It often appears that academics and associated cultural workers take a critical view of everything except their own place in the world. We hear a great deal about museums “incorporating” critique, but nothing absorbs opposition like the Ph.D. machine, where every cultural infraction becomes material for a career. Similarly, historians of art have paid attention to images of labourers and capitalists, but given remarkably little consideration to their own class fraction—the petite bourgeoisie.1 This grouping, called here the Professional-Managerial Class (PMC), is all around us, yet it goes unnoticed; it is a visible-invisible object.2 Things have changed somewhat in recent times with the debate on affective labour and the precarious situation of cultural workers. Blending post-Workerist ideas with the claims of Boltanski and Chiapello in The New Spirit of Capitalism, some art-activists claim that the experience of “flexible” intern labour provides a model for the subjectivised or affective character of modern work.3 This focus on precarious labour, particularly union organising among low-paid and casualised workers, is to be welcomed, but if the class location of artists, academics and curators was formerly a blind spot, it is now inflated into the grounding condition of the contemporary economy and it is the social structure of capitalism, rather than the position of academics, that becomes invisible. The approach of cultural intellectuals to their own class position seems to be all or nothing.

My consideration of the Professional-Managerial Class will be historical in character, but in returning to the 1970s and looking again at the vivid debate from that time on the PMC I aim to highlight aspects of the analysis that have been overlooked in the recent rediscovery of the concept by the U.S. Left.4 Principally, this entails drawing attention to a structuring contradiction within the PMC bloc. The ideas arising from that period discussion might be usefully employed to examine the work of a range of artists, but Allan Sekula stands out as an artist-intellectual directly engaged with this question. In the mid-1970s, like Barbara and John Ehrenreich, who sparked the initial interest in the PMC, Sekula was a member of the New American Movement, a multi-tendency revolutionary-socialist organisation.5 His personal library includes the issues of Radical America containing the essays by the Ehrenreichs, which gave impetus to this line of analysis and, while this does not prove that he paid any particular attention to these texts, other books in his possession show he studied the issues they raised.6

Sekula was exceptionally well read across a wide range of topics, but it appears that he paid a great deal of attention to discussion of the PMC on the radical Left, and the understanding informed a cycle of three works: Aerospace Folktales (1973); School is a Factory (1979–82) and the long essay “Photography Between Labour and Capital” (1983).7 Arguably, similar issues underpin Untitled Slide Sequence (1972). In this essay, I concentrate on Aerospace Folktales and “Photography Between Labour and Capital.”8 The former pre-dates the Ehrenreichs’ essays, but it shares central themes with their analysis (his final version was revised six years after their essays appeared). In any case, my claim is not that Sekula repeated or simply illustrated these arguments, but that his work, in and on photography, elaborates an analysis of the PMC in dialogue with other socialists.9 He was thinking about these issues with, and alongside, co-thinkers. Sekula did what he could with his medium of photography, in words and pictures, to track the contradictory ideology of the PMC. Aerospace Folktales examines the values of his father, an unemployed aerospace engineer. As he put it: “I wanted to chase my father’s ideology out into the open” (AF 161). His essay “Photography Between Labour and Capital” scrutinises the “picture-language of industrial capitalism” and the role of engineers in elaborating that language (PBLC 203). As we will see, his engagement is broader than this specific cycle of works, because his highly influential essays, collected in Photography Against the Grain, trace the ideologies of photography to the view from the middle.

Accounting for the middle

There are various sources for the idea of the Professional-Managerial Class, but a nucleus of the argument is found in two articles by Barbara and John Ehrenreich, published in Radical America in 1977 (not 1979 as previously stated on nonsite).10 The first—“The Professional-Managerial Class”—offers a sociological analysis of this intermediate stratum; whereas the second —“The New Left: A Case Study in Professional-Managerial Class Radicalism”—lays out the aporias stemming from the Left’s social base in this layer. Together, the essays address a confluence of questions, some of them hoary: why is there no socialism in the USA? Why are blue-collar workers hostile to socialism? Are industrial workers any longer the central force for change? Does Marx’s two class model—and the associated “immiseration” thesis—fit the contemporary situation?11 How could the New Left move beyond the campus ghetto? Answers to these problems have received a spectrum of answers ranging from attention to racialised divisions within the working class, associated with Theodore Allen, David Roediger and Mike Davis, to the embourgeoisement thesis of Goldthorpe and others.12 The Ehrenreichs offered their own provisional responses to these dilemmas, centering their analysis on the layer of salaried professionals situated between working and capitalist classes. They claim this stratum, which expanded significantly in the twentieth century, had been largely ignored by the Left. Nonetheless, the fate of socialism, according to the Ehrenreichs, was tied up with changes within the PMC, because the group was sinking down the social scale, creating a potentially new anti-capitalist force.13 For the Ehrenreichs this change was not without its contradictions. The fact that socialist groups drew most of their activists from this layer, they claim, often alienated manual workers.14

The Ehrenreichs’ central claim is that “the technical workers, managerial workers, ‘culture’ producers, etc.—must be understood as comprising a distinct class in monopoly capitalist society,” which they define as “the Professional-Managerial Class” (PMC 11). While recognising that class is an analytical category and that classes only fully exist in conflict, they categorise the PMC as “consisting of salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations” (PMC 13). Amongst this group, they list: teachers, social workers, entertainers, psychologists, writers of TV scripts and advertising copy as well as “middle-level administrators and managers, engineers, and other technical workers” (PMC 13–14). According to their definition, anywhere between 20% and 25% of the U.S. population belonged to the PMC in 1977, around 50 million people (PMC 15).15

According to the Ehrenreichs the PMC must be viewed as a distinct class formation, because it is antagonistic towards the other main classes: occupying a supervisory position over the working class, while constantly forced to defend its autonomy from capitalist pressures. This class situation gives rise, they suggested, to a specific ideology, based on the resource of specialist education and training.16 The ideology associated with this class location emphasises autonomy, professionalism, accuracy, rationality, efficiency, standardisation, systematisation, order and objectivity (PMC 22).17 At times, this view of life based on the values of expertise tips over into a technocratic critique of capitalism as irrational and anarchic. One solution sometimes offered to this “irrationality” is the rule of the experts, in evidence from Veblen to the U.S. Socialist Party (PMC 23).18 This element of the analysis—which I’m tempted to call “the spontaneous philosophy of the engineers”—is of particular importance for understanding Sekula’s contribution.19

In their second, companion essay, the Ehrenreichs explore the implications of this sociological analysis for socialists in the U.S. Centrally, they argue that the New Left drew its cadres from the PMC and that their life experience influenced its fate. The 1950s and early 1960s were a “golden era” for the PMC with the expansion of higher education and increased expenditure on science and research, but increasingly the members of this class found themselves compelled to uphold their autonomy and professional status in the face of capitalist imperatives for control. They argue that the anti-war movement challenged the authority of the university on which PMC identity was predicated and the Black Liberation Movement and Third World insurgency propelled “PMC youths to confront the conflict between their class’s supposed values and American social reality” (NL 13). Revulsion against their own class, according to the Ehrenreichs, produced two strategic orientations among radicalised members of the PMC: the first involved a critical perspective in the professions, employing their skills and training to advance a Left agenda; the second was the rise of the New Communist Movement, the mazey tangle of political groupuscules mainly Maoist in inspiration, amounting to, in the estimation of Max Elbaum, perhaps 10,000 activists.20 In their “rejoinder” to the debate of their PMC essays, the Ehrenreichs cite the desire of Maoist groups to purge “petty-bourgeois” ideas from their organisations as one factor that led them to consider the role of this middle layer in socialist politics: “the sheer silliness of these polemics over class had the effect of immunizing many sober people against the recognition that there might indeed be some kinds of ‘class problems’ on the left.”21

Whatever the conceptual problems of the PMC thesis, it does register matters of political significance, with two factors worthy of note. The problem that has repeatedly confronted the Left, according to the Ehrenreichs, is that the working class is as likely to be anti-PMC as anti-capitalist. This hostility has an objective basis in the “humiliation, harassment, frustration, etc.” working people experience at the hands of members of the PMC (NL 19). It was frequently working-class activists who responded most enthusiastically to the Ehrenreichs’ argument, indicating how alienating they found small socialist circles dominated by members of the PMC: “I was terrified at those meetings. Every time I opened my mouth I was afraid I was going to say something dumb.”22 The Ehrenreichs put their finger on a genuine experiential factor that provides a significant impediment to socialist organising then and now.23 Secondly, since the 1970s the idea of the “middle class” has played an important role in the political strategies of both the New Right and the liberal centre. In a rightward moving polity, the “middle-class” became a signifier for different hegemonic strategies, all marked with the fantasies of racialised ethnos. For the New Right this has involved positioning a layer of the liberal PMC as “the establishment” or the “liberal elite” intent on imposing its values and life choices on others.24 When Trump or Johnson claim to be maverick outsiders it ought to be apparent we are witnessing a peculiar hegemonic manoeuvre, involving the mobilisation of fantasy and (often racialised) resentment.25 However, working-class anti-communism is not simply invented by the Right, it has real roots in “a wholesale rejection of anything associated with the PMC—liberalism, intellectualism, etc” (NL 20).26 At the same time, liberal centrists claim the need to win the middle class as a justification for their rightward drift.27 In the liberal recoil from radical politics, the working class—often marked with the profoundly ideological marker “white”—is positioned as the reactionary repository of all forms of bigotry and prejudice. Barbara Ehrenreich calls this image of the working class “a psychic dumping ground,” which sounds correct.28

