Aravena’s entire Biennale, then, its emphasis on “natural” materials—the omnipresence of earthen brick and tile—its insistence on the collaboration among state and humanitarian actors, all lead to the quayside behind the Arsenale, to a Catalan vault through which a starchitect advances his brand and a global conglomerate advances its sales.

BY Sam Rose

Formalism assumes that the features being picked out are part of a “best possible” construction of what was done when the work was created. In this way formalism can work equally well for those who see intention as equivalent to meaning and those who see intention as a naïve and unworkable construct. In the latter case it is able at once to attribute significance through the quasi-intentionalist mode of writing described here, and to pass in everyday description as “anti-intentionalist,” as writers from Wölfflin and Shklovsky to Clement Greenberg have combined this general way of operating with explicit denials of the admissibility of artists’ actual, consciously made, statements about their own work.

Imagine two surfaces: one, a flat stretch of canvas secured to a physical support; the other, a picture plane. What’s the difference? The canvas is an actual piece of fabric upon which a painter will apply physical material with brushes, rags, and trowels to render an image, whether abstract or representational. The picture plane is an immaterial and intangible screen of pictorial projection. The image that sustains the virtual reality of the depiction is neither identical to nor reducible to the pigment and canvas that literally constitute its configuration.

In my imagined temporary community on the stage, in that ring and in those lights, we would have started with a single set of questions, a single set of definitions, and disagreed from there until we came to new sets of questions, and so that is what I will do here, sitting literally alone, around my hearth, and without tribe. The artist always fights herself, in the end. I relax, so I can strike myself harder. I establish my balance, so I can stay on my feet.

In an advertisement, the only intention that matters is to sell a product. All manner of decisions can and do saturate an advertising image, but these are subordinate to the purpose (Zweck) of selling the product. In a successful work of art, all kinds of decisions are subordinate to a larger intention as well; but that intention is analytically identical with the meaning (Zweckmäßigkeit) of the work, so it makes sense to speak of the work as a whole as saturated with intention. As we saw, art-commodities may well bear the marks of industrial processes. A work of art may, on the other hand, choose to exhibit them, which is a different matter altogether. We can tell the difference between bearing marks and exhibiting marks because works of art tell us how to tell the difference, each time.

