“The particles of language must be clear as sand.” —William Carlos Williams1

“Language is as primary as steel.” —Robert Smithson2

“The knot is neither hemp nor cotton nor nylon: is not the rope. The knot is a patterned integrity. The rope renders it visible.” —Hugh Kenner3

I

In the late 1940s, William Carlos Williams’s understanding of modern art suddenly became inseparable from an origin story about it. Regularly featuring the anecdote in his lectures of the period, he would just as regularly mention how fond he was of telling it. “I have told this story often before,” he says in a 1952 speech published as “The American Spirit in Art,” “but it bears repeating”:

Alanson Hartpence, who used to be with the Daniel Gallery, once, during his boss’s absence, had one of the gallery’s best patrons there looking at a picture. The estimable lady admired one of the paintings and seemed about to buy it—or at least she was leaning that way.

But Mr. Hartpence, she said, what is all this down here in this left-hand lower corner? […]

That, said Hartpence, leaning closer to inspect the place, that, Madame, he said, straightening and looking at her, that is paint.

He lost the sale.

But that is the exact place where for us the virus first bit in. That is the exact place where for us modern art began.4

The story construes the birth of “modern art” as first and foremost the end of representation—what the customer is trying and failing to get an answer about—and the beginning of something else: “paint.” As Williams writes in his Autobiography, just after telling a version of the story, “it is NOT to hold the mirror up to nature that the artist performs his work. It is to make … something not at all a copy of nature, but something quite different, a new thing.”5 That “new thing,” the story says, is painting’s presentation of paint as such, disburdened of its representational responsibilities and finally able to be seen by and for itself. And this presentation, in turn, marks the beginning of a new aesthetic regime, one into which the customer, with her attachment to what Williams calls art’s “medieval and classic criteria,” cannot enter (RI, 218). If, as Henry Sayre puts it, “Hartpence’s modernism” consists in his “willingness to give up the necessity of representation … to forego the objective image and to interest himself instead in paint itself as medium,” his customer’s pre-modernism is her refusal to do the same—hence Hartpence “los[es] the sale.”6

And yet the displacement of the representational by the material that characterizes “modern art” does not, on Williams’s account, mean that art is now “‘about’ nothing other than itself,” as Terrence Diggory has put it.7 To the contrary, as Williams tells us a moment later in “The American Spirit,” the modern artist doesn’t “paint a picture or write a poem about anything” (RI, 218). When the painting no longer represents—is no longer of something—it is also no longer “about” something; “meaning” and “subject matter”—Williams’s terms—are revealed to be vestiges of representation and eliminated along with it. Thus, when he tells the Hartpence story in a 1947 speech, he does so as a corrective to “the tendency everywhere … to overload the verse with ‘meaning’”;8 similarly, in “The American Spirit,” he concludes that, after Hartpence, “You do not select subjects anymore; to classify poems or pictures by their subject matter is today a little childish” (RI, 218). So, it’s not that paint in “modern art” takes itself as its “subject”—that paint “means” paint or is “about” paint. Instead, as Diggory puts it, a “crucial tenet of William’s aesthetic” is that “paint is paint” (EP, 4).9

The stakes of this opposition, not just between materiality and representation but also between materiality and “subject matter,” “meaning,” or what the artwork is “about,” will become clearer as we go on. But it is significant that if the Hartpence story depicts that opposition as a confrontation between two historically specific perspectives—between the pre-modernism of the customer’s commitment to representation and the modernism of Hartpence’s commitment to materiality—a related confrontation can be seen in the history of Williams’s interest in the story itself. As Diggory points out, while the story is set in the 1910s (Hartpence told it to Williams in 1918, according to William Marling10), Williams appears to only have begun telling it in the late 1940s—by which time the world of advanced art had evolved considerably. Diggory suggests that the most relevant change for Williams over that period was the post-war emergence of an ethical discourse around art. “In the years following World War II,” he writes, “the question of aesthetic autonomy, or self-referentiality … was reposed in ethical terms that have continued to fuel critical debate since that time” (EP, 4). Thus, on Diggory’s account, while the Hartpence story had only produced an aesthetic position when it took place in 1918, by the 1940s it could be understood as embodying an ethical one: when paint is allowed to simply be paint, Diggory says, the medium is “preserv[ed],” an ethically salutary act (EP, 5). When paint is wielded in service of representation, by contrast, used “to refer to something other than itself,” “violence” is perpetrated against it (EP, 6). The way to aesthetically resist violence then is to maintain “respect for material,” an ethos that the Hartpence story, according to Diggory, signally announces (EP, 4).

Yet there are also purely aesthetic reasons why Williams may have suddenly taken such a keen interest in the story twenty-five years after its occurrence. To begin with, the transformation it illustrates—the displacement of representation by materiality in the work of art—was far from complete in 1918. To the contrary, as Williams states, it was only just beginning (the story is where “modern art began”), which is why it’s still completely reasonable for the customer in 1918 to want to see the painting as a representation of something—indeed, most of the painting is a representation of something. The conceptual force of Hartpence’s declaration derives precisely from its abrupt—and, to the customer, unreasonable—rejection of the prevailing paradigm.

By the late 1940s, however, when Williams begins telling the story, the displacement of the representational by the material was beginning to reach what would have looked to him like its logical endpoint—a development that Williams seems at various moments to have emphatically disapproved of. At the vanguard of this development was Jackson Pollock, a figure who would, as we’ll see, eventually become significant for Williams’s poetry. As late as 1945 Pollock’s work was, like the Daniel Gallery painting, still capable of powerfully soliciting Hartpence’s customer’s question. Untitled, for instance, is replete with abstract elements, making its object of representation hard to decipher (fig. 1). And yet an object of representation is nonetheless suggested and in fact (according to the Museum of Modern Art, which owns the drawing) can be read: Untitled, they say, depicts “[t]wo totemic figures fac[ing] each other, the right one with its leg bent along the bottom of the sheet.”11 The drawing can thus still be said to be “of” something even as it pushes depiction to the breaking point, and the tension the Hartpence story evokes thus remains in play. The customer (or a viewer at MoMA) would be getting at that tension by asking “what is all this?” (because it’s hard to tell); Hartpence (or an art critic) would be deepening that tension by answering, “that is paint.”

But by 1947—the same year that Williams first told the Hartpence story in print—Pollock had begun making his drip paintings, works in which the last suggestion of representation had been abolished. Of these paintings, such as Full Fathom Five from that year, the customer’s question could no longer reasonably be asked, because “that is paint”—thirty years earlier a radical alternative to the expected answer—had suddenly and conspicuously become the only answer (fig. 2). Whereas the lines of paint in Untitled tend to depict shapes and figures, however abstract, in Full Fathom Five they are ostensibly untethered from any depictive function at all. Thus, the tension between representation and materiality—the possibility, still present in Untitled, that paint could be something other than paint, without which Hartpence’s declaration would have been merely tautological—had by 1947 given way to a materiality that was both conceptually and literally total. Or, put differently: what in 1918 (or even 1945) had been confined to the “lower left-hand corner” of the painting had by 1947 expanded to fill the whole thing.

One way to describe this would be to say that modernism—understood in the terms of the story as the replacement of the representational by the material—had triumphed. Hartpence’s answer to the customer’s question had been art historically vindicated and thereby finalized. But from another perspective, we can see that the finality of that answer had in fact neutralized the tension that produced the question in the first place: when it would no longer occur to anyone to ask, “what is all this?”, “that is paint” loses its force as a radical aesthetic position. And from this perspective, what briefly appeared to be modernism’s triumph begins to look to Williams more like its dead end. It is this version of events that helps us begin to make sense of another of Williams’s texts from the period, an essay on the painter Emanuel Romano he wrote in 1951 while preparing the “American Spirit” speech—a simultaneity that is startling when one comes across passages like the following:

Modern painters … have been afraid of the horrible word “representational”; they have run screaming into the abstract, forgetting that all painting is representational, even the most abstract, the most subjective, the most distorted. The only question that can present itself is: What do you choose to represent?12

This is a far cry, of course, from Williams’s assertion in “The American Spirit” that “you don’t paint a picture or write a poem about anything.” And indeed, his championing of the “representational” here would seem to refute the most basic premise of the Hartpence story itself. “What do you choose to represent?” is, as we’ve seen, precisely what the customer is asking; if that question is, on Williams’s own account, “The only question that can present itself,” she would seem to be more the anecdote’s hero than its villain, with Hartpence in turn playing the role of the hysterical modern running “screaming into the abstract”—obviously a complete reversal of Williams’s basic position as we’ve so far understood it.

