1. Retrospect

Most retrospectives on Hugh Kenner’s career at some point mention the devoted thoroughness with which Kenner obeyed Ezra Pound’s injunction: “You have an obligation to visit the great men of your own time.”1 Kenner’s life-long devotion to Modernism springs out of the 1948 visit with Pound at St. Elizabeths in which the injunction was uttered—as does, perhaps, his magnum opus, The Pound Era. Other books surely sprang from other visits—with Samuel Beckett and Wyndham Lewis, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, and T.S. Eliot.

Indeed, Kenner seems to have elevated the visit into something like a method. Not without cause, Kenner’s Modernism has been understood as a celebration of the great man theory of modernism, of an artistic era shaped by close-up encounters with powerful imaginations and their consequential doings.

And yet there is another abiding interest in Kenner’s work: in the shaping force of technology and its influence on human action, and over the workings of the imagination. Kenner’s other master, also present at that fateful asylum visit, was the young English professor Marshall McLuhan, whose techno-determinism left its own imprint on Kenner’s work.

And so while the acknowledgements of the Pound Era begin with “Ezra Pound, to start with,”2 the dedication of his Mechanic Muse is “In Memoriam Etaoin Shrdlu.”3 Etaoin Shrdlu, as Kenner explains in the bravura opening of that 1987 book, was a frequent protagonist in the newspaper in the days of linotype setting; a nonce name the machine operator would enter to cancel a line to type after a mistake was made. Etaoin Shrdlu entered the news because the machine made the pathway for them to appear: composed of the 12 most frequently used letters in English, arrayed down the leftmost column of the linotype machine so they had the shortest distance to travel.4

In The Mechanic Muse, Kenner describes Modernism as a particular mode of accelerating technological transformation in which “every thinkable human activity save perhaps the reproductive was being mapped onto machinery” (MM, 7). It is, on the one hand, an era of “transparent technology”—in which the forming and deforming links and gears are visible to the eye. (The contrast is with the “screen-and-keyboard terminal” of postmodern technology, about which “your eye will tell you nothing” [MM, 10].) And yet what your eye tells you about modern technology is the curious and sometimes damaging unfitness for the hand that it is meant to extend and supplement, and the way that this lack of fit exercises an agency of its own. Kenner articulates this lack of fit as technology’s own principle: “the way to imitate a human activity is never to replicate the human action” (MM, 7).

Thus, the way a linotype machine works to replicate the activity of the skilled human compositor (creating a page of newsprint) does not involve replicating his actions—“picking letters up one by one and setting them in place”—rather, “matrices would slide down from magazines onto a moving belt for delivery onto the line’s incrementing array” (MM, 8). This mechanism had great advantages when it came to publishing newspapers, but it had deleterious effects on linotype operators. Due to an uncomfortable mismatch between machinic efficiency and human dexterity, the linotype operator has to make 51% of his keystrokes with his “left little finger” (MM, 5).

Modernism conceived this way is, distinctively, “those years, when human behavior, e.g. movements of one’s left little finger, could be inflected by imperatives one needn’t know about” (MM, 9). And those unknown imperatives produced, first and foremost, new forms of life, many of them disorienting and uncomfortable: crowd life, Fordist life, life coerced into clock-bound synchrony; and new forms of art that matter insofar as they orient us to these uncomfortable coercions and synchronizations.

These two different accounts of Modernism, defined on the one hand by powerful people and effective imaginations, and on the other by powerful imperatives that “engulf[ed] people” in their effectiveness (MM, 9), produce not just two accounts of art, but two different ways of understanding the critical task. A dedication to “Ezra Pound, to start with” might set you out on long journeys: to Venice, to wait for the doors of Santa Maria dei Miracoli to be unlocked “at the behest of three words” of the Cantos (“mermaids, that carving”). One visits to confirm that they are there, to see that they are as they have been described, and to affirm that their description tells you what you need to know about “how our epoch was extricated from the fin de siècle” by the work of great men: “I cannot but endorse the accuracy of perception that set in array the words that drew me on.”5

Whereas to “memorialize” Etoain Shrdlu is to retroactively acknowledge one’s determination by the impersonal mechanic forces that set things in array. Why retroactively? If the first of Kenner’s principles of technology described the non-mimetic, inhuman efficiency of action, the second describes the explanatory opacity that follows when inhuman powers determine the shape of human actions. Modernist technology makes actions, and specifically authorial actions, the sort of thing that are explicable, indeed detectable, as actions only in retrospect. What are the crucial features of Modernist writing? What is it that the artist makes, and where is the work of invention realized? In the Modernist text, explanation or interpretation will appear always as a kind of retrospective surprise: “the resulting pressures on human behavior are apt to elude foresight utterly, and be occulted from most present sight, to leave hindsight flabbergasted” (MM, 8).

For Kenner, the opacity of the relation between the occulted present and interpretive hindsight explains a kind of generational evolution in the criticism of Modernist writing as it falls into the (near) past: “First come efforts to justify the whole. Then units of attention commence to get smaller, and yet remain always discrete, like gears and shafts. The penultimate unit is the single word; the ultimate is the very letter” (MM, 14).

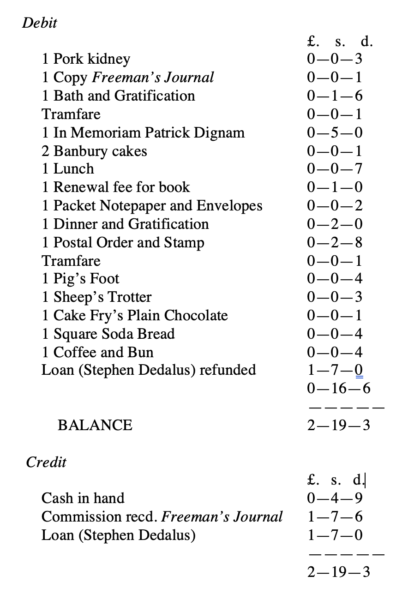

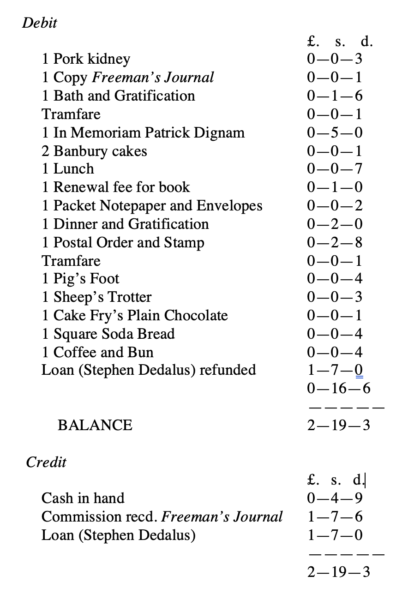

Kenner offers the history of critical readings of Joyce’s inclusion of Bloom’s budget in the “Ithaca” chapter of Ulysses as an example of the way that a Modernist’s actions may be most fully realized in the smallest of units (fig. 1). First, Kenner explains, it fell to a critic (Stuart Gilbert) to explain the nature of modernist narrative “as a whole”—to explain to those “accustomed to being told a story in the old way” why a novel might contain something so seemingly non-narrative and alienating as a budget in the first place (MM, 12).

But once this strange “inclusion” is accepted as a fully intended feature of the novel, rather than a mere “pedantic annoyance,” a critic (like Richard M. Kain) might move on to explain the role it played in the book’s design, furthering the narrative, coordinating individual entries with the book’s incidents. It would fall to Kenner’s hindsight to see the flabbergasting significance of the textual detail so small it was in fact not there: “It was two decades before someone (myself as it happened) noticed that the budget suppressed all record of the visit to Nighttown. Its most notable omission is the day’s largest disbursement (10s, left behind in the whorehouse). So it’s an edited budget, as it were for the eyes of Molly” (MM, 13). This interpretive rescue of what might seem a kind of continuity error, reconceiving an “accidental” omission as decisive “editing,” reveals something important about Joyce’s work as a novelist, about previously invisible places where decisions were being made. But more than that, it reveals something about the transformations that Modernism as an Era has wrought upon Joyce as an actor within it: “Even in Ithaca, the episode of stony fact, fact is manipulable, including numerical fact, the very atom of immutability” (MM, 13).

