the second of words, syllables and letters, the third of syllables and letters, and the fourth of single letters. (Fig. 3) This work is part of Cage’s explicit attempt to overcome intentionality and meaning by destroying syntax and language’s semantic value. Shortly before his linguistic experimentations, first in Mureau (1970) and then Empty Words, he stated, “I have not yet carried language to the point to which I have taken musical sounds. I have not made noise with it. I hope to make something other than language from it. … I hope to let words exist, as I have tried to let sounds exist” (FTB, 113, 151). In the short prefaces to each part, Cage helpfully recounts his intentions and procedures: “Syntax: arrangement of the army (Norman Brown). Language free from syntax: demilitarization of language. … Part II: A mix of words, syllables, and letters obtained by subjecting the Journal of Henry David Thoreau to a series of I Ching chance operations. … Making language saying nothing at all. … Nothing has been worked on: a journal of circa two million words has been used to answer questions.”17 (Fig. 4) What makes the letter “o” found in the upper left part of this excerpt (in image 4) an extremely short citation of Thoreau’s journal, and not simply an “o” written in the old-fashioned intentional way? What makes that letter “h” below it on the left not just an “h” but part of Thoreau’s reflection about a hawk he saw on July 8, 1854? For us to know that what we see on the page are hacked-up bits of Thoreau’s journal and not just a series of composed letters, the author has to recount his action. Notwithstanding Cage’s insistence on non-intentionality, the interpretation and even “experience” of his work are very much dependent on the audience’s awareness of these intentional acts of the artist. The fact that there was an external source material is an essential factor in the interpretation of the text. Otherwise no syntax has been destroyed. In order to have the “experience” of the destruction of syntax, we must know that there had originally been a sentence with syntax from which that “o” had been taken. The importance of an audience’s awareness of the origin of the materials used in a work (whether subjected to aleatory procedures or not) is a large strain in postmodern art, and Cage’s insistence on his sources participates in this. When looking at Simon Starling’s Shedboatshed: Mobile Architecture No. 2, an installation that won the Turner prize in 2005, you see a shed; to begin to understand the work, you must know that it had once been a shed in Switzerland, it was dismantled and the boards were used to make a boat which was floated down the Rhine, and then it was dismantled again and made back into a shed in the museum. (Fig. 5) The artist intended that this invisible history should constitute an essential part of the work, and it must be thus be divulged somehow, in this case in a museum label. To the degree to which these works rely on such extra-artistic, extratextual or extramusical supports, they shine a spotlight on the author’s intentionality. The reference to sources highlights the process of transformation that those sources have undergone, which is a clear signpost pointing to the agent of transformation and the artist’s purposeful action.

Fig. 5 Simon Starling, Shedboatshed: Mobile Architecture, No. 2 (2005)

Cage believes that his use of aleatory techniques and indeterminacy annuls his aesthetic intentionality, but as we’ve seen, in the case of his randomizing procedures he has to actively call attention to his intentional action in order for them to be perceived. His highly indeterminate works that integrate real world contingencies may have been devised partly in order to make unintentionality and non-authorship unmistakably perceptible, since no one could possibly stage all the city sounds or rain or sneezing that may contribute to a performance of 4’33”. But in the case of such indeterminate works, in order for the sounds to be perceived as unintentional, the audience needs to be told that they are part of a work at all. Otherwise they’re just traffic or weather or sneezing with no possibility of being either intentional or unintentional. To make them perceptibly unintentional, the artist has to state somehow that “this is an artwork” (and that these occurrences are designated as unintentional elements of it), and the act of stating this, through giving the work a title and the other trappings of a performance, establishes the artist’s intentionality and authorship.

After hearing Cage perform Empty Words, Marjorie Perloff wrote: “It is poised between compositional game and reference, for all the time that we perceive only sounds, denuded of meaning, we are reminded in odd ways that this is after all a composition derived from Thoreau and that both words and images are on the verge of representing something.”18 What does it mean to say that these sounds have been denuded of meaning? And, simultaneously, are on the verge of representing something? The letters and syllables may have been isolated from a context in which they had had a particular meaning (the one intended by Thoreau), but they are not denuded of meaning altogether. They gain new meaning by becoming part of Empty Words. The fact of being elements in an artwork gives these sounds meaning, which may be interpreted in various ways. For an anti-intentionalist, Cage is quite generous in telling us his intentions (to free language from syntax, to turn language into “noise,” etc.) and this knowledge aids us in interpreting the meaning. Can one intend to destroy meaning… and succeed? No matter how much one chops up sentences into syllables and letters, one is still using material, wherever it came from, to make an artwork, which itself carries meaning. The intention to destroy meaning (here understood as Thoreau’s meaning) becomes a new form of meaning (Cage’s various meanings, however they may be interpreted). One may destroy syntax, but not meaning. Meaning is inherently part of the human creative act and cannot be abolished from the work as it is constitutive of the work. Cage thus fails to destroy meaning, just as he fails in his intention to act unintentionally. But since he unintentionally fails to act unintentionally, he succeeds after all in realizing his intention to act unintentionally, even if it is through unintentional intentionality. And since he succeeds in realizing this intention and thus acts intentionally despite everything, he fails because his intention was to act unintentionally. And so on. Cage’s aesthetics becomes an antinomy, where he both intentionally acts unintentionally and unintentionally acts intentionally, a situation that would have either amused or annoyed him, or both.

III.

All artists (and all humans) act both intentionally and unintentionally, and all art is made up of both intentional and unintentional elements, blended inextricably and often unidentifiably. What makes Cage’s case particular is that he desires to remove or minimize the intentional elements and tends to deny that he is the author of the unintentional elements. Within the context of an intentional action such as making an artwork, all sorts of unintentional things happen, ranging from serendipity to failure, passing through experiences we call experimentation, luck, accident, infelicity, error, and so on, depending on the artist’s skill in working with the contingencies of the material, whether or not the artist likes the effect and whether they want to use contingency as a tool, as Cage does. Artists may define a certain accident as an error, and another as a stroke of luck; or, like Cage, they may define all possible results to be simply valid, so that error and serendipity are impossible. But when Cage says not only that there is no error but that there is no intention, he makes a mistake; one can’t renounce design so easily. These definitions are intentional and reflect the artist’s taste. The fact that the physical form of the work includes elements involving differing degrees of control does not upset the fundamentally intentional nature of the overall act.19 This underlying intentionality is present also in what Cage calls indeterminacy, or the invitation of real world contingency into the work; indeterminacy simply involves a particularly high proportion of unintentional elements. Incorporating unexpected birdsong or car horns into a composition does not mean letting the sounds “act on their own,” as though they weren’t transformed when made part of a work; it is composing, using relatively uncontrollable and unpredictable tools and materials.