This contradiction is further sharpened in Williams’s opposing accounts of Cézanne, one of the most important figures for the poet throughout his career and one who often appeared in close proximity to recitations of the Hartpence story. In his Autobiography, just after telling the story, Williams says that “Cézanne is the first consciously to have taken that step” (A, 240); in “The American Spirit,” similarly, the story reveals “the essence of Cézanne” (RI, 218). Toward the Autobiography’s end, Williams recalls a speech in which he had described “the years when the painters following Cézanne began to talk of sheer paint: a picture a matter of pigments upon a piece of cloth stretched on a frame.” (In the next line he says, right on cue, “I told them the Hartpence story” [A, 380].) Yet in the Romano essay, just after the above-cited critique of the “modern painters,” Williams counts Cézanne among the masters of representation—he was, Williams says, “a great realist” (RI, 197).

Moments like these lead Sayre to rightly note that “Even as [Williams] championed abstraction in the poem and in the painting, he steadfastly believed in the necessity of objective representation” (TI, 129).13 But this contradiction is also far from idiosyncratic to Williams. I want to suggest, rather, that it can be better understood as belonging to the logic of modernism itself—a logic that Williams, perhaps more than any of his contemporaries, nonetheless embodied in his conflictual back and forth on these questions. On the one hand, the eruption of materiality into the representational artwork so vividly illustrated by the Hartpence story will put modernism into motion—it will be “the exact place … modern art began.” On the other, the totalization of this materiality will threaten, as we’re beginning to see, to spell modernism’s end. This essay’s third section will show how Williams forges his poetics within the immensely pressurized conceptual space between these two moments—an achievement Hugh Kenner’s writing on Williams uniquely enables us to grasp. But first, we begin at the end.

II

“There is an objectivity to the obdurate identity of a material,” writes Donald Judd in “Specific Objects” (1965), thus formulating one of the central tenets of the artistic movement that would be known as minimalism.14 Judd in that essay enumerates the common features of “the new three-dimensional work” (DJ, 135), a form he distinguishes from sculpture in part on the basis of sculpture’s subordination of material “identity” to other ends. These ends, for Judd, are primarily the anachronisms of “imagery” and “salient resemblances to other visible things” (DJ, 138): in “earlier work,” for instance, “imagery” leaves the “material” in which it’s “executed” “neutral and homogeneous” (DJ, 143); in work that “imitat[es] movement,” similarly, “the material never has its own movement” (DJ, 138). In the “new work,” by contrast, materials are permitted to be “specific.” And that means, in a tautology characteristic of Judd, that “Materials … are simply materials” (DJ, 143).

The tautology is also, of course, reminiscent of Hartpence—both in its structure (materials are materials, just as paint was paint) and in terms of what it rejects: representation, the “mirror up to nature” form of art that Williams, in his Hartpencian mode, casts aside. And although Judd takes additional pains in “Specific Objects” to argue the new work’s differences from (and superiority to) painting, those differences are nuanced by his famous qualification that “The new work obviously resembles sculpture more than it does painting, but it is nearer to painting” (DJ, 138). This nearness would consist, for Judd, in painting’s having pushed materiality as far as it could go in the “rectangular plane” before exhausting that form (“A form can be used only in so many ways,” he writes [DJ, 136]); the “new work,” in a sense, would simply continue painting’s materialist trajectory out into three dimensions, thereby doing what sculpture had failed to do. In that respect, Judd counted one painter as an especially crucial precedent, one to whom he returns in his writings again and again: Pollock. “I think Pollock’s a greater artist than anyone working at the time or since,” Judd writes in a 1967 essay, explaining that that greatness is in large part due to the painter’s “use” of “paint as material.”15 “This use,” Judd says, is “one of the most important aspects of Pollock’s work,” and it is grounded in Pollock’s allowing his paint to retain all of its material specificity as it’s applied to the canvas (DJ, 191). “The dripped paint in most of Pollock’s paintings is dripped paint,” Judd writes in another characteristic, and even more Hartpencian, tautology. “It’s not something else that alludes to dripped paint” (DJ, 191–92).

Paint does, however, exhaust its usefulness. And the impersonal, industrial materials often used by the artists associated with minimalism—“formica, aluminum, cold-rolled steel, plexiglas, red and common brass, and so forth,” as Judd lists in “Specific Objects”—seemed to Judd particularly suitable for an art that would push the materialist tautology originated by Pollock to the next level (DJ, 143). Yet the same materialist aesthetic that attracted minimalist artists to the “obdurate” qualities of aluminum and brass would draw others, such as Judd’s younger colleague Robert Smithson, also in the exact opposite direction—not just to the relative straightforwardness of materials that seemed to naturally resist the tendency toward “allu[sion],” but also, more paradoxically, to the most allusive medium of all, and the one with which Williams was most preoccupied: language.

Thus, in 1967 (the same year that Judd published his essay on Pollock), Smithson co-organized a show for the Dwan Gallery on the theme of language, titled “Language to be Looked at and/or Things to be Read.” In the short but complex press release for the show, Smithson begins some preliminary theorizing toward the notion of a radically materialized language.16 Distinguishing between “literal” and “metaphorical signification,” Smithson attributes a quasi-magical power to the former when the latter is done away with: “Literal usage becomes incantatory when all metaphors are suppressed” (LL, 61). Yet eliminating metaphor, he determines, is not enough, since metaphoricity is revealed to infect literal speech all the way down. “[D]iscursive literalness is apt to be a container for radical metaphor,” Smithson writes. “Literal statements often conceal violent analogies” (LL, 61). It will thus take actual material literality, not merely linguistic literality, to get a truly materialist version of language: in the ideal scenario, “language is … not written” at all, but “built” (LL, 61). Smithson gestures further toward this deeper materialism by signing his name “Eton Corrasable”—a reference to Eaton’s Corrasable Bond, a then-popular erasable typewriter paper. Yet, apparently feeling the need to make the point more strongly (and clearly) five years later, Smithson would append a one-line postscript to the text in 1972. It reads simply, “My sense of language is that it is matter and not ideas—i.e., ‘printed matter’” (LL, 61).

We can see Smithson developing toward this highly refined version of the position in the intervening years between show announcement and postscript. “[L]anguage and material … are both physical entities,” he says in a 1969–70 interview. “I’m concerned with the physical properties of both language and material, and I don’t think that they are discrete” (RS, 208). For “language” and “materials” not to be “discrete,” for both to have as their only relevant characteristics their “physical properties,” is, for Smithson, to conceive of language in much the same way that Hartpence conceived of paint: not as something representational, something standing in for something else, but as something—in Smithson’s word—“primary” (RS, 214). And for language to be “primary,” just another kind of “material,” is for it to not belong to the realm of the “ideal”: “I don’t think that language … is an ideal thing,” he says in the same interview, “but that it’s a material thing” (RS, 213).

Teasing out the implications of a language construed as material but not ideal, Craig Dworkin puts Smithson’s 1972 “matter and not ideas” addendum next to Mallarmé’s famous quip about poetry to his friend Degas:

Smithson’s formulation, tellingly, recalls Stéphane Mallarmé’s sense of poetry itself. Responding to Edgar Degas’s complaint that it was easy to come up with good ideas for poems but hard to arrange particular words, Mallarmé wrote back to his friend: “Ce n’est point avec des idées, mon cher Degas, que l’on fait des vers. C’est avec des mots [My Dear Degas, poems are made of words, not ideas].”17

On the face of it, the parallel makes sense: in comparing Smithson and Mallarmé, Dworkin renders the former’s “matter” as analogous to the latter’s “words,” the two terms united in their opposition to “ideas.” Yet if Mallarmé produces a distinction between “words” and “ideas,” it is not to purge language of any “ideal” dimension whatsoever; the words, even in a Mallarmé poem, still signify. For Smithson, on the other hand, they don’t. If, as Smithson says, “a rock would be compared to a word,” making them “interchangeable” because “they are both material,” we have gone quite a distance from the kind of “words” Mallarmé is talking about (RS, 209). Indeed, the whole force of Smithson’s identifying language with “matter” is, in a sense, not to link “matter” with “words” but precisely to open a conceptual gulf between them and thus to work exactly against what Mallarmé says to Degas: for Smithson, “words” are not opposed to “ideas” because what Mallarmé (and everyone else) means by “words” are indelibly permeated by “ideas.” For a word to be a “physical entity,” by contrast, is for it to functionally cease being a word: as Smithson says in the “Language to be Looked at” text, “the ‘object,’ takes the place of the ‘word’” (LL, 61).