We might notice, though, that the closer Kenner gets to the workings of the work, the more ambivalent his account of its origins. What distinguishes Richard Kain’s justification of “the whole” from Kenner’s justification of texts at the atomic level is that the former can be referred to something like a structure of intention. For Kenner, the eloquent omission blinks back and forth between intended and determined. Nothing could be more assuredly referred to an authorial hand than these typed bits of numerical fact, the letters of which the words are made, the numbers that tally up income and expenditures. And yet at a distance of retrospect, these letters and numbers—and even the spaces where no letters and numbers are—seem to disclose something like the largest claims for the nature of transformed modernity, the state of affairs in which all facts and not just imagined facts are manipulable. It is not clear just how any individual author could have authored that fact. In Kenner’s account, the movement of the fingers is the way in which tiniest details come to disclose not so much an action as the tremendous power of the Era’s designs on us. The mismatch of scale between individual action and historical change makes it seem that it is forces beyond the self that uncomfortably jerk our little fingers around. Or as Stephen puts it in that same Nighttown visit: “Personally, I detest action. (He waves his hand.) Hand hurts me slightly.”6

This problem, I want to say, lies at the heart of Kenner’s “visit as method” and gives rise in his work to a series of indelible figures for the simultaneous elevation and occultation of artistic agency. Instead of Joyce’s Dublin,7 we have Dublin’s Joyce; or, as we are surely meant to hear it, Joyce’s Dublin’s Joyce. In The Pound Era we may hear a similar ambiguity about whether the “great man” is a cause or an effect. The Invisible Poet: T.S. Eliot is “invisible” in precisely this sense, and it is this uncertain oscillation between first and third person that gives Kenner’s writing its singular texture:

Let us assume that the impassive, stationary Man of Letters from whom the Collected Works are thought to emanate is a critical myth, the residuum of a hundred tangential guesses. Let us further assume (it is a convenient fiction: biography does not concern us) a man with certain talents and certain interests who wrote poems intermittently, never sure whether his gift was not on the point of exhaustion, and reviewed countless books because they were sent him for review and (for many years) he needed the money. Let us station him for some years in the Philosophy Department at Harvard, and allow weight to what passed through his mind there. Let us endow him with a mischievous intelligence, and set him to work reviewing for the Athenaeum. Let us simultaneously put him in touch with Ezra Pound, and make him, for good measure, the invisible assistant editor of The Egoist, which “ended with 185 subscribers and no newsstand or store sales”; all this in London, 1917, at the pivot of an age. Install him then, heavily camouflaged, in the very citadel of the Establishment, the Times Literary Supplement, where, protected by the massive unreality of his surroundings, a man who has mastered the idiom can deftly affirm fructive heresies about Donne and Marvell. Then let us consider the nature of what he wrote and published in those early years, examining as minutely as we like what we are under no compulsion to translate or “explain”: and then see whether the career subsequent to plays, Quartets, and celebrity does not assume intelligible contours. There has been no more instructive, more coherent, or more distinguished literary career in this century, all of it carried on in the full view of the public, with copious explanations at every stage; and the darkness did not comprehend it. Yet never comprehended, an American was awarded the Order of Merit and became England’s most honored man of letters, not in fulfilment of ambition but in recognition of qualities, real and valuable, which he had come to personify.8

Making Eliot intelligible, instructive, and coherent involves seeing him as a kind of personification of “values” particular to a place at “the pivot of an age.” Is this Eliot real? He is “a critical myth.” Is he a person? “Biography does not concern us.” The strange critical action of rendering Eliot retroactively legible involves being concerned with the facts that do not concern us under the correct description: “assuming” (for example) that much of Eliot’s writing emerged from a situation of economic uncertainty; noting that his mind was made what it was by being “stationed” in institutions where certain weighty ideas might “pass through” it; observing that his literary judgments were authoritative to the extent that he was “installed” within an “Establishment” that gave them authority. And yet something about the poet remains uncomprehended by these determinations, “camouflaged,” “in darkness,” “invisible”—or what could be the object of our interest? Kenner renders this paradox between the mind that is made and the mind that makes more concisely in describing the master work of the “most honored” poet: Kenner says of “The Waste Land,” “it is doubtful whether any other acknowledged masterpiece has been so heavily marked, with the author’s consent, by forces outside his control.”9

More than a clear account of Modernism, or a replicable method of criticism, Kenner’s visits with the great actors of modernist texts powerfully bequeath to us a problem of agency that emerges through attention to works of art.

In the remainder of this essay, I want briefly to lay out a kind of interest that I think the ambivalence within Kenner’s method makes visible, focusing on some of the most obviously intentional elements of the one of the most acknowledged master works of Modernism—and some of the least.

2. “What is this man doing?”

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

As just about everyone has noted, the most notable thing about the opening of “The Waste Land” is its striking enjambment. This a feature of style that Eliot was thinking about hard in the years leading up to the publication of the poem. In “Notes on the Blank Verse of Christopher Marlowe,” Eliot celebrated Marlowe’s central formal achievement as the contribution of a “deliberate and conscious workman,” distinguishable from the “pretty simple huffe-snuffe bombast” of his rhetoric. Specifically, he noted a new tonal range in Marlowe’s blank verse made possible by the aggressive enjambments of Tamburlaine: “a new driving power” achieved “by reinforcing the sentence period against the line period.”10

For Eliot, the effects of Marlowe’s of enjambment were two: intensity, and a new “conversational” style. In “The Waste Land,” “conversation” will arrive eight lines later with Countess Marie Larisch: “Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee / With a shower of rain.” Here, in the opening, Eliot goes all-in on intensity. The two periods of the opening stanza unfold as an intense experience of sentences “reinforced,” shored up against ruin; of grammaticality threatened but ultimately unbroken. One experiences the proximity of the threat of breakage because the sentences are driven over the edge of line periods into the rightward fall of present participial forms. Eliot, accelerating Marvell’s “driving” and multiplying his “reinforcing,” produces breeding, mixing, stirring, covering, feeding as objects of intense attention.

It isn’t quite enough to say, with Eliot, that in enjambment we find two compositional principles cutting “against” or competing with each other. We might also say that each system is sponsored by a different governing body. The grammaticality of “the sentence period” points to a national horizon of determination. For Eliot, the rules of sentence-making were administered by The King’s English, the 1906 precursor to H.W. Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Reviewing the latter in 1926, Eliot advocated a nightly session of disciplinary reinforcement: “every person who wishes to write ought to read in it (for it is inexhaustible) for a quarter of an hour every night before going to bed.”11

Metrical writing is also a subjection of individual expression to discipline. Vers Libre, as Eliot reminds us, is a “preposterous fiction.”12 Prosodic structures in English are broader than grammar’s national boundaries (“Even in the popular American magazines,” he sneers, “the lines are usually explicable in terms of prosody” [SP, 32]), but they are deeper as well. Their sanctioning body lives in that well of authoritative practice Eliot called “tradition,” offering a formal decorum that did not need to assert itself as “rule”—a “natural” regulative principle he did not hesitate to rhyme with social order altogether: “In an ideal state of society one might imagine the good New growing naturally out of the good Old, without the need for polemic and theory; this would be a society with a living tradition” (SP, 32).

Of the two transpersonal systems operating in the background here, the rules of grammar and the rules of meter, grammar seems perhaps the more powerful. It may be the case that for historical grammarian, “the history of languages shows that changes have constantly taken place in the past, and that what was bad grammar in one period may become good grammar in the next.”13 But there is no sentence Eliot can make that determines whether or not a sentence is grammatical in the present period, which is why someone who wishes to write good sentences should spend a quarter hour a night thinking of England and submitting to the King.

