In recent years, political debates over American crime policy have become centered on whether prisons should aim to rehabilitate rather than punish offenders. While rehabilitative discourse appears to be a progressive alternative to punitive politics, I argue that rehabilitative ideology is built on theoretical premises that justify punitive politics. By conceptualizing criminality within individualistic and deterministic frameworks, the rehabilitative ideal of American criminal justice depicts crime as a function of individual-level faults rather than as symptoms of the deeper social and political inequalities that shape the class profile of the prison population. When criminality is viewed as a function of defects and deficiencies entirely rooted in the person, criminality can only be cured through individual level responses rather than more systematic structural reform.

Today, race performs the function of suppressing working-class politics in the interests of both white and black political elites who are equally committed to capitalist class priorities as defining the boundary of political possibility.

BY Jan Sowa

It’s here again, that we encounter the basic flaw of liberal common sense, with its fixation on cultural factors and the importance of ethos. What they neglect is an element that was entirely wiped out of both public and academic discourse in Poland as well as elsewhere, for example, in the US: the issue of class and its indelible materialist component. Populism is a kind of displaced and perverted class revolt. It derives from an oppression of double kind: material for the poor and symbolic for the lower-middle class.

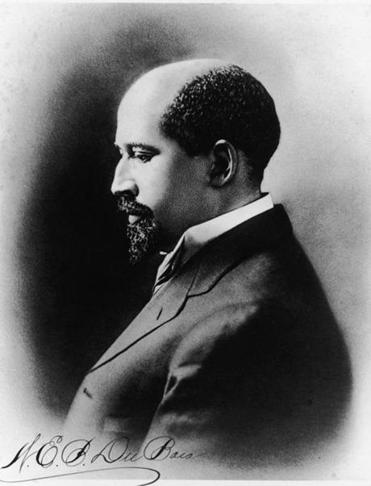

Since the emergence of what has been known as “whiteness studies” in the early 1990s, proponents of the view that the white working class in the United States rejects a class-based politics in favor of commitment to white supremacy have cited W.E.B. Du Bois’s reference in Black Reconstruction In America to a “psychological wage” that whiteness offers as supporting that view and, by extension, the necessity that combating racism and white supremacy takes priority over struggle against capitalist inequality.

The politics that inform these actions, where not entirely opaque, are based on a semi-spiritual belief that the right recipe of symbolism, passion, and powerful visuals will inspire significant political action that will alter the course of this or that unjust policy or state of affairs. Organizers want to inspire the people who view their protest images on their phones.

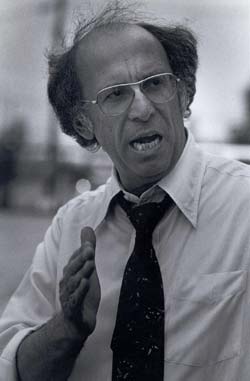

BY James Oakes

The social bases of political conflict thus erased, consensus historians go on to suppress the significance of antislavery politics, even to the point of denying that politics played any role in whatsoever in the destruction of slavery. These crucial erasures are once again explained by reference of a broad political consensus—not the liberal consensus of Hofstadter and Hartz, but the smothering, all-consuming consensus in favor of “white male supremacy.” It’s still consensus history; it’s just a different consensus.

BY Mark Dudzic

The “white working class,” like the “black community,” is an abstraction that does not exist anywhere in the real world. The U.S. working class is broad and diverse. It’s not even all that white any more and certainly not all that male. Its conditions are determined by its position within a political economy but, like everyone else, the experience and consciousness of individual workers is formed by a whole series of contingent relationships and experiences. The recent use of the trope of the angry white working class attempts to extract white workers from these class dynamics and present them as a demonized and marginalized natural group.

BY Leslie Lopez

It might be a huge stretch for some anti-racists to view Trump voters as something other than “deplorables,” or, rich, white, racists—but, the hope with this case study is that we might stop and reflect on who gains when we write off not just half the country but a large portion of the working class as racists.

The most immediate challenge we face now is to prepare for what is going to be the political equivalent of a street fight that we’ll have to wage between now and at least 2018 just to preserve space for getting onto the offensive against the horrors likely to come at us from Trump, the Republican congress, and random Brown Shirt elements Trump’s victory has emboldened. At the same time, however, we need to reflect on the extent to which progressive practice has absorbed the ideological premises of left-neoliberalism.

Contrary to how he was portrayed in the mainstream media Trump did not talk only of walls, immigration bans, and deportations. In fact he usually didn’t spend much time on those themes. Don’t get me wrong, Trump is a racist, misogynist, and confessed sexual predator who has legitimized dangerous street-level hate and his administration will almost certainly be a terrible new low in the evolution of American authoritarianism. But the heart of his message was something different, an ersatz economic populism that spoke directly, clearly and emotionally to legitimate working class concerns.