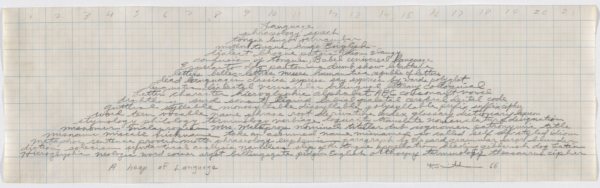

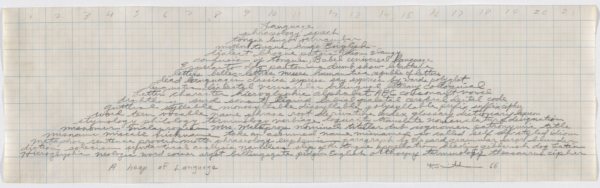

Put more simply, Smithson and Mallarmé can’t possibly agree with one another because a poem written with “words” as Smithson conceives of them—words that are “built” on the page and “not written”—would no longer be a poem. Instead, it would be something more like a drawing. And indeed, as Dworkin himself argues in a separate essay, Smithson makes just this point in his 1966 drawing A Heap of Language (fig. 3). The work literalizes the title: cramped words in Smithson’s cursive hand—words that Dworkin informs us are culled from the entry for “language” in Roget’s Thesaurus—are piled into a loose pyramidal form on numbered graph paper.18 But in comparing Smithson’s writing to the source material, Dworkin observes that the transcription is spotty, full of omissions and substitutions. There is, he says, a logic to be discovered in Smithson’s transcription process, but it is a logic that issues from the physical shape of the heap rather than from anything having to do with the meanings of the words themselves. “In all cases,” Dworkin explains, “the deviations [from the original text] were made to maintain the even incline of the heap. Sloping at about forty degrees, the text’s margin mimics the angle of repose of moderately damp soil, sandy gravel, or crushed asphalt”19—the kinds of materials Smithson often used in his three-dimensional work. In this way, then, A Heap of Language shows us what a totally materialized language actually looks like: in place of the meaningful relations between words that would involve them in “ideas” (and thus make them language “to be read”), there are only the “material” relations that pile them into a heap—a “language to be looked at.”20

What A Heap of Language adds to Smithson’s statements about language is thus to show how treating language as “a material thing” rather than “an ideal thing” involves rethinking not just words themselves but also the way they are organized and beginning to conceive of them, in the terminology Smithson adopts from linguistics, as devoid of “semantics”—language’s meaningful dimension—yet still ordered by a “syntax”—language’s non-meaningful structuring principles. While the words appear to have neither a semantic nor syntactic relation to one another, their purely material relations (the imagined gravity that holds them together in a heap) are part and parcel of how Smithson understands the syntactic. Writing of Carl Andre’s prose style in 1968—in a paragraph that itself serves as a capsule summary of Smithson’s theory of language—Smithson says that “Semantics are driven out of his language in order to avoid meaning,” with “meaning” here associated with the “ideal” realms of “thoughts” and “reason” (“Thoughts are crushed into a rubble of syncopated syllables,” he writes of Andre’s prose. “Reason becomes a powder of vowels and consonants”).21 Judd’s writing, meanwhile, is equally material for Smithson (it is a “brooding depth of gleaming surfaces”) and thus equally devoid of semantics, yet that very material meaninglessness—characterized by Smithson, in a favorite word, as an “abyss”—is brought under the heading of syntax: “Judd’s syntax is abyssal—it is a language that ebbs from the mind into an ocean of words” (MOL, 80).

If semantics is identical with meaning, then, Smithson defines syntax precisely by its non-identity with meaning—a point he repeats again and again. Whereas he characterizes semantics as the verbal manifestation of “thought” and “reason” (and thus as something for Andre to “drive[] out”), “each syntax” in an artist’s writing “is a … set of linguistic surfaces that surround the artist’s unknown motives” (MOL, 82), the meaningfulness of “motives” entirely delinked from—more, obscured by—the material quality of syntactic “surfaces.” In his well-known essay, “A Sedimentation of the Mind,” also from 1968, Smithson associates “words” with “rocks” on the grounds that both “contain a language that follows a syntax of splits and ruptures”—a syntax similar, perhaps, to that which breaks up a thesaurus entry in order to pour it into a heap.22 Once again, syntax not only has no relation to meaning, but it also comprises the active impediments to meaning of “splits” and “ruptures” and, a moment later, “fissures”: “The names of minerals and the minerals themselves do not differ from each other, because at the bottom of both the material and the print is the beginning of an abysmal number of fissures.”23 Unlike semantics, syntax is no threat to the meaninglessness of materiality. For Smithson, syntax is simply materials’ “abysmal” structure.

For all of Smithson’s insistence on the non-meaningfulness of syntax, then, it is striking that Michael Fried, the most ardent and influential critic of minimalism—or as he called it, with a force that should now be clear, “literalism”—would understand syntax not only as related to meaning but as its structure. Thus in “Art and Objecthood” (1967, the same year as Smithson’s “Language to be Looked at”), Fried describes the way in which the sculpture of Anthony Caro generates meaning (and thus becomes “a fountainhead of antiliteralist … sensibility”) through its “syntax,” which consists for Fried in “the mutual inflection of one element [of the sculpture] by another.”24 Whereas the literalist work is constructed from “materials [that] do not represent, signify, or allude to anything” (AO, 105), in Caro’s work the “individual elements bestow significance on one another” through their syntactic interrelation (AO, 161). It is this interrelation that produces the work’s meaning, which, for Fried, is something like an instantiation of meaning itself: “It is as though,” Fried says, “Caro’s sculptures essentialize meaningfulness as such” (AO, 162).

We thus find in Smithson and Fried in 1967 something like a discursive externalization and—to use Fried’s term—“hypostatization” of Williams’s contradictory positions in 1947, for and against materiality on the one hand and “meaning” on the other.25 In the first moment, Smithson commits himself to sheer materiality—just as Williams did. And in the second, Fried commits himself to the subversion of materiality through meaning making—as Williams, in his commitment to representation, also did. Indeed, as we saw in the first section, if Williams’s critique of representation was always crucial to his sense of the modern, his refusal of that critique was always at least equally crucial. And, as I’ll try to show in the next section, to understand Williams’s poetics is to understand the centrality to them of his attempt to reconcile these seemingly irreconcilable positions.

III

Williams’s critique of representation originally emerges in its first developed form more than twenty years before the Hartpence story enters his repertoire, in Spring and All (1923). There, the idea that the artwork should be “something not at all a copy of nature, but something quite different, a new thing” (as we saw him put it in his 1952 Autobiography) is already present: Williams throughout the book rails against “the copyist tendency of the arts,”26 a tendency he also refers to variously as “plagiarism after nature” (SA, 35), “illusion” (SA, 45), “likeness,” and “realism.” This last term appears in his famous injunction that the artwork must offer “not ‘realism’ but reality itself,” and Williams repeats this basic formulation—that rather than serve as a representation of the world, the artwork must somehow be the world—several times in Spring and All: “The word must be put down for itself, not as a symbol of nature but a part,” for example (SA, 22); or, again, “It is not a matter of ‘representation’ … but of separate existence” (SA, 45); or, again, regarding “most … writing,” “There is not life in the stuff because it tries to be ‘like’ life” (SA, 61).

