For his first solo show at Galleria Neon in 1989, the Italian Maurizio Cattelan locked the door and hung a sign that read, “Be back soon” (fig. 1).1 The artist was not back soon, however, and the gallery remained closed for the “show.” Four years later, for an exhibition at Galleria Massimo De Carlo, he repeated the gesture by bricking shut the front door. This time, the only object on display in the space, which was only visible through a gallery window, was a small mechanical toy teddy bear traversing the gallery by tightrope.2 Both of these early exhibitions reveal what would become a persistent quality in Cattelan’s art: his humorous ability to leverage art world and art institutional conventions in order to escape from physically making art.

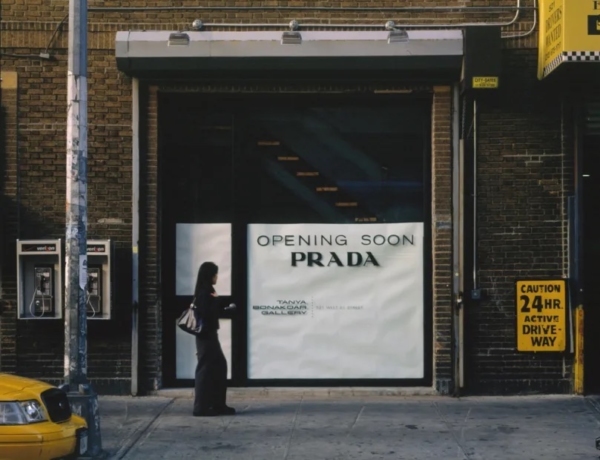

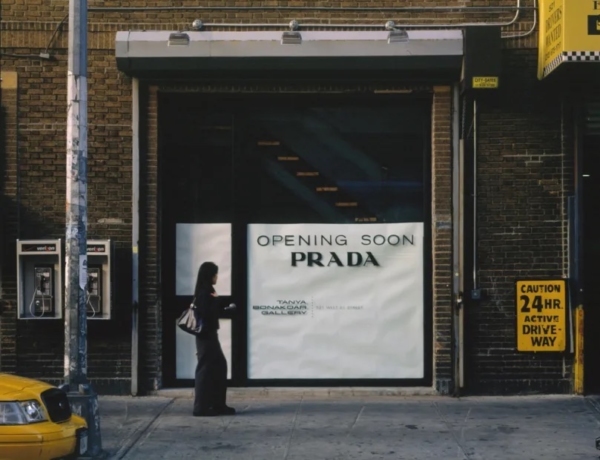

For these two shows in particular, the art historical convention that Cattelan employed was gallery blockage. In the 1990s and early 2000s, art gallery interruption became a recurring gesture among certain artists producing site-specific, institutionally-reflexive art. For an exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York in 2001, the duo Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset covered the gallery’s door and window with signage that read “Opening Soon: Prada.” The work did not explicitly prevent the public from entering the space, although that was the result (fig. 2).3 Two years later, as part of his 2003 contribution to the Spanish Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, Santiago Sierra sealed the pavilion entrance with cinder blocks, allowing only Spanish passport holders to enter the space via a back door. The number of similar projects in these years, when including artworks that effectively—if not literally—closed their exhibition spaces, is quite large. Mathieu Copeland and Balthazar Lovay attempted to compile a comprehensive list in 2017 with the monumental anthology The Anti-Museum and accompanying exhibition, “A Retrospective of Closed Exhibitions,” at Fri Art in Fribourg, Switzerland.4

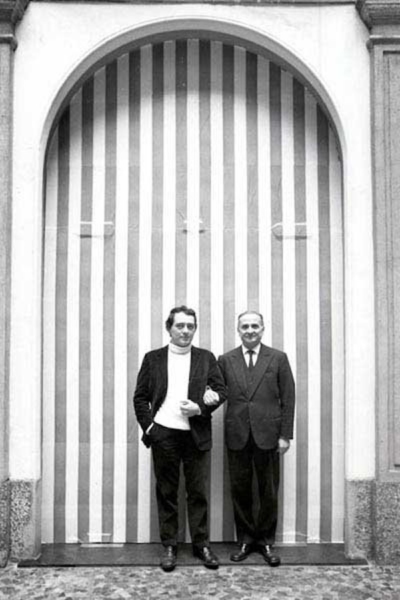

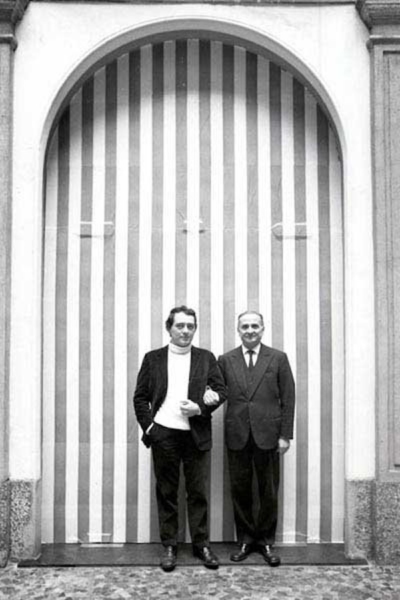

In form at least—that is, the form of closure—these projects reintroduced a practice of institutionally-critical Euro-Atlantic art from the 1960s. Daniel Buren’s first solo show, held at Galleria Apollinaire in Milan in 1968, featured the artist’s soon-to-be characteristic horizontal stripes blocking the gallery’s door (fig. 3).5 Robert Barry’s Closed Gallery Piece, a work that “traveled” to three galleries in 1969, consisted only of promotional announcements declaring that the galleries would be closed for the duration of the show.6 One of the galleries involved, Eugenia Butler in Los Angeles, was part of a small network of commercial spaces committed to conceptual work by American and European artists. This network also included Claire S. Copley Gallery (Los Angeles) where, five years later, Michael Asher removed a wall that divided the exhibition space from the back office for a project that simultaneously exhibited the gallery’s business operations while continuously interrupting them.7

Whatever tactical similarities Cattelan’s art shares with his predecessors, however, his redeployment of them was not a matter of institutional critique. For the Cattelan, the fact that gallery closure was both art historical and part of a contemporary zeitgeist made it a useful platform for mounting an escape from physical labor (from actually making art). Nancy Spector, in the exhibition catalogue for Cattelan’s Guggenheim retrospective in 2012, chronicled his gallery closures as part of a pattern of work refusal. “[F]or Cattelan, the gallery is not a space to mystify or demystify, it is merely a place of employment, which he approaches with the same rebellious attitude he would display toward any job” (MC 29). In an interview with the curator, Cattelan traced this talent for absenteeism to his youth in Italy. After he was fired from two different jobs (first at a laundry, then at the Church of Saint Anthony in Padua), he developed a scam:

I worked in a morgue, and I was fed up with it. I found a doctor who was willing to help me. In Italy, we have a system that if you are sick and can’t work, your company has to pay your salary anyway. Not bad. I was paying the doctor, and he was giving me days off. I took about six months off. (MC 32)

In his telling, the deception freed him from work at the morgue. But the tactic was not devoid of work altogether. In addition to bribing the doctor, Cattelan needed to be familiar enough with national-industrial entitlements programs that he could navigate them in his favor. My argument in this essay is that much of Cattelan’s claimed “escapes” from work (escapes that form a central tenant of his artistic practice) are not escapes at all. They are instead substitutions that translate the physical labor of art making into the bureaucratic labor of art making, and they do so via an expert deployment of accepted art institutional conventions (in the examples above, the convention of gallery closure). As his career developed over the 1990s, such bureaucratic labor would become more pointedly managerial in character. In this way, Cattelan’s art reflects and exaggerates a specific shift in both international capitalism and its critique that took place in the 1980s and 1990s—a shift to “creative” management practices as a hallmark of the “New Spirit” of international capitalism.

I borrow the term “New Spirit of Capitalism” from Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello’s book by the same title (1999), a text in which the authors articulate the historical development of capitalism through its integration of the critical positions of previous activist generations. With each new iteration, capitalism also develops a novel “spirit,” which describes both this integration of prior critique and the related set of justifications offered to workers to encourage their enthusiastic support for newly (or at least differently) exploitative working conditions. In the 1960s, the “second spirit of capitalism” was coming to an end. This spirit had long promoted itself to workers by offering “liberation from the specific alienation of the proletariat (its exploitation)” in the form of security. “[J]ob security and income from work were improved in exchange for working-class population settling, and the development of factory discipline.”8 In this way, the second spirit of capitalism integrated Marxist capitalist-critical positions (in regard to alienation) and sold itself to workers in late industrial Euro-America with the promise of increased stability as long as workers were willing to relinquish control over where they lived (i.e., in proximity to manufacturing centers), how they spent their labor time, and even how leisure and work time were divided.

In the 1960s, a new critique emerged from this second spirit—the “artistic critique”—aimed at the oppressiveness of centralized planning and its control over the shape and articulation of worker’s lives. “Demands for autonomy and self-fulfillment assumed the form given them by Parisian artists in the second half of the nineteenth century, who made uncertainty a lifestyle and a value” (NS 434). In the 1990s, the new spirit of capitalism integrated this artistic critique, and abandoned its offer of security and stability (unions, pensions, etc.), replacing it with labor oriented to “projects,” novelty, invention, and endless new beginnings. The authors find evidence for this shift in managerial texts, the kind of pseudo-scientific motivational and corporate structuring advice used by managers and business leaders to shape their organizations. Thus, the new spirit of capitalism was oriented, primarily, to encourage and facilitate the managerial classes, which became the exemplars of post-industrial, Euro-Atlantic capitalist labor.