The Ehrenreichs stake their claim for treating the PMC as a distinct class on a shared experience of education and salaried status as “mental” workers involved in the reproduction of capitalism. There are technical questions of class analysis at stake here, explored by Erik Olin Wright and others, but one fundamental issue stands out: to what extent do artists (and other cultural workers) and engineers (and related technical professionals) occupy the same position in the relations of production?29 Like the theorists of the “new working class,” the Ehrenreichs overly homogenised the PMC, eliding key differences.30 The question of the coherence of the PMC is not just a matter of intellectual nit-picking or sociological refinement. Engineers, research scientists and technical professionals play a direct role in the capitalist enterprise and accumulation process in a way that artists simply do not (the fevered imagination of some cultural theorists notwithstanding). Wright observed this ambivalence, but it was David Noble who advanced a trenchant critique of the PMC thesis in these terms.31 Noble insisted that, teachers aside, engineers and associated technical professionals make up the largest single modern profession. This is an important line of demarcation, because this significant group, he argues, stand with capital, noting that on average specialist engineering employees spend only ten years (often less) in technical work before advancing into management roles.32 The management of (recalcitrant) labour—the “man problem”—is as central to their activity as manipulating technological systems.33 Technical employees do not fit the Ehrenreichs’ conception of the PMC as a class involved in the reproduction of capital, because engineering professionals play a role at the heart of the accumulation process, their work is productive as well as reproductive.34 Engineers are involved in a range of activities in the workplace, whether designing apparatus, developing pay schemes, orchestrating work patterns or eliminating “waste,” but all are aimed at “efficiency,” “rationalisation,” and maximising profitability.35 The Ehrenreichs recognised that as much as 70% of science is currently conducted in private business and that the division between the academy/industry is overdrawn, but they continued to ignore this line of demarcation in the middle layer (PMC 28). Too much of the current debate follows their example. It is telling that the Ehrenreichs do not consider the importance of the military-industrial complex in shaping the ideological perspective and political allegiance of this sector of the PMC and binding them to state-capital through the permanent arms economy. As Noble noted in another study, by 1964 the aerospace industry had become the largest sector of American manufacturing and 90% of research funding came from the government, particularly the Air Force.36 As we will see, Sekula was taking notes.

This division between technical personnel, members of the “liberal” professions, and low-grade white-collar workers makes it difficult to identify a coherent PMC bloc with a consistent ideology. Like all ideologies, these systems of belief can be internally contradictory—with values of professionalism and expertise creating a distance from the working-class below them, but at other times inducing resistance to capitalist control. Nevertheless, while both perspectives partake of this tension, in very broad-brush fashion, we can say that the ideology of the engineers tends to “objectivity” and fantasies of rational control, while the arts professionals incline to radical individualism and romantic anti-capitalism, which sometimes takes elitist forms. This division seems even more significant than that between those employed in the private and state sectors and certainly makes it difficult to envisage a class that might be won to alliance with the worker’s movement.37

Some members of the PMC—teachers, many clerical workers and precarious arts practitioners—face social decline, resulting from what Al Szymanski called the “surplus of college graduates” that developed during the 1970s, leading to “considerable downward pressure on the salaries of the new petty bourgeoisie.”38 This motion propels some members of the PMC into the upper layers of the working class and this may lead them to consider alignment with Left perspectives. However, even in decline the PMC can remain fiercely attached to ideologies of autonomy and professionalism and view the precipitous decent into the working class as a form of social death. As André Gorz put it: “the rebellion of intellectual workers is profoundly ambiguous: they rebel not as proletarians, but against being treated as proletarians.”39 This is especially true for engineering and associated professionals who, whatever real pressures on their autonomy, align themselves with the interests of the capitalist class. Stanley Aronowitz notes that the Ehrenhreichs are correct to say that these technical professionals occupy an antagonistic position towards the working class, “but they are not antagonistic in the last instance to capital.”40 One possible answer to the Ehrenreichs’ question as to why the PMC was unable to consolidate a broad anti-capitalist bloc might be to observe that its different elements pull in distinct directions: some towards increased state spending and social reforms, others to technocratic allegiance with the industrial/military complex.

The view from the middle

So far we have seen that despite some important insights, there are serious contradictions in the PMC thesis. Sekula navigated them by homing in on the wing of the PMC that plays a technical role in manufacture, exploring the ideology of an unemployed engineer in Aerospace Folktales and the technical imagination in “Photography Between Labour and Capital.” In what follows I present these works heuristically in reverse order; this is because “Photography Between Labour and Capital” explicitly articulates concepts that help understand the issues at stake in the earlier work.