Not realism, but reality; not a symbol of nature but a part of nature; not like life but life itself. In all cases, representation ends—but what, exactly, takes its place? We’ve seen that, in the case of painting, the “reality” that supplants representational “realism” is the material reality of “sheer paint.” Yet in Spring and All, the horizon of material realization is not painting but rather a medium even less constrained by the imperatives of representation: music. “Writing is likened to music,” Williams says in the book’s concluding pages. “The object would be it seems to make poetry a pure art, like music” (SA, 91). The way to attain this “pur[ity],” Williams continues, is to divest poetic language of meaning, a project he notes has already been developed by “certain of the modern Russians” (likely the poets associated with zaum such as Aleksei Kruchyonykh) who “would use unoriented sounds in place of conventional words” (SA, 92). More than forty years before Smithson, then, Williams arrives at an entirely Smithsonian approach to writing: though the “modern Russians” isolate language’s sonic rather than visual aspect, they are equally committed to making it, in Smithson’s terms, a “material thing” rather than an “ideal thing.”

But as much as this strategy would appear to successfully neutralize writing’s “copyist tendency,” Williams rejects it in the very next line. “I do not believe that writing is music,” he says. “I do not believe writing would gain in quality or force by seeking to attain to the conditions of music” (SA, 92). Further, Williams argues, writing need not—indeed, cannot—get rid of meanings, per se, at all. Instead, its relation to meanings is what must be changed:

According to my present theme the writer of imagination would attain closest to the conditions of music not when his words are disassociated from natural objects and specified meanings but when they are liberated from the usual quality of that meaning by transposition into another medium, the imagination. (SA, 92)

Here as elsewhere—in Spring and All and beyond—Williams deploys the “imagination” as a kind of theoretical black box to distinguish normal language (tethered to “the usual quality” of “specified meanings”) from poetic language (somehow “liberated” from that quality), as well as to account for the poet’s transformation of the former into the latter. Yet if Williams’s reliance on that black box thus fails to make the force of the distinction clear to us, it is worth noting that he was far from the only figure of the period putting that distinction at the center of poetic concern. Three years after Spring and All, I.A. Richards in “Science and Poetry” (1926) would offer his own account of the way in which poetic language is, as Williams put it, “liberated” from its meaning’s “usual quality.” Whereas “science,” Richards says, aims to convey a clear particular meaning, poetry (“the reverse of science”) is defined by the way it hierarchizes words’ meanings below their sensuous aspects:27 “the sound of the words ‘in the mind’s ear’” (SP, 31) and “the feel of the words imaginarily spoken” (SP, 23). This “sound” and “feel” constitute what Richards calls the “full body” of the words, and it is this body that strikes the reader “even before the words have been intellectually understood” (SP, 23, 30). Much of the “poetic experience” happens at this precognitive stage, and as a result, a “good deal of poetry and even some great poetry” comes to resemble the unoriented sounds of the modern Russians: “the sense of the words,” Richards says, “can be almost entirely missed or neglected without loss” (SP, 31).28 While the deprioritization of meanings does not become outright elimination—meaning can only “almost” be gotten rid of—Richards nonetheless understands that deprioritization as constitutive of poetry as such.

But insofar as the core issue for both Williams and Richards is one of poetry’s relation to meaning, the far more influential account would prove to be that of Richards’s student William Empson, for whom poetry does not attenuate meanings, as for Richards, but rather proliferates them. This proliferation is what Empson famously calls poetry’s “ambiguity,” a term that describes, among other things, the way in which any combination of words in a poem generates a long string of emphases and significances the relevance of which the reader can’t be sure how to assess. As Empson argues in Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), there are in Shakespeare’s line “Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang” (Sonnet 73) a huge number of possible “reasons” for why “the comparison holds,”29 among them:

because ruined monastery choirs are places in which to sing, because they involve sitting in a row, because they are made of wood, are carved into knots and so forth, because they used to be surrounded by a sheltering building crystallised out of the likeness of a forest, and coloured with stained glass and painted like flowers and leaves, because they are now abandoned by all but the grey walls coloured like the skies of winter, because the cold and Narcissistic charm suggested by choir-boys suits well with Shakespeare’s feeling for the object of the Sonnets, and for various sociological and historical reasons …. (ST, 2–3)

Because these reasons “must all combine to give the line its beauty,” Empson says, the “ambiguity” of “not knowing which of them to hold most clearly in mind,” far from being an impediment to understanding the poem, is rather fundamental to “all such richness and heightening of effect.” Indeed, Empson says, ambiguity is a defining feature of the poetic as such: “the machinations of ambiguity are among the very roots of poetry” (ST, 3).

The situation is quite different for prose, where ambiguity does act as an impediment. However, Empson says, most forms of ambiguity turn out to be simply irrelevant to the typical “prose statement.” While a decidedly non-poetic sentence such as “The brown cat sat on the red mat” can with effort be construed as ambiguous (“In a sufficiently extended sense,” Empson notes, “any prose statement could be called ambiguous”), it only possesses “an ambiguity worth notice” if we don’t know what kind of text it comes from: “it might come out of a fairy story and might come out of Reading without Tears,” Empson says, and its “associations” would differ significantly in either case (ST, 1–2). If its context were known, however, all significant ambiguity would disappear; the sentence’s full breadth of meaning would be easily understood.

It Is striking, then, that In 1930, the same year Empson deploys his cat as the exemplary instance of the opposite of poetry, Williams would write a comparable sentence about a cat and, titling it “Poem,” announce it rather as the epitome of poetry:

As the cat

climbed over

the top of

the jamcloset

first the right

forefoot

carefully

then the hind

stepped down

into the pit of

the empty

flowerpot30

It’s not exactly Reading without Tears, but Hugh Kenner reads “Poem” as analogously schematic: rather than primarily concerning itself with conveying meaningful content (as Empson’s cat sentence would if it came “out of a fairy story” rather than a grammar book), the poem asserts its domain as not “the kitchen or the garden but … a language field” (PE, 397). That is, the poem is not “about” a cat, exactly, but rather about the word “cat”—or, more precisely, about the relations between the word “cat” and the words preceding and following it, the “linguistic torsions” through which “this verbal cat” moves that add up to what Kenner calls the poem’s overall “structure” or “pattern” (a pattern that, for instance, sets up the expectation that the opening “As” will give us a second verb following “climbed” but then temporarily thwarts this expectation by introducing “a new substructure” detailing the placement of “forefoot” and “hind”) (PE, 398–99). Just as “a knot is not rope but a pattern the rope makes visible,” so the climb of the cat over the jamcloset renders visible a linguistic knot, and it is the visibility of this knot, rather than any propositional statement about cats, that is the point of the poem (PE, 400).31

Kenner’s word for the character of this linguistic knot is one that is now familiar to us: syntax. Williams’s poem, Kenner says, is one that “fulfills a syntactic undertaking, purely in a verbal field”; the poem’s “pattern,” moreover, is “proffered and conceivable as pure syntax” (PE, 400). This is the crux of what Williams achieves in “Poem,” a point Kenner hammers home in the title of the essay in which this analysis appears: “Syntax in Rutherford.” Yet a key element of that analysis is that, for Kenner, the poem’s foregrounding of syntax is nearly muddied irrevocably—not by any detail of grammar or lineation but rather by the pungency of a particular word, the most conspicuous in the poem: “jamcloset.” For all of Williams’s obsessive refinement toward “pure syntax,” Kenner says, “jamcloset” threatens to overwhelm that refinement with associated ideas and images: unlike “cat,” “forefoot,” and even “flowerpot,” “jamcloset” is “a word bound in place in time,” one that, moreover, “pertains to a half-vanished America with cellars.” This highly evocative quality “might easily tip into nostalgia,” a fatal flaw for a project such as Williams’s. However, Kenner says, “it is interesting that in ‘Poem’ this does not happen,” because Williams manages to make “jamcloset” function as “a term, not a focus for sentiment; simply a word, the exact and plausible word, not inviting the imagination to linger: an element in the economy of a sentence” (PE, 404).