In contrast, although no vers is in practice libre, the thematics of the practice of versemaking is that of freedom. The opening line of “The Waste Land” leads off with a nine-syllable acephalous pentameter line. The second line counts the same nine syllables but counts them differently, as trochaic tetrameter with a dactylic second foot. We perceive this, if we do perceive it, because the rest of the stanza leans tetrameter, though with a trimeter thrown in in the fourth line for bad measure. The variability and instability of the opening proceeds as if to emphasize meter as a field of subjective decision made in relation to rules but not, as it were, strictly determined by them. If grammar works a little bit like a machine, meter feels more like a muse, sponsoring something like invention, autonomy, “life”: “It is this contrast between fixity and flux, this unperceived evasion of monotony, which is the very life of verse” (SP, 33).

This may be a distinction without a difference, or a difference in mood rather than a difference in fact. The evasion of monotony is surely to be celebrated, but it isn’t quite autonomy: “Vers libre … is a battle-cry of freedom, and there is no freedom in art” (SP, 32). But a difference in mood is a difference that is sought, and what is sought might be better found elsewhere. In “The Waste Land,” it is in the collision between grammar and meter, the superaddition of system upon system, of constraint against constraint, that we find a drama of individual action longed for through its overdetermined denials.

The effect of sentence driving past line, or line sawing through sentence, is to isolate the participial present tense form of the verb not so much from its subject, to which it is always firmly subordinated—we know it is April breeding, mixing, and stirring; it is Winter covering and feeding—as from its object. What does the act of “covering” cover? Only after the drop, we fall to “Earth.” What bounty does “feeding” feed? It is only after the end that its scope is confined to “a little life.”

A verb without an object is an action deprived of the context that delimits or constrains the field of its application or legibility. “Covering” without an “Earth,” or “Feeding” without a “life,” is, as Wittgenstein would never have said, an action without a world. He wouldn’t have said it because he would have regarded it as an impossibility; it is only the world (conceived as “all that is the case”), or the life, conceived as an ensemble of shared practices (“forms of life”), that make our actions actions. Eliot might seem, sometimes against his will, to agree: however much one might wish to assert the force or warmth of life (breeding, stirring, feeding), the (syntactically) determined arrival of “Earth” can only be (metrically) delayed, not denied.

Much of “The Waste Land” seems to turn on the drama of suffering this insight. The titles of the opening sections, for example, “The Burial of the Dead” and “A Game of Chess” name ways, perhaps rival ways, of conceptualizing the third-person horizons of legibility. The purpose of the Anglican liturgy of the burial of the dead is to render individual oblivion legible by decreeing both death and life to be communal property: “For none of us lives to himself/and none of us dies to himself.” And the purpose of the game of chess is to make oblivion unavailable by making it impossible. All moves, even loss, are a function of the rules; absence from the game just means you aren’t playing anymore. (In its inhuman efficiency at producing meaning out of small movements, a game might seem less restrictive than the section’s cancelled title, “IN THE CAGE.”) The Waste Land may be filled with suffering voices, persons victimized by shattered orders, but the poem seeks not freedom, but the redemptive forms of the collectivities without which they are nothing.

What could action without a world look like? Let us look, as Hugh Kenner has taught us to do, past the sentence to the mark; or past the beat to the strike.

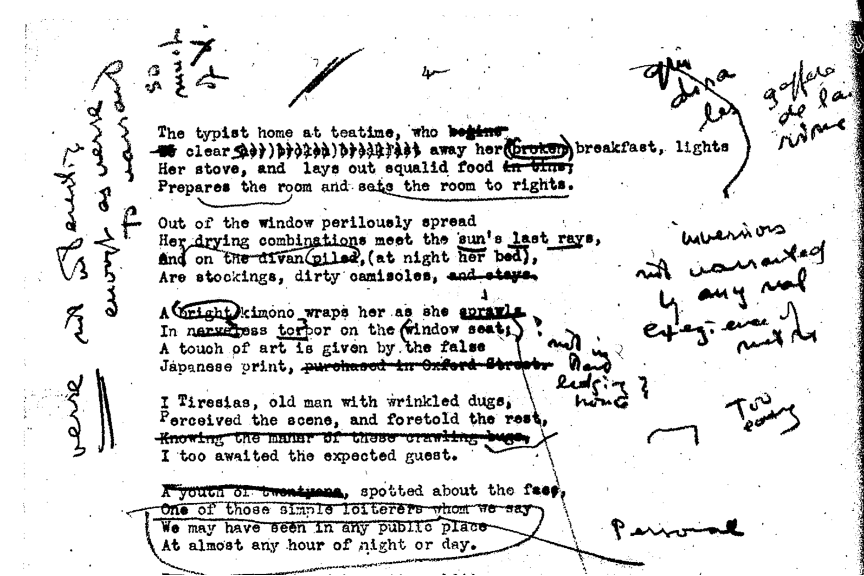

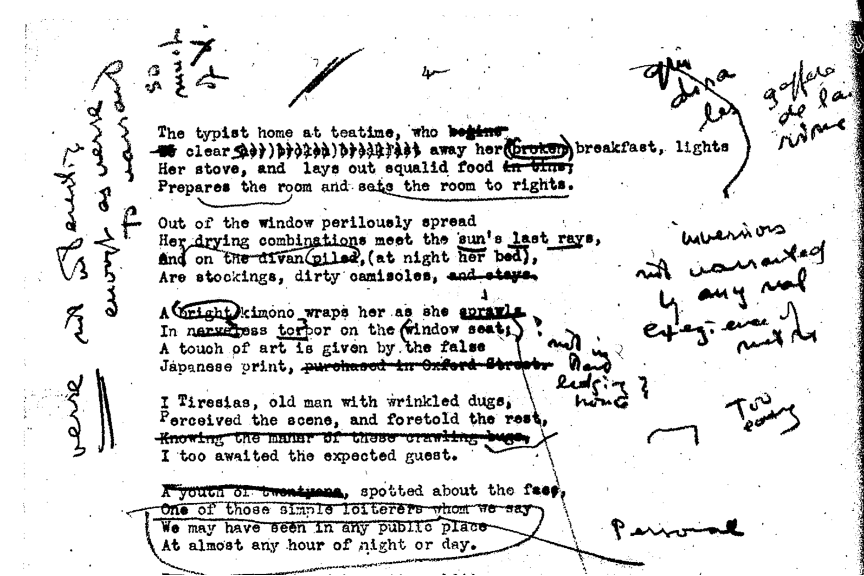

Here we can see “The Waste Land,” just as Kenner described it: “heavily marked, with the author’s consent, by forces outside his control” (fig. 2). Everywhere in the manuscripts, handwritten corrections point us outward into a social field of practice that render Eliot’s action of composing, of decisions and revisions, meaningful. Sometimes judgment is personified by Pound, who policed Eliot’s meters: “Too tum-pum at a stretch”; “too penty”; “Too loose.” Other judgments were given voice by Vivienne, who passed sentences, some of them to be included, (“What you get married for if you don’t want children?”) others to be excised (“The ivory men make company between us.”).14

Here, however, as almost nowhere else in the manuscripts, we can see a compositional decision made at some notional distance from the “uncontrolled” and external forces by which Eliot had no choice but to consent to be marked. Eliot, famously, composed on the typewriter, “The nearest approach to a manuscript I ever have is the first draft with pencil corrections.”15 Hugh Kenner was among the first critics to see this as a significant, even determining feature of the artist’s work.16 But it’s not quite, or not fully, true: In the second line of the poem we see the action of drafting—which is to say, the combination of invention, reconsideration, revision, and decision happening in something like real time. “The typist home at teatime, who begins / to clear her broken breakfast.” Stop: return; strike out with a sequence of close parentheses; retype: “away her broken breakfast. Lights”.

What is this man doing? What is the description of this action? Is Eliot making a metrical pattern? The question of whether or not “breakfast” should be accompanied by “broken”; isn’t not metrical; both because (by his own account) everything is metrical and also because fact the metrical intentionality of the line can be felt throughout its various preliminary versions: “to clear her broken breakfast, lights”, “clears away her broken breakfast.”, and, of course, in the final poem from which Broken is stricken:

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Is Eliot making sentences? The criteria of revision here absolutely are not not grammatical, since the elimination of an adjective is definitionally grammatical. But they also aren’t obviously “significantly” grammatical—which is to say, they are not obviously semantic: whether we see it or not; “broken” remains inside “breakfast” even when the adjective is eliminated.

