Pollock’s Formalist Spaces

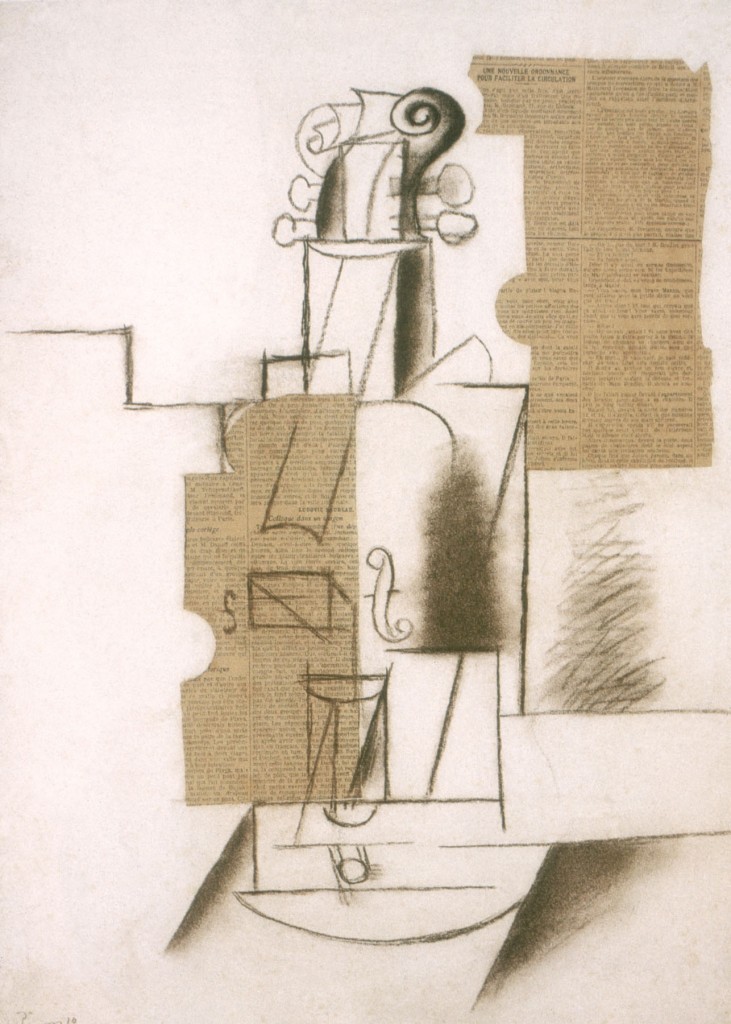

There is a deep schism within Pollock criticism. Taking Pollock’s marks to index the artist’s activity elevates the causes of his paintings over their meanings, with the consequence that his works of art are reduced to intentionless surfaces that just register his “traces.” That position implicitly requires us to reject the status of a painting as a medium of expression, and treat it instead as an occasion for a viewer’s experience. But Pollock’s project–one that finds its most rigorous articulation in formalist accounts of his art–is based on demarcating the actual from the representational, the literal surface from pictorial meaning.