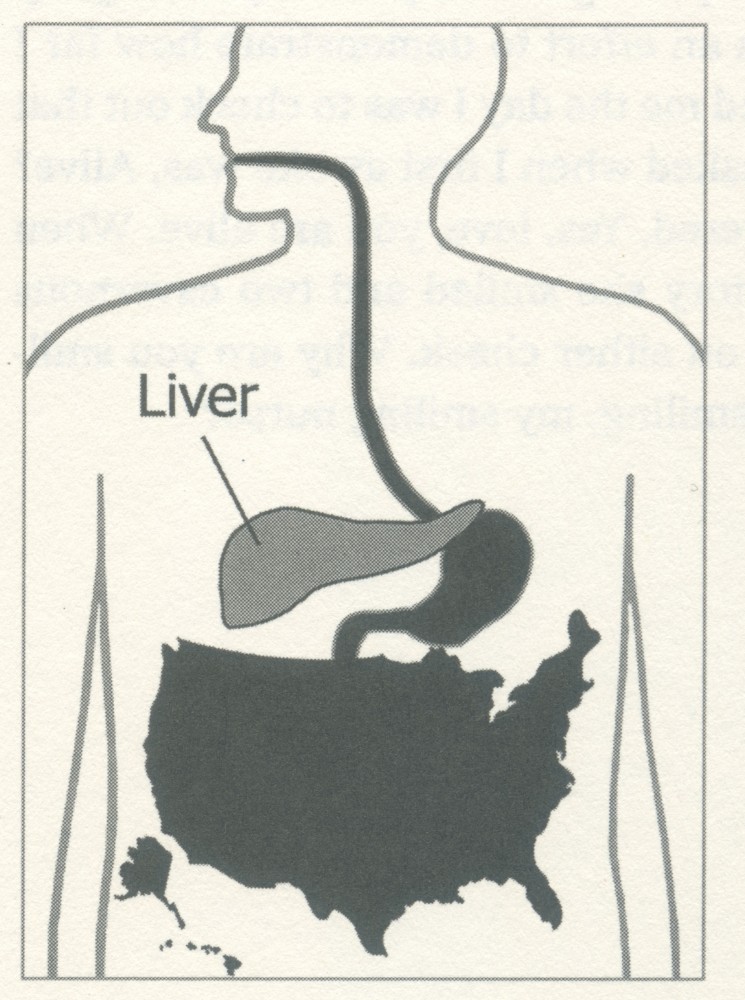

She explains that much liver damage is drug-induced because the liver functions as a chemical purifier, stripping the blood of toxins by splitting poisons into less destructive chemical building blocks. The resulting toxins are excreted while the cleansed blood recirculates. When an overwhelmed liver fails to break down the blood’s contaminants (even beneficial ones, such as painkillers), the pollutants poison the liver cells instead.

Let me be clear, the problems I raise do not stem from a dissatisfaction with the way October authors repeat a kind of party line. In fact, I envy the unity and consistency of the resolve and of course their massive impact on the discipline (what is there, politically speaking, besides anti-hierarchy in the humanities?). My point is that the basic set of claims shared by many of these authors is mistaken.