What I want to say is that the drafts of the poem isolate here for our consideration an aspect of making a poem that we can see is a decisive action, but one that frustrates our ability to retroactively refer that action to a legible third person horizon of significance. As Eliot put it in his Paris Review interview, “in typing myself I make alterations, very considerable ones.”17 But what is considerable about the elimination and then reassertion of broken in relation breakfast? Eliot typing is an action in present participial form (let’s call it “making”)—whose object is not just delayed but withheld, that seems not easily situatable within the legible world of practices.

Typing, is, of course, as Kenner has already shown us, thinking of the deforming effects of the linotype machine on human action, an inauspicious place to find this kind of action: action that aspires to be meaningful but not to mean the world that determines what is meaningful. Thinking of imperatives that inflect behavior, we might compare the question of what it means that there is typing in “The Waste Land” to what we know, or think we know, about what it means that a typist is in “The Waste Land.” As Lawrence Rainey has argued in his exhaustive account of the poem’s composition, this is an aspect of the “The Waste Land” that is meaningful precisely as a “personification” of such freedom as is available within the horizons of the modern: “The typist was one of a family of figures who represented the promise of modern freedom: an allegedly new, autonomous subject whose appetites for pleasure and sensuous fulfillment were legitimated by modernity itself, by its promise that those new technologies, harnessed under systematic management, would ultimately enhance individual agency and create a richer life-world.”18 Typing is a type of action (technologized, systematic, managed) that makes an intended action (autonomous, agential, expressive) the limited thing that it is. To be a typist is to be the person for whom everything that is entailed in typing makes life what it is as well: a mere type of life, a little life. We might say something different but similar about the centrality of the figure of the typist to the recent debate about “Reading Eliot with the #MeToo Generation.” For Sumita Chakroborty, Eliot’s depiction of the typist is not even nominally concerned with the enhancement of agency, but rather with the violation of agency. But whether a typist is here because she is an ironized figure for technologically enabled “autonomy” or because she is an unwitting admission exacted through the poem of the patriarchally enforced determinations of modernity is, we might say, a difference in mood, rather than a difference in kind. To think of Eliot’s typing as meaningful in the way that his typist is meaningful is to refer typing to some horizon of action that can only be seen as a form of determination.

Would it be better from the perspective of art to think of Eliot’s parentheses as accidents? Would something like sheer contingency get us closer to what we mean by “autonomy?” Here, we might consider what we know about why “The Waste Land” was typed. As Eliot’s secretary tells us, Eliot’s habit of composing by machine resulted from an accident sustained as a young man: Eliot “strained one hand in rowing in a single shell while he was in the Harvard Graduate School and used a typewriter in preference to handwriting thereafter.”19 This might seem like an accident if anything is. But it does not strain the ingenuity to imagine a descendant of Hugh Kenner producing the third-person logic of even this sort of first-hand accident and the “preference” that follows from it: Eliot as he sculls is, as Kenner suggested, “stationed” in the philosophy department at Harvard University; “weighty ideas” from the philosophical tradition are being “passed through” his mind. A sociologically minded critic might well read the meaning of Eliot’s ideas as a function of his location, charting the elusive causal connections between the sculling hand, the typing hand, and the invisible hand, as mediated by an engulfing technology like the school.20

To speak telegraphically, for a moment, it is as if whole intelligence of our current critical moment is devoted toward reading the typing of a parenthesis as an action whose content can be retroactively filled in by powers beyond the self, much like the great parenthesis opened in “Little Gidding”:

(where every word is at home,

Taking its place to support the others,

The word neither diffident nor ostentatious,

An easy commerce of the old and the new,

The common word exact without vulgarity,

The formal word precise but not pedantic,

The complete consort dancing together)21

But in the parentheses in the manuscript of “The Waste Land,” which close without ever having opened, we find an action that we cannot read as a word “at home” in a “common” world. We cannot see this marking as bound by rules of grammar or meter, as typical of a kind of action, or as the allegorical decisions of a sociological type. Eliot’s typing is an action that points to the person, “typing myself,” whose conditions of legibility present us with a question.

Is it a question that we can abolish with a large enough lapse of time and large enough dose of critical ingenuity? Perhaps. But I would like to at least consider holding it open a while longer. Consider another canonical instance of a man at his task:

A man is pumping water into the cistern which supplies the drinking water of a house. Someone has found a way of systematically contaminating the source with a deadly cumulative poison whose effects are unnoticeable until they can no longer be cured. The house is regularly inhabited by a small group of party chiefs, with their immediate families, who are in control of a great state; they are engaged in exterminating the Jews and perhaps plan a world war. The man who contaminated the source has calculated that if these people are destroyed some good men will get into power who will govern well, or even institute the Kingdom of Heaven on earth and secure a good life for all the people; and he has revealed the calculation, together with the fact about the poison, to the man who is pumping. The death of the inhabitants of the house will, of course, have all sorts of other effects; e.g., that a number of people unknown to these men will receive legacies, about which they know nothing.

This man’s arm is going up and down, up and down. Certain muscles, with Latin names which doctors know, are contracting and relaxing. Certain substances are getting generated in some nerve fibres—substances whose generation in the course of voluntary movement interests physiologists. The moving arm is casting a shadow on a rockery where at one place and from one position it produces a curious effect as if a face were looking out of the rockery. Further, the pump makes a series of clicking noises, which are in fact beating out a noticeable rhythm.

Now we ask: what is this man doing? What is the description of his action?22

By asking “what is the description of his action,” Elizabeth Anscombe means something like: “what is the description of an action in terms of which all the other possible descriptions of an action make sense?”23 It is in the light of “the” description that we will be able to pick out all the other descriptions that we will agree to call intentional and to sort between the many possible descriptions of an intentional action (pumping, poisoning) from those descriptions that pick, out on the lower end, inconsequential accidents (the clicking sounds that fall into noticeable rhythm) and, on the upper end, consequential effects (the unknown persons in the future who receive transformative legacies as result of what I do).

But let me propose that to regard an action as poetic action is to adopt a distinctive attitude toward it. Regarding poetic action, we routinely fail to exclude apparent “byproducts,” like the clicking that emerges from our linguistic instrument beating out a noticeable rhythm. And we routinely extend a poet’s actions to engulf their apparent sequelae, like bequeathing legacies to unknown future persons. From an Anscombian perspective, such actions ought not to count as intentional, though they might come to pass. For Anscombe, prospective or retrospective reasons that count as intentional must be “practically salient from the first personal, practical perspective,”24 which is to say they depend on a sober English assessment of what we do or can do on this Earth and in this life. From that perspective, if one were to say in answer to the question, “why are you typing that parenthesis?”: “To bring about the Kingdom of God on earth,” you would not be offering a description of your action but a description of your delusion—even if the Kingdom of God were to come to pass, and your poem were to have played a part in its arrival. I want to say that what is at stake in regarding something as a poem is not quite the claim that this is a true description—that in making art, great men are making the future come into being. It is, rather, the claim that we do not know how to evaluate first person actions without measuring their legibility as determined by some third-person explanation, AND ALSO that we do not know how far our third-person understanding of actions might come to extend. Regarding “making a poem,” we are adopting a singular theoretical attitude toward the inflection of the little finger: we maintain the unity of intentional action all the way down, proposing that even the smallest “accidents” might be regarded as actions and extending the rationality of intentional relations all the way out—to encompass descriptions far past the sober consensus that would render what we do “salient.”

Thus, Eliot’s description of the poet’s work in his review essay, “The Metaphysical Poets,” offers an account of mental action that encompasses within intention events that would seem to belong to the accidental environment of making, like the noise of a typewriter:

When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man’s experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these two experiences have nothing to do with each other, or with the noise of the typewriter or the smell of cooking; in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes. (SP, 64)

And he juxtaposes this expanded category of the poet’s intention to an expanded category of the poets’ effect: “something … had happened to the mind of England between the time of Donne or Lord Herbert of Cherbury and the time of Tennyson and Browning; it is the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet” (SP, 64).