What Kenner points us to here is the fact that Williams’s production of “pure syntax” depends not just on grammatical “torsion” or the interplay of that torsion with inventive lineation, but also on a reconceptualization of individual words and their function as bearers of meaning within the poem. And it is precisely a kind of “nostalgia” that from the beginning constitutes for Williams the biggest threat to the proper functioning of those words—nostalgia not or not just for the historical past evoked by them, but rather for the agglomeration of meanings from words’ own pasts within the poetic tradition, what Williams calls in his essay on Poe from In the American Grain the “pleasing wraiths of former masteries.”32 These wraiths already appear in Spring and All, where he calls them “strained associations” (SA, 22), and he describes them as a kind of historical accrual that eventually degrades poetry into mere cliché: “The rose is obsolete,” as the famous opening line from Spring and All’s seventh poem goes (SA, 30), because it has become laden with these associations, the stuff of “[c]rude symbolism” that would “associate emotions with natural phenomena such as anger with lightning, flowers with love” (SA, 20). And for poetry to achieve its goal of being “not a symbol of nature but a part,” Williams says, there is only one remedy for these associations: “annihilation” (SA, 22).

That annihilation frequently takes, for Williams, the less violent form of “cleaning.” He characterizes Poe, for instance, whose “genius” was impelled by “the necessity of a fresh beginning” (one free of “former masteries”), as crucially offering “a gesture to be clean.”33 In an essay on Marianne Moore, Williams describes her poetry as “wiping soiled words” taken “from greasy contexts”: “each word should first stand crystal clear with no attachments,” he says, and this state is only achieved when the word has been “treated with acid.”34 In an essay on Gertrude Stein, Williams similarly writes of the necessity to “get back to … words washed clean,” but here the thing to be washed off is not associations but the closely related “connotations,” and the mode of washing looks once again like annihilation: “Stein has gone systematically to work smashing every connotation that words have ever had, in order to get them back clean.”35

A precondition to the achievement of “pure syntax” is thus the smashing of all words’ connotations—an “annihilation” that that we can now see is also the annihilation of Empsonian ambiguity as such. Kenner notes that “jamcloset” serves as “the exact and plausible word” for the poem, but for Williams, as we’ve just seen, the exact word is not just the right word: it is also the word from which all connotations have been smashed, leaving only one meaning behind. Williams uses just this conception of exactness in his introduction to The Wedge (1944), where he writes that the poet must assemble words “without distortion which would mar their exact significances.”36 Turning words from bins of varied “associations” into units of “exact” meaning within a tight web of relation, Williams thus defines poetry (and by titling his poem “Poem,” Williams makes this claim precisely for the field of poetry as such) not as the production of ambiguity, per Empson’s claim, but rather as ambiguity’s elimination. For Williams, it is essential that each word bears not “several distinct meanings,” as Empson says, or even “several meanings connected with one another” (ST, 5), but rather the inverse: only one meaning. “Cat” means cat, “forefoot” means forefoot, “flowerpot” means flowerpot—even “jamcloset,” in the end, simply means “jamcloset.”

“Syntax in Rutherford” appears in The Pound Era (1971), but Kenner first wrote it from Santa Barbara (in a “ranch house” without a jamcloset but with, he notes, “‘crawl space’” [PE, 404]) in 1968. We’ve already seen how Smithson, that same year, begins describing syntax as a system of “splits and ruptures,” related to what in Carl Andre’s writing “drive[s] out” “[s]emantics … in order to avoid meaning.” And we’ve also seen how Fried, the year before, characterizes syntax, in the case of Anthony Caro, as constituting “meaningfulness as such.” On the one hand, these two accounts could not be more contradictory: Smithson uses syntax to “avoid meaning,” Fried uses syntax to characterize meaning. On the other, what the two accounts share is the event that occasions them, the very one with which this essay began: the emergence of materiality as a problem in the artwork, something no longer to be taken for granted as the vehicle of the work’s meaning (how paint in a representational painting was simply identical with the representation) but rather something that appears as meaning’s binary opposite. Thus, for Smithson, materiality destroys or absorbs meaning; syntax is “a set of linguistic surfaces that surround the artist’s unknown motives.” For Fried, by contrast, art must “defeat, or allay” materiality through the articulation of meaning—an articulation that the term “syntax” describes (AO, 162). So, while Smithson and Fried are, in an obvious way, completely opposed, their understandings of the terms of the problematic are exactly the same. It is not for nothing that Fried would, some thirty years later, remark that “Smithson’s writings of the late 1960s amounted to by far the most powerful and interesting contemporary response to ‘Art and Objecthood’”;37 nor that Smithson would say, even more strikingly, that “In terms of Michael Fried, even though he’s an adversary of mine, I respect the syntax of his delivery.”38

For Kenner, as we’ve seen, syntax works somewhat differently. Although, as with Fried, syntax becomes the way artistic and interpretive attention is displaced from the words themselves onto the system that interconnects them (cf. Fried, “The mutual inflection of one element by another, rather than the identity of each, is what is crucial” [AO, 161]), the question of materiality as such is not explicitly raised. For Williams himself, however, the displacement from words to relations is wholly a material matter. We recall his announcement, at the beginning of this essay, that the moment of “that is paint” is the “exact place where for us modern art began.” But we recall too Williams’s simultaneous ambivalence about materiality—the way he disparages abstraction and declares that “all painting is representational,” as well as how he excludes the verbal materialism of the modern Russians from his poetics. Thus, for Williams the beginning of modern art is not exactly the emergence of materiality per se, but rather—as for Fried and Smithson—its emergence as a problem, and it is the grappling with this problem that will be the modern artist’s job all the way through to the end. This end, moreover, mirrors the beginning: it occurs, per Fried, precisely when the same materiality that catalyzed the modernist problem is “hypostatized” in literalist postmodernism and the problem disappears.

Yet Williams’s further contribution to this nexus is in bringing Smithson and Fried even more closely together, to encourage a kind of material hypostatization while also insisting on the latter’s subsumption under syntax—or, in Williams’s word for syntax, “design.” It should be no surprise by now that Williams’s most powerful articulation of this conjunction, in Paterson Book V (1971), uses painting for its illustration; what is more surprising is that he focalizes the articulation through the work of that foremost “abstractionist,” Jackson Pollock:

Pollock’s blobs of paint squeezed out

with design!

pure from the tube. Nothing else

is real . .39

On the one hand, we have the moment of materiality at its absolute “pure”-est: paint that not only isn’t brushed into a representation but isn’t brushed at all, retaining its native shape “from the tube” as “blobs”—the painting equivalent of Smithson’s “heap.” On the other hand, the artist mediates the application of these blobs through “design!”; it is not the blobs’ materiality as such that is the point, but rather the conjunction of that materiality with a larger system of relations, the visual syntax of the made painting. Pollock’s work, on Williams’s account, is not about materiality instead of meaning or meaning instead of materiality; rather, it concerns the way the opposition between the two terms is in fact the painting’s structuring principle, not a choice to be made but the field within which choices are made. On this analogy, Williams’s words stripped of all meanings, but one can be understood as the “blobs” of the poem; the freshly cleaned, semantically unitary “cat,” “flowerpot,” and even “jamcloset” are the poem’s raw material, material Williams retains but also relativizes within what Kenner calls the poem’s syntactic “pattern.” To unleash materiality for Williams is not to negate meaning, but to create a circuit from material to meaning—from the blobs to the “design!” that holds them together and back again.

Notes

“The particles of language must be clear as sand.” —William Carlos Williams1

“Language is as primary as steel.” —Robert Smithson2

“The knot is neither hemp nor cotton nor nylon: is not the rope. The knot is a patterned integrity. The rope renders it visible.” —Hugh Kenner3

I

In the late 1940s, William Carlos Williams’s understanding of modern art suddenly became inseparable from an origin story about it. Regularly featuring the anecdote in his lectures of the period, he would just as regularly mention how fond he was of telling it. “I have told this story often before,” he says in a 1952 speech published as “The American Spirit in Art,” “but it bears repeating”:

Alanson Hartpence, who used to be with the Daniel Gallery, once, during his boss’s absence, had one of the gallery’s best patrons there looking at a picture. The estimable lady admired one of the paintings and seemed about to buy it—or at least she was leaning that way.