But the effect of this liberalization for most workers was not liberation. Instead, increased “creativity” in the workplace translated into labor expectations that included constant reinvention and flexibility, insecure employment, endless job changes within and among companies and, eventually, erasure of the distinction between labor and leisure. The ramifications for the global economy have been tectonic: “unskilled jobs [are pushed] into less adventitious statutes, into subcontractors and/or insecure contracts” (NS 236) producing an abundance of precarious gig workers; sex discrimination creates new antagonisms between workers—where once women were excluded from the workforce, “Employers [now] use women’s search for part-time work to generalize underemployment contracts that subsequently become the norm in certain occupations” then “women suffer significant discrimination when it comes to being hired” (NS 240). As labor is destabilized it also becomes more intensive—workers are no longer paid by the day, they are paid by outcome, which means no breaks and no down time. It also means no on-the-job training, which was once the responsibly of companies and firms. Instead, training cost is incurred by individual workers (often in the form of student loan debt) or, in some countries, the state, which is now also responsible for the social costs of labor (healthcare, etc.). To be sure, this new spirit of capitalism has been a boon for some lucky individuals. Wages for top level managers and C-suite executives have never been higher, and their work often looks more like creative play than physical labor (think Elon Musk). But their labor experience is hardly the norm.

This transition from a 1960s artistic critique to 1990s creative labor maps loosely onto the gallery closure projects of the decades I describe above. In the 1960s, gallery closure emerged alongside a critique of the oppressive structure of the commercial art system, which had become a determining force of the creative labor of working artists. Asher recalls:

A critical analysis of the gallery structure was developed by a small number of artists in the late sixties and early seventies. … They believed that artists of previous generations had accepted uncritically … a distribution system (the gallery/market) which had often dictated the content and context of their work.9

The institutionally-critical tactics of this generation of post-minimalist artists had many targets—in Asher’s case, and, a few years later, in the work of Hans Haacke, those targets were primarily the systems of display and exchange codified in museums (note that “closure” in this time was primarily sited in commercial spaces). And in much of this work, artists were already imagining their labor as administrative if not managerial. Research and concept development overtook fabrication and production in these early post-minimalist practices. The transition from industrial to managerial capitalism as articulated by Boltanski and Chiapello was neither instantaneous nor absolute, especially in the realm of artmaking. Nevertheless, as deployed by this generation, the tactic of gallery closure was decidedly critical of the spaces it occupied.

By the 1990s, the shift in post-studio artistic labor from production to management was more profound—not only were artists generally in the habit of hiring assistants, but their project-based work looked more like conceptual labor, brainstorming, installation management, and oversight than like the manual labor of studio work. Thus, in the 1990s, closure work like that of Elmgreen and Dragset lost its critical edge in favor of a more complicit, or at least jocular, relationship with powerful institutions of art display and exchange. When asked about their relationship to the art market, for example, the duo once noted, “It’s like having a demanding and chronically unfaithful lover. Some say ‘Don’t bite the hand that feeds you,’ but biting can be pretty sexy.”10

Lane Relyea, a critic of this shift, describes these 1990s post-studio artists as of a kind with the “post-Fordist free agent and entrepreneur,”11 figures whose life and work have been entirely reconfigured by the promises of the New Spirit of Capitalism. However, in his analysis, artistic labor from the 1960s through the 2000s was threaded not only through the labor conventions of productive work, but also through the punk ethos of DIY culture, which emphasized self-reliance and individual management of all facets of production. (For example, a DIY magazine producer might be responsible for content, layout, design, printing, and distribution.) This ethos somewhat counterintuitively prefigured the transition from artistic-labor-as-object-production to artistic-labor-as-social-production. As it turns out, Cattelan’s artistic practice can be read through punk and hardcore DIY youth culture, too (more on this soon), although in the case of his early gallery closure projects, the transition from 1960s critique to 1990s capitalist spirit first appears quite simply and directly. In these projects, a closed exhibition space no longer evidences an artistic critique of the oppressive structures of the commercial gallery system. Rather, it amounts to a creative (or at least clever) displacement of physical art “work” by administrative labor (that is, in the examples of his closed exhibitions, Cattelan did not make any physical objects, but he did make administrative decisions with regard to signage and the deployment of historical and contemporary artistic idioms).

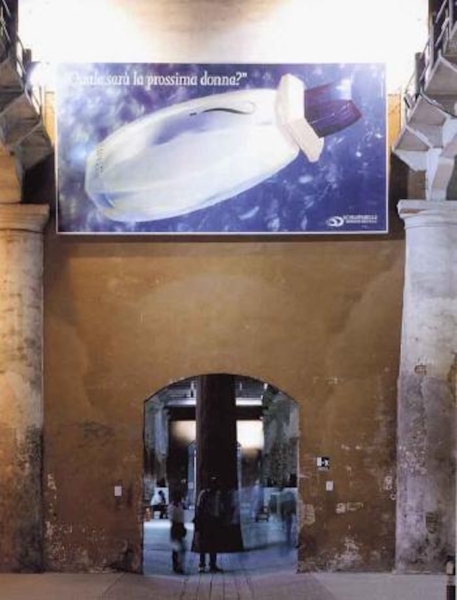

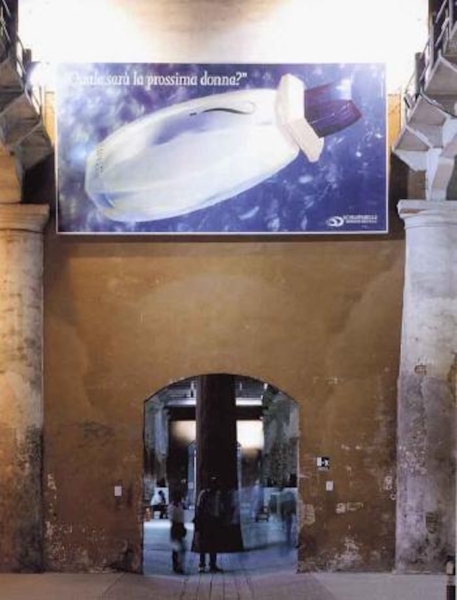

In these early projects, Cattelan’s artwork was certainly administrative, but it was not yet “creative management.” That changed in 1993, at the Venice Biennale, when the artist first successfully integrated his refusalist pragmatics with creative managerial labor (fig. 5). That year, Cattelan’s invitation to participate came with a central space for installation. The artist, in turn, leased the space to an advertising agency, which hung a billboard for a perfume (MC 195). As before, Cattelan was able to leverage conventions of art institutional practice (specifically the processes by which artists design and execute installation work for the central space at the Biennale) to escape from the work of physical artmaking. Here again, there are resonances between Cattelan’s single perfume billboard and the all-but-empty spaces of the “closed” galleries of his cohort of 1990s artists (recall that Elmgreen and Dragset’s closed gallery featured only a “coming soon” Prada sign). But now Cattelan also substituted the labor of middle-manager for the labor of creative producer. He effectively managed his Biennale space in order to turn a profit.

Through the lens of exhibition space closure alone, Cattelan’s escapist gestures read as little more than self-serving quotations of artistic practice. But if we trace Cattelan’s jokes to their roots in the soil of his Italian childhood, they offer evidence of how leftist sentiment is recruited into the spirit of capitalism. Indeed, the most provocative and most frustrating aspect of Cattelan’s art is how it models the integration of left-wing, intellectual, and worker anti-capitalist activism into the spirit of creative managerial capitalism broadly. His adept manipulations of art historical practice (which, to be sure, evidence a sophisticated understanding of not only the critical stakes of, in this case, early post-minimalist art, but also the legacy of administrative labor that contemporary art practice inherits) operate in allegorical relationship to capitalist-critical Italian intellectual history and its integration into labor conditions under Euro-Atlantic capitalism in the 1990s.