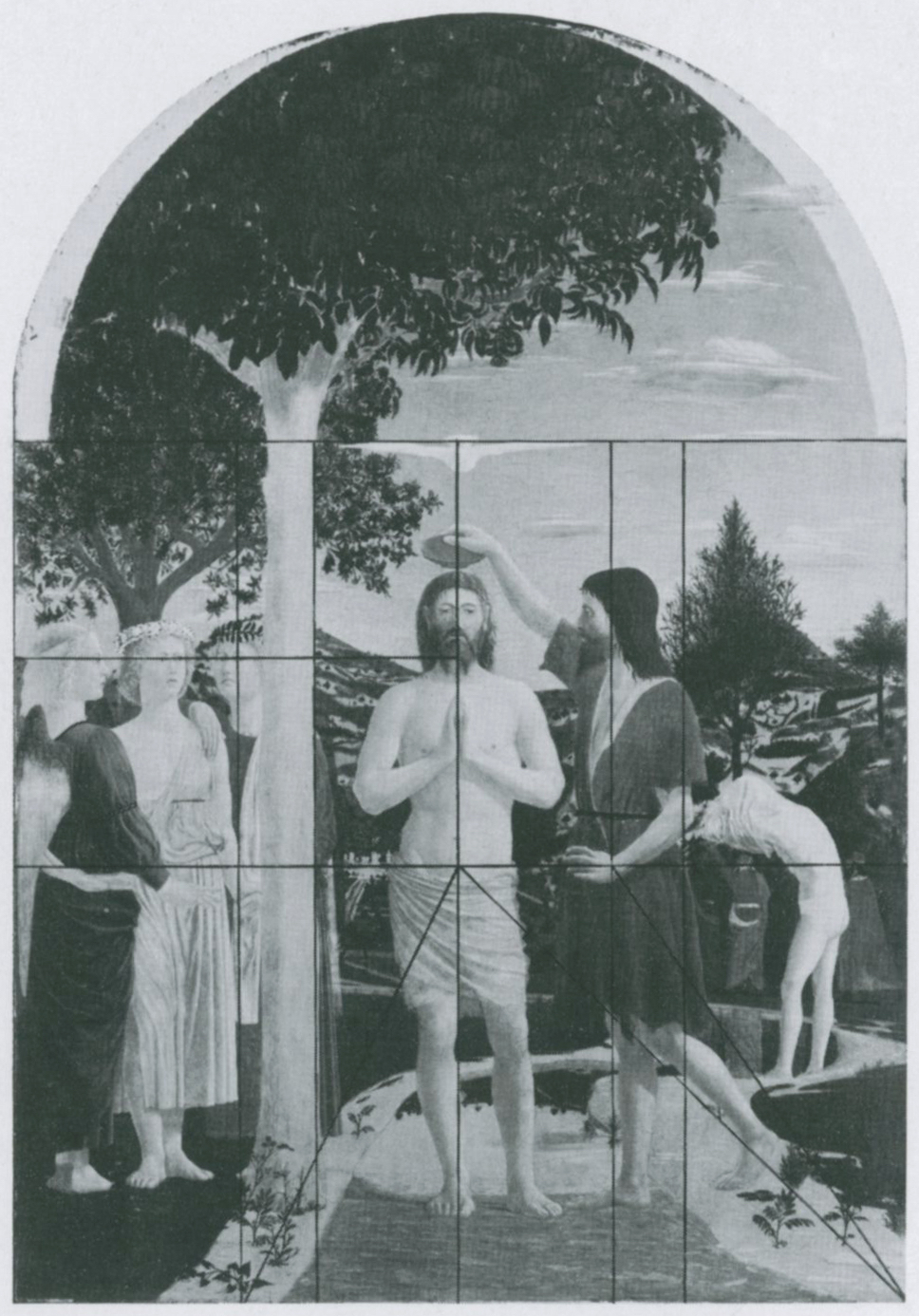

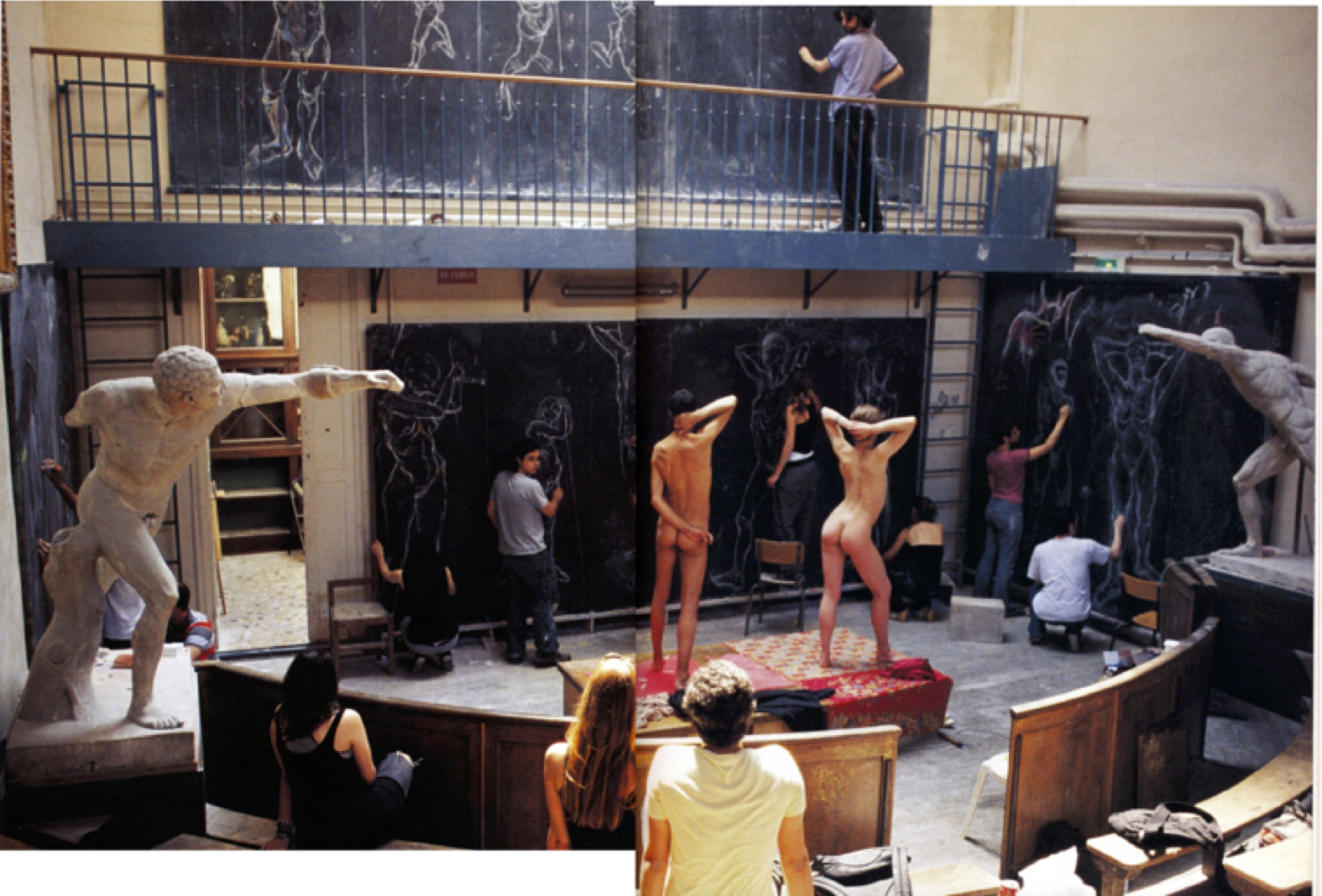

From the beginning of Picasso’s career to the end, he depicted life-size figures. An essential aspect of this way of working is made curiously prominent in Boy Leading a Horse—because an effortful, first moment of learning reinstalls itself in an uninvited fashion. Recall that the palmar grasp affords a longer range but simultaneously deprives the artist of his ability to maintain the hand in a flowing continuous movement across the surface (as evident in the photograph of the École).