But Mr. Hartpence, she said, what is all this down here in this left-hand lower corner? […]

That, said Hartpence, leaning closer to inspect the place, that, Madame, he said, straightening and looking at her, that is paint.

He lost the sale.

But that is the exact place where for us the virus first bit in. That is the exact place where for us modern art began.4

The story construes the birth of “modern art” as first and foremost the end of representation—what the customer is trying and failing to get an answer about—and the beginning of something else: “paint.” As Williams writes in his Autobiography, just after telling a version of the story, “it is NOT to hold the mirror up to nature that the artist performs his work. It is to make … something not at all a copy of nature, but something quite different, a new thing.”5 That “new thing,” the story says, is painting’s presentation of paint as such, disburdened of its representational responsibilities and finally able to be seen by and for itself. And this presentation, in turn, marks the beginning of a new aesthetic regime, one into which the customer, with her attachment to what Williams calls art’s “medieval and classic criteria,” cannot enter (RI, 218). If, as Henry Sayre puts it, “Hartpence’s modernism” consists in his “willingness to give up the necessity of representation … to forego the objective image and to interest himself instead in paint itself as medium,” his customer’s pre-modernism is her refusal to do the same—hence Hartpence “los[es] the sale.”6

And yet the displacement of the representational by the material that characterizes “modern art” does not, on Williams’s account, mean that art is now “‘about’ nothing other than itself,” as Terrence Diggory has put it.7 To the contrary, as Williams tells us a moment later in “The American Spirit,” the modern artist doesn’t “paint a picture or write a poem about anything” (RI, 218). When the painting no longer represents—is no longer of something—it is also no longer “about” something; “meaning” and “subject matter”—Williams’s terms—are revealed to be vestiges of representation and eliminated along with it. Thus, when he tells the Hartpence story in a 1947 speech, he does so as a corrective to “the tendency everywhere … to overload the verse with ‘meaning’”;8 similarly, in “The American Spirit,” he concludes that, after Hartpence, “You do not select subjects anymore; to classify poems or pictures by their subject matter is today a little childish” (RI, 218). So, it’s not that paint in “modern art” takes itself as its “subject”—that paint “means” paint or is “about” paint. Instead, as Diggory puts it, a “crucial tenet of William’s aesthetic” is that “paint is paint” (EP, 4).9

The stakes of this opposition, not just between materiality and representation but also between materiality and “subject matter,” “meaning,” or what the artwork is “about,” will become clearer as we go on. But it is significant that if the Hartpence story depicts that opposition as a confrontation between two historically specific perspectives—between the pre-modernism of the customer’s commitment to representation and the modernism of Hartpence’s commitment to materiality—a related confrontation can be seen in the history of Williams’s interest in the story itself. As Diggory points out, while the story is set in the 1910s (Hartpence told it to Williams in 1918, according to William Marling10), Williams appears to only have begun telling it in the late 1940s—by which time the world of advanced art had evolved considerably. Diggory suggests that the most relevant change for Williams over that period was the post-war emergence of an ethical discourse around art. “In the years following World War II,” he writes, “the question of aesthetic autonomy, or self-referentiality … was reposed in ethical terms that have continued to fuel critical debate since that time” (EP, 4). Thus, on Diggory’s account, while the Hartpence story had only produced an aesthetic position when it took place in 1918, by the 1940s it could be understood as embodying an ethical one: when paint is allowed to simply be paint, Diggory says, the medium is “preserv[ed],” an ethically salutary act (EP, 5). When paint is wielded in service of representation, by contrast, used “to refer to something other than itself,” “violence” is perpetrated against it (EP, 6). The way to aesthetically resist violence then is to maintain “respect for material,” an ethos that the Hartpence story, according to Diggory, signally announces (EP, 4).

Yet there are also purely aesthetic reasons why Williams may have suddenly taken such a keen interest in the story twenty-five years after its occurrence. To begin with, the transformation it illustrates—the displacement of representation by materiality in the work of art—was far from complete in 1918. To the contrary, as Williams states, it was only just beginning (the story is where “modern art began”), which is why it’s still completely reasonable for the customer in 1918 to want to see the painting as a representation of something—indeed, most of the painting is a representation of something. The conceptual force of Hartpence’s declaration derives precisely from its abrupt—and, to the customer, unreasonable—rejection of the prevailing paradigm.

By the late 1940s, however, when Williams begins telling the story, the displacement of the representational by the material was beginning to reach what would have looked to him like its logical endpoint—a development that Williams seems at various moments to have emphatically disapproved of. At the vanguard of this development was Jackson Pollock, a figure who would, as we’ll see, eventually become significant for Williams’s poetry. As late as 1945 Pollock’s work was, like the Daniel Gallery painting, still capable of powerfully soliciting Hartpence’s customer’s question. Untitled, for instance, is replete with abstract elements, making its object of representation hard to decipher (fig. 1). And yet an object of representation is nonetheless suggested and in fact (according to the Museum of Modern Art, which owns the drawing) can be read: Untitled, they say, depicts “[t]wo totemic figures fac[ing] each other, the right one with its leg bent along the bottom of the sheet.”11 The drawing can thus still be said to be “of” something even as it pushes depiction to the breaking point, and the tension the Hartpence story evokes thus remains in play. The customer (or a viewer at MoMA) would be getting at that tension by asking “what is all this?” (because it’s hard to tell); Hartpence (or an art critic) would be deepening that tension by answering, “that is paint.”

But by 1947—the same year that Williams first told the Hartpence story in print—Pollock had begun making his drip paintings, works in which the last suggestion of representation had been abolished. Of these paintings, such as Full Fathom Five from that year, the customer’s question could no longer reasonably be asked, because “that is paint”—thirty years earlier a radical alternative to the expected answer—had suddenly and conspicuously become the only answer (fig. 2). Whereas the lines of paint in Untitled tend to depict shapes and figures, however abstract, in Full Fathom Five they are ostensibly untethered from any depictive function at all. Thus, the tension between representation and materiality—the possibility, still present in Untitled, that paint could be something other than paint, without which Hartpence’s declaration would have been merely tautological—had by 1947 given way to a materiality that was both conceptually and literally total. Or, put differently: what in 1918 (or even 1945) had been confined to the “lower left-hand corner” of the painting had by 1947 expanded to fill the whole thing.

One way to describe this would be to say that modernism—understood in the terms of the story as the replacement of the representational by the material—had triumphed. Hartpence’s answer to the customer’s question had been art historically vindicated and thereby finalized. But from another perspective, we can see that the finality of that answer had in fact neutralized the tension that produced the question in the first place: when it would no longer occur to anyone to ask, “what is all this?”, “that is paint” loses its force as a radical aesthetic position. And from this perspective, what briefly appeared to be modernism’s triumph begins to look to Williams more like its dead end. It is this version of events that helps us begin to make sense of another of Williams’s texts from the period, an essay on the painter Emanuel Romano he wrote in 1951 while preparing the “American Spirit” speech—a simultaneity that is startling when one comes across passages like the following:

Modern painters … have been afraid of the horrible word “representational”; they have run screaming into the abstract, forgetting that all painting is representational, even the most abstract, the most subjective, the most distorted. The only question that can present itself is: What do you choose to represent?12

This is a far cry, of course, from Williams’s assertion in “The American Spirit” that “you don’t paint a picture or write a poem about anything.” And indeed, his championing of the “representational” here would seem to refute the most basic premise of the Hartpence story itself. “What do you choose to represent?” is, as we’ve seen, precisely what the customer is asking; if that question is, on Williams’s own account, “The only question that can present itself,” she would seem to be more the anecdote’s hero than its villain, with Hartpence in turn playing the role of the hysterical modern running “screaming into the abstract”—obviously a complete reversal of Williams’s basic position as we’ve so far understood it.