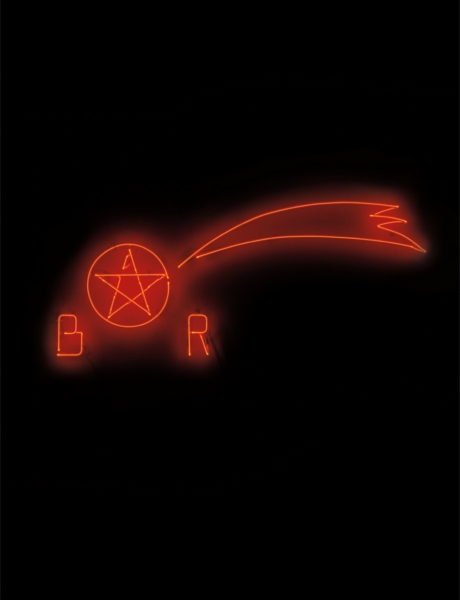

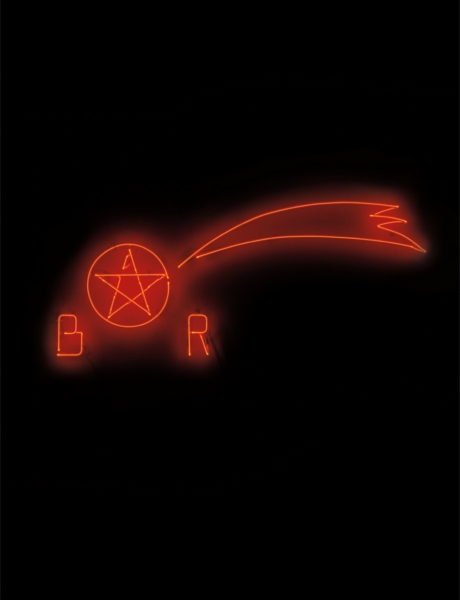

Cattelan titled his Biennale perfume project Working is a Bad Job, which is humorous, certainly, but also effects a subtle reformulation of Antonio Negri’s 1973 Potere Operaio pamphlet “Workers’ Party Against Work,” a Marxist-Leninist reading of the working class, value, and exploitation.12 The Marxist movements of 1960s and 70s Italy (Operaismo, Potere Operaio, and its later worker autonomy iteration, Autonomia Operaia) filter into Cattelan’s art in this way—humorously and subtly.13 Some of his earliest projects, including Christmas ’95 (1995) and Untitled (1996) détourne the iconic star symbol of the Red Brigades, a terrorist group affiliated with Workerist causes (fig. 7).14 In these artworks, Cattelan’s addition of a tail transforms the radical star symbol into a festive shooting star logo, which he then used as part of a Christmas nativity scene and an exhibition invitation card, respectively. In the case of Working is a Bad Job, Cattelan simply adapted Negri’s counterintuitive title and injected it with a blend of cynicism and cleverness. In the essay, Negri describes the evolution of the working class to a “level of productivity and ‘refinement of their talents’” that allows workers to “imagine their life not as work but as the absence of it, their activity as free and creative exercise” (BB 75). At the same time, he argues, the modern mass industrial worker has begun to unify and constitute itself “as a power that blows up the conditions of the production of surplus-value and that by means of the rule of value takes every mystified rationale away from capital’s domination.” The result, according to Negri, was an Italian working class increasingly able to refuse work in favor of appropriating its own surplus labor (BB 76–77).

What might this new working class look like, according to Negri? From the vantage of the 2020s, his conclusions are startling: “We are talking about the massive flight of productive labor from factory work toward the tertiary or service sectors” (BB 75). It is difficult today to imagine our precarious service sector, which includes low-paid fast food workers as well as middle-class managers, as liberated. But for Negri, this transition is a spontaneous move—an empowering move—precipitated by the working class that constitutes the possible origins of a new class consciousness. Negri’s analysis of postwar industrial capitalism is decidedly Marxist in orientation. Nevertheless, read through Boltanski and Chiapello’s account of capitalist evolution, Negri can be situated well within a broader, post-Marxist critique—what Boltanski and Chiapello call the “artistic critic”—of capitalism. Plainly, Negri’s polarizing of “work” and “free and creative exercise” suggests that, at least within the logic of this pamphlet, older movements for security and stability in work have been displaced by a new desire for freedom and creative expression from work. That freedom, according to Negri and, in turn, Cattelan, look like white collar and service work rather than productive factory (or studio) work.

Here is the lesson that Cattelan’s art has adapted from his Italian Workerist countrymen: by shifting the emphasis of his artistic work from studio labor to managerial labor he is able to claim an escape from “work.” To be sure, Cattelan’s art still requires labor, but under this paradigm it now requires the kind of creative administrative labor that was used in the 1990s to sell a new iteration of international capitalism to increasingly precarious workers. Like Negri’s mass worker, the contemporary artist has reached a level of productivity or “refinement of talent” that allows him to imagine art production not as physical labor but as “free and creative exercise.” However, he replaces Negri’s vision of a united working class freeing itself collectively from exploitive labor with a creative administrator promoting only himself for the sake of work refusal. The result is that Cattelan in fact generates an abundance of new kinds of flexible, creative work with each project, and not only for himself but for the many people (curators and other museum workers especially) that must deal with him. He effects this transition by leveraging what we might call the artist’s surplus labor—that is, the creative work in excess of the production of objects that transforms them into art. For Cattelan, this excess labor involves the appropriation of the conventions of art display. In the case of Working is a Bad Job, he simply repurposed the space of the Biennale in order to turn a perfume ad into an artwork (and, by extension, into an escape from the physical labor of object production).

However simple that gesture was in practice, the sited Working is a Bad Job had rather complex allegorical force. It was installed as part of the Venice Biennale, an international showcase that was originally conceived, in 1895, as a national showcase. Thus, the platform was already an appropriate venue for Cattelan to mark the integration of Italy-specific concerns into a Euro-Atlantic discourse. But not only was the work part of the Venice Biennale, it was installed as part of Aperto ’93, a rhizomatic group show unaffiliated with any single nation (that is, distinct from the national showcases of the Venice Pavilions). Aperto ’93 (Open ’93) took place in the Corderie building of the Arsenale, and thus relatively far from the national Pavilions. The show was conceived as a reformulation of Aperto (1980), a sideshow of young artists that was inaugurated by Achille Bonito Oliva and Harald Szeemann. In 1993, Bonito Oliva was now the artistic director of the entire Venice Biennale, and in his reformulation, the new Aperto was to showcase young curators rather than young artists (evidence of a shift from productive to administrative creative labor within the logic of the Biennale as a whole).

The 45th Venice Biennale marked a significant moment in the history of the festival, which was under pressure from an Italy in decline and waning interest in the “national art” model of the event. Clarissa Ricci has described the pressures on, and significance of, the 1993 festival in detail in “Towards a Contemporary Venice Biennale:”

The devaluation of the Lira in 1992 caused the temporary withdrawal of Italy from the European Monetary System (EMS). The consequences of increased taxation, together with policies to curb public spending, was accompanied by corruption scandals known as “Tangentopoli” (Bribesville), and together this caused the First Italian Republic to collapse. While this epochal shift was occurring, the Biennale was losing its international impact. Its national pavilions were viewed by some as anachronistic and visitor numbers had dropped.15

Bonito Oliva was tasked with transforming the Biennale into a truly global art event, and he did so through recourse to an “open,” distributed structure, geographically-diverse content (Chinese artists were included in the 1993 show for the first time), and a turn to an expanding field of creative practice. Within the logic of the Biennale, that meant a total of fifteen different curated exhibitions, including Aperto ’93, which featured its own thirteen interconnected curatorial projects on the theme of the “emerging” global economic/cultural paradigm, educational programming (including a school for curators in partnership with École du Magasin), and an overwhelming (to many viewers) abundance of projects and ancillary events. As Ricci describes them, “[A] conference [on the “Production, Circulation, and Conservation of Artworks”] and the school for curators were part of a larger educational project that was meant to be the backbone of the Biennale’s permanent activities. [This larger educational project], which was only partially realised, also comprised events and shows throughout the exhibition’s duration.”16

These events—which cost much more than the Biennale’s budget—were paid for by Bonito Oliva’s aggressive fundraising campaign and were thus “powered by the intellectual and managerial energies of Venetian entrepreneurs.” In short, the faltering Venice Biennale model was, in 1993, given new life by an artistic director whose plan celebrated curatorial work and the far-reaching administrative labor of conference and event planning. It was, in a word, the first truly “neoliberal” Venice Biennale.17 And it was there, in Cattelan’s home country of Italy, in the Arsenale, as part of an “open” curatorial showcase, funded, as it was, by Italian entrepreneurs, that Cattelan refused work by renting out his gallery space in order to make some additional money.

Born in 1960, Cattelan would have been too young to participate in Northern Italy’s early Workerist movements, even if his home city was a locus for some of its main branches.18 Negri, who was also born in Padua and taught at the University of Padua beginning in the late 1950s, was one of the founders of Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power), an affiliation of labor groups and activists committed to a Marxist reading of Italian industrialization. Cattelan came of age a decade later in the midst of the region’s “Years of Lead,” a time of violent confrontations among the radical left, the fascist right, and the police, which resulted in widespread fear of both terrorism and incarceration. Padua was a central city in these years, the site of the first murders committed by the Red Brigades. Around this time, in the mid-1970s, cynicism and irony began to creep into Workerist projects as younger workers and students joined the cause. Bologna’s student movement in 1977, for example, which remained worker-centric but came to include university students, small shop workers, feminists, precarious workers, and social misfits, often made use of humorous or defeatist slogans. (For example, “Gui e Tanassi sono intelligenti, siamo noi i veri deficenti” [“Gui and Tanassi are smart, we are the real morons”], which refers to Italian politicians who were accused of taking bribes from Lockheed Martin in the mid 1970s.)19

A much more aggressive cynicism arrived in Italy with the hardcore punk youth culture of the following decade. Bands like Raw Power (whose name bears a passing resemblance to Potere Operaio), The Wretched, I Refuse It! and RAF20 adopted the bombastic language of Italian worker activism and blended it with the angry, though also often ironic, nihilism of punk’s “No Future” ideology.21 Autonomia Operaia had a significant influence on the attitudes and style of address of these Italian punks, especially in the early years. In an interview for the 2015 documentary Italian Punk Hardcore 1980–1989: The Movie, Stefano Bettini, singer for I Refuse It! describes the scene’s origins:

During the early years, back in like ’77, … I was 15–18 years old, but I believed that it was normal for people my age to participate in the autonomy movement. Then, all those things from England came out: the Sex Pistols were the first.22

Like punk movements elsewhere, influences in Italy arrived piecemeal from English-speaking countries—first the U.K., then the U.S. This wave of anarcho-cynicism merged with the falling tide of Italian Workerism.