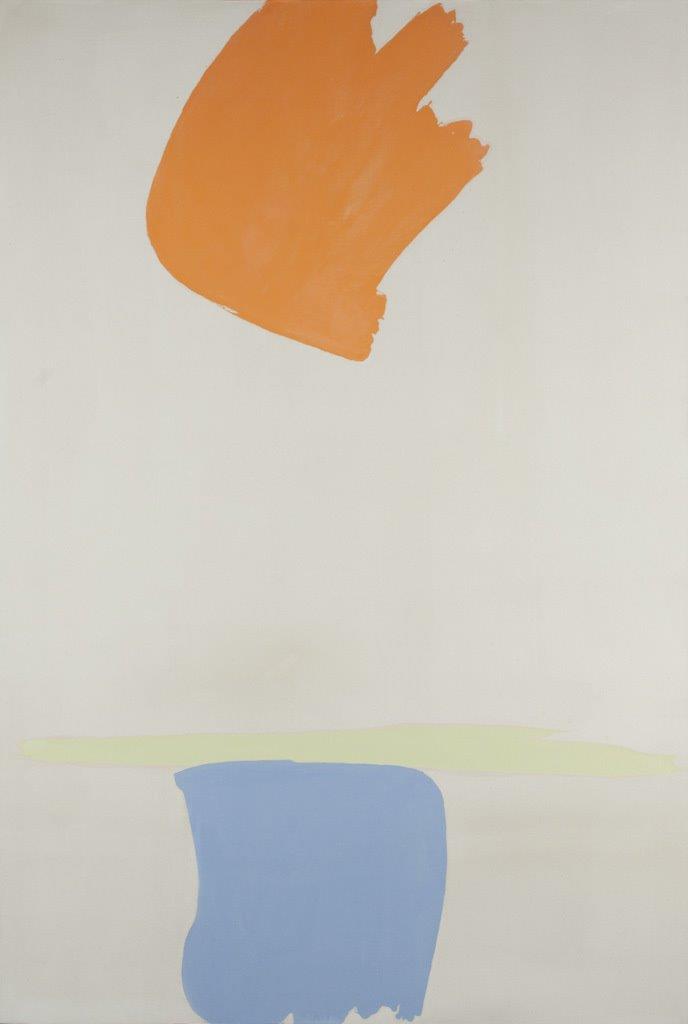

Pictures from all stages of Dzubas’s art since the 40’s will in time to come thrust themselves increasingly into attention: enough of them to establish him once and for all where he belongs, which is on the heights.

BY John Lysaker

I propose bearing as a marker of an artwork’s purposive comportment in and toward the world whose various relations and dimensions the work engages and discloses. I have chosen this term because at least five of its senses apply to artworks as I understand them. [1] Artworks have a manner of comportment, a bearing, e.g. bold, reflective, ironic, etc. [2] They are generative (in the sense of ‘bear fruit’) in that they provide disclosures. [3] They are purposively oriented and thus have bearings, principally toward an addressee, but also toward some determinate end, e.g. to be beautiful, to please, to rework culture, to witness suffering, etc. [4] Works of art also make use of the very world that they disclose, which leads me to say that artworks bear, in the sense of carry, extant possibilities, transforming them until they coalesce into a phenomenon that is bindingly eloquent. [5] Finally, artworks also bear (or fail to bear), in the sense of endure, the world they absorb in order to disclose whatever possibilities they are able to bear.

It’s important to understand that for the greater part of thirty years, Greenberg believed in this artist. But by 1977, his claim was that Dzubas had yet to construct a solid foundation for his future artistic development; that he had failed to “follow up on his achievements and achievedness”; that, instead, he had “let it all lie scattered.”

BY Marnin Young

What did Degas intend by choosing to depict these men, at this location, murkily performing a “clandestine commerce”? Or more precisely what kind of financial transaction are they performing, and with what significance for a beholder of the work at the time? Ultimately, the argument will turn on whether the painting’s representation of their business dealing can be understood without a more precise accounting of its location. It will also hinge on the historical retrieval of the nature and significance of finance capitalism at the moment of the painting’s production in 1879.

Bonnard produced over one hundred paintings and prints in the 1890s that capture the bustling pace and brisk energy of Paris. He later referred to this subject as “the theater of the everyday,” and it is his particular vision of this sidewalk theater, and the viewer’s involvement in it, that I will investigate here, with particular attention to how his engagement with new media mattered to developing this vision. Playing off the chromatic constraints of lithography and echoing concurrent developments in early cinema, Bonnard shuttles the viewer between foreground and background, intimate proximity and distance. In so doing he explores the duality of the street as a disorienting amalgam of schematic backdrops and looming intrusions into our personal space, both seemingly captured at the limits of our visual field.