This contradiction is further sharpened in Williams’s opposing accounts of Cézanne, one of the most important figures for the poet throughout his career and one who often appeared in close proximity to recitations of the Hartpence story. In his Autobiography, just after telling the story, Williams says that “Cézanne is the first consciously to have taken that step” (A, 240); in “The American Spirit,” similarly, the story reveals “the essence of Cézanne” (RI, 218). Toward the Autobiography’s end, Williams recalls a speech in which he had described “the years when the painters following Cézanne began to talk of sheer paint: a picture a matter of pigments upon a piece of cloth stretched on a frame.” (In the next line he says, right on cue, “I told them the Hartpence story” [A, 380].) Yet in the Romano essay, just after the above-cited critique of the “modern painters,” Williams counts Cézanne among the masters of representation—he was, Williams says, “a great realist” (RI, 197).

Moments like these lead Sayre to rightly note that “Even as [Williams] championed abstraction in the poem and in the painting, he steadfastly believed in the necessity of objective representation” (TI, 129).13 But this contradiction is also far from idiosyncratic to Williams. I want to suggest, rather, that it can be better understood as belonging to the logic of modernism itself—a logic that Williams, perhaps more than any of his contemporaries, nonetheless embodied in his conflictual back and forth on these questions. On the one hand, the eruption of materiality into the representational artwork so vividly illustrated by the Hartpence story will put modernism into motion—it will be “the exact place … modern art began.” On the other, the totalization of this materiality will threaten, as we’re beginning to see, to spell modernism’s end. This essay’s third section will show how Williams forges his poetics within the immensely pressurized conceptual space between these two moments—an achievement Hugh Kenner’s writing on Williams uniquely enables us to grasp. But first, we begin at the end.

II

“There is an objectivity to the obdurate identity of a material,” writes Donald Judd in “Specific Objects” (1965), thus formulating one of the central tenets of the artistic movement that would be known as minimalism.14 Judd in that essay enumerates the common features of “the new three-dimensional work” (DJ, 135), a form he distinguishes from sculpture in part on the basis of sculpture’s subordination of material “identity” to other ends. These ends, for Judd, are primarily the anachronisms of “imagery” and “salient resemblances to other visible things” (DJ, 138): in “earlier work,” for instance, “imagery” leaves the “material” in which it’s “executed” “neutral and homogeneous” (DJ, 143); in work that “imitat[es] movement,” similarly, “the material never has its own movement” (DJ, 138). In the “new work,” by contrast, materials are permitted to be “specific.” And that means, in a tautology characteristic of Judd, that “Materials … are simply materials” (DJ, 143).

The tautology is also, of course, reminiscent of Hartpence—both in its structure (materials are materials, just as paint was paint) and in terms of what it rejects: representation, the “mirror up to nature” form of art that Williams, in his Hartpencian mode, casts aside. And although Judd takes additional pains in “Specific Objects” to argue the new work’s differences from (and superiority to) painting, those differences are nuanced by his famous qualification that “The new work obviously resembles sculpture more than it does painting, but it is nearer to painting” (DJ, 138). This nearness would consist, for Judd, in painting’s having pushed materiality as far as it could go in the “rectangular plane” before exhausting that form (“A form can be used only in so many ways,” he writes [DJ, 136]); the “new work,” in a sense, would simply continue painting’s materialist trajectory out into three dimensions, thereby doing what sculpture had failed to do. In that respect, Judd counted one painter as an especially crucial precedent, one to whom he returns in his writings again and again: Pollock. “I think Pollock’s a greater artist than anyone working at the time or since,” Judd writes in a 1967 essay, explaining that that greatness is in large part due to the painter’s “use” of “paint as material.”15 “This use,” Judd says, is “one of the most important aspects of Pollock’s work,” and it is grounded in Pollock’s allowing his paint to retain all of its material specificity as it’s applied to the canvas (DJ, 191). “The dripped paint in most of Pollock’s paintings is dripped paint,” Judd writes in another characteristic, and even more Hartpencian, tautology. “It’s not something else that alludes to dripped paint” (DJ, 191–92).

Paint does, however, exhaust its usefulness. And the impersonal, industrial materials often used by the artists associated with minimalism—“formica, aluminum, cold-rolled steel, plexiglas, red and common brass, and so forth,” as Judd lists in “Specific Objects”—seemed to Judd particularly suitable for an art that would push the materialist tautology originated by Pollock to the next level (DJ, 143). Yet the same materialist aesthetic that attracted minimalist artists to the “obdurate” qualities of aluminum and brass would draw others, such as Judd’s younger colleague Robert Smithson, also in the exact opposite direction—not just to the relative straightforwardness of materials that seemed to naturally resist the tendency toward “allu[sion],” but also, more paradoxically, to the most allusive medium of all, and the one with which Williams was most preoccupied: language.

Thus, in 1967 (the same year that Judd published his essay on Pollock), Smithson co-organized a show for the Dwan Gallery on the theme of language, titled “Language to be Looked at and/or Things to be Read.” In the short but complex press release for the show, Smithson begins some preliminary theorizing toward the notion of a radically materialized language.16 Distinguishing between “literal” and “metaphorical signification,” Smithson attributes a quasi-magical power to the former when the latter is done away with: “Literal usage becomes incantatory when all metaphors are suppressed” (LL, 61). Yet eliminating metaphor, he determines, is not enough, since metaphoricity is revealed to infect literal speech all the way down. “[D]iscursive literalness is apt to be a container for radical metaphor,” Smithson writes. “Literal statements often conceal violent analogies” (LL, 61). It will thus take actual material literality, not merely linguistic literality, to get a truly materialist version of language: in the ideal scenario, “language is … not written” at all, but “built” (LL, 61). Smithson gestures further toward this deeper materialism by signing his name “Eton Corrasable”—a reference to Eaton’s Corrasable Bond, a then-popular erasable typewriter paper. Yet, apparently feeling the need to make the point more strongly (and clearly) five years later, Smithson would append a one-line postscript to the text in 1972. It reads simply, “My sense of language is that it is matter and not ideas—i.e., ‘printed matter’” (LL, 61).

We can see Smithson developing toward this highly refined version of the position in the intervening years between show announcement and postscript. “[L]anguage and material … are both physical entities,” he says in a 1969–70 interview. “I’m concerned with the physical properties of both language and material, and I don’t think that they are discrete” (RS, 208). For “language” and “materials” not to be “discrete,” for both to have as their only relevant characteristics their “physical properties,” is, for Smithson, to conceive of language in much the same way that Hartpence conceived of paint: not as something representational, something standing in for something else, but as something—in Smithson’s word—“primary” (RS, 214). And for language to be “primary,” just another kind of “material,” is for it to not belong to the realm of the “ideal”: “I don’t think that language … is an ideal thing,” he says in the same interview, “but that it’s a material thing” (RS, 213).

Teasing out the implications of a language construed as material but not ideal, Craig Dworkin puts Smithson’s 1972 “matter and not ideas” addendum next to Mallarmé’s famous quip about poetry to his friend Degas:

Smithson’s formulation, tellingly, recalls Stéphane Mallarmé’s sense of poetry itself. Responding to Edgar Degas’s complaint that it was easy to come up with good ideas for poems but hard to arrange particular words, Mallarmé wrote back to his friend: “Ce n’est point avec des idées, mon cher Degas, que l’on fait des vers. C’est avec des mots [My Dear Degas, poems are made of words, not ideas].”17

On the face of it, the parallel makes sense: in comparing Smithson and Mallarmé, Dworkin renders the former’s “matter” as analogous to the latter’s “words,” the two terms united in their opposition to “ideas.” Yet if Mallarmé produces a distinction between “words” and “ideas,” it is not to purge language of any “ideal” dimension whatsoever; the words, even in a Mallarmé poem, still signify. For Smithson, on the other hand, they don’t. If, as Smithson says, “a rock would be compared to a word,” making them “interchangeable” because “they are both material,” we have gone quite a distance from the kind of “words” Mallarmé is talking about (RS, 209). Indeed, the whole force of Smithson’s identifying language with “matter” is, in a sense, not to link “matter” with “words” but precisely to open a conceptual gulf between them and thus to work exactly against what Mallarmé says to Degas: for Smithson, “words” are not opposed to “ideas” because what Mallarmé (and everyone else) means by “words” are indelibly permeated by “ideas.” For a word to be a “physical entity,” by contrast, is for it to functionally cease being a word: as Smithson says in the “Language to be Looked at” text, “the ‘object,’ takes the place of the ‘word’” (LL, 61).