I want to say that this tradition of implausible explanations helps us to see why poetry might be a powerful place to think about the problem of historical change because poems seem like storehouses of precisely the kinds of action that are hard to see as already legible. They “elude foresight utterly” and are “occulted from most present sight.” They are a site of action in which the third-person category of meaningful action is encountered where it always and everywhere undertaken: in a resolutely first-person form. In poems, we turn the critic’s retrospective ingenuity in describing the meaning of past actions in the light of the world to which they belong into an attribution of intention. In doing this, however implausibly, we acknowledge something true: the future is, will be, has been, caused by the past. And we say something else that is true, but for which we have no adequate description: there will turn out to have been some causal relation between the actions of individuals acting on the basis of reasons they experience in the first-person, and the systems of understanding that make our actions retrospectively legible.

The lack of fit between the movement of the fingers, always undertaken by the poet, and the inflection point of an age, never quite produced by the poet, is what Kenner’s method allows us to visit. I’ll conclude by pointing to one more memorable instance of his descriptive texture, dwelling in the suggestive gap between inscrutable first-person action on the one hand and vast, inevitable, impersonal significance on the other, where the relation between the two is powerfully imputed but never quite arrives. It is in the one visit with Eliot that Kenner records at the heart of The Pound Era. The meeting took place at the Garrick club and places the poet’s careful, deliberate, and baffling manual manipulation of a piece of unidentified cheese alongside the implacable determinations of modernity experienced as impersonal fate:

He then took the Anonymous Cheese beneath his left hand, and the knife in his right hand, the thumb along the back of the blade as though to pare an apple. He then achieved with aplomb the impossible feat of peeling off a long slice. He ate this, attentively. He then transferred the Anonymous Cheese to the plate before him, and with no further memorable words proceeded without assistance to consume the entire Anonymous Cheese.

That was November 19, 1956. Joyce was dead, Lewis blind, Pound imprisoned; the author of The Waste Land not really changed, unless in the intensity of his preference for the anonymous.25

Eliot is resolutely, intensely present to Kenner: not dead, not blind, not imprisoned. He is moving his hands, expressing his preferences, in a way that will one day doubtless prove to be significant but that, in the present, can only look comical, pointless, inscrutable, anonymous, poetic. The extent that we take an interest in this action is the extent that we understand Eliot—and ourselves—as agents in history, as great actors who can be held responsible for acting meaningfully in ways whose legibility is not yet determined for us from the outside and in advance, but which will turn out of necessity to have been consequential. It will be as though we have made the future happen. Or, to put it differently, poetry is a place to entertain the inscrutable experience of seeming free.

Notes

1. Retrospect

Most retrospectives on Hugh Kenner’s career at some point mention the devoted thoroughness with which Kenner obeyed Ezra Pound’s injunction: “You have an obligation to visit the great men of your own time.”1 Kenner’s life-long devotion to Modernism springs out of the 1948 visit with Pound at St. Elizabeths in which the injunction was uttered—as does, perhaps, his magnum opus, The Pound Era. Other books surely sprang from other visits—with Samuel Beckett and Wyndham Lewis, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, and T.S. Eliot.

Indeed, Kenner seems to have elevated the visit into something like a method. Not without cause, Kenner’s Modernism has been understood as a celebration of the great man theory of modernism, of an artistic era shaped by close-up encounters with powerful imaginations and their consequential doings.

And yet there is another abiding interest in Kenner’s work: in the shaping force of technology and its influence on human action, and over the workings of the imagination. Kenner’s other master, also present at that fateful asylum visit, was the young English professor Marshall McLuhan, whose techno-determinism left its own imprint on Kenner’s work.

And so while the acknowledgements of the Pound Era begin with “Ezra Pound, to start with,”2 the dedication of his Mechanic Muse is “In Memoriam Etaoin Shrdlu.”3 Etaoin Shrdlu, as Kenner explains in the bravura opening of that 1987 book, was a frequent protagonist in the newspaper in the days of linotype setting; a nonce name the machine operator would enter to cancel a line to type after a mistake was made. Etaoin Shrdlu entered the news because the machine made the pathway for them to appear: composed of the 12 most frequently used letters in English, arrayed down the leftmost column of the linotype machine so they had the shortest distance to travel.4

In The Mechanic Muse, Kenner describes Modernism as a particular mode of accelerating technological transformation in which “every thinkable human activity save perhaps the reproductive was being mapped onto machinery” (MM, 7). It is, on the one hand, an era of “transparent technology”—in which the forming and deforming links and gears are visible to the eye. (The contrast is with the “screen-and-keyboard terminal” of postmodern technology, about which “your eye will tell you nothing” [MM, 10].) And yet what your eye tells you about modern technology is the curious and sometimes damaging unfitness for the hand that it is meant to extend and supplement, and the way that this lack of fit exercises an agency of its own. Kenner articulates this lack of fit as technology’s own principle: “the way to imitate a human activity is never to replicate the human action” (MM, 7).

Thus, the way a linotype machine works to replicate the activity of the skilled human compositor (creating a page of newsprint) does not involve replicating his actions—“picking letters up one by one and setting them in place”—rather, “matrices would slide down from magazines onto a moving belt for delivery onto the line’s incrementing array” (MM, 8). This mechanism had great advantages when it came to publishing newspapers, but it had deleterious effects on linotype operators. Due to an uncomfortable mismatch between machinic efficiency and human dexterity, the linotype operator has to make 51% of his keystrokes with his “left little finger” (MM, 5).

Modernism conceived this way is, distinctively, “those years, when human behavior, e.g. movements of one’s left little finger, could be inflected by imperatives one needn’t know about” (MM, 9). And those unknown imperatives produced, first and foremost, new forms of life, many of them disorienting and uncomfortable: crowd life, Fordist life, life coerced into clock-bound synchrony; and new forms of art that matter insofar as they orient us to these uncomfortable coercions and synchronizations.

These two different accounts of Modernism, defined on the one hand by powerful people and effective imaginations, and on the other by powerful imperatives that “engulf[ed] people” in their effectiveness (MM, 9), produce not just two accounts of art, but two different ways of understanding the critical task. A dedication to “Ezra Pound, to start with” might set you out on long journeys: to Venice, to wait for the doors of Santa Maria dei Miracoli to be unlocked “at the behest of three words” of the Cantos (“mermaids, that carving”). One visits to confirm that they are there, to see that they are as they have been described, and to affirm that their description tells you what you need to know about “how our epoch was extricated from the fin de siècle” by the work of great men: “I cannot but endorse the accuracy of perception that set in array the words that drew me on.”5

Whereas to “memorialize” Etoain Shrdlu is to retroactively acknowledge one’s determination by the impersonal mechanic forces that set things in array. Why retroactively? If the first of Kenner’s principles of technology described the non-mimetic, inhuman efficiency of action, the second describes the explanatory opacity that follows when inhuman powers determine the shape of human actions. Modernist technology makes actions, and specifically authorial actions, the sort of thing that are explicable, indeed detectable, as actions only in retrospect. What are the crucial features of Modernist writing? What is it that the artist makes, and where is the work of invention realized? In the Modernist text, explanation or interpretation will appear always as a kind of retrospective surprise: “the resulting pressures on human behavior are apt to elude foresight utterly, and be occulted from most present sight, to leave hindsight flabbergasted” (MM, 8).

For Kenner, the opacity of the relation between the occulted present and interpretive hindsight explains a kind of generational evolution in the criticism of Modernist writing as it falls into the (near) past: “First come efforts to justify the whole. Then units of attention commence to get smaller, and yet remain always discrete, like gears and shafts. The penultimate unit is the single word; the ultimate is the very letter” (MM, 14).

Kenner offers the history of critical readings of Joyce’s inclusion of Bloom’s budget in the “Ithaca” chapter of Ulysses as an example of the way that a Modernist’s actions may be most fully realized in the smallest of units (fig. 1). First, Kenner explains, it fell to a critic (Stuart Gilbert) to explain the nature of modernist narrative “as a whole”—to explain to those “accustomed to being told a story in the old way” why a novel might contain something so seemingly non-narrative and alienating as a budget in the first place (MM, 12).