For bands like Peggio Punx, who initially had more interest in social and political antagonism than music making, humor became a key part of a project of cynical social refusal. According to its members, the band started as a practical joke:

We had the idea of pulling a hoax in the same way as the Sex Pistols’ “Great Rock n’ Roll Swindle.” We wanted to create a lot of hype for a band by filling the city with graffiti and fliers, and so we did. We wanted to set up a fake gig, collect the money, and then flee.23

These were Cattelan’s compatriots—working class, angry, and alienated—and their cynicism was of a kind with his. Cattelan’s career would be bolstered by a project similar to Peggio Punx’s hoax. For his 1992 Oblomov Foundation he petitioned 100 people for $100 donations to a scholarship—$10,000 in total—that would allow the winning artist to abstain from showing work for one year (fig. 8). According to Cattelan, in the end, no artist would accept the award for fear of damaging his or her career, and so he used the money to move to New York City.24 For both Peggio Punx and Cattelan, the scam turned on their ability to leverage the conventions of their art and its funding and promotion. For Peggio Punx, these conventions included promotional vandalism, Xerox fliers, and ticket sales. Cattelan’s scam leveraged the conventions of international art awards, foundations, and the tradition of charitable giving.

Here is the revelation of Cattelan’s work, because whatever origins his practice had in working-class Italian sentiment, his professional career has been characterized exclusively by creative administrative practices. This shift is most evident at the level of absenteeism. Where many of Cattelan’s artistic punchlines suggest that the artist has weaseled out of “work” (i.e., Working is a Bad Job), in fact, the artist has merely substituted the labor of creative administration for the labor of production. In the case of the Oblomov Foundation, Cattelan’s claim that the funds were designed to facilitate a break from work is undermined by the fact that the money was generated by his own sustained managerial labor (mostly raising capital via networking). Because Cattelan’s work is in direct conversation with the Workerist roots of his native Padua—a conversation he invokes not only through his interest in absenteeism but also by his overt use of the Red Brigades’ symbol—his turn is not just humorous (as so many critics suggest), it is aggressively cynical. More cynical, indeed, than the hardcore punks who preceded him, because while their angry refusal offered a DIY and often rather selfish rereading of Workerist refusal, their projects were still largely hostile to the functioning of international capitalism and, individually, most of the bands were resistant to anything like “selling out.” Cattelan’s work, on the contrary, is all about selling. His art exploits the fact that the Marxist artistic critique of industrial labor fomented in his hometown has been fully integrated into postindustrial managerial capitalism. Cattelan is thus the new “creative” Company Man, an artist who has embraced the promotional message used to sell this new spirit of capitalism: that freedom from work comes in the form of flexible, entrepreneurial management (which, in this new formulation, is not “work”).

Cattelan took this message with him to America (funded, as he was, by the Oblomov scam), where he honed his administrative “escape” from work. In 1995, a few years after his arrival, he and curator Jade Dellinger hatched a plan to use university funds to pay for a touristic vacation to Florida. Dellinger had been developing his own parasitic exhibition program within the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) for years. Under the series title Use as Directed, these smaller interventions were slipped into CAM’s regular programing every several months without the need for space or support (aside from a nominal stipend of $1,000 from the university). Dellinger invited Cattelan to pitch a project for the series, which eventually became Choose Your Destination: How to Get a Museum-Paid Vacation. The conceit was simple: Cattelan and Dellinger used the $1,000 stipend to pay for Cattelan’s flight to Florida and for tickets to the state’s amusement parks. The collaborators stayed (for free) at the home of Dellinger’s parents and used their car for transportation. They then documented their travels with souvenir snapshots at parks and beaches, including Busch Gardens and Disney World, and with a small series of novelty caricatures.25

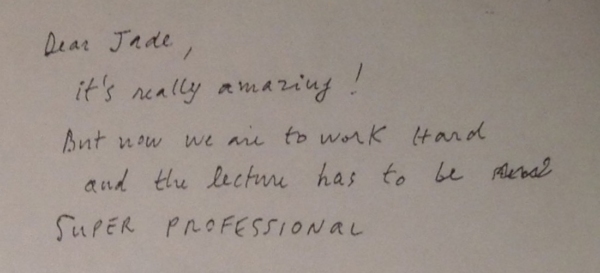

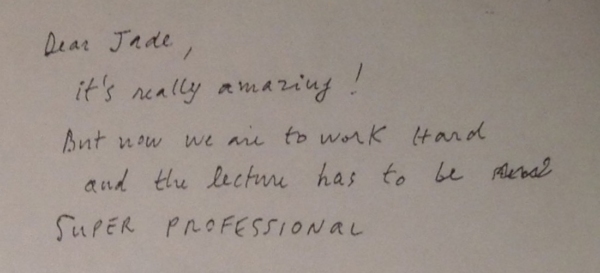

In Cattelan’s titular formulation, the project was something of a scam—a manipulation in which the artist demonstrates how to trick a museum into paying for a vacation. But in practice the “vacation” was exhausting. Their days were filled with touristic events designed to produce a body of documentary images, they made a limited-edition invitation card (out of a détourned found Florida postcard), and in the end the artist and curator gave a public lecture at the museum. As Cattelan admitted in early faxed correspondence to Dellinger, “we are to work hard and the lecture has to be SUPER PROFESSIONAL” (fig. 9).26 The fact that the artists corresponded via fax machine evidences the project’s white-collar sympathies, as does the claim to professionalism. And the reference to hard work underscores the fact that the vacation was not much of an escape from labor but rather a labor translation.

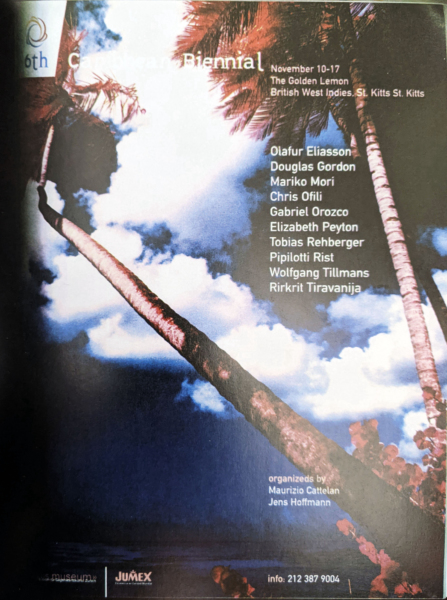

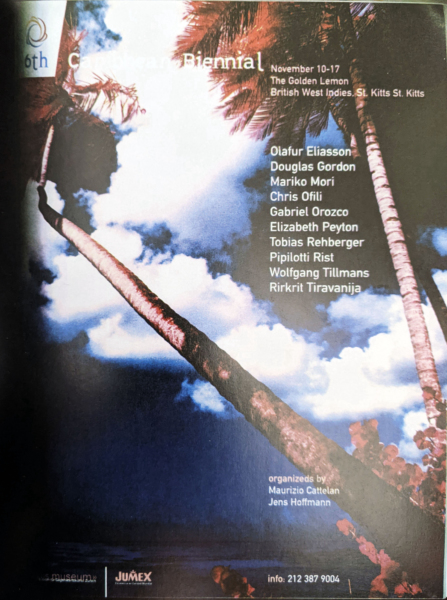

Choose Your Destination served as a template for what would become one of Cattelan’s most famous art events, the 6th Caribbean Biennial. In 1999, Cattelan and curator Jens Hoffmann mounted a promotional campaign for a non-existent international art festival and corresponding non-existent exhibition. According to their advertisements, which appeared in the art-world publications Artforum, Frieze, and Flash Art, this fictional exhibition was to feature work by Vanessa Beecroft, Olafur Eliasson, and Rirkrit Tiravanija, among others—all regular fixtures of the international biennial system (fig. 10).27 But as the artist and curator imagined it, the “Biennial” was actually an excuse for the invited artists to take a sponsored trip to the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, which they documented as a retreat from the art world. Again, like Peggio Punx, Cattelan used the promotional apparatus of his discipline to fund an escape. The hotel stay was covered by a wealthy collector, and the project on the whole had corporate sponsorship from the Migros Museum and the Jumex juice brand.28 Moreover, his incorporation of brand-named biennial regulars allowed him to hijack the rapidly proliferating format of the international mega exhibition—that is, he was able to leverage these names to attract sponsorship. But it is precisely because of such manipulations that the event was not at all devoid of labor. As Cattelan acknowledged, “Putting together a show in a few months, gathering all those artists in one place is something that requires as much strength and concentration as painting the biggest canvas” (CB). As far as free vacations go, the Biennial was a lot of work.

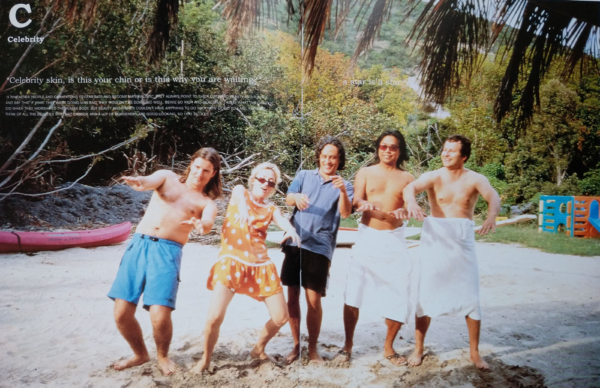

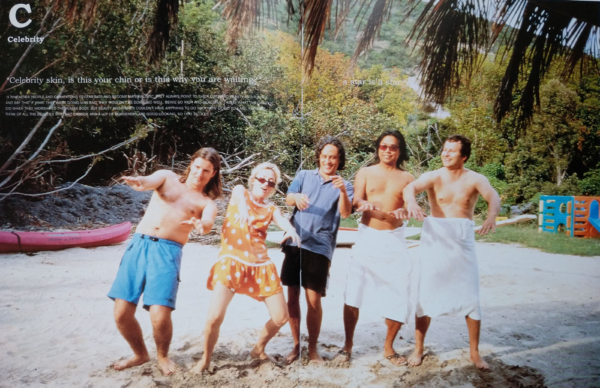

Cattelan’s quotation comes from an exhibition catalogue that was produced after the Biennial, a document of the trip that takes the form of an ABC reader for navigating the new managerial labor of art display and exchange. The book includes meditations on everything from Advertising to Xenophobia—phenomena one might encounter in the increasingly global-capitalist biennial art world. Even the exhibition catalogue format is taken as an object of inquiry: the entry for “C” includes “Colophon” and the book’s own colophon. The “C” section also includes “Celebrity,” and this is indeed an operative term in Cattelan’s artistic lexicon. Among the many “bad boy” artist personae today, Cattelan is one of the best known, precisely because of well-publicized scams like the fictional Caribbean biennial. It was with this project in particular that Cattelan embraced the phenomenon of art world celebrity as an artistic device that could be manipulated in order to stage an escape from physical labor.

