The Political Ontology of Unemployment: Why No One Need Apply – Reply to Zamora

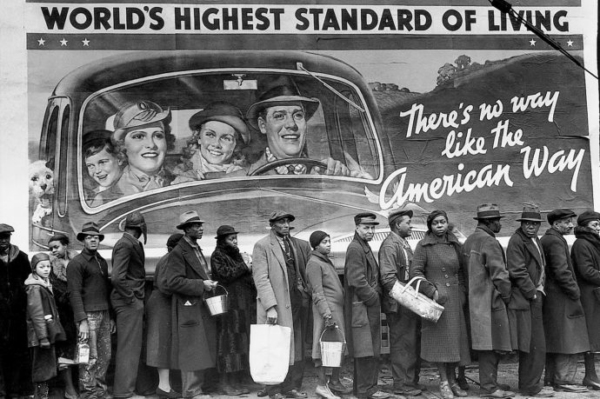

Once the door had been opened onto the phenomena of the chronically unemployed, it appeared there was no closing it. Which is to say, even though the intervening period—at least between 1945 and 1979—was characterized by something wildly different than rank unemployment, nothing about this fact altered the vision of revolutionary progress centered on the figure of the precariat. It would be fairer to say exactly the opposite. The “affluent society,” as Kenneth Galbraith described it in 1958, was the source of endless lament on the Left (the Right’s attitude toward the growing equality in wealth is another, but related, story).