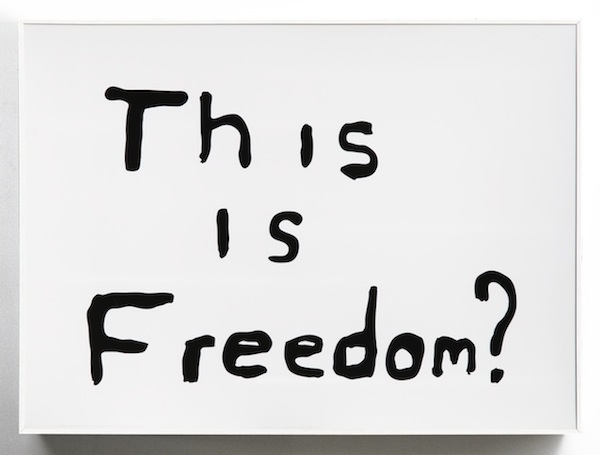

When Exclusion Replaces Exploitation: The Condition of the Surplus-Population under Neoliberalism

The central problem with which we are confronted today, in other words, may be less the conflict between labor and capital, and more, as Margaret Thatcher put it, the antagonism between a privileged “underclass” with its “dependency culture” and an “active” proletariat whose taxes pay for a system of “entitlements” and “handouts.”