The entry for “Celebrity” includes a quotation on success and materialism adapted from Andy Warhol’s ABC book of aphorisms, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (1975)—although the quotation is incorrect. It reads: “Whenever people and civilizations degenerate and become materialistic, they always point to their outward beauty and riches and say that if what they were doing was bad, they wouldn’t be doing so well” (fig. 11).29 Cattelan’s slight misrepresentation of Warhol points to another incongruity: where Warhol’s quotation comes from a “B” section on “Beauty,” Cattelan has adapted it to his section “C” on Celebrity. In the catalogue chapter, the unattributed quotation appears overtop of an image of some of the key art world celebrities who participated in the Biennial: Eliasson, Pipilotti Rist, Gabriel Orozco, Tiravanija, and Tobias Rehberger appear in mock-hula pose on a Caribbean beach. They compose exactly half of the list of artists named on the Biennial promotional advertisements, indicating, within the logic of the project and its promotion, a direct correlation between instrumentalized Warholian artistic celebrity and Cattelan’s ability to fake a biennial.

Relyea’s discussion of 1990s artistic labor is again instructive here because he describes the relationship between punk DIY culture and turn-of-the-century phenomena of self-production and self-promotion.30 In his account, much of the “global” and biennial artworld has embraced the social sphere (drinks, apartment hangs, communal dinners) as the primary context of artistic intervention. At the center of this turn to sociability is an artistic investment in the social actor—the self:

[T]oday’s network paradigm lends itself to a neoentrepreneurial mythology about volunteerism and “do it yourself” (DIY) agency. “In a world regarded as extremely uncertain and fluctuating,” Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello write … “the self is the only element worth the effort of identifying and developing, since it is the only thing that presents itself as even minimally enduring.”31

Relyea’s account of self-investment (made via Boltanski and Chiapello) resonates with a much earlier observation by Michel Foucault on the nature of productive labor under neoliberal capitalism. In his 1979 lecture on American neoliberalism, Foucault describes the new laboring subject as an “entrepreneur of himself”:

Neo-liberalism appears … as a return to homo œconomicus. This is true, but … with a considerable shift, since what is homo œconomicus, economic man, in the classical conception? … The characteristic feature of the classical conception of homo œconomicus is the partner of exchange and the theory of utility based on a problematic of needs.

In neo-liberalism—and it does not hide this; it proclaims it—there is also a theory of homo œconomicus, but he is not at all a partner of exchange. Homo œconomicus is an entrepreneur, an entrepreneur of himself. … being for himself his own capital, being for himself his own producer.32

Somewhere between these self-productive positions—between the DIY self-investment of The New Spirit of Capitalism and Foucault’s neoliberal homo œconomicus, we find Cattelan’s creative manager. What Cattelan’s art reveals is that the promise of the new spirit, the promise that industrial productive labor would give way to a liberated management labor in a service economy (this, again, is the evolution of the working class that Negri describes), was, in practice, a command that all aspects of one’s life—all work, all play—be transformed into the productive labor of self-investment (of self-management). Thus, ultimately in Cattelan’s art, “management” is not just the service labor of administration, it is also the labor of perpetual self-production—a labor that the Euro-Atlantic economy demands of all its subjects.

We find evidence of this fact interspersed throughout the Caribbean Biennial catalogue’s small lessons on art in the age of Euro-Atlantic capitalism, often under the guise of promises like “freedom.” Here Cattelan is most explicit about his work’s proximity to the “artistic critique” of postwar industrial capitalism and its complicity with this new spirit of managerial labor. Under “F: Fame—Freedom—Failure” he writes, “Freedom is nothing other than the possibility of establishing various interconnections between individuals, projects, organizations, services.” It is nothing more, in other words, than management. Under “I,” in an interview with Biennial conspirators Hoffman and Massimiliano Gioni, he claims that the artist’s role is not really about making things anyway. “[T]he role of the artist is much more corrupted than we like to think: he is never an innocent creator, detached from practical issues. In a way he is already a curator, of his own image at least. And he deals daily with problems that curators are familiar with: finding money, developing a concept for a show, getting someone to write a good piece for a catalogue.” In all, the catalogue for the 6th Caribbean Biennial reads like the kind of management literature that Boltanski and Chiapello analyzed for their account of the new spirit of capitalism—and in Cattelan’s handling, management is just about anything, from “curating” his own image to subcontracting catalogue authors (hence his book is organized as a comprehensive manual from A to Z).

As far as I can tell from his various statements, artwork titles, and scams, the well-crafted Cattelan artist-persona is not at all upset by these new demands for endless self-production. On the contrary, his writing suggests that he has entirely internalized international capitalism’s demands—he’s rather good at satisfying them, after all. “What I’m really interested in,” he tells his conspirators Hoffman and Gioni, “is this notion of complexity, the idea that there are no fixed roles and definitions. Everyone is forced to change roles every single moment of his life” (CB). The assertion resonates with Pierre Bourdieu’s early analysis of neoliberal labor: “The absolute reign of flexibility is established, with employees being hired on fixed-term contracts or on a temporary basis [with] repeated corporate restructurings and, within the firm itself, competition among autonomous divisions as well as among teams forced to perform multiple functions.”33 Gilles Deleuze, articulating in 1990 what he understands to be the shift from Foucault’s “disciplinary society” to the neoliberal “society of control,” came to a similar conclusion about labor under neoliberal capitalism:

In the disciplinary societies one was always starting again (from school to the barracks, from the barracks to the factory), while in the societies of control one is never finished with anything—the corporation, the educational system, the armed services being metastable states coexisting in one and the same modulation. … the man of control is undulatory, in orbit, in a continuous network.34

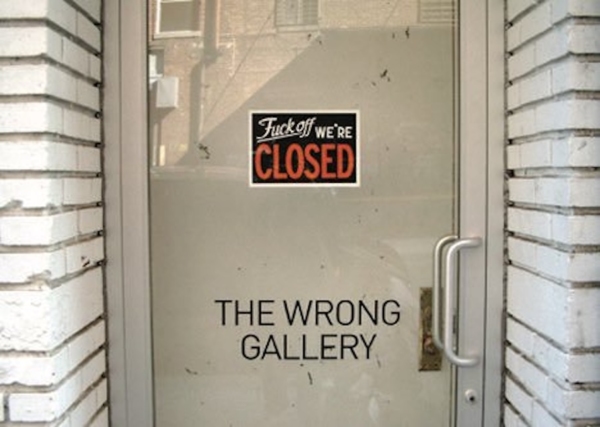

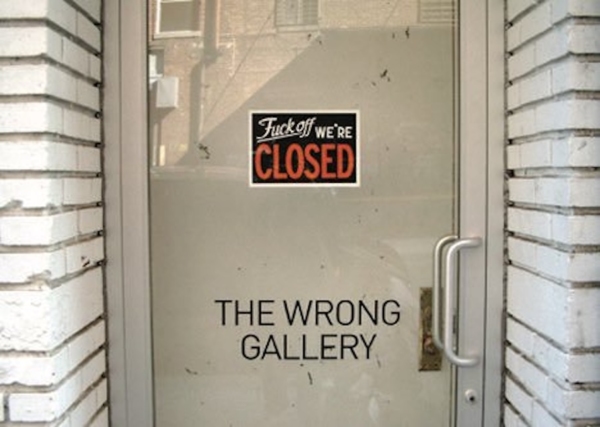

Cattelan’s career has indeed been “undulatory.” Already in this essay I have characterized him as a sculptor, an exhibition planner, a non-profit manager, and an advertising creative. Since the Biennial he has also taken on explicitly managerial roles as a gallery director (Wrong Gallery, 2002–2007) (fig. 4), a magazine editor (Permanent Food [1995–2007]; Charley [2001–]; Toilet Paper [2010–]), and the founder of a direct-to-consumer art business (“Made in Catteland”35 ). The effect of this reinvention (another form of self-production) has been nothing short of a financial windfall. Cattelan’s objects are notoriously expensive—he is one of the priciest living artists, with auction sales of individual objects topping $17 million (Him, 2011, sold for $17.2 million at Christie’s in 2016). And in Cattelan style, he has even taken this fact of his career as an opportunity for jocular self-promotion. In 2019 he became famous outside of the artworld for selling an editioned banana duct taped to the wall of a Miami Basel fair booth for $120,000 (fig. 12). It is difficult to imagine this gesture amounting to something like “critique.”