Put more simply, Smithson and Mallarmé can’t possibly agree with one another because a poem written with “words” as Smithson conceives of them—words that are “built” on the page and “not written”—would no longer be a poem. Instead, it would be something more like a drawing. And indeed, as Dworkin himself argues in a separate essay, Smithson makes just this point in his 1966 drawing A Heap of Language (fig. 3). The work literalizes the title: cramped words in Smithson’s cursive hand—words that Dworkin informs us are culled from the entry for “language” in Roget’s Thesaurus—are piled into a loose pyramidal form on numbered graph paper.18 But in comparing Smithson’s writing to the source material, Dworkin observes that the transcription is spotty, full of omissions and substitutions. There is, he says, a logic to be discovered in Smithson’s transcription process, but it is a logic that issues from the physical shape of the heap rather than from anything having to do with the meanings of the words themselves. “In all cases,” Dworkin explains, “the deviations [from the original text] were made to maintain the even incline of the heap. Sloping at about forty degrees, the text’s margin mimics the angle of repose of moderately damp soil, sandy gravel, or crushed asphalt”19—the kinds of materials Smithson often used in his three-dimensional work. In this way, then, A Heap of Language shows us what a totally materialized language actually looks like: in place of the meaningful relations between words that would involve them in “ideas” (and thus make them language “to be read”), there are only the “material” relations that pile them into a heap—a “language to be looked at.”20

What A Heap of Language adds to Smithson’s statements about language is thus to show how treating language as “a material thing” rather than “an ideal thing” involves rethinking not just words themselves but also the way they are organized and beginning to conceive of them, in the terminology Smithson adopts from linguistics, as devoid of “semantics”—language’s meaningful dimension—yet still ordered by a “syntax”—language’s non-meaningful structuring principles. While the words appear to have neither a semantic nor syntactic relation to one another, their purely material relations (the imagined gravity that holds them together in a heap) are part and parcel of how Smithson understands the syntactic. Writing of Carl Andre’s prose style in 1968—in a paragraph that itself serves as a capsule summary of Smithson’s theory of language—Smithson says that “Semantics are driven out of his language in order to avoid meaning,” with “meaning” here associated with the “ideal” realms of “thoughts” and “reason” (“Thoughts are crushed into a rubble of syncopated syllables,” he writes of Andre’s prose. “Reason becomes a powder of vowels and consonants”).21 Judd’s writing, meanwhile, is equally material for Smithson (it is a “brooding depth of gleaming surfaces”) and thus equally devoid of semantics, yet that very material meaninglessness—characterized by Smithson, in a favorite word, as an “abyss”—is brought under the heading of syntax: “Judd’s syntax is abyssal—it is a language that ebbs from the mind into an ocean of words” (MOL, 80).

If semantics is identical with meaning, then, Smithson defines syntax precisely by its non-identity with meaning—a point he repeats again and again. Whereas he characterizes semantics as the verbal manifestation of “thought” and “reason” (and thus as something for Andre to “drive[] out”), “each syntax” in an artist’s writing “is a … set of linguistic surfaces that surround the artist’s unknown motives” (MOL, 82), the meaningfulness of “motives” entirely delinked from—more, obscured by—the material quality of syntactic “surfaces.” In his well-known essay, “A Sedimentation of the Mind,” also from 1968, Smithson associates “words” with “rocks” on the grounds that both “contain a language that follows a syntax of splits and ruptures”—a syntax similar, perhaps, to that which breaks up a thesaurus entry in order to pour it into a heap.22 Once again, syntax not only has no relation to meaning, but it also comprises the active impediments to meaning of “splits” and “ruptures” and, a moment later, “fissures”: “The names of minerals and the minerals themselves do not differ from each other, because at the bottom of both the material and the print is the beginning of an abysmal number of fissures.”23 Unlike semantics, syntax is no threat to the meaninglessness of materiality. For Smithson, syntax is simply materials’ “abysmal” structure.

For all of Smithson’s insistence on the non-meaningfulness of syntax, then, it is striking that Michael Fried, the most ardent and influential critic of minimalism—or as he called it, with a force that should now be clear, “literalism”—would understand syntax not only as related to meaning but as its structure. Thus in “Art and Objecthood” (1967, the same year as Smithson’s “Language to be Looked at”), Fried describes the way in which the sculpture of Anthony Caro generates meaning (and thus becomes “a fountainhead of antiliteralist … sensibility”) through its “syntax,” which consists for Fried in “the mutual inflection of one element [of the sculpture] by another.”24 Whereas the literalist work is constructed from “materials [that] do not represent, signify, or allude to anything” (AO, 105), in Caro’s work the “individual elements bestow significance on one another” through their syntactic interrelation (AO, 161). It is this interrelation that produces the work’s meaning, which, for Fried, is something like an instantiation of meaning itself: “It is as though,” Fried says, “Caro’s sculptures essentialize meaningfulness as such” (AO, 162).

We thus find in Smithson and Fried in 1967 something like a discursive externalization and—to use Fried’s term—“hypostatization” of Williams’s contradictory positions in 1947, for and against materiality on the one hand and “meaning” on the other.25 In the first moment, Smithson commits himself to sheer materiality—just as Williams did. And in the second, Fried commits himself to the subversion of materiality through meaning making—as Williams, in his commitment to representation, also did. Indeed, as we saw in the first section, if Williams’s critique of representation was always crucial to his sense of the modern, his refusal of that critique was always at least equally crucial. And, as I’ll try to show in the next section, to understand Williams’s poetics is to understand the centrality to them of his attempt to reconcile these seemingly irreconcilable positions.

III

Williams’s critique of representation originally emerges in its first developed form more than twenty years before the Hartpence story enters his repertoire, in Spring and All (1923). There, the idea that the artwork should be “something not at all a copy of nature, but something quite different, a new thing” (as we saw him put it in his 1952 Autobiography) is already present: Williams throughout the book rails against “the copyist tendency of the arts,”26 a tendency he also refers to variously as “plagiarism after nature” (SA, 35), “illusion” (SA, 45), “likeness,” and “realism.” This last term appears in his famous injunction that the artwork must offer “not ‘realism’ but reality itself,” and Williams repeats this basic formulation—that rather than serve as a representation of the world, the artwork must somehow be the world—several times in Spring and All: “The word must be put down for itself, not as a symbol of nature but a part,” for example (SA, 22); or, again, “It is not a matter of ‘representation’ … but of separate existence” (SA, 45); or, again, regarding “most … writing,” “There is not life in the stuff because it tries to be ‘like’ life” (SA, 61).

Not realism, but reality; not a symbol of nature but a part of nature; not like life but life itself. In all cases, representation ends—but what, exactly, takes its place? We’ve seen that, in the case of painting, the “reality” that supplants representational “realism” is the material reality of “sheer paint.” Yet in Spring and All, the horizon of material realization is not painting but rather a medium even less constrained by the imperatives of representation: music. “Writing is likened to music,” Williams says in the book’s concluding pages. “The object would be it seems to make poetry a pure art, like music” (SA, 91). The way to attain this “pur[ity],” Williams continues, is to divest poetic language of meaning, a project he notes has already been developed by “certain of the modern Russians” (likely the poets associated with zaum such as Aleksei Kruchyonykh) who “would use unoriented sounds in place of conventional words” (SA, 92). More than forty years before Smithson, then, Williams arrives at an entirely Smithsonian approach to writing: though the “modern Russians” isolate language’s sonic rather than visual aspect, they are equally committed to making it, in Smithson’s terms, a “material thing” rather than an “ideal thing.”

But as much as this strategy would appear to successfully neutralize writing’s “copyist tendency,” Williams rejects it in the very next line. “I do not believe that writing is music,” he says. “I do not believe writing would gain in quality or force by seeking to attain to the conditions of music” (SA, 92). Further, Williams argues, writing need not—indeed, cannot—get rid of meanings, per se, at all. Instead, its relation to meanings is what must be changed:

According to my present theme the writer of imagination would attain closest to the conditions of music not when his words are disassociated from natural objects and specified meanings but when they are liberated from the usual quality of that meaning by transposition into another medium, the imagination. (SA, 92)