But once this strange “inclusion” is accepted as a fully intended feature of the novel, rather than a mere “pedantic annoyance,” a critic (like Richard M. Kain) might move on to explain the role it played in the book’s design, furthering the narrative, coordinating individual entries with the book’s incidents. It would fall to Kenner’s hindsight to see the flabbergasting significance of the textual detail so small it was in fact not there: “It was two decades before someone (myself as it happened) noticed that the budget suppressed all record of the visit to Nighttown. Its most notable omission is the day’s largest disbursement (10s, left behind in the whorehouse). So it’s an edited budget, as it were for the eyes of Molly” (MM, 13). This interpretive rescue of what might seem a kind of continuity error, reconceiving an “accidental” omission as decisive “editing,” reveals something important about Joyce’s work as a novelist, about previously invisible places where decisions were being made. But more than that, it reveals something about the transformations that Modernism as an Era has wrought upon Joyce as an actor within it: “Even in Ithaca, the episode of stony fact, fact is manipulable, including numerical fact, the very atom of immutability” (MM, 13).

We might notice, though, that the closer Kenner gets to the workings of the work, the more ambivalent his account of its origins. What distinguishes Richard Kain’s justification of “the whole” from Kenner’s justification of texts at the atomic level is that the former can be referred to something like a structure of intention. For Kenner, the eloquent omission blinks back and forth between intended and determined. Nothing could be more assuredly referred to an authorial hand than these typed bits of numerical fact, the letters of which the words are made, the numbers that tally up income and expenditures. And yet at a distance of retrospect, these letters and numbers—and even the spaces where no letters and numbers are—seem to disclose something like the largest claims for the nature of transformed modernity, the state of affairs in which all facts and not just imagined facts are manipulable. It is not clear just how any individual author could have authored that fact. In Kenner’s account, the movement of the fingers is the way in which tiniest details come to disclose not so much an action as the tremendous power of the Era’s designs on us. The mismatch of scale between individual action and historical change makes it seem that it is forces beyond the self that uncomfortably jerk our little fingers around. Or as Stephen puts it in that same Nighttown visit: “Personally, I detest action. (He waves his hand.) Hand hurts me slightly.”6

This problem, I want to say, lies at the heart of Kenner’s “visit as method” and gives rise in his work to a series of indelible figures for the simultaneous elevation and occultation of artistic agency. Instead of Joyce’s Dublin,7 we have Dublin’s Joyce; or, as we are surely meant to hear it, Joyce’s Dublin’s Joyce. In The Pound Era we may hear a similar ambiguity about whether the “great man” is a cause or an effect. The Invisible Poet: T.S. Eliot is “invisible” in precisely this sense, and it is this uncertain oscillation between first and third person that gives Kenner’s writing its singular texture:

Let us assume that the impassive, stationary Man of Letters from whom the Collected Works are thought to emanate is a critical myth, the residuum of a hundred tangential guesses. Let us further assume (it is a convenient fiction: biography does not concern us) a man with certain talents and certain interests who wrote poems intermittently, never sure whether his gift was not on the point of exhaustion, and reviewed countless books because they were sent him for review and (for many years) he needed the money. Let us station him for some years in the Philosophy Department at Harvard, and allow weight to what passed through his mind there. Let us endow him with a mischievous intelligence, and set him to work reviewing for the Athenaeum. Let us simultaneously put him in touch with Ezra Pound, and make him, for good measure, the invisible assistant editor of The Egoist, which “ended with 185 subscribers and no newsstand or store sales”; all this in London, 1917, at the pivot of an age. Install him then, heavily camouflaged, in the very citadel of the Establishment, the Times Literary Supplement, where, protected by the massive unreality of his surroundings, a man who has mastered the idiom can deftly affirm fructive heresies about Donne and Marvell. Then let us consider the nature of what he wrote and published in those early years, examining as minutely as we like what we are under no compulsion to translate or “explain”: and then see whether the career subsequent to plays, Quartets, and celebrity does not assume intelligible contours. There has been no more instructive, more coherent, or more distinguished literary career in this century, all of it carried on in the full view of the public, with copious explanations at every stage; and the darkness did not comprehend it. Yet never comprehended, an American was awarded the Order of Merit and became England’s most honored man of letters, not in fulfilment of ambition but in recognition of qualities, real and valuable, which he had come to personify.8

Making Eliot intelligible, instructive, and coherent involves seeing him as a kind of personification of “values” particular to a place at “the pivot of an age.” Is this Eliot real? He is “a critical myth.” Is he a person? “Biography does not concern us.” The strange critical action of rendering Eliot retroactively legible involves being concerned with the facts that do not concern us under the correct description: “assuming” (for example) that much of Eliot’s writing emerged from a situation of economic uncertainty; noting that his mind was made what it was by being “stationed” in institutions where certain weighty ideas might “pass through” it; observing that his literary judgments were authoritative to the extent that he was “installed” within an “Establishment” that gave them authority. And yet something about the poet remains uncomprehended by these determinations, “camouflaged,” “in darkness,” “invisible”—or what could be the object of our interest? Kenner renders this paradox between the mind that is made and the mind that makes more concisely in describing the master work of the “most honored” poet: Kenner says of “The Waste Land,” “it is doubtful whether any other acknowledged masterpiece has been so heavily marked, with the author’s consent, by forces outside his control.”9

More than a clear account of Modernism, or a replicable method of criticism, Kenner’s visits with the great actors of modernist texts powerfully bequeath to us a problem of agency that emerges through attention to works of art.

In the remainder of this essay, I want briefly to lay out a kind of interest that I think the ambivalence within Kenner’s method makes visible, focusing on some of the most obviously intentional elements of the one of the most acknowledged master works of Modernism—and some of the least.

2. “What is this man doing?”

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

As just about everyone has noted, the most notable thing about the opening of “The Waste Land” is its striking enjambment. This a feature of style that Eliot was thinking about hard in the years leading up to the publication of the poem. In “Notes on the Blank Verse of Christopher Marlowe,” Eliot celebrated Marlowe’s central formal achievement as the contribution of a “deliberate and conscious workman,” distinguishable from the “pretty simple huffe-snuffe bombast” of his rhetoric. Specifically, he noted a new tonal range in Marlowe’s blank verse made possible by the aggressive enjambments of Tamburlaine: “a new driving power” achieved “by reinforcing the sentence period against the line period.”10

For Eliot, the effects of Marlowe’s of enjambment were two: intensity, and a new “conversational” style. In “The Waste Land,” “conversation” will arrive eight lines later with Countess Marie Larisch: “Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee / With a shower of rain.” Here, in the opening, Eliot goes all-in on intensity. The two periods of the opening stanza unfold as an intense experience of sentences “reinforced,” shored up against ruin; of grammaticality threatened but ultimately unbroken. One experiences the proximity of the threat of breakage because the sentences are driven over the edge of line periods into the rightward fall of present participial forms. Eliot, accelerating Marvell’s “driving” and multiplying his “reinforcing,” produces breeding, mixing, stirring, covering, feeding as objects of intense attention.

It isn’t quite enough to say, with Eliot, that in enjambment we find two compositional principles cutting “against” or competing with each other. We might also say that each system is sponsored by a different governing body. The grammaticality of “the sentence period” points to a national horizon of determination. For Eliot, the rules of sentence-making were administered by The King’s English, the 1906 precursor to H.W. Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Reviewing the latter in 1926, Eliot advocated a nightly session of disciplinary reinforcement: “every person who wishes to write ought to read in it (for it is inexhaustible) for a quarter of an hour every night before going to bed.”11

Metrical writing is also a subjection of individual expression to discipline. Vers Libre, as Eliot reminds us, is a “preposterous fiction.”12 Prosodic structures in English are broader than grammar’s national boundaries (“Even in the popular American magazines,” he sneers, “the lines are usually explicable in terms of prosody” [SP, 32]), but they are deeper as well. Their sanctioning body lives in that well of authoritative practice Eliot called “tradition,” offering a formal decorum that did not need to assert itself as “rule”—a “natural” regulative principle he did not hesitate to rhyme with social order altogether: “In an ideal state of society one might imagine the good New growing naturally out of the good Old, without the need for polemic and theory; this would be a society with a living tradition” (SP, 32).