If we want to find some evidence of resistance in the work—and I am inclined to do so if only because we have spent over 7,000 words describing the art of a millionaire capitalist flourishing in our midst—we won’t find it in the artist’s life and work. We might, however, find it in his death. Because when the artistic critique of industrial capitalism gave way to a more flexible, if also more precarious, form of capitalism, it also, by this same operation, made over every aspect of our lives in the form of this flexible labor and perpetual self-production. Thus, for Cattelan, the fantasy of a true escape from labor ultimately plays out as a parade of death.

His art features an abundance of taxidermy, for example. Dead donkeys, dogs, cats, chickens (Love Lasts Forever, 1995), rabbits (Untitled, 1996), horses (Untitled, 1996), an ostrich (Untitled, 1997) and a bull (Untitled, 1997) have featured prominently. Often, these dead animals operate as surrogates for the artist. In Bidibidobidiboo (1996) Cattelan recreated his childhood kitchen in miniature, placing a taxidermized squirrel at the table next to a pistol, the victim of a self-inflicted gunshot (fig. 13). Dead humans are fair game too. Now (2004) features a life size model of a dead John F. Kennedy lying in his casket (depicted without the gunshot wound). Dead children appear with some regularity, and the child is often another surrogate for the playful Cattelan. In Untitled (2004), small sculptural children were hanged by the neck from an oak tree in Milan. For Daddy, Daddy (2008) another surrogate, the Italian puppet Pinocchio, appears floating face down in the Guggenheim’s fountain—the victim of a fall (suicidal or murderous) from the top of the Museum’s iconic rotunda (fig. 14).

In every case, these oddly peaceful if horrific installations read as the only true escapism in Cattelan’s art. For an artist who has so fully embraced the self-productive entrepreneurialism of contemporary capitalism—an artist whose brand turns on his ability to leverage the creative management of all aspects of life in order to afford an escape from manual labor—the only real escape from work left is an escape from life itself.

And yet… Even in death, Cattelan’s art does not seem particularly catastrophic or critical. His taxidermized animals are morose, but also always a bit funny. Is there a scam in this work too? Something akin to the investment strategy “buy, borrow, die” wherein the wealthy buy equities, borrow money against them to live tax free, and eventually die, passing their estates, also tax free, on to their heirs? Cattelan’s joke here is to maybe work around that paradigm—to die many times over so that he can capitalize on the value produced in his death without actually dying. I’m not sure. Nor am I resolved to the complicit force of his work. At its worst, Cattelan’s art smartly exacerbates the logic of Italian Marxist and punk antagonism into an advertisement for a dangerous new iteration of capitalism. His wealth and creativity, like that of so many other “edgy” or “rebellious” millionaires and billionaires today, models a false promise to precarious laboring workers, enforcing their enthusiastic participation in a New Spirit of capitalism that offers only precarity in return. But remember that Cattelan was born into the Italian working class that Negri addressed, unlike so many of today’s “critical” artists (and critics and art historians) who were born into the comfort of the professional and capitalist classes. This fact alone does not make him a class warrior, but it does give him a rare (for a famous artist) perspective on the options that Marxian theory offered the working class during one of the last significant labor movements of the twentieth century (Workerism): open class conflict à la the violence of Italy’s Years of Lead, or peaceful class transformation in the form of Negri’s service economy. Maybe Cattelan’s provocative art—and his well-known dodginess regarding interviews—only offers a rebuke to the left of his childhood: “I use the words you taught me. If they don’t mean anything any more, teach me others. Or let me be silent.”36

Notes

For his first solo show at Galleria Neon in 1989, the Italian Maurizio Cattelan locked the door and hung a sign that read, “Be back soon” (fig. 1).1 The artist was not back soon, however, and the gallery remained closed for the “show.” Four years later, for an exhibition at Galleria Massimo De Carlo, he repeated the gesture by bricking shut the front door. This time, the only object on display in the space, which was only visible through a gallery window, was a small mechanical toy teddy bear traversing the gallery by tightrope.2 Both of these early exhibitions reveal what would become a persistent quality in Cattelan’s art: his humorous ability to leverage art world and art institutional conventions in order to escape from physically making art.

For these two shows in particular, the art historical convention that Cattelan employed was gallery blockage. In the 1990s and early 2000s, art gallery interruption became a recurring gesture among certain artists producing site-specific, institutionally-reflexive art. For an exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York in 2001, the duo Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset covered the gallery’s door and window with signage that read “Opening Soon: Prada.” The work did not explicitly prevent the public from entering the space, although that was the result (fig. 2).3 Two years later, as part of his 2003 contribution to the Spanish Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, Santiago Sierra sealed the pavilion entrance with cinder blocks, allowing only Spanish passport holders to enter the space via a back door. The number of similar projects in these years, when including artworks that effectively—if not literally—closed their exhibition spaces, is quite large. Mathieu Copeland and Balthazar Lovay attempted to compile a comprehensive list in 2017 with the monumental anthology The Anti-Museum and accompanying exhibition, “A Retrospective of Closed Exhibitions,” at Fri Art in Fribourg, Switzerland.4

In form at least—that is, the form of closure—these projects reintroduced a practice of institutionally-critical Euro-Atlantic art from the 1960s. Daniel Buren’s first solo show, held at Galleria Apollinaire in Milan in 1968, featured the artist’s soon-to-be characteristic horizontal stripes blocking the gallery’s door (fig. 3).5 Robert Barry’s Closed Gallery Piece, a work that “traveled” to three galleries in 1969, consisted only of promotional announcements declaring that the galleries would be closed for the duration of the show.6 One of the galleries involved, Eugenia Butler in Los Angeles, was part of a small network of commercial spaces committed to conceptual work by American and European artists. This network also included Claire S. Copley Gallery (Los Angeles) where, five years later, Michael Asher removed a wall that divided the exhibition space from the back office for a project that simultaneously exhibited the gallery’s business operations while continuously interrupting them.7

Whatever tactical similarities Cattelan’s art shares with his predecessors, however, his redeployment of them was not a matter of institutional critique. For the Cattelan, the fact that gallery closure was both art historical and part of a contemporary zeitgeist made it a useful platform for mounting an escape from physical labor (from actually making art). Nancy Spector, in the exhibition catalogue for Cattelan’s Guggenheim retrospective in 2012, chronicled his gallery closures as part of a pattern of work refusal. “[F]or Cattelan, the gallery is not a space to mystify or demystify, it is merely a place of employment, which he approaches with the same rebellious attitude he would display toward any job” (MC 29). In an interview with the curator, Cattelan traced this talent for absenteeism to his youth in Italy. After he was fired from two different jobs (first at a laundry, then at the Church of Saint Anthony in Padua), he developed a scam:

I worked in a morgue, and I was fed up with it. I found a doctor who was willing to help me. In Italy, we have a system that if you are sick and can’t work, your company has to pay your salary anyway. Not bad. I was paying the doctor, and he was giving me days off. I took about six months off. (MC 32)

In his telling, the deception freed him from work at the morgue. But the tactic was not devoid of work altogether. In addition to bribing the doctor, Cattelan needed to be familiar enough with national-industrial entitlements programs that he could navigate them in his favor. My argument in this essay is that much of Cattelan’s claimed “escapes” from work (escapes that form a central tenant of his artistic practice) are not escapes at all. They are instead substitutions that translate the physical labor of art making into the bureaucratic labor of art making, and they do so via an expert deployment of accepted art institutional conventions (in the examples above, the convention of gallery closure). As his career developed over the 1990s, such bureaucratic labor would become more pointedly managerial in character. In this way, Cattelan’s art reflects and exaggerates a specific shift in both international capitalism and its critique that took place in the 1980s and 1990s—a shift to “creative” management practices as a hallmark of the “New Spirit” of international capitalism.

I borrow the term “New Spirit of Capitalism” from Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello’s book by the same title (1999), a text in which the authors articulate the historical development of capitalism through its integration of the critical positions of previous activist generations. With each new iteration, capitalism also develops a novel “spirit,” which describes both this integration of prior critique and the related set of justifications offered to workers to encourage their enthusiastic support for newly (or at least differently) exploitative working conditions. In the 1960s, the “second spirit of capitalism” was coming to an end. This spirit had long promoted itself to workers by offering “liberation from the specific alienation of the proletariat (its exploitation)” in the form of security. “[J]ob security and income from work were improved in exchange for working-class population settling, and the development of factory discipline.”8 In this way, the second spirit of capitalism integrated Marxist capitalist-critical positions (in regard to alienation) and sold itself to workers in late industrial Euro-America with the promise of increased stability as long as workers were willing to relinquish control over where they lived (i.e., in proximity to manufacturing centers), how they spent their labor time, and even how leisure and work time were divided.

In the 1960s, a new critique emerged from this second spirit—the “artistic critique”—aimed at the oppressiveness of centralized planning and its control over the shape and articulation of worker’s lives. “Demands for autonomy and self-fulfillment assumed the form given them by Parisian artists in the second half of the nineteenth century, who made uncertainty a lifestyle and a value” (NS 434). In the 1990s, the new spirit of capitalism integrated this artistic critique, and abandoned its offer of security and stability (unions, pensions, etc.), replacing it with labor oriented to “projects,” novelty, invention, and endless new beginnings. The authors find evidence for this shift in managerial texts, the kind of pseudo-scientific motivational and corporate structuring advice used by managers and business leaders to shape their organizations. Thus, the new spirit of capitalism was oriented, primarily, to encourage and facilitate the managerial classes, which became the exemplars of post-industrial, Euro-Atlantic capitalist labor.