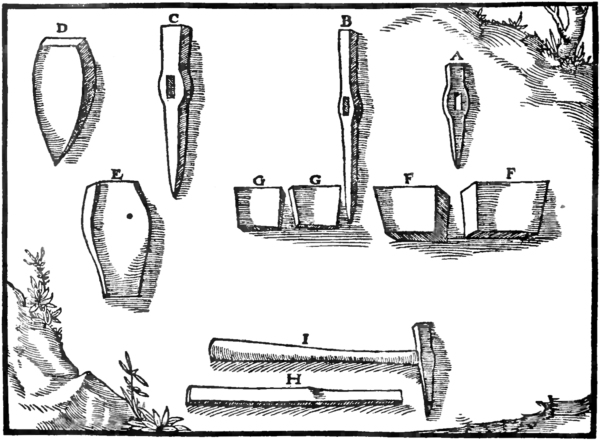

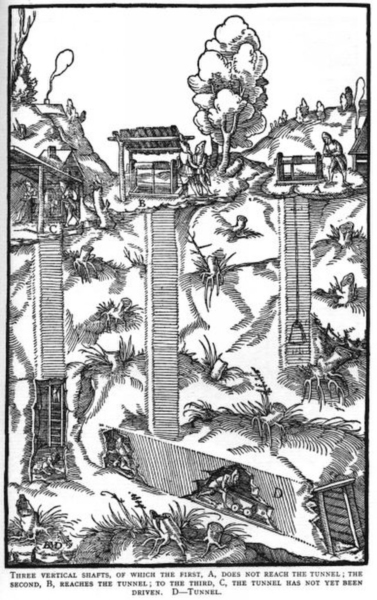

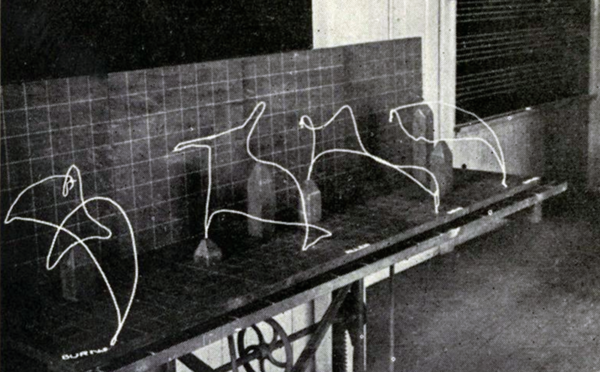

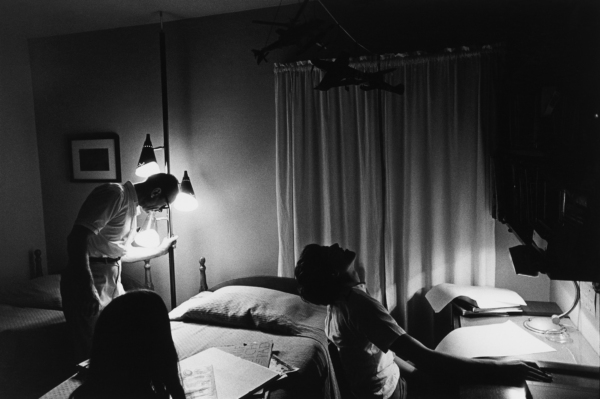

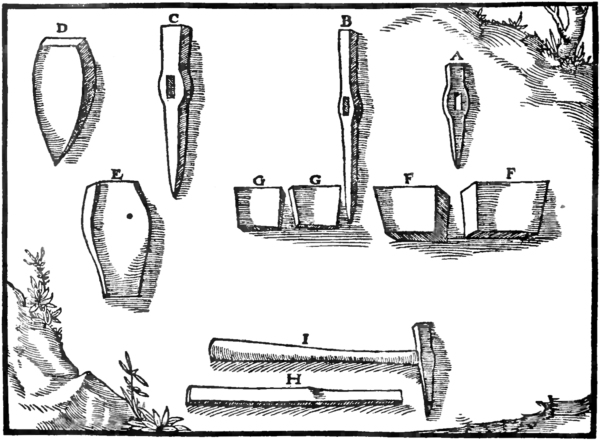

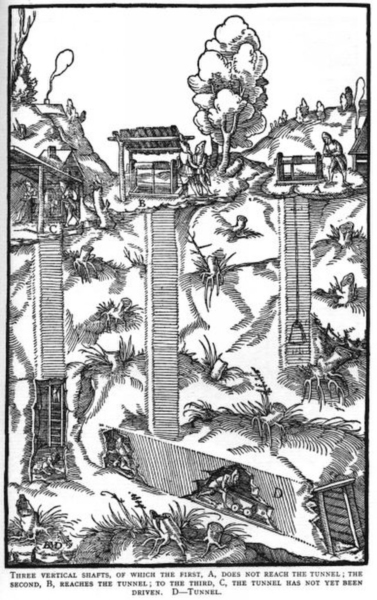

Sekula’s major essay “Photography Between Labour and Capital” stems from an engagement with the archive of the commercial photographer Leslie Shedden, who worked for two decades (1948–68) in a Canadian mining town, producing portraits for miners and images for the company’s public relations arm. Sekula’s investigation of Shedden’s archive opens onto a consideration of the antinomies of photographic culture: historical document and aesthetic picture; empiricism and romanticism; “optical truth” and “visual pleasure,” which he characterises in this study as the opposition between “the instrumental realism of the industrial photograph and the sentimental realism of the family photograph” (PBLC 201). In addition, the subsumption of manual to mental labour is the core theme in the second part of the essay, entitled “The Emerging Picture-Language of Industrial Capitalism.” The 1970s saw an international debate on the labour process as socialist intellectuals rediscovered this element of Marx’s thought, and Sekula’s analysis involves thinking labour process analysis as pictorial form.41 This important second section focuses on the part “played by scientific picture-making in the historical development of capitalism, in the construction of capitalist dominion over nature and human labour” (PBLC 203). Starting from Georgius Agricola’s sixteenth-century mining treatise De Re Metallica (fig. 1 and fig. 2), he examines the plates of the Encyclopedia (fig. 3), Poe and Arago, Wendall Holmes’s “global library of exchangeable images” that were “engraved for the great Bank of Nature” (PBLC 219), along with English Utilitarianism, Nadar’s fetishistic images made in the sewers and catacombs of Paris and Timothy O’Sullivan’s “technical sublime” in the age of the Molly Maguires. The essay culminates with the Taylorist time-and-motion studies of Frank B. and Lillian M. Gilbreth (fig. 4). Sekula employs this history to recast the prehistory of photography, which, he said, is to be found in practices of “technical realism,” “functional realism” or “instrumental realism” (PBLC 203; 234; 201; 215).42 “Photography Between Labour and Capital” is a study in the spontaneous ideology of the engineers.

Despite differences between the three phases in the development of capital’s picture language—Agricola’s De Re Metallica (1556), the plates of the L’Encyclopédie (1751–72), and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth’s time-and-motion studies using photography and film—in each instance we see the elaboration of a “view from nowhere.” This is a disembodied, displaced vision that lays claim to objectivity and neutrality, because it appears to be above social interests. Historians of science have written important studies that trace the emergence of the modern idea of “objectivity,” which they distinguish from truth claims. They see objectivity as involving subtraction of the observer’s subjective experience: “men of science” saw the observer as liable to error and partiality; attention might flag and their senses were deemed unreliable. Imaginatively displacing the self from the scene of observation also helped mediate conflicts and disagreements between gentlemen. Repeatable experiment and technical apparatus, cameras included, played an important role in this moralising of the self, through restraint and self-control.43 The objective observer was imagined to be impersonal, almost automatic. It is rarely mentioned, but the objectivist ideology of the engineers mechanises them as much as it does workers, who, at least, remain organic “hands.”

One problem with this account is that, as a depoliticised version of Foucault, it gives insufficient weight to how these claims to objectivity and neutrality helped secure the authority of experts as middle-class subjects.44 Similarly, the “assertion of neutrality” through which photography renders itself “transparent” enables both technical specialists and media professionals to disavow “tendentious rhetoric.”45 In tying disembodied vision to labour process analysis, drawn from Harry Braverman, Roland Barthes, Alfred Sohn-Rethel and others, Sekula demonstrates that technical realism plays a significant role in the subsumption of labour power.46 For instance, he notes that in his essay “The Plates of the Encyclopedia” Barthes offers an excellent semiology of instrumental realism, but he is entirely silent on the structuring division of mental and manual labour that the images embody. Ostensibly involving an alliance of intellectual and manual labour, according to Sekula, the plates rested on “a hidden hierarchy,” where “the intellectual was the active agent” and the labourer the object of scrutiny (PBLC 213–14). This technical vision is a view from the middle and the middle-view is a powerful location, perhaps a vanishing mediator, which secures a place for technical experts in the division of labour as independent and neutral arbitrators between the forces of labour and capital. Their spontaneous ideology emerges from this position of authority within the production process.

The work of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth plays a core role in Sekula’s analysis as the most visual component of scientific management. These disciples of Taylor employed the photographic technology developed for recording motion by Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge and applied them to itemizing and detailing the gestus of labour. Using lights and an “automicromotion” device, “the worker’s own capabilities” could be represented in photographs as abstract actions, to be dissected, reconstructed and subordinated to managerial control and the regime of capitalist time (PBLC 247).47 Sekula calls the result an “analytic geometry of work” (PBLC 246). Lillian Gilbreth also sought to extend this form of rationalising labour to the home and her work is one place where sentimental and instrumental realism are synthesised, so that the picture-language “speaks with three overlapping voices: the voice of surveillance, the voice of advertising, and the voice of family photography” (PBLC 248–49). As an aside, it is worth noting that Sekula follows Braverman in seeing Taylorism as the central logic of modern industry and there is a big debate here, because Braverman tends to present Taylor as the ventriloquist’s dummy for monopoly capitalism itself, arguably giving too much importance to this management trend.48 This over-estimation of Taylorism is woven into the tradition of Critical Theory, through Lukács and the Frankfurt School to Marcuse, for whom a “technological veil” lies at the heart of capitalist domination.49

Braverman picks up this tradition, but as Bill Schwarz observes, he does so partially, because consideration of the separation of mental and manual labour—conception and execution—precedes the discussion of technology in Labor and Monopoly Capital.50 Contemporary labour process theory sees the mechanisation of work as an instance of the fundamental division between, on the one hand, conception and control, and on the other, execution. While Sekula may have over-inflated the significance of Taylorism in capitalist domination, his focus on the spontaneous ideology of the engineers allows him to foreground the central issues of control and objectivity; Taylorism is merely one particularly naked example of this ideology. Sekula’s emphasis on abstraction similarly helps him avoid reduction of the labour process to technological domination. Across the seemingly diverse aspects of the representation of labour examined, he identifies a common thread involving capitalist processes of “abstraction.” As he puts it, when discussing the work of the Gilbreths: “These images presented the worker’s own capabilities as a ‘thing apart,’ and as an abstraction” (PBLC 247). Following Sohn-Rethel, abstraction is not simply contrasted with the concrete or particular (“false immediacies”); rather, “bad abstractions” are distinguished from the “real abstractions” generated by the commodity-form.51 For Marx, “real abstraction” is not mere illusion; it is, as Alberto Toscano puts it, a “social, historical and ‘transindividual’ phenomenon” rooted in actual processes of capital accumulation.52 It is the point at which capital mysteriously “appears,” as an “automatic subject”; capital “personified”; and as a “self-moving substance.”53 In Sekula’s account of photography, abstractions—in the form of equivalence, fragmentation, calculability, inter-changeability, measurability, detachment, and rationalisation—preside over the activity of observing and transforming the labour process.

In the capitalist division of labour, the control of the total labour process passes from skilled artisan to capitalist or overseer, separating conception from execution, and the proletarian is reduced to a mere “detail worker,” consigned to a particular, repetitive and fragmentary labour task. Mechanization is one way of achieving this, but it is not the only one. Sekula finds the same process in the photographic archive and The Family of Man where photographers figure as comparable detail workers, responsible for producing small lexical units within a larger ensemble, “providing fragmentary images for an apparatus beyond his or her control” (PBLC 194, 251).54 In this process, the mathematicisation of picture-making, he suggests, contributed to the “rationalisation” of work (PBLC 205–06). We find its logic in modern HR departments and their endless personnel files, satisfaction surveys, job specifications and recruitment procedures. In this way, this production of subjects is modelled on the commodity-form, perhaps more so than it ever was in factories.

