Mallarmé and Impressionism in 1876

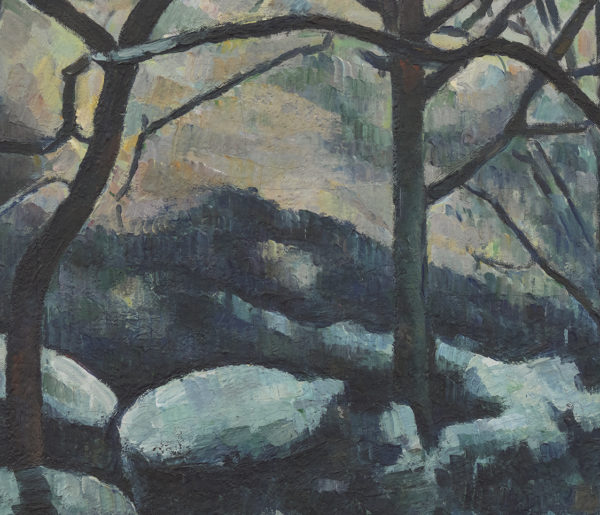

“Air” for Mallarmé suggests not only atmosphere or ambient space and the instantaneity and fleetingness of appearance and visibility, but also nothingness, silence, and a sous-texte rhythm or spacing, the “air or song” beneath the “text” of the painting. Invisibility, non-signification, and the not-now are also key to Mallarmé’s understanding of the “truth” of Impressionism. How might this “truth” manifest itself in particular Impressionist paintings?