But the effect of this liberalization for most workers was not liberation. Instead, increased “creativity” in the workplace translated into labor expectations that included constant reinvention and flexibility, insecure employment, endless job changes within and among companies and, eventually, erasure of the distinction between labor and leisure. The ramifications for the global economy have been tectonic: “unskilled jobs [are pushed] into less adventitious statutes, into subcontractors and/or insecure contracts” (NS 236) producing an abundance of precarious gig workers; sex discrimination creates new antagonisms between workers—where once women were excluded from the workforce, “Employers [now] use women’s search for part-time work to generalize underemployment contracts that subsequently become the norm in certain occupations” then “women suffer significant discrimination when it comes to being hired” (NS 240). As labor is destabilized it also becomes more intensive—workers are no longer paid by the day, they are paid by outcome, which means no breaks and no down time. It also means no on-the-job training, which was once the responsibly of companies and firms. Instead, training cost is incurred by individual workers (often in the form of student loan debt) or, in some countries, the state, which is now also responsible for the social costs of labor (healthcare, etc.). To be sure, this new spirit of capitalism has been a boon for some lucky individuals. Wages for top level managers and C-suite executives have never been higher, and their work often looks more like creative play than physical labor (think Elon Musk). But their labor experience is hardly the norm.

This transition from a 1960s artistic critique to 1990s creative labor maps loosely onto the gallery closure projects of the decades I describe above. In the 1960s, gallery closure emerged alongside a critique of the oppressive structure of the commercial art system, which had become a determining force of the creative labor of working artists. Asher recalls:

A critical analysis of the gallery structure was developed by a small number of artists in the late sixties and early seventies. … They believed that artists of previous generations had accepted uncritically … a distribution system (the gallery/market) which had often dictated the content and context of their work.9

The institutionally-critical tactics of this generation of post-minimalist artists had many targets—in Asher’s case, and, a few years later, in the work of Hans Haacke, those targets were primarily the systems of display and exchange codified in museums (note that “closure” in this time was primarily sited in commercial spaces). And in much of this work, artists were already imagining their labor as administrative if not managerial. Research and concept development overtook fabrication and production in these early post-minimalist practices. The transition from industrial to managerial capitalism as articulated by Boltanski and Chiapello was neither instantaneous nor absolute, especially in the realm of artmaking. Nevertheless, as deployed by this generation, the tactic of gallery closure was decidedly critical of the spaces it occupied.

By the 1990s, the shift in post-studio artistic labor from production to management was more profound—not only were artists generally in the habit of hiring assistants, but their project-based work looked more like conceptual labor, brainstorming, installation management, and oversight than like the manual labor of studio work. Thus, in the 1990s, closure work like that of Elmgreen and Dragset lost its critical edge in favor of a more complicit, or at least jocular, relationship with powerful institutions of art display and exchange. When asked about their relationship to the art market, for example, the duo once noted, “It’s like having a demanding and chronically unfaithful lover. Some say ‘Don’t bite the hand that feeds you,’ but biting can be pretty sexy.”10

Lane Relyea, a critic of this shift, describes these 1990s post-studio artists as of a kind with the “post-Fordist free agent and entrepreneur,”11 figures whose life and work have been entirely reconfigured by the promises of the New Spirit of Capitalism. However, in his analysis, artistic labor from the 1960s through the 2000s was threaded not only through the labor conventions of productive work, but also through the punk ethos of DIY culture, which emphasized self-reliance and individual management of all facets of production. (For example, a DIY magazine producer might be responsible for content, layout, design, printing, and distribution.) This ethos somewhat counterintuitively prefigured the transition from artistic-labor-as-object-production to artistic-labor-as-social-production. As it turns out, Cattelan’s artistic practice can be read through punk and hardcore DIY youth culture, too (more on this soon), although in the case of his early gallery closure projects, the transition from 1960s critique to 1990s capitalist spirit first appears quite simply and directly. In these projects, a closed exhibition space no longer evidences an artistic critique of the oppressive structures of the commercial gallery system. Rather, it amounts to a creative (or at least clever) displacement of physical art “work” by administrative labor (that is, in the examples of his closed exhibitions, Cattelan did not make any physical objects, but he did make administrative decisions with regard to signage and the deployment of historical and contemporary artistic idioms).

In these early projects, Cattelan’s artwork was certainly administrative, but it was not yet “creative management.” That changed in 1993, at the Venice Biennale, when the artist first successfully integrated his refusalist pragmatics with creative managerial labor (fig. 5). That year, Cattelan’s invitation to participate came with a central space for installation. The artist, in turn, leased the space to an advertising agency, which hung a billboard for a perfume (MC 195). As before, Cattelan was able to leverage conventions of art institutional practice (specifically the processes by which artists design and execute installation work for the central space at the Biennale) to escape from the work of physical artmaking. Here again, there are resonances between Cattelan’s single perfume billboard and the all-but-empty spaces of the “closed” galleries of his cohort of 1990s artists (recall that Elmgreen and Dragset’s closed gallery featured only a “coming soon” Prada sign). But now Cattelan also substituted the labor of middle-manager for the labor of creative producer. He effectively managed his Biennale space in order to turn a profit.

Through the lens of exhibition space closure alone, Cattelan’s escapist gestures read as little more than self-serving quotations of artistic practice. But if we trace Cattelan’s jokes to their roots in the soil of his Italian childhood, they offer evidence of how leftist sentiment is recruited into the spirit of capitalism. Indeed, the most provocative and most frustrating aspect of Cattelan’s art is how it models the integration of left-wing, intellectual, and worker anti-capitalist activism into the spirit of creative managerial capitalism broadly. His adept manipulations of art historical practice (which, to be sure, evidence a sophisticated understanding of not only the critical stakes of, in this case, early post-minimalist art, but also the legacy of administrative labor that contemporary art practice inherits) operate in allegorical relationship to capitalist-critical Italian intellectual history and its integration into labor conditions under Euro-Atlantic capitalism in the 1990s.

Cattelan titled his Biennale perfume project Working is a Bad Job, which is humorous, certainly, but also effects a subtle reformulation of Antonio Negri’s 1973 Potere Operaio pamphlet “Workers’ Party Against Work,” a Marxist-Leninist reading of the working class, value, and exploitation.12 The Marxist movements of 1960s and 70s Italy (Operaismo, Potere Operaio, and its later worker autonomy iteration, Autonomia Operaia) filter into Cattelan’s art in this way—humorously and subtly.13 Some of his earliest projects, including Christmas ’95 (1995) and Untitled (1996) détourne the iconic star symbol of the Red Brigades, a terrorist group affiliated with Workerist causes (fig. 7).14 In these artworks, Cattelan’s addition of a tail transforms the radical star symbol into a festive shooting star logo, which he then used as part of a Christmas nativity scene and an exhibition invitation card, respectively. In the case of Working is a Bad Job, Cattelan simply adapted Negri’s counterintuitive title and injected it with a blend of cynicism and cleverness. In the essay, Negri describes the evolution of the working class to a “level of productivity and ‘refinement of their talents’” that allows workers to “imagine their life not as work but as the absence of it, their activity as free and creative exercise” (BB 75). At the same time, he argues, the modern mass industrial worker has begun to unify and constitute itself “as a power that blows up the conditions of the production of surplus-value and that by means of the rule of value takes every mystified rationale away from capital’s domination.” The result, according to Negri, was an Italian working class increasingly able to refuse work in favor of appropriating its own surplus labor (BB 76–77).

What might this new working class look like, according to Negri? From the vantage of the 2020s, his conclusions are startling: “We are talking about the massive flight of productive labor from factory work toward the tertiary or service sectors” (BB 75). It is difficult today to imagine our precarious service sector, which includes low-paid fast food workers as well as middle-class managers, as liberated. But for Negri, this transition is a spontaneous move—an empowering move—precipitated by the working class that constitutes the possible origins of a new class consciousness. Negri’s analysis of postwar industrial capitalism is decidedly Marxist in orientation. Nevertheless, read through Boltanski and Chiapello’s account of capitalist evolution, Negri can be situated well within a broader, post-Marxist critique—what Boltanski and Chiapello call the “artistic critic”—of capitalism. Plainly, Negri’s polarizing of “work” and “free and creative exercise” suggests that, at least within the logic of this pamphlet, older movements for security and stability in work have been displaced by a new desire for freedom and creative expression from work. That freedom, according to Negri and, in turn, Cattelan, look like white collar and service work rather than productive factory (or studio) work.

Here is the lesson that Cattelan’s art has adapted from his Italian Workerist countrymen: by shifting the emphasis of his artistic work from studio labor to managerial labor he is able to claim an escape from “work.” To be sure, Cattelan’s art still requires labor, but under this paradigm it now requires the kind of creative administrative labor that was used in the 1990s to sell a new iteration of international capitalism to increasingly precarious workers. Like Negri’s mass worker, the contemporary artist has reached a level of productivity or “refinement of talent” that allows him to imagine art production not as physical labor but as “free and creative exercise.” However, he replaces Negri’s vision of a united working class freeing itself collectively from exploitive labor with a creative administrator promoting only himself for the sake of work refusal. The result is that Cattelan in fact generates an abundance of new kinds of flexible, creative work with each project, and not only for himself but for the many people (curators and other museum workers especially) that must deal with him. He effects this transition by leveraging what we might call the artist’s surplus labor—that is, the creative work in excess of the production of objects that transforms them into art. For Cattelan, this excess labor involves the appropriation of the conventions of art display. In the case of Working is a Bad Job, he simply repurposed the space of the Biennale in order to turn a perfume ad into an artwork (and, by extension, into an escape from the physical labor of object production).