BY Marc Gotlieb

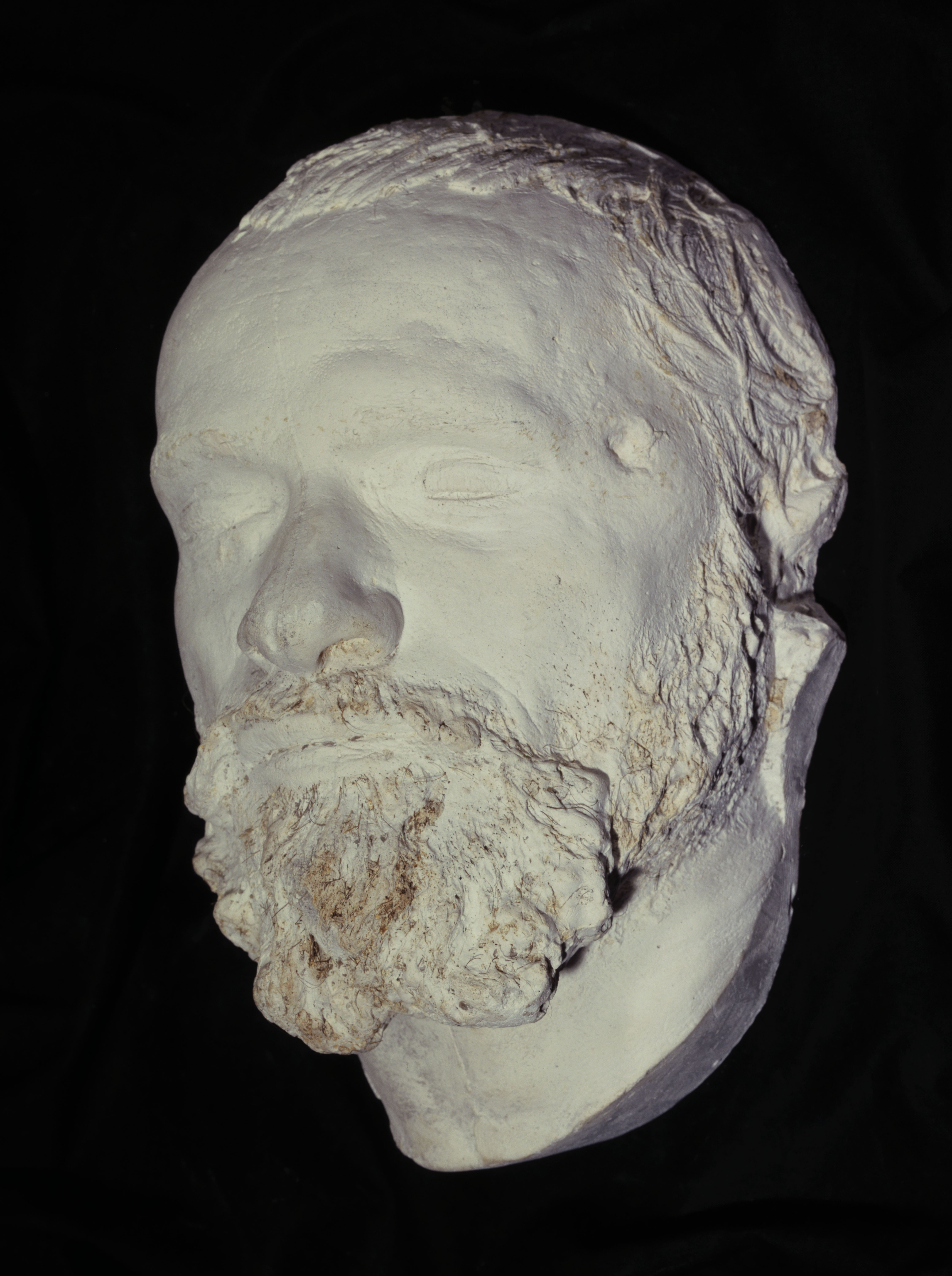

Orientalist painters left the world under varied circumstances – violent, painful, peaceful, or in ways simply unknown, in other words just like anyone else. And yet the basic argument of this essay is that how Orientalists died is not only an empirical but discursive question. From this latter perspective, their manner of passing would be mediated across a rich poetics of mortality whose shape and texture these remarks explore.

Here we have a dynamic, not only of a new image culture of fashion and its free-wheeling play with different genres and image forms, but also of the operations of a new phase of capitalist development gaining ground in the early nineteenth century – particularly with regard to the development, production, and distribution of semi-luxury consumer commodities.

BY Nancy Locke

We need to look more specifically at the kinds of formal effects typical of photography at mid-century in order to see Manet’s profound engagement with this new image paradigm. We also need to think about the photograph as an image whose source was not human, but optical and mechanical, and thus mysterious. Like Balzac, Manet was primarily concerned with the human, social world, but in Manet’s case, the ommatophore of the camera—the automatism of an eye on a stalk—has a greater presence than we have previously acknowledged.