Of the two transpersonal systems operating in the background here, the rules of grammar and the rules of meter, grammar seems perhaps the more powerful. It may be the case that for historical grammarian, “the history of languages shows that changes have constantly taken place in the past, and that what was bad grammar in one period may become good grammar in the next.”13 But there is no sentence Eliot can make that determines whether or not a sentence is grammatical in the present period, which is why someone who wishes to write good sentences should spend a quarter hour a night thinking of England and submitting to the King.

In contrast, although no vers is in practice libre, the thematics of the practice of versemaking is that of freedom. The opening line of “The Waste Land” leads off with a nine-syllable acephalous pentameter line. The second line counts the same nine syllables but counts them differently, as trochaic tetrameter with a dactylic second foot. We perceive this, if we do perceive it, because the rest of the stanza leans tetrameter, though with a trimeter thrown in in the fourth line for bad measure. The variability and instability of the opening proceeds as if to emphasize meter as a field of subjective decision made in relation to rules but not, as it were, strictly determined by them. If grammar works a little bit like a machine, meter feels more like a muse, sponsoring something like invention, autonomy, “life”: “It is this contrast between fixity and flux, this unperceived evasion of monotony, which is the very life of verse” (SP, 33).

This may be a distinction without a difference, or a difference in mood rather than a difference in fact. The evasion of monotony is surely to be celebrated, but it isn’t quite autonomy: “Vers libre … is a battle-cry of freedom, and there is no freedom in art” (SP, 32). But a difference in mood is a difference that is sought, and what is sought might be better found elsewhere. In “The Waste Land,” it is in the collision between grammar and meter, the superaddition of system upon system, of constraint against constraint, that we find a drama of individual action longed for through its overdetermined denials.

The effect of sentence driving past line, or line sawing through sentence, is to isolate the participial present tense form of the verb not so much from its subject, to which it is always firmly subordinated—we know it is April breeding, mixing, and stirring; it is Winter covering and feeding—as from its object. What does the act of “covering” cover? Only after the drop, we fall to “Earth.” What bounty does “feeding” feed? It is only after the end that its scope is confined to “a little life.”

A verb without an object is an action deprived of the context that delimits or constrains the field of its application or legibility. “Covering” without an “Earth,” or “Feeding” without a “life,” is, as Wittgenstein would never have said, an action without a world. He wouldn’t have said it because he would have regarded it as an impossibility; it is only the world (conceived as “all that is the case”), or the life, conceived as an ensemble of shared practices (“forms of life”), that make our actions actions. Eliot might seem, sometimes against his will, to agree: however much one might wish to assert the force or warmth of life (breeding, stirring, feeding), the (syntactically) determined arrival of “Earth” can only be (metrically) delayed, not denied.

Much of “The Waste Land” seems to turn on the drama of suffering this insight. The titles of the opening sections, for example, “The Burial of the Dead” and “A Game of Chess” name ways, perhaps rival ways, of conceptualizing the third-person horizons of legibility. The purpose of the Anglican liturgy of the burial of the dead is to render individual oblivion legible by decreeing both death and life to be communal property: “For none of us lives to himself/and none of us dies to himself.” And the purpose of the game of chess is to make oblivion unavailable by making it impossible. All moves, even loss, are a function of the rules; absence from the game just means you aren’t playing anymore. (In its inhuman efficiency at producing meaning out of small movements, a game might seem less restrictive than the section’s cancelled title, “IN THE CAGE.”) The Waste Land may be filled with suffering voices, persons victimized by shattered orders, but the poem seeks not freedom, but the redemptive forms of the collectivities without which they are nothing.

What could action without a world look like? Let us look, as Hugh Kenner has taught us to do, past the sentence to the mark; or past the beat to the strike.

Here we can see “The Waste Land,” just as Kenner described it: “heavily marked, with the author’s consent, by forces outside his control” (fig. 2). Everywhere in the manuscripts, handwritten corrections point us outward into a social field of practice that render Eliot’s action of composing, of decisions and revisions, meaningful. Sometimes judgment is personified by Pound, who policed Eliot’s meters: “Too tum-pum at a stretch”; “too penty”; “Too loose.” Other judgments were given voice by Vivienne, who passed sentences, some of them to be included, (“What you get married for if you don’t want children?”) others to be excised (“The ivory men make company between us.”).14

Here, however, as almost nowhere else in the manuscripts, we can see a compositional decision made at some notional distance from the “uncontrolled” and external forces by which Eliot had no choice but to consent to be marked. Eliot, famously, composed on the typewriter, “The nearest approach to a manuscript I ever have is the first draft with pencil corrections.”15 Hugh Kenner was among the first critics to see this as a significant, even determining feature of the artist’s work.16 But it’s not quite, or not fully, true: In the second line of the poem we see the action of drafting—which is to say, the combination of invention, reconsideration, revision, and decision happening in something like real time. “The typist home at teatime, who begins / to clear her broken breakfast.” Stop: return; strike out with a sequence of close parentheses; retype: “away her broken breakfast. Lights”.

What is this man doing? What is the description of this action? Is Eliot making a metrical pattern? The question of whether or not “breakfast” should be accompanied by “broken”; isn’t not metrical; both because (by his own account) everything is metrical and also because fact the metrical intentionality of the line can be felt throughout its various preliminary versions: “to clear her broken breakfast, lights”, “clears away her broken breakfast.”, and, of course, in the final poem from which Broken is stricken:

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Is Eliot making sentences? The criteria of revision here absolutely are not not grammatical, since the elimination of an adjective is definitionally grammatical. But they also aren’t obviously “significantly” grammatical—which is to say, they are not obviously semantic: whether we see it or not; “broken” remains inside “breakfast” even when the adjective is eliminated.

What I want to say is that the drafts of the poem isolate here for our consideration an aspect of making a poem that we can see is a decisive action, but one that frustrates our ability to retroactively refer that action to a legible third person horizon of significance. As Eliot put it in his Paris Review interview, “in typing myself I make alterations, very considerable ones.”17 But what is considerable about the elimination and then reassertion of broken in relation breakfast? Eliot typing is an action in present participial form (let’s call it “making”)—whose object is not just delayed but withheld, that seems not easily situatable within the legible world of practices.

Typing, is, of course, as Kenner has already shown us, thinking of the deforming effects of the linotype machine on human action, an inauspicious place to find this kind of action: action that aspires to be meaningful but not to mean the world that determines what is meaningful. Thinking of imperatives that inflect behavior, we might compare the question of what it means that there is typing in “The Waste Land” to what we know, or think we know, about what it means that a typist is in “The Waste Land.” As Lawrence Rainey has argued in his exhaustive account of the poem’s composition, this is an aspect of the “The Waste Land” that is meaningful precisely as a “personification” of such freedom as is available within the horizons of the modern: “The typist was one of a family of figures who represented the promise of modern freedom: an allegedly new, autonomous subject whose appetites for pleasure and sensuous fulfillment were legitimated by modernity itself, by its promise that those new technologies, harnessed under systematic management, would ultimately enhance individual agency and create a richer life-world.”18 Typing is a type of action (technologized, systematic, managed) that makes an intended action (autonomous, agential, expressive) the limited thing that it is. To be a typist is to be the person for whom everything that is entailed in typing makes life what it is as well: a mere type of life, a little life. We might say something different but similar about the centrality of the figure of the typist to the recent debate about “Reading Eliot with the #MeToo Generation.” For Sumita Chakroborty, Eliot’s depiction of the typist is not even nominally concerned with the enhancement of agency, but rather with the violation of agency. But whether a typist is here because she is an ironized figure for technologically enabled “autonomy” or because she is an unwitting admission exacted through the poem of the patriarchally enforced determinations of modernity is, we might say, a difference in mood, rather than a difference in kind. To think of Eliot’s typing as meaningful in the way that his typist is meaningful is to refer typing to some horizon of action that can only be seen as a form of determination.