However simple that gesture was in practice, the sited Working is a Bad Job had rather complex allegorical force. It was installed as part of the Venice Biennale, an international showcase that was originally conceived, in 1895, as a national showcase. Thus, the platform was already an appropriate venue for Cattelan to mark the integration of Italy-specific concerns into a Euro-Atlantic discourse. But not only was the work part of the Venice Biennale, it was installed as part of Aperto ’93, a rhizomatic group show unaffiliated with any single nation (that is, distinct from the national showcases of the Venice Pavilions). Aperto ’93 (Open ’93) took place in the Corderie building of the Arsenale, and thus relatively far from the national Pavilions. The show was conceived as a reformulation of Aperto (1980), a sideshow of young artists that was inaugurated by Achille Bonito Oliva and Harald Szeemann. In 1993, Bonito Oliva was now the artistic director of the entire Venice Biennale, and in his reformulation, the new Aperto was to showcase young curators rather than young artists (evidence of a shift from productive to administrative creative labor within the logic of the Biennale as a whole).

The 45th Venice Biennale marked a significant moment in the history of the festival, which was under pressure from an Italy in decline and waning interest in the “national art” model of the event. Clarissa Ricci has described the pressures on, and significance of, the 1993 festival in detail in “Towards a Contemporary Venice Biennale:”

The devaluation of the Lira in 1992 caused the temporary withdrawal of Italy from the European Monetary System (EMS). The consequences of increased taxation, together with policies to curb public spending, was accompanied by corruption scandals known as “Tangentopoli” (Bribesville), and together this caused the First Italian Republic to collapse. While this epochal shift was occurring, the Biennale was losing its international impact. Its national pavilions were viewed by some as anachronistic and visitor numbers had dropped.15

Bonito Oliva was tasked with transforming the Biennale into a truly global art event, and he did so through recourse to an “open,” distributed structure, geographically-diverse content (Chinese artists were included in the 1993 show for the first time), and a turn to an expanding field of creative practice. Within the logic of the Biennale, that meant a total of fifteen different curated exhibitions, including Aperto ’93, which featured its own thirteen interconnected curatorial projects on the theme of the “emerging” global economic/cultural paradigm, educational programming (including a school for curators in partnership with École du Magasin), and an overwhelming (to many viewers) abundance of projects and ancillary events. As Ricci describes them, “[A] conference [on the “Production, Circulation, and Conservation of Artworks”] and the school for curators were part of a larger educational project that was meant to be the backbone of the Biennale’s permanent activities. [This larger educational project], which was only partially realised, also comprised events and shows throughout the exhibition’s duration.”16

These events—which cost much more than the Biennale’s budget—were paid for by Bonito Oliva’s aggressive fundraising campaign and were thus “powered by the intellectual and managerial energies of Venetian entrepreneurs.” In short, the faltering Venice Biennale model was, in 1993, given new life by an artistic director whose plan celebrated curatorial work and the far-reaching administrative labor of conference and event planning. It was, in a word, the first truly “neoliberal” Venice Biennale.17 And it was there, in Cattelan’s home country of Italy, in the Arsenale, as part of an “open” curatorial showcase, funded, as it was, by Italian entrepreneurs, that Cattelan refused work by renting out his gallery space in order to make some additional money.

Born in 1960, Cattelan would have been too young to participate in Northern Italy’s early Workerist movements, even if his home city was a locus for some of its main branches.18 Negri, who was also born in Padua and taught at the University of Padua beginning in the late 1950s, was one of the founders of Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power), an affiliation of labor groups and activists committed to a Marxist reading of Italian industrialization. Cattelan came of age a decade later in the midst of the region’s “Years of Lead,” a time of violent confrontations among the radical left, the fascist right, and the police, which resulted in widespread fear of both terrorism and incarceration. Padua was a central city in these years, the site of the first murders committed by the Red Brigades. Around this time, in the mid-1970s, cynicism and irony began to creep into Workerist projects as younger workers and students joined the cause. Bologna’s student movement in 1977, for example, which remained worker-centric but came to include university students, small shop workers, feminists, precarious workers, and social misfits, often made use of humorous or defeatist slogans. (For example, “Gui e Tanassi sono intelligenti, siamo noi i veri deficenti” [“Gui and Tanassi are smart, we are the real morons”], which refers to Italian politicians who were accused of taking bribes from Lockheed Martin in the mid 1970s.)19

A much more aggressive cynicism arrived in Italy with the hardcore punk youth culture of the following decade. Bands like Raw Power (whose name bears a passing resemblance to Potere Operaio), The Wretched, I Refuse It! and RAF20 adopted the bombastic language of Italian worker activism and blended it with the angry, though also often ironic, nihilism of punk’s “No Future” ideology.21 Autonomia Operaia had a significant influence on the attitudes and style of address of these Italian punks, especially in the early years. In an interview for the 2015 documentary Italian Punk Hardcore 1980–1989: The Movie, Stefano Bettini, singer for I Refuse It! describes the scene’s origins:

During the early years, back in like ’77, … I was 15–18 years old, but I believed that it was normal for people my age to participate in the autonomy movement. Then, all those things from England came out: the Sex Pistols were the first.22

Like punk movements elsewhere, influences in Italy arrived piecemeal from English-speaking countries—first the U.K., then the U.S. This wave of anarcho-cynicism merged with the falling tide of Italian Workerism.

For bands like Peggio Punx, who initially had more interest in social and political antagonism than music making, humor became a key part of a project of cynical social refusal. According to its members, the band started as a practical joke:

We had the idea of pulling a hoax in the same way as the Sex Pistols’ “Great Rock n’ Roll Swindle.” We wanted to create a lot of hype for a band by filling the city with graffiti and fliers, and so we did. We wanted to set up a fake gig, collect the money, and then flee.23

These were Cattelan’s compatriots—working class, angry, and alienated—and their cynicism was of a kind with his. Cattelan’s career would be bolstered by a project similar to Peggio Punx’s hoax. For his 1992 Oblomov Foundation he petitioned 100 people for $100 donations to a scholarship—$10,000 in total—that would allow the winning artist to abstain from showing work for one year (fig. 8). According to Cattelan, in the end, no artist would accept the award for fear of damaging his or her career, and so he used the money to move to New York City.24 For both Peggio Punx and Cattelan, the scam turned on their ability to leverage the conventions of their art and its funding and promotion. For Peggio Punx, these conventions included promotional vandalism, Xerox fliers, and ticket sales. Cattelan’s scam leveraged the conventions of international art awards, foundations, and the tradition of charitable giving.

Here is the revelation of Cattelan’s work, because whatever origins his practice had in working-class Italian sentiment, his professional career has been characterized exclusively by creative administrative practices. This shift is most evident at the level of absenteeism. Where many of Cattelan’s artistic punchlines suggest that the artist has weaseled out of “work” (i.e., Working is a Bad Job), in fact, the artist has merely substituted the labor of creative administration for the labor of production. In the case of the Oblomov Foundation, Cattelan’s claim that the funds were designed to facilitate a break from work is undermined by the fact that the money was generated by his own sustained managerial labor (mostly raising capital via networking). Because Cattelan’s work is in direct conversation with the Workerist roots of his native Padua—a conversation he invokes not only through his interest in absenteeism but also by his overt use of the Red Brigades’ symbol—his turn is not just humorous (as so many critics suggest), it is aggressively cynical. More cynical, indeed, than the hardcore punks who preceded him, because while their angry refusal offered a DIY and often rather selfish rereading of Workerist refusal, their projects were still largely hostile to the functioning of international capitalism and, individually, most of the bands were resistant to anything like “selling out.” Cattelan’s work, on the contrary, is all about selling. His art exploits the fact that the Marxist artistic critique of industrial labor fomented in his hometown has been fully integrated into postindustrial managerial capitalism. Cattelan is thus the new “creative” Company Man, an artist who has embraced the promotional message used to sell this new spirit of capitalism: that freedom from work comes in the form of flexible, entrepreneurial management (which, in this new formulation, is not “work”).

Cattelan took this message with him to America (funded, as he was, by the Oblomov scam), where he honed his administrative “escape” from work. In 1995, a few years after his arrival, he and curator Jade Dellinger hatched a plan to use university funds to pay for a touristic vacation to Florida. Dellinger had been developing his own parasitic exhibition program within the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) for years. Under the series title Use as Directed, these smaller interventions were slipped into CAM’s regular programing every several months without the need for space or support (aside from a nominal stipend of $1,000 from the university). Dellinger invited Cattelan to pitch a project for the series, which eventually became Choose Your Destination: How to Get a Museum-Paid Vacation. The conceit was simple: Cattelan and Dellinger used the $1,000 stipend to pay for Cattelan’s flight to Florida and for tickets to the state’s amusement parks. The collaborators stayed (for free) at the home of Dellinger’s parents and used their car for transportation. They then documented their travels with souvenir snapshots at parks and beaches, including Busch Gardens and Disney World, and with a small series of novelty caricatures.25

In Cattelan’s titular formulation, the project was something of a scam—a manipulation in which the artist demonstrates how to trick a museum into paying for a vacation. But in practice the “vacation” was exhausting. Their days were filled with touristic events designed to produce a body of documentary images, they made a limited-edition invitation card (out of a détourned found Florida postcard), and in the end the artist and curator gave a public lecture at the museum. As Cattelan admitted in early faxed correspondence to Dellinger, “we are to work hard and the lecture has to be SUPER PROFESSIONAL” (fig. 9).26 The fact that the artists corresponded via fax machine evidences the project’s white-collar sympathies, as does the claim to professionalism. And the reference to hard work underscores the fact that the vacation was not much of an escape from labor but rather a labor translation.