“Photography Between Labour and Capital” provides an in-depth analysis of one component of photographic ideology, associated with technical realism and objectivity. It focuses on the realism of the engineers, but it points to a tension structuring photographic ideology more broadly, between historical document and aesthetic picture, empiricism and romanticism, instrumental realism and sentimental realism. The essays collected in Photography Against the Grain attend to these issues in a wider frame, considering the transformations and contradictions in the discourse of photography. As he put it in the essay “The Traffic in Photographs,” “photography is haunted by two chattering ghosts: that of bourgeois science and that of bourgeois art.”55 From 1839 onwards defenders of photography have oscillated between these positions. In unpacking the careening of “the hermeneutic pendulum” between these antimonies, Sekula unravels both claims to neutrality and objectivity and the equal and opposite view that believes that the subjectivisation of the machine might humanise technology.56 Sekula’s singular intervention is to have understood that ideas about photography cannot be separated from attitudes to technology, the division of labour and the subsumption of skill. Photographic history is an unacknowledged commentary on the capitalist labour process, and photography, in its incoherence, exposes a fault line in thought. Sekula doesn’t ever put it like this, but his account of the antimonies of photographic ideology—objectivism and affect—points to the dirempt wings of the PMC and the overlapping debate on capitalist labour processes. His account of photography is built from an understanding of the unstable configuration of the middle, caught in two sets of contradictions between capital and the working class, but also between the spontaneous philosophy of the engineers (technical realism) and the romantic anti-capitalism of the cultural intelligentsia (subjective affect). His understanding of capitalist image-culture owes a great deal to the debate during the 1970s on the PMC.

Close to home: Aerospace Folktales

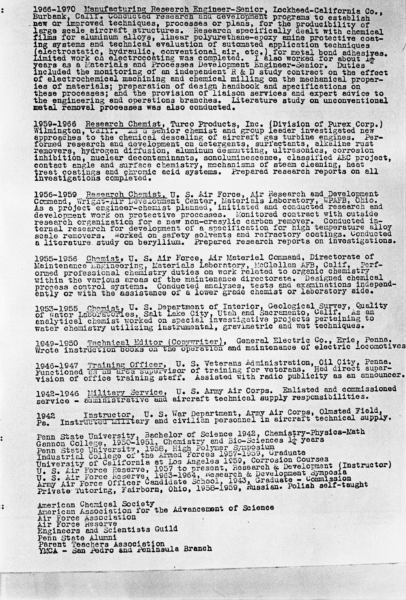

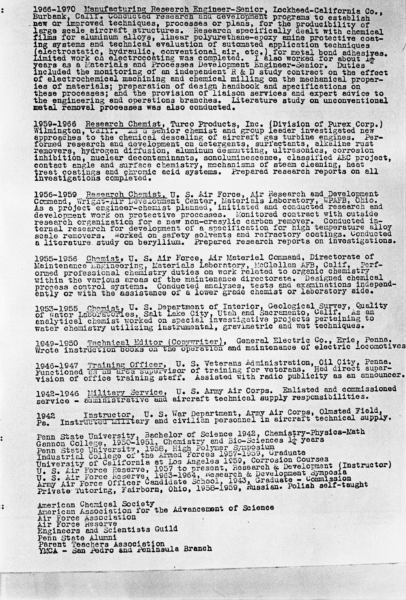

Aerospace Folktales was Sekula’s first look at the PMC. I come to it last, because it offers a vantage point for seeing the spontaneous ideology of the engineers under crisis conditions, but also because the ideas elaborated in “Photography Between Labour and Capital” help illuminate the issues at stake. The figure of the “engineer,” who is at the heart of this work, picks up many of the ideological terms we have encountered: “A good scientist and engineer, with his organizing ability, his preciseness, his ability to adapt to different situations, can be of great value in administrative positions and clerical tasks” (AF 153). Aerospace Folktales is a highly elaborated and formed photo-text work. By the time it appeared in Photography Against the Grain in 1984, it had been honed to fifty-one black-and-white prints, two interviews and a commentary.57 Five photographs appear as intertitles with white text on a black ground. Two images are re-photographed from a corporate relations magazine; two more present written documents, the tenancy agreement for the family’s apartment and his father’s C.V.; three are page spreads from a book on the impact of nuclear weapons; one appears to be a pinboard with medical notes (two names are redacted), we see it again more fully in a picture of the kitchen, with the “wife” making dinner; and one depicts a page from a photo-album with five photographs of the family, two of them apparently portraits of the young Sekula. The remaining thirty-five images could be described as photographs in the “documentary” mode, some are casual, others more formally composed, including posed portraits and details from the apartment.

The work represents the lives of a former Lockheed aerospace chemical engineer, who is now unemployed (the artist’s father), the engineer’s wife (the artist’s mother) and their children (Sekula’s siblings). Lockheed was the biggest employer in the San Fernando Valley in the 1970s and was heavily dependent on defence contracts, but as Benjamin Young tells us, it “was on the rocks for failed commercial airliner ventures; political controversy due to cost overruns, overbilling, and underperformance in its military contracts; [and] a contentious government bailout to prevent its bankruptcy.”58 The negative character of labour, deindustrialisation, precarity and unemployment are here positioned as central features of capitalism and not marginal exceptions. Sekula frames this process socially, as part of the post-war structural crisis of the PMC, or those the father calls “technical-professional personnel” (AF 152). Sekula tells us that “getting laid off is no big deal”; machinists, pizza cooks and secretaries are regularly jobless without it affecting their sense of self, “but this was the first-time experts were getting laid off” (AF 160). Aerospace Folktales gives us some idea of how “technical-professional personnel” experience crisis, and in the process it exposes important aspects of PMC ideology.

Sekula wrote in 1973: “I use ‘autobiographical’ material, but assume a certain fictional and sociological distance in order to achieve a degree of typicality.”59 The reference to “typicality” gestures towards Georg Lukács’s account of realism, but the comment reminds us to retain a distance between the artist’s father or mother and the “father” or “wife.” The “engineer” and the others should be viewed as characters in a photo-play. Portraits proliferate through the work, both portraits of characters and pictures of portraits. Young describes the work as a pendant portrait of the engineer and the wife and this is a valuable insight that highlights distinct gendered worlds, even if it is complicated by the presence of the siblings.60 However, this characterisation elides the central role played by a third character who has gone unnoticed in commentaries, the one called “I” who comments on the others. Aerospace Folktales cannot be understood without taking into account this third persona. In what follows the father/engineer, mother/wife, the siblings and the I should all be imagined as if in quotation marks.

Sekula’s well-known comment about creating a photo-work in the mode of “a disassembled movie” comes from his “Introductory Note” to Aerospace Folktales (AF 106). In some regards, the work parallels This Ain’t China, but here the insertions, disruptions and narrative reframing attain, if not coherence—given the Brechtian ambition of the work that cannot really be expected—then a narrative drift. This plot has gone unobserved, but it is significant, recording a shift from the public (male) world of engineering to the private, domestic interior. Aerospace Folktales documents the crisis in social relations of the American industrial-military complex as they enter the domestic sphere, but it also adopts a mode of presentation that foregrounds its fictionalised or performative character (in this sense it is a work against “absorption”). It is worth hanging on to the reference to “folktales.” We know that Sekula read Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale, perhaps the most rigorous of Formalist studies. The signs of this staging are evident throughout, with the characters acting out roles for the camera. Photographing indoors in small domestic rooms means that participants are always aware of the camera’s presence—in a time of mass media even the private realm involves striking poses. In one image we see the father handling the plate camera. Sekula’s “Commentary” with its repudiation of syntax amplifies this fragmentary, stagey character. Interpretations of Aerospace Folktales must navigate the tension between its fictive dimensions and its realism, but that is a contradiction in some prevalent theoretical models, and not in realist art.

A sequence or storyline can be described. The first grouping of three photographs consists of a text quoting the Lockheed chairman, taken from Days of Trial and Triumph: A Pictorial History of Lockheed, published in 1969, and two grainy images from the Lockheed Star, the bi-weekly newsletter of the corporation, also from 1969. (In The Salaried Masses, Kracauer cites “sceptical employees” who referred to an equivalent publication, rather wonderfully, as “The Slime Trumpet.”)61 All three are probably re-photographed and he may have found them in these company publications in the engineer’s home. In the first image in the sequence (the second frame) (fig. 5), a mixed group of men converse in front of a helicopter: three are older men in business suits, two wear military officer’s uniforms, a pilot appears behind them. In the next (fig. 6), we are presented with a larger group, most in shirtsleeves, giving a “thumbs up.” As informal as this image is, most of the participants wear ties and they are probably managers or technical workers. Perhaps it is a corporate portrait of a PMC workgroup. From the outset, the scene is set in the military-industrial complex. This opening sequence represents the official, celebratory perspective of the company and it is the first indication of Sekula’s interest in company photographic archives, which he would develop in “Photography Between Labour and Capital.” Given the overall focus on the engineer’s unemployed situation, this triumphalism appears hollow; it is cast in ironic mode. In this sense, Aerospace Folktales could be described as a study in ideological deflation, a story about “people who have internalized a view of themselves as ‘professionals’ and subsequently suffer the shock of being dumped into the reserve army of labor.”62 This abiding illusion in professional independence is a key blockage on the radical political potential of the PMC considered by the Ehrenreichs and highlighting this obstacle to class self-understanding is an important component of this phase of Sekula’s realist art.