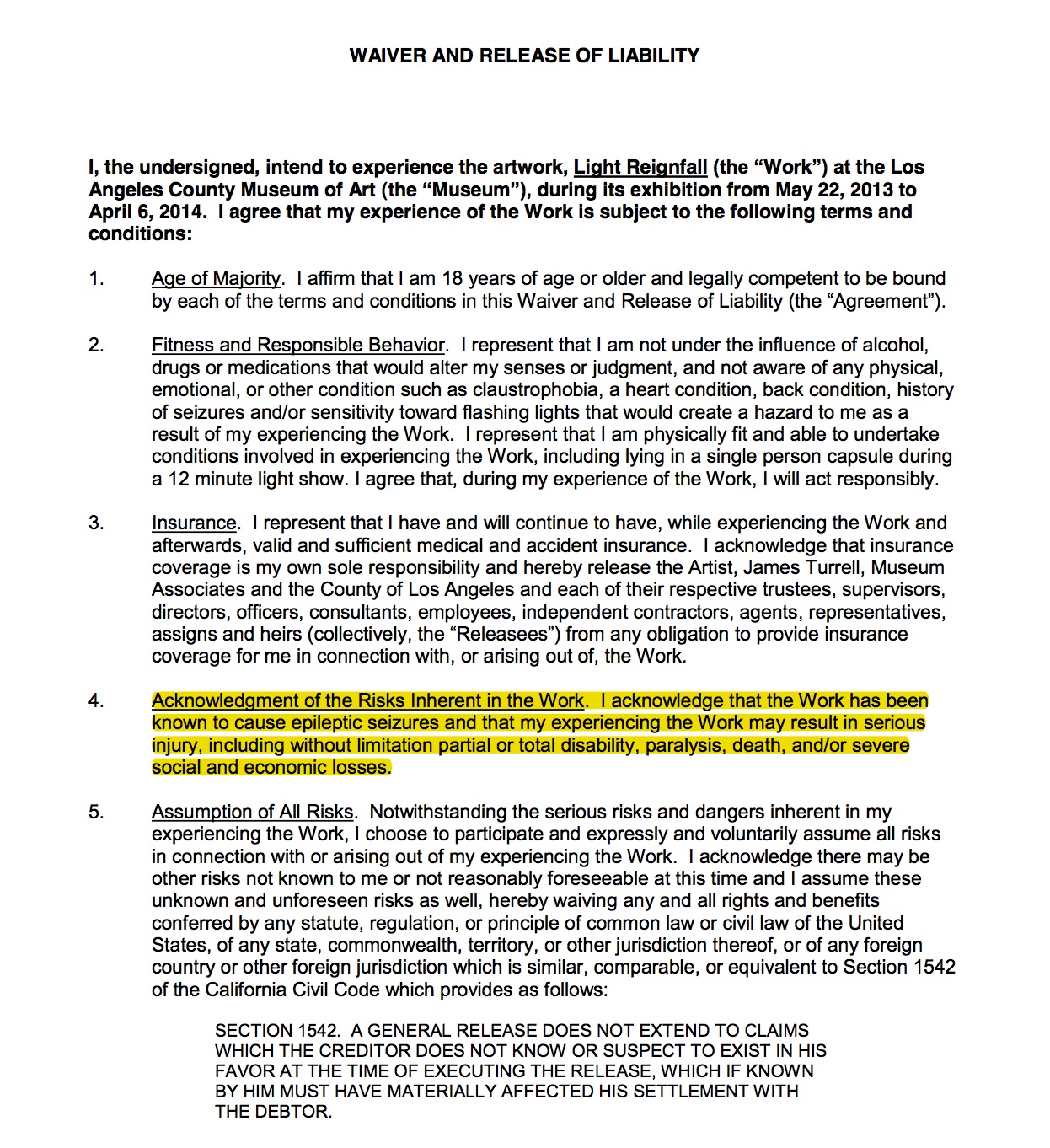

Take, for example, Turrell’s description of one of his recent ganzfeld chambers at the Henry Moore institute in Halifax, England: “It could induce an epileptic fit. You could really render someone useless if you choose to. The Henry Moore Institute had to have a neurologist from London…. It is serious business from that point of view. But there have been art pieces, by Christo and Serra, that actually killed people. I don’t in any way intend that…. It is invasive, closing your eyes will not stop this…”

Is damaged art still art? There are two ways to approach the question. The first is ontological; it is a question of how much a work of art can be changed, damaged, or altered (the water-logged painting, the shattered sculpture, the abridged novel) and still be thought of as the same work. The other way to approach it is political: as a question of what it means for art to represent or reflect the damage—the compromise, concession, and instrumentalization—that is an inescapable consequence of its place in a market economy and a capitalist world. To put the question this way is to inquire into the conditions of an artwork that doesn’t pre-exist its damage, one that arrives already in damaged form; “totaled in advance,” to use Jennifer Ashton’s excellent phrase. But the artwork that is totaled in advance raises in turn a further question, which is whether it is possible to differentiate intentional damage from unintentional damage, the preemptive from the inevitable. Does art that takes up the unavoidable demands of the market as its subject thereby somehow escape those demands? Or is the very point of art under such conditions simply to demonstrate its own impossibility in the face…

What should the revolutionary poet be doing, when crisis – whether it be economic, social, environmental, or for that matter, aesthetic – appears increasingly frequent, inevitable, and irreversible? Or to ask the question in a slightly different form: What poetic forms do these conditions of crisis seem to require?

Art as such does not pre-exist capitalism and will certainly not survive it, but rather presents an unemphatic alterity to it: art is not the before or after of capitalism, but its determinate other.