Another way of putting this is to say that the violence of the frame consists above all in making our lives as irrelevant as hers, and it’s in this indifference to our particularity (this allegorizing of its irrelevance) that I locate the politics of Kydd’s work.

We are concerned with the problem of securing meaning against the ideological horizon of a fully market-saturated society. Meanings circulate or fail to circulate, compel or fail to compel. Success in the former, which is easily quantifiable, does not guarantee success in the latter, which is not.

When Max Beckmann (1884-1950) painted The Synagogue in 1919, he could not have anticipated the ways in which it would come to be viewed and interpreted. His critics were the first to weigh in after World War I with poetic analyses. Subsequent viewers – including museum and municipal officials – placed less emphasis on the painting’s purely formal values. Since 1945, The Synagogue’s prophetic quality and historical function as well as its political uses and pedagogical applications have shaped its reception. Eschewing an interpretive mastery of the painting, this essay considers the viewer’s varied response to Beckmann’s picture as evidence of its radical authenticity.

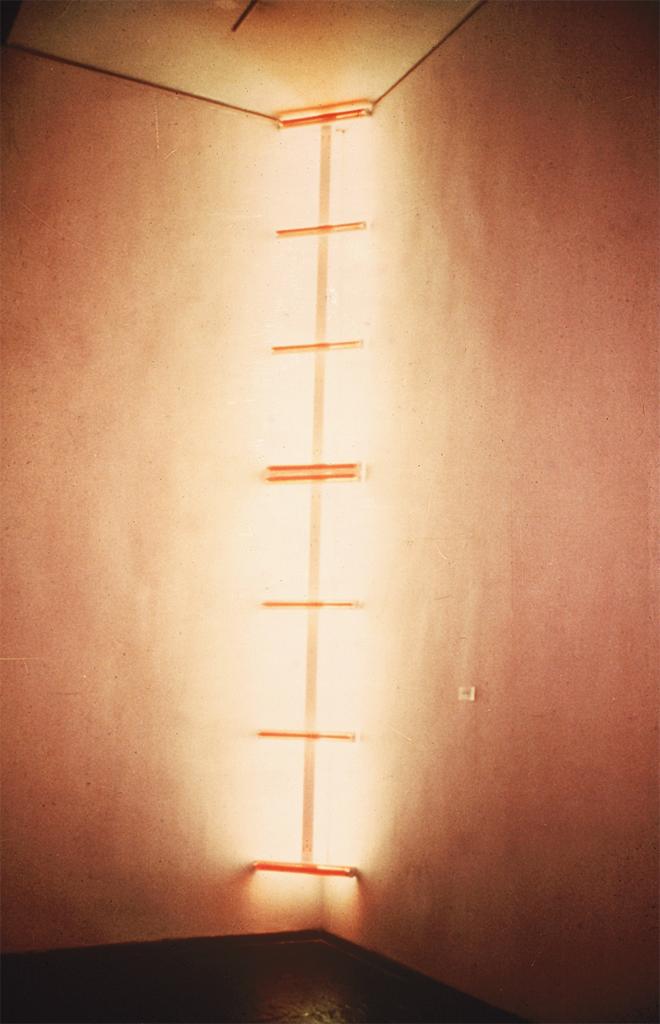

All fluorescent bulbs will eventually go out; only Flavin’s intentions can make some of them also be about the fact that they will eventually go out. All of us may think of the ephemeral when we look at a fluorescent bulb flickering; only the belief that this (or something else) is what Flavin meant us to think turns our responses into interpretations.

As I try to make this out I may find myself hesitating among several possibilities: that Manet simply took advantage of the earlier painting’s meaninglessness; that he was in some way actively interested in the palpable discontinuity within the painting between artist’s intention and unrealized meaning; that his own painting stands as a reading of Velázquez’s, where reading means something distinct from but not without relation to interpretation.

BY M.D. Garral

Meaning, no less than intention, matters. But to the extent it isn’t all or above all what interpretation, indeed appreciation, of an artwork aims at, or is in any event of a different, less linguistic order than those in search of it tend to suppose, then, their intentions notwithstanding, in a relevant sense both intentionalism and the do-or-die debate about it might not be all that any more than where it’s at.

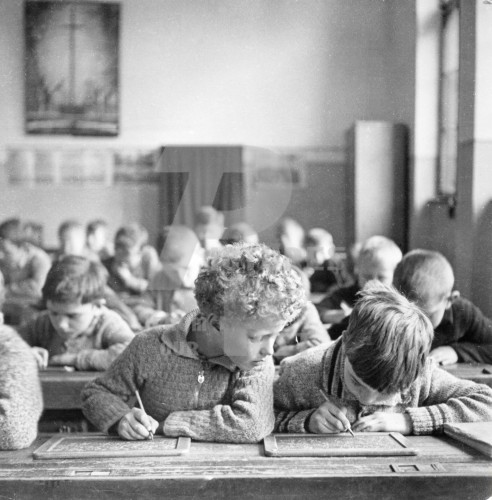

This is what we might say about Philosophical Instigations, a collection of slips of paper in the nachlass of an important philosopher, Wittstein, that were taken to be paragraphs he wrote as expressions of a new philosophical theory, but which in fact were his collection of student in-class responses to the repeated assignment, “Write something short and interesting about language.”

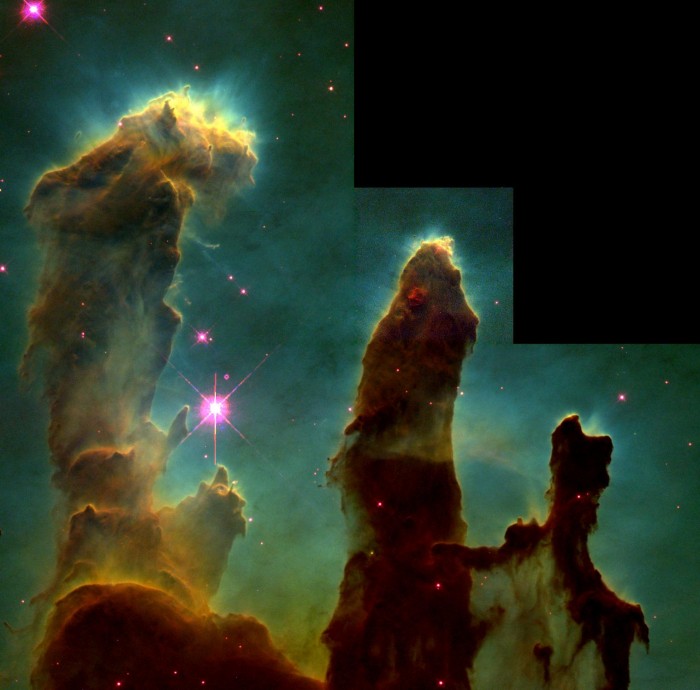

In these terms, the account of the making of this photograph is a description of the more or less necessary historical conditions from which it (and many others) arose. These conditions did not determine the image, rather they made the image possible, and they made it possible in terms very different from those that made other artifacts possible. Every artifact has arisen and arises from such a concrete set of possibilities, and all of these sets of possibilities have their own histories.

Whatever previous ages might have fancied, we are wise enough to know that the work of art is a commodity like any other. Chances are that we don’t have any very clear idea what we mean by that. Marx, however, does.

The critic can embrace aesthetic attention to the specifics of “how” the work unfolds and still avoid any trace of formalism: art is a means of combining and re-orienting imaginative spaces that attach us to features of the world.