This initial cluster of three frames is followed by another triadic sequence, which opens with a depiction of the father and his friend in the empty parking lot of the Lockheed aerospace plant where he had been employed (fig. 7). Now labour appears in double negative: the engineer is described as unemployed and his friend is dressed for leisure in shorts and a casual, printed shirt, either he is on holiday or, more probably, he has retired from employment. Both men are positioned on the outside of the labour market. They embody two versions of this state of idleness: as (utopian and, perhaps, pastoral) leisure and as (tragic) insecurity. The second photograph is a detail from the plant building, seen from below, from the position of pedestrian or driver, and the third is a close-up of the father at the wheel of his car. Sekula’s work often employs this filmic expansion and contraction of framing. Here a metonymic connection is established between industrial complex and a particular subject. The next three pictures present the engineer, his wife and one sister outside their apartment, the girl plays with a ball; a more tightly framed portrait of the parents against the garage door (they were made on separate occasions); and the façade of the building. The narrative then shifts indoors, where all the remaining photographs were made.

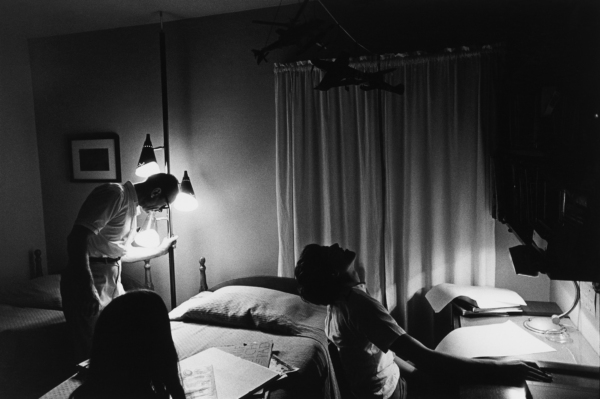

Aerospace Folktales treats the precarious class location of the PMC or the “petty bourgeoise,” to use Sekula’s formulation. Class is a leitmotif of realism, but few artists address their own class position, so attention to “social material” here involves turning inward; a focus on the self, rather than a downwardly directed gaze on those lower on the social scale.63 Commentators have noted the theme of unemployment and loss of position, but the point might be amplified and the move into the interior can be seen as a form of de-masculinisation. As the engineer’s wife observes, there is a prevailing attitude that “if a man is out of work there is something wrong with him” (AF 156). In A Short Autobiography, which was a first try out for elements of this work, Sekula refers to his father as “unemployed” and his mother as “employed,” adding that they are both “dressed for work,” him for posting resumes, her for domestic labour. This reversal is important, because Aerospace Folktales is one of the first works to make social reproduction and the “unpaid labour” of housework a central theme (fig. 8). The “wife” herself claims she has never worked, but her invisible labour is made apparent; the dinner table with place settings for six and kitchen as setting for a labour process feature prominently (AF 158).64 There are ways in which worlds collide here, because the mise-en-scène of the mother’s work is shaped by the products of the engineer’s world; his world folds in on hers. As Ruth Schwartz Cowan reminds us, post-war domestic labour was transformed, without being reduced, by a range of electrical commodities: the images of the kitchen include a prominent General Electric refrigerator and an electric mixer, toaster and kettle.65 Elsewhere, a radio is in evidence. This is the domestic sphere moulded by mass-produced commodities. The father’s nightly process of fussily rearranging lamps appears, in this light, as a symptom of precision displaced from industry to the domestic space (fig. 9).

Aerospace Folktales involves a series of reflections on the habitus of the PMC, the typical gestures, speech patterns, behaviour and values associated with this group. Sekula uses a different term in his commentary: he calls it their “art”— “lower-level technocrat art”—meaning something like their way of representing themselves to themselves and to others (AF 160). The term allows him to make a connection with his own activity as an artist and his (growing) distance from them. The distance is significant, and Aerospace Folktales is shaped by, perhaps built on, this Buddenbrooks moment—a fault line within the PMC, whether marked along the generational axis or the cultural/technical one, or both. Even in the opening image at Lockheed depicting the engineer and his friend, the intertitle informs us: “Unable to fathom my motives, they were uneasy.” The use of the generic third person calls attention to the first-person narrator. Enunciative features are present throughout. It is worth noting that the first intertitle includes “I” and the concluding photograph incorporates portraits of Sekula. The work also includes his reflexive commentary. It is framed, or bracketed, through his extra-diegetic perspective on their world and its values.

Aerospace Folktales draws the habitus, or art, of the technical PMC into the light. He mentions his mother—“the wife”—in his Commentary, but the focus really falls on the “father”: “I wanted to chase my father’s ideology out into the open.” In this sense, the Commentary is lopsided, more so than the image sequence. The title, opening sequence and specific details, such as the C.V. and manual on nuclear blasts, the décor that we are told is largely the engineer’s creation, these elements make Aerospace Folktales primarily the engineer’s story (fig. 10). The wife appears in significant ways in the photo sequence, but her interview is also primarily about her husband and the effect on him of losing his position. The central theme of Aerospace Folktales is the impact of unemployment on a PMC family, and on the way that it disturbs, or otherwise reverberates, in the perception of a technical professional, invested in capitalist industry. Order is a significant sign in his world: “everything had its place… everything had its order… I mean it was his [the engineer’s] only defence” (AF 163). Regularity and routine are presented as the armour of a man “caught in the middle,” surrounded in the apartment complex by those lower in the social scale and afraid of slipping down among them: “cops pipefitters old people army sergeants divorcees with kids….” At one point in the commentary, Sekula observes: “my father built a middle class submarine because he was sailing in a blue-collar ocean and he didn’t want the sharks to eat his kids” (AF 162; 163).66 Perhaps more than the watery metaphors, it is the sign “middle” that matters. The engineer works to sustain a system of belief in which his unemployment is “a dysfunction of a perfectly equitable system” (AF 161). In his interview, the engineer sees waste of expertise, inadequate understanding, and technical solutions for redeployment, but not systemic crisis. To imagine unemployment in any other way might cause him to revise his hierarchy of values. It would call into question such middling ideas as merit, intelligence, opportunity and hard work. It might even challenge the base line of PMC ideology, the belief in “unique individual talent” (AF 162). When the father does speak about his situation he sounds like “fortune magazine” or the “lockheed chairman of the board” (AF 163). On complaining of government waste of tax dollars on foreign aid, Sekula asks him about aid to the South Vietnamese, but he declines to criticize and can only point to “mismanagement,” identifying more with the aerospace industry as a direct beneficiary of the Cold War (Russia abroad, labour at home) than with his own needs, and retains his belief in individual merit (AF 152–53).67 All the ordered details of commodified living evident in the photographs appear as defensive ramparts against recognition of the “real conditions of existence.” Sekula presents the image of the engineer’s resume as a condensation of this art: “a capsule description in writing of what your experience has been” (AF 152). In the process, he stages the qualified identification of a technical worker with the system, even in conditions of crisis.