Would it be better from the perspective of art to think of Eliot’s parentheses as accidents? Would something like sheer contingency get us closer to what we mean by “autonomy?” Here, we might consider what we know about why “The Waste Land” was typed. As Eliot’s secretary tells us, Eliot’s habit of composing by machine resulted from an accident sustained as a young man: Eliot “strained one hand in rowing in a single shell while he was in the Harvard Graduate School and used a typewriter in preference to handwriting thereafter.”19 This might seem like an accident if anything is. But it does not strain the ingenuity to imagine a descendant of Hugh Kenner producing the third-person logic of even this sort of first-hand accident and the “preference” that follows from it: Eliot as he sculls is, as Kenner suggested, “stationed” in the philosophy department at Harvard University; “weighty ideas” from the philosophical tradition are being “passed through” his mind. A sociologically minded critic might well read the meaning of Eliot’s ideas as a function of his location, charting the elusive causal connections between the sculling hand, the typing hand, and the invisible hand, as mediated by an engulfing technology like the school.20

To speak telegraphically, for a moment, it is as if whole intelligence of our current critical moment is devoted toward reading the typing of a parenthesis as an action whose content can be retroactively filled in by powers beyond the self, much like the great parenthesis opened in “Little Gidding”:

(where every word is at home,

Taking its place to support the others,

The word neither diffident nor ostentatious,

An easy commerce of the old and the new,

The common word exact without vulgarity,

The formal word precise but not pedantic,

The complete consort dancing together)21

But in the parentheses in the manuscript of “The Waste Land,” which close without ever having opened, we find an action that we cannot read as a word “at home” in a “common” world. We cannot see this marking as bound by rules of grammar or meter, as typical of a kind of action, or as the allegorical decisions of a sociological type. Eliot’s typing is an action that points to the person, “typing myself,” whose conditions of legibility present us with a question.

Is it a question that we can abolish with a large enough lapse of time and large enough dose of critical ingenuity? Perhaps. But I would like to at least consider holding it open a while longer. Consider another canonical instance of a man at his task:

A man is pumping water into the cistern which supplies the drinking water of a house. Someone has found a way of systematically contaminating the source with a deadly cumulative poison whose effects are unnoticeable until they can no longer be cured. The house is regularly inhabited by a small group of party chiefs, with their immediate families, who are in control of a great state; they are engaged in exterminating the Jews and perhaps plan a world war. The man who contaminated the source has calculated that if these people are destroyed some good men will get into power who will govern well, or even institute the Kingdom of Heaven on earth and secure a good life for all the people; and he has revealed the calculation, together with the fact about the poison, to the man who is pumping. The death of the inhabitants of the house will, of course, have all sorts of other effects; e.g., that a number of people unknown to these men will receive legacies, about which they know nothing.

This man’s arm is going up and down, up and down. Certain muscles, with Latin names which doctors know, are contracting and relaxing. Certain substances are getting generated in some nerve fibres—substances whose generation in the course of voluntary movement interests physiologists. The moving arm is casting a shadow on a rockery where at one place and from one position it produces a curious effect as if a face were looking out of the rockery. Further, the pump makes a series of clicking noises, which are in fact beating out a noticeable rhythm.

Now we ask: what is this man doing? What is the description of his action?22

By asking “what is the description of his action,” Elizabeth Anscombe means something like: “what is the description of an action in terms of which all the other possible descriptions of an action make sense?”23 It is in the light of “the” description that we will be able to pick out all the other descriptions that we will agree to call intentional and to sort between the many possible descriptions of an intentional action (pumping, poisoning) from those descriptions that pick, out on the lower end, inconsequential accidents (the clicking sounds that fall into noticeable rhythm) and, on the upper end, consequential effects (the unknown persons in the future who receive transformative legacies as result of what I do).

But let me propose that to regard an action as poetic action is to adopt a distinctive attitude toward it. Regarding poetic action, we routinely fail to exclude apparent “byproducts,” like the clicking that emerges from our linguistic instrument beating out a noticeable rhythm. And we routinely extend a poet’s actions to engulf their apparent sequelae, like bequeathing legacies to unknown future persons. From an Anscombian perspective, such actions ought not to count as intentional, though they might come to pass. For Anscombe, prospective or retrospective reasons that count as intentional must be “practically salient from the first personal, practical perspective,”24 which is to say they depend on a sober English assessment of what we do or can do on this Earth and in this life. From that perspective, if one were to say in answer to the question, “why are you typing that parenthesis?”: “To bring about the Kingdom of God on earth,” you would not be offering a description of your action but a description of your delusion—even if the Kingdom of God were to come to pass, and your poem were to have played a part in its arrival. I want to say that what is at stake in regarding something as a poem is not quite the claim that this is a true description—that in making art, great men are making the future come into being. It is, rather, the claim that we do not know how to evaluate first person actions without measuring their legibility as determined by some third-person explanation, AND ALSO that we do not know how far our third-person understanding of actions might come to extend. Regarding “making a poem,” we are adopting a singular theoretical attitude toward the inflection of the little finger: we maintain the unity of intentional action all the way down, proposing that even the smallest “accidents” might be regarded as actions and extending the rationality of intentional relations all the way out—to encompass descriptions far past the sober consensus that would render what we do “salient.”

Thus, Eliot’s description of the poet’s work in his review essay, “The Metaphysical Poets,” offers an account of mental action that encompasses within intention events that would seem to belong to the accidental environment of making, like the noise of a typewriter:

When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man’s experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these two experiences have nothing to do with each other, or with the noise of the typewriter or the smell of cooking; in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes. (SP, 64)

And he juxtaposes this expanded category of the poet’s intention to an expanded category of the poets’ effect: “something … had happened to the mind of England between the time of Donne or Lord Herbert of Cherbury and the time of Tennyson and Browning; it is the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet” (SP, 64).

I want to say that this tradition of implausible explanations helps us to see why poetry might be a powerful place to think about the problem of historical change because poems seem like storehouses of precisely the kinds of action that are hard to see as already legible. They “elude foresight utterly” and are “occulted from most present sight.” They are a site of action in which the third-person category of meaningful action is encountered where it always and everywhere undertaken: in a resolutely first-person form. In poems, we turn the critic’s retrospective ingenuity in describing the meaning of past actions in the light of the world to which they belong into an attribution of intention. In doing this, however implausibly, we acknowledge something true: the future is, will be, has been, caused by the past. And we say something else that is true, but for which we have no adequate description: there will turn out to have been some causal relation between the actions of individuals acting on the basis of reasons they experience in the first-person, and the systems of understanding that make our actions retrospectively legible.

The lack of fit between the movement of the fingers, always undertaken by the poet, and the inflection point of an age, never quite produced by the poet, is what Kenner’s method allows us to visit. I’ll conclude by pointing to one more memorable instance of his descriptive texture, dwelling in the suggestive gap between inscrutable first-person action on the one hand and vast, inevitable, impersonal significance on the other, where the relation between the two is powerfully imputed but never quite arrives. It is in the one visit with Eliot that Kenner records at the heart of The Pound Era. The meeting took place at the Garrick club and places the poet’s careful, deliberate, and baffling manual manipulation of a piece of unidentified cheese alongside the implacable determinations of modernity experienced as impersonal fate:

He then took the Anonymous Cheese beneath his left hand, and the knife in his right hand, the thumb along the back of the blade as though to pare an apple. He then achieved with aplomb the impossible feat of peeling off a long slice. He ate this, attentively. He then transferred the Anonymous Cheese to the plate before him, and with no further memorable words proceeded without assistance to consume the entire Anonymous Cheese.

That was November 19, 1956. Joyce was dead, Lewis blind, Pound imprisoned; the author of The Waste Land not really changed, unless in the intensity of his preference for the anonymous.25

Eliot is resolutely, intensely present to Kenner: not dead, not blind, not imprisoned. He is moving his hands, expressing his preferences, in a way that will one day doubtless prove to be significant but that, in the present, can only look comical, pointless, inscrutable, anonymous, poetic. The extent that we take an interest in this action is the extent that we understand Eliot—and ourselves—as agents in history, as great actors who can be held responsible for acting meaningfully in ways whose legibility is not yet determined for us from the outside and in advance, but which will turn out of necessity to have been consequential. It will be as though we have made the future happen. Or, to put it differently, poetry is a place to entertain the inscrutable experience of seeming free.

Notes