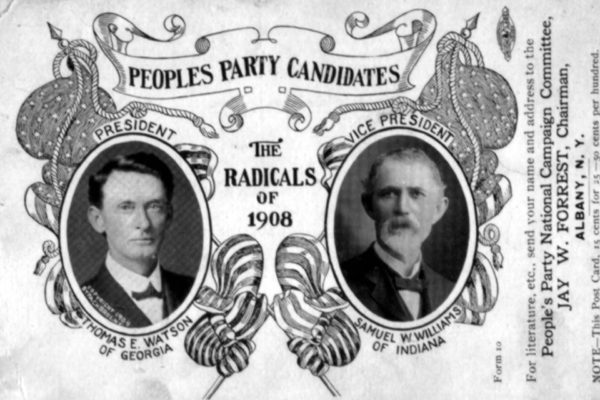

The Masses Against the Classes, or, How to talk about populism without talking about class

The reason that contemporary liberal writers seem to have such thorough problems with the form of anti-racism exemplified by the Populist movement, is not, therefore, that Populists sought to unite poor white and black tenants in their shared “material self-interest.” Rather, it lies in the fact that they did so without seeing such co-operation as originating in a moral duty, and refused to carry out the necessary amount of affective investment.