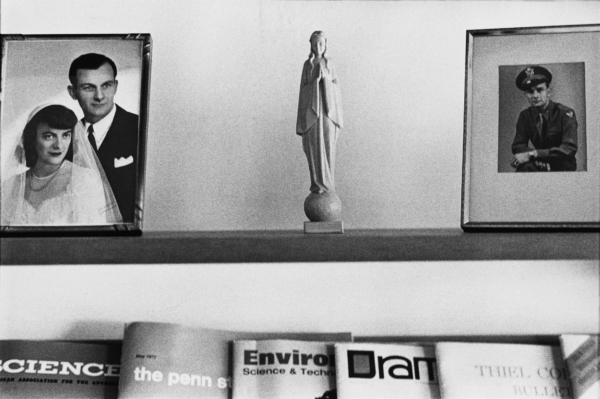

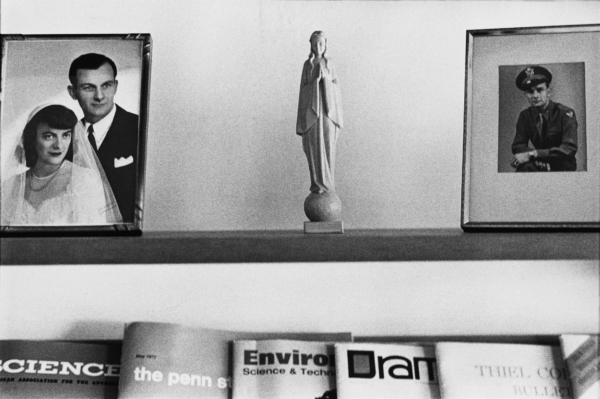

Many of the images in the sequence offer details of this habitus: neat, clean spaces with everything in its correct place; classics of literature in hardback editions, embossed with gilt lettering carefully lined up; the armchair still wrapped in plastic to prevent it soiling; a crucifix; and the science magazines arranged in a neat row, above them a figurine with hands clasped in prayer and two studio portraits, the couple’s wedding portrait and a picture of his father in Air Force uniform (fig. 11).68 Similarly, the typewriter, positioned on a side table in an alcove, on which his father writes job applications with flowers next to the radio, are presented as still life’s.69 The photographs of these arrangements are designed for comparison, calling to mind Walker Evans’s pictures of Depression-era interiors of sharecroppers, such as Washroom and Dining Area of Floyd Burroughs’ Home (1936). This is class figured through the “phantasmagoria of the interior” in the mode of Atget’s folio Intérieurs Parisiens.70 The model planes and helicopter, assembled from kits and suspended from the ceiling, are particularly telling details. One is photographed from an oblique angle—ensuring we take in the crucifix on the wall behind. The other is made from a low point-of-view, positioning the beholder underneath the U.S. Army helicopter, as if we are menaced by its destructive power, one the engineer has helped create. The Church and the Air Force pervade this environment. Then there is the small pamphlet The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, pulled from the bookcase and opened up by Sekula. Three separate page spreads for the booklet are displayed: five photographs show the effects of thermal radiation on bodies and objects and two diagrams model the impact of the blast. All are intended to be typical details, symptoms if you will, for an “art” of the PMC that is imbued with an ambivalent attitude to the U.S. military-industrial complex: one where strong identification is at odds with a sense of neglect of his individual talent. Sekula adds into this mix details that reveal the violence and destruction ensuing from the professional investments.

Aerospace Folktales is, in many ways, a negative work. In contrast to the positive image of the labouring body more typical in realist art, it focuses on forms of unwaged existence—leisure, domestic work and unemployment. The layerings of semi-fiction and autobiography in images, text and oral presentation register the shocks of capitalist crisis in ideology and track that effect at the level of the family microcosm. It should be borne in mind that this is a project concerned with class location that includes the artist. Sekula’s work is never straightforwardly autobiographical, conscious that personal experience is always mediated by wider structural relations and requires the labour of form giving. What emerges is not directly lived incidents, but a shaped and moulded representation, that turns the lens on the PMC (including the “I”), exposing the invisible middle to scrutiny. The subject who makes representations, including the artist, is not an objective observer above social interest, able to survey other lives with imperious calm and detachment, but a subject with a class location and the investments (psychic and social) that entails. Aerospace Folktales is a study of the PMC from the inside out and is formed from the tension between the crisis, which, according to the Ehrenreichs, Sekula’s generation of lower-middle class professionals were experiencing. The work is riven by the fault line in the PMC that is both generational and entails a clash between the ideology of technical expertise for capital and the critical anti-capitalism emerging among art workers.

There are obvious ways in which Aerospace Folktales relates to the anti-war activism in San Diego, itself an important centre of the U.S. military-industrial complex. The point that can be added, when compared to other artworks focused on this activism, is that it switches perspectives, attempting a view from the interior, to explore with some sympathy the contradictions of those who work in that complex. In oblique ways, the military-industrial complex runs through much of Sekula’s work: Untitled Slide Sequence, “Steichen at War,” War Without Bodies, Fish Story, Lottery of the Sea, The Forgotten Space and Short Film for Laos all retain contiguous relationships to his experience as the son of an (unemployed) aerospace engineer in San Pedro. Aerospace Folktales is a study in transference and counter-transference, conducted from within the PMC: this is not just an external critique of militarism, but one produced by someone who understands that he is moulded by that culture and can never entirely escape it.

Aerospace Folktales, “Photography Between Labour and Capital,” and Sekula’s related studies of photographic ideology are rich and over-determined works. Multiple threads are woven in these projects, but it is important to observe that one of the determinations in play is the debate on the PMC and its implications for socialist organising—what might constitute the social base for a New Left—that emerged out of the New American Movement and which reverberated through the wider networks of the U.S. Marxist Left during the 1970s. Returning to those debates now not only illuminates Sekula’s works of that time, it also highlights some problems of analysis and strategy for socialists today.

Notes

It often appears that academics and associated cultural workers take a critical view of everything except their own place in the world. We hear a great deal about museums “incorporating” critique, but nothing absorbs opposition like the Ph.D. machine, where every cultural infraction becomes material for a career. Similarly, historians of art have paid attention to images of labourers and capitalists, but given remarkably little consideration to their own class fraction—the petite bourgeoisie.1 This grouping, called here the Professional-Managerial Class (PMC), is all around us, yet it goes unnoticed; it is a visible-invisible object.2 Things have changed somewhat in recent times with the debate on affective labour and the precarious situation of cultural workers. Blending post-Workerist ideas with the claims of Boltanski and Chiapello in The New Spirit of Capitalism, some art-activists claim that the experience of “flexible” intern labour provides a model for the subjectivised or affective character of modern work.3 This focus on precarious labour, particularly union organising among low-paid and casualised workers, is to be welcomed, but if the class location of artists, academics and curators was formerly a blind spot, it is now inflated into the grounding condition of the contemporary economy and it is the social structure of capitalism, rather than the position of academics, that becomes invisible. The approach of cultural intellectuals to their own class position seems to be all or nothing.

My consideration of the Professional-Managerial Class will be historical in character, but in returning to the 1970s and looking again at the vivid debate from that time on the PMC I aim to highlight aspects of the analysis that have been overlooked in the recent rediscovery of the concept by the U.S. Left.4 Principally, this entails drawing attention to a structuring contradiction within the PMC bloc. The ideas arising from that period discussion might be usefully employed to examine the work of a range of artists, but Allan Sekula stands out as an artist-intellectual directly engaged with this question. In the mid-1970s, like Barbara and John Ehrenreich, who sparked the initial interest in the PMC, Sekula was a member of the New American Movement, a multi-tendency revolutionary-socialist organisation.5 His personal library includes the issues of Radical America containing the essays by the Ehrenreichs, which gave impetus to this line of analysis and, while this does not prove that he paid any particular attention to these texts, other books in his possession show he studied the issues they raised.6

Sekula was exceptionally well read across a wide range of topics, but it appears that he paid a great deal of attention to discussion of the PMC on the radical Left, and the understanding informed a cycle of three works: Aerospace Folktales (1973); School is a Factory (1979–82) and the long essay “Photography Between Labour and Capital” (1983).7 Arguably, similar issues underpin Untitled Slide Sequence (1972). In this essay, I concentrate on Aerospace Folktales and “Photography Between Labour and Capital.”8 The former pre-dates the Ehrenreichs’ essays, but it shares central themes with their analysis (his final version was revised six years after their essays appeared). In any case, my claim is not that Sekula repeated or simply illustrated these arguments, but that his work, in and on photography, elaborates an analysis of the PMC in dialogue with other socialists.9 He was thinking about these issues with, and alongside, co-thinkers. Sekula did what he could with his medium of photography, in words and pictures, to track the contradictory ideology of the PMC. Aerospace Folktales examines the values of his father, an unemployed aerospace engineer. As he put it: “I wanted to chase my father’s ideology out into the open” (AF 161). His essay “Photography Between Labour and Capital” scrutinises the “picture-language of industrial capitalism” and the role of engineers in elaborating that language (PBLC 203). As we will see, his engagement is broader than this specific cycle of works, because his highly influential essays, collected in Photography Against the Grain, trace the ideologies of photography to the view from the middle.

Accounting for the middle

There are various sources for the idea of the Professional-Managerial Class, but a nucleus of the argument is found in two articles by Barbara and John Ehrenreich, published in Radical America in 1977 (not 1979 as previously stated on nonsite).10 The first—“The Professional-Managerial Class”—offers a sociological analysis of this intermediate stratum; whereas the second —“The New Left: A Case Study in Professional-Managerial Class Radicalism”—lays out the aporias stemming from the Left’s social base in this layer. Together, the essays address a confluence of questions, some of them hoary: why is there no socialism in the USA? Why are blue-collar workers hostile to socialism? Are industrial workers any longer the central force for change? Does Marx’s two class model—and the associated “immiseration” thesis—fit the contemporary situation?11 How could the New Left move beyond the campus ghetto? Answers to these problems have received a spectrum of answers ranging from attention to racialised divisions within the working class, associated with Theodore Allen, David Roediger and Mike Davis, to the embourgeoisement thesis of Goldthorpe and others.12 The Ehrenreichs offered their own provisional responses to these dilemmas, centering their analysis on the layer of salaried professionals situated between working and capitalist classes. They claim this stratum, which expanded significantly in the twentieth century, had been largely ignored by the Left. Nonetheless, the fate of socialism, according to the Ehrenreichs, was tied up with changes within the PMC, because the group was sinking down the social scale, creating a potentially new anti-capitalist force.13 For the Ehrenreichs this change was not without its contradictions. The fact that socialist groups drew most of their activists from this layer, they claim, often alienated manual workers.14

The Ehrenreichs’ central claim is that “the technical workers, managerial workers, ‘culture’ producers, etc.—must be understood as comprising a distinct class in monopoly capitalist society,” which they define as “the Professional-Managerial Class” (PMC 11). While recognising that class is an analytical category and that classes only fully exist in conflict, they categorise the PMC as “consisting of salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations” (PMC 13). Amongst this group, they list: teachers, social workers, entertainers, psychologists, writers of TV scripts and advertising copy as well as “middle-level administrators and managers, engineers, and other technical workers” (PMC 13–14). According to their definition, anywhere between 20% and 25% of the U.S. population belonged to the PMC in 1977, around 50 million people (PMC 15).15

According to the Ehrenreichs the PMC must be viewed as a distinct class formation, because it is antagonistic towards the other main classes: occupying a supervisory position over the working class, while constantly forced to defend its autonomy from capitalist pressures. This class situation gives rise, they suggested, to a specific ideology, based on the resource of specialist education and training.16 The ideology associated with this class location emphasises autonomy, professionalism, accuracy, rationality, efficiency, standardisation, systematisation, order and objectivity (PMC 22).17 At times, this view of life based on the values of expertise tips over into a technocratic critique of capitalism as irrational and anarchic. One solution sometimes offered to this “irrationality” is the rule of the experts, in evidence from Veblen to the U.S. Socialist Party (PMC 23).18 This element of the analysis—which I’m tempted to call “the spontaneous philosophy of the engineers”—is of particular importance for understanding Sekula’s contribution.19

In their second, companion essay, the Ehrenreichs explore the implications of this sociological analysis for socialists in the U.S. Centrally, they argue that the New Left drew its cadres from the PMC and that their life experience influenced its fate. The 1950s and early 1960s were a “golden era” for the PMC with the expansion of higher education and increased expenditure on science and research, but increasingly the members of this class found themselves compelled to uphold their autonomy and professional status in the face of capitalist imperatives for control. They argue that the anti-war movement challenged the authority of the university on which PMC identity was predicated and the Black Liberation Movement and Third World insurgency propelled “PMC youths to confront the conflict between their class’s supposed values and American social reality” (NL 13). Revulsion against their own class, according to the Ehrenreichs, produced two strategic orientations among radicalised members of the PMC: the first involved a critical perspective in the professions, employing their skills and training to advance a Left agenda; the second was the rise of the New Communist Movement, the mazey tangle of political groupuscules mainly Maoist in inspiration, amounting to, in the estimation of Max Elbaum, perhaps 10,000 activists.20 In their “rejoinder” to the debate of their PMC essays, the Ehrenreichs cite the desire of Maoist groups to purge “petty-bourgeois” ideas from their organisations as one factor that led them to consider the role of this middle layer in socialist politics: “the sheer silliness of these polemics over class had the effect of immunizing many sober people against the recognition that there might indeed be some kinds of ‘class problems’ on the left.”21

Whatever the conceptual problems of the PMC thesis, it does register matters of political significance, with two factors worthy of note. The problem that has repeatedly confronted the Left, according to the Ehrenreichs, is that the working class is as likely to be anti-PMC as anti-capitalist. This hostility has an objective basis in the “humiliation, harassment, frustration, etc.” working people experience at the hands of members of the PMC (NL 19). It was frequently working-class activists who responded most enthusiastically to the Ehrenreichs’ argument, indicating how alienating they found small socialist circles dominated by members of the PMC: “I was terrified at those meetings. Every time I opened my mouth I was afraid I was going to say something dumb.”22 The Ehrenreichs put their finger on a genuine experiential factor that provides a significant impediment to socialist organising then and now.23 Secondly, since the 1970s the idea of the “middle class” has played an important role in the political strategies of both the New Right and the liberal centre. In a rightward moving polity, the “middle-class” became a signifier for different hegemonic strategies, all marked with the fantasies of racialised ethnos. For the New Right this has involved positioning a layer of the liberal PMC as “the establishment” or the “liberal elite” intent on imposing its values and life choices on others.24 When Trump or Johnson claim to be maverick outsiders it ought to be apparent we are witnessing a peculiar hegemonic manoeuvre, involving the mobilisation of fantasy and (often racialised) resentment.25 However, working-class anti-communism is not simply invented by the Right, it has real roots in “a wholesale rejection of anything associated with the PMC—liberalism, intellectualism, etc” (NL 20).26 At the same time, liberal centrists claim the need to win the middle class as a justification for their rightward drift.27 In the liberal recoil from radical politics, the working class—often marked with the profoundly ideological marker “white”—is positioned as the reactionary repository of all forms of bigotry and prejudice. Barbara Ehrenreich calls this image of the working class “a psychic dumping ground,” which sounds correct.28

The Ehrenreichs stake their claim for treating the PMC as a distinct class on a shared experience of education and salaried status as “mental” workers involved in the reproduction of capitalism. There are technical questions of class analysis at stake here, explored by Erik Olin Wright and others, but one fundamental issue stands out: to what extent do artists (and other cultural workers) and engineers (and related technical professionals) occupy the same position in the relations of production?29 Like the theorists of the “new working class,” the Ehrenreichs overly homogenised the PMC, eliding key differences.30 The question of the coherence of the PMC is not just a matter of intellectual nit-picking or sociological refinement. Engineers, research scientists and technical professionals play a direct role in the capitalist enterprise and accumulation process in a way that artists simply do not (the fevered imagination of some cultural theorists notwithstanding). Wright observed this ambivalence, but it was David Noble who advanced a trenchant critique of the PMC thesis in these terms.31 Noble insisted that, teachers aside, engineers and associated technical professionals make up the largest single modern profession. This is an important line of demarcation, because this significant group, he argues, stand with capital, noting that on average specialist engineering employees spend only ten years (often less) in technical work before advancing into management roles.32 The management of (recalcitrant) labour—the “man problem”—is as central to their activity as manipulating technological systems.33 Technical employees do not fit the Ehrenreichs’ conception of the PMC as a class involved in the reproduction of capital, because engineering professionals play a role at the heart of the accumulation process, their work is productive as well as reproductive.34 Engineers are involved in a range of activities in the workplace, whether designing apparatus, developing pay schemes, orchestrating work patterns or eliminating “waste,” but all are aimed at “efficiency,” “rationalisation,” and maximising profitability.35 The Ehrenreichs recognised that as much as 70% of science is currently conducted in private business and that the division between the academy/industry is overdrawn, but they continued to ignore this line of demarcation in the middle layer (PMC 28). Too much of the current debate follows their example. It is telling that the Ehrenreichs do not consider the importance of the military-industrial complex in shaping the ideological perspective and political allegiance of this sector of the PMC and binding them to state-capital through the permanent arms economy. As Noble noted in another study, by 1964 the aerospace industry had become the largest sector of American manufacturing and 90% of research funding came from the government, particularly the Air Force.36 As we will see, Sekula was taking notes.

This division between technical personnel, members of the “liberal” professions, and low-grade white-collar workers makes it difficult to identify a coherent PMC bloc with a consistent ideology. Like all ideologies, these systems of belief can be internally contradictory—with values of professionalism and expertise creating a distance from the working-class below them, but at other times inducing resistance to capitalist control. Nevertheless, while both perspectives partake of this tension, in very broad-brush fashion, we can say that the ideology of the engineers tends to “objectivity” and fantasies of rational control, while the arts professionals incline to radical individualism and romantic anti-capitalism, which sometimes takes elitist forms. This division seems even more significant than that between those employed in the private and state sectors and certainly makes it difficult to envisage a class that might be won to alliance with the worker’s movement.37

Some members of the PMC—teachers, many clerical workers and precarious arts practitioners—face social decline, resulting from what Al Szymanski called the “surplus of college graduates” that developed during the 1970s, leading to “considerable downward pressure on the salaries of the new petty bourgeoisie.”38 This motion propels some members of the PMC into the upper layers of the working class and this may lead them to consider alignment with Left perspectives. However, even in decline the PMC can remain fiercely attached to ideologies of autonomy and professionalism and view the precipitous decent into the working class as a form of social death. As André Gorz put it: “the rebellion of intellectual workers is profoundly ambiguous: they rebel not as proletarians, but against being treated as proletarians.”39 This is especially true for engineering and associated professionals who, whatever real pressures on their autonomy, align themselves with the interests of the capitalist class. Stanley Aronowitz notes that the Ehrenhreichs are correct to say that these technical professionals occupy an antagonistic position towards the working class, “but they are not antagonistic in the last instance to capital.”40 One possible answer to the Ehrenreichs’ question as to why the PMC was unable to consolidate a broad anti-capitalist bloc might be to observe that its different elements pull in distinct directions: some towards increased state spending and social reforms, others to technocratic allegiance with the industrial/military complex.

The view from the middle

So far we have seen that despite some important insights, there are serious contradictions in the PMC thesis. Sekula navigated them by homing in on the wing of the PMC that plays a technical role in manufacture, exploring the ideology of an unemployed engineer in Aerospace Folktales and the technical imagination in “Photography Between Labour and Capital.” In what follows I present these works heuristically in reverse order; this is because “Photography Between Labour and Capital” explicitly articulates concepts that help understand the issues at stake in the earlier work.

Sekula’s major essay “Photography Between Labour and Capital” stems from an engagement with the archive of the commercial photographer Leslie Shedden, who worked for two decades (1948–68) in a Canadian mining town, producing portraits for miners and images for the company’s public relations arm. Sekula’s investigation of Shedden’s archive opens onto a consideration of the antinomies of photographic culture: historical document and aesthetic picture; empiricism and romanticism; “optical truth” and “visual pleasure,” which he characterises in this study as the opposition between “the instrumental realism of the industrial photograph and the sentimental realism of the family photograph” (PBLC 201). In addition, the subsumption of manual to mental labour is the core theme in the second part of the essay, entitled “The Emerging Picture-Language of Industrial Capitalism.” The 1970s saw an international debate on the labour process as socialist intellectuals rediscovered this element of Marx’s thought, and Sekula’s analysis involves thinking labour process analysis as pictorial form.41 This important second section focuses on the part “played by scientific picture-making in the historical development of capitalism, in the construction of capitalist dominion over nature and human labour” (PBLC 203). Starting from Georgius Agricola’s sixteenth-century mining treatise De Re Metallica (fig. 1 and fig. 2), he examines the plates of the Encyclopedia (fig. 3), Poe and Arago, Wendall Holmes’s “global library of exchangeable images” that were “engraved for the great Bank of Nature” (PBLC 219), along with English Utilitarianism, Nadar’s fetishistic images made in the sewers and catacombs of Paris and Timothy O’Sullivan’s “technical sublime” in the age of the Molly Maguires. The essay culminates with the Taylorist time-and-motion studies of Frank B. and Lillian M. Gilbreth (fig. 4). Sekula employs this history to recast the prehistory of photography, which, he said, is to be found in practices of “technical realism,” “functional realism” or “instrumental realism” (PBLC 203; 234; 201; 215).42 “Photography Between Labour and Capital” is a study in the spontaneous ideology of the engineers.

Despite differences between the three phases in the development of capital’s picture language—Agricola’s De Re Metallica (1556), the plates of the L’Encyclopédie (1751–72), and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth’s time-and-motion studies using photography and film—in each instance we see the elaboration of a “view from nowhere.” This is a disembodied, displaced vision that lays claim to objectivity and neutrality, because it appears to be above social interests. Historians of science have written important studies that trace the emergence of the modern idea of “objectivity,” which they distinguish from truth claims. They see objectivity as involving subtraction of the observer’s subjective experience: “men of science” saw the observer as liable to error and partiality; attention might flag and their senses were deemed unreliable. Imaginatively displacing the self from the scene of observation also helped mediate conflicts and disagreements between gentlemen. Repeatable experiment and technical apparatus, cameras included, played an important role in this moralising of the self, through restraint and self-control.43 The objective observer was imagined to be impersonal, almost automatic. It is rarely mentioned, but the objectivist ideology of the engineers mechanises them as much as it does workers, who, at least, remain organic “hands.”

One problem with this account is that, as a depoliticised version of Foucault, it gives insufficient weight to how these claims to objectivity and neutrality helped secure the authority of experts as middle-class subjects.44 Similarly, the “assertion of neutrality” through which photography renders itself “transparent” enables both technical specialists and media professionals to disavow “tendentious rhetoric.”45 In tying disembodied vision to labour process analysis, drawn from Harry Braverman, Roland Barthes, Alfred Sohn-Rethel and others, Sekula demonstrates that technical realism plays a significant role in the subsumption of labour power.46 For instance, he notes that in his essay “The Plates of the Encyclopedia” Barthes offers an excellent semiology of instrumental realism, but he is entirely silent on the structuring division of mental and manual labour that the images embody. Ostensibly involving an alliance of intellectual and manual labour, according to Sekula, the plates rested on “a hidden hierarchy,” where “the intellectual was the active agent” and the labourer the object of scrutiny (PBLC 213–14). This technical vision is a view from the middle and the middle-view is a powerful location, perhaps a vanishing mediator, which secures a place for technical experts in the division of labour as independent and neutral arbitrators between the forces of labour and capital. Their spontaneous ideology emerges from this position of authority within the production process.

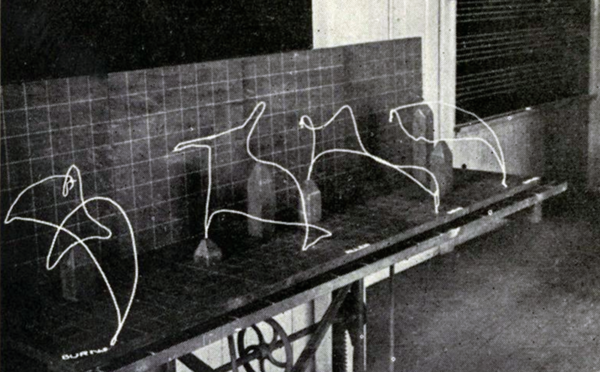

The work of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth plays a core role in Sekula’s analysis as the most visual component of scientific management. These disciples of Taylor employed the photographic technology developed for recording motion by Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge and applied them to itemizing and detailing the gestus of labour. Using lights and an “automicromotion” device, “the worker’s own capabilities” could be represented in photographs as abstract actions, to be dissected, reconstructed and subordinated to managerial control and the regime of capitalist time (PBLC 247).47 Sekula calls the result an “analytic geometry of work” (PBLC 246). Lillian Gilbreth also sought to extend this form of rationalising labour to the home and her work is one place where sentimental and instrumental realism are synthesised, so that the picture-language “speaks with three overlapping voices: the voice of surveillance, the voice of advertising, and the voice of family photography” (PBLC 248–49). As an aside, it is worth noting that Sekula follows Braverman in seeing Taylorism as the central logic of modern industry and there is a big debate here, because Braverman tends to present Taylor as the ventriloquist’s dummy for monopoly capitalism itself, arguably giving too much importance to this management trend.48 This over-estimation of Taylorism is woven into the tradition of Critical Theory, through Lukács and the Frankfurt School to Marcuse, for whom a “technological veil” lies at the heart of capitalist domination.49

Braverman picks up this tradition, but as Bill Schwarz observes, he does so partially, because consideration of the separation of mental and manual labour—conception and execution—precedes the discussion of technology in Labor and Monopoly Capital.50 Contemporary labour process theory sees the mechanisation of work as an instance of the fundamental division between, on the one hand, conception and control, and on the other, execution. While Sekula may have over-inflated the significance of Taylorism in capitalist domination, his focus on the spontaneous ideology of the engineers allows him to foreground the central issues of control and objectivity; Taylorism is merely one particularly naked example of this ideology. Sekula’s emphasis on abstraction similarly helps him avoid reduction of the labour process to technological domination. Across the seemingly diverse aspects of the representation of labour examined, he identifies a common thread involving capitalist processes of “abstraction.” As he puts it, when discussing the work of the Gilbreths: “These images presented the worker’s own capabilities as a ‘thing apart,’ and as an abstraction” (PBLC 247). Following Sohn-Rethel, abstraction is not simply contrasted with the concrete or particular (“false immediacies”); rather, “bad abstractions” are distinguished from the “real abstractions” generated by the commodity-form.51 For Marx, “real abstraction” is not mere illusion; it is, as Alberto Toscano puts it, a “social, historical and ‘transindividual’ phenomenon” rooted in actual processes of capital accumulation.52 It is the point at which capital mysteriously “appears,” as an “automatic subject”; capital “personified”; and as a “self-moving substance.”53 In Sekula’s account of photography, abstractions—in the form of equivalence, fragmentation, calculability, inter-changeability, measurability, detachment, and rationalisation—preside over the activity of observing and transforming the labour process.

In the capitalist division of labour, the control of the total labour process passes from skilled artisan to capitalist or overseer, separating conception from execution, and the proletarian is reduced to a mere “detail worker,” consigned to a particular, repetitive and fragmentary labour task. Mechanization is one way of achieving this, but it is not the only one. Sekula finds the same process in the photographic archive and The Family of Man where photographers figure as comparable detail workers, responsible for producing small lexical units within a larger ensemble, “providing fragmentary images for an apparatus beyond his or her control” (PBLC 194, 251).54 In this process, the mathematicisation of picture-making, he suggests, contributed to the “rationalisation” of work (PBLC 205–06). We find its logic in modern HR departments and their endless personnel files, satisfaction surveys, job specifications and recruitment procedures. In this way, this production of subjects is modelled on the commodity-form, perhaps more so than it ever was in factories.