Friedel Dzubas

Pictures from all stages of Dzubas’s art since the 40’s will in time to come thrust themselves increasingly into attention: enough of them to establish him once and for all where he belongs, which is on the heights.

Pictures from all stages of Dzubas’s art since the 40’s will in time to come thrust themselves increasingly into attention: enough of them to establish him once and for all where he belongs, which is on the heights.

Like Ed Sanders’s antagonistically and aptly named Fuck You Press, whose publication list includes bootleg mimeograph printings of W.H. Auden and Ezra Pound, little magazines from 1964 serve as case studies for an avant-garde scene that grapples with the enshrinement of/resistance to previous avant-gardes…and an engagement with social antagonism….Ultimately, these scenes’ interest in social self-documentation is propelled by an attempt to get around the problem posed by the relegation of poems (of whatever aesthetic genealogy) to the cultural sphere.

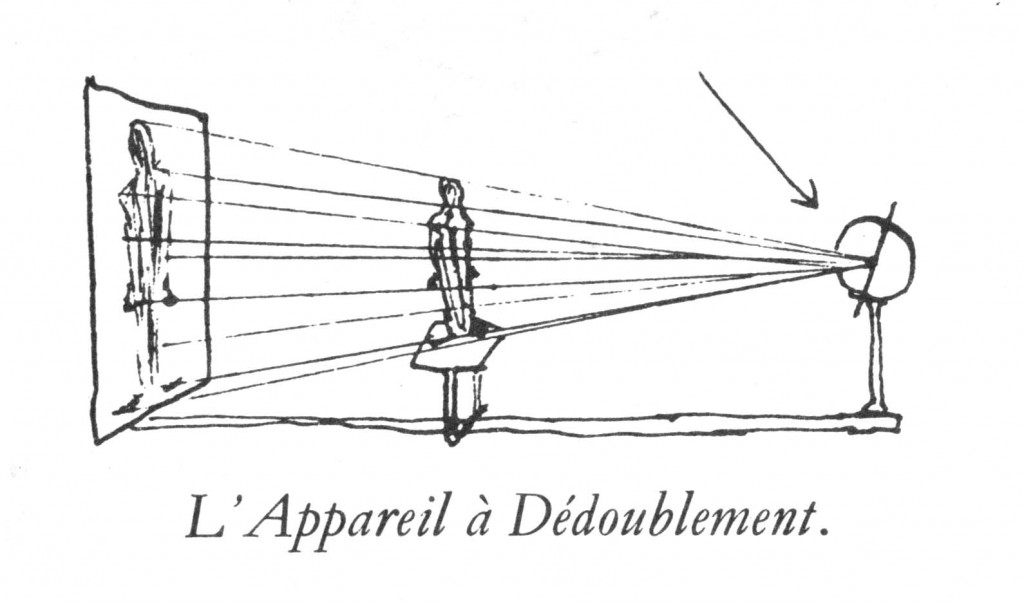

While we don’t tend to think of William Burroughs in terms of his engagement with the interview, in fact the form underpins much of his (and his collaborators’) work from the 1960s forwards, including the cut-up. Taking the Beat concept of self-interviewing to its extreme conclusion, Burroughs and frequent collaborator Gysin, turn the form’s interrogative function on the artist and the artwork. In doing so they highlight the interview’s potential to be a critically engaged, radical form.

This conception of art, however, is not just limited to fiction; and indeed, it also underlies a dominant strain of Latin Americanist thought that comprises the focus of this essay, and for which this unframing has been conceived as a point of departure for a host of theoretical positions not just on art, nor on literature alone, but on politics as well. These positions includethe testimonio criticism, affect theory, postautonomy, and posthegemony. Despite apparent differences between these, we argue that what has unified Latin Americanist criticism and theory at least since the 1980s, is this question of the frame, or more precisely, the effort to imagine how the text dissolves it.

Without a representation of the operation of the credit system and the knowledge that comes from it, we are limited to sensing debt as simply part of our own experiences, as something natural and determined. In a period in which credit is absorbed into the flow of everyday life, where debt is both everywhere invisible and indeterminate, how can we see capital and map our relation to it?

Even the seeming agency of individual taste becomes an ossified representation of categorized, predictable choices and habits such that, according to class, education, and political leanings, individuals could be predicted to demonstrate affinities for Bach or Brassens, Le Monde or Le Figaro, tennis or football, a tidy or a harmoniously designed home.

Deschenes then begins to build into the logic of each of her photographs a specific quality – scale, frame, posture, and sometimes color. This is what abstraction means, in case we have forgotten: a work of art does not “look abstract” and it “is” not “an abstraction.” A work of art abstracts a specific quality. Sometimes such qualities derive from observation: a subject can be abstracted, but that does not mean that it is rendered blurry or otherwise stylistically abstract.

So we have two modes of politics. One that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And we have two kinds of art: one that depends on your subject position and one that doesn’t. And they align themselves, one with the other, according to what they assume about representation and about truth. Which kind of art is Miró’s? Or is it another kind altogether? And what kind of politics does it embody?

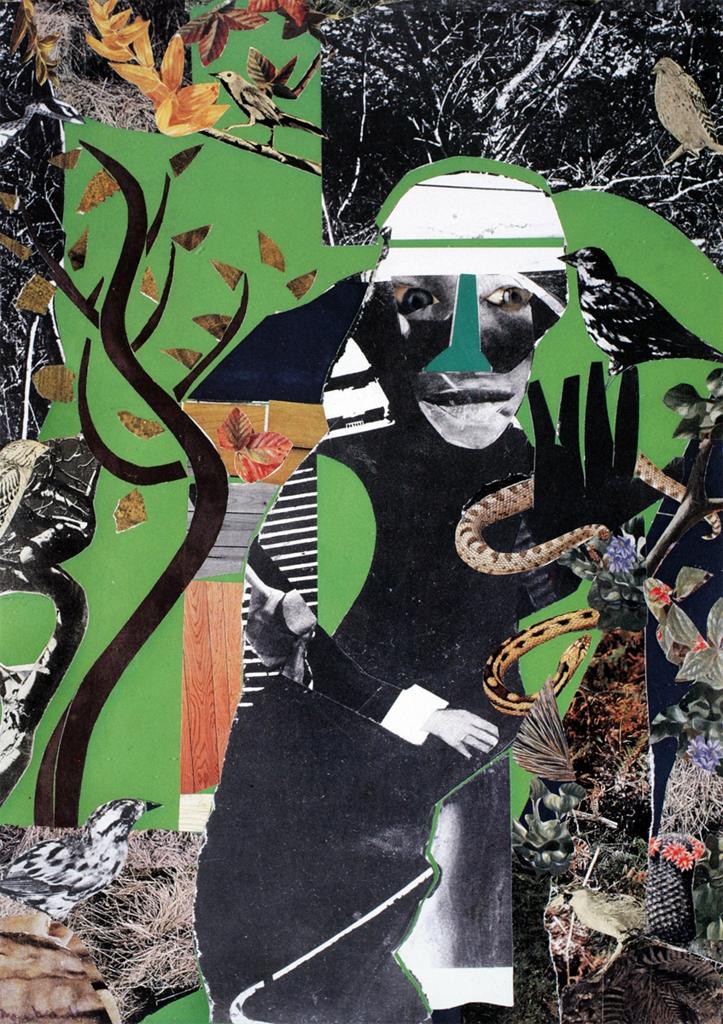

Bearden wanted his collages to conjure. Of course, all representational images conjure in the sense that they gather together colors and shapes to form an image of the world and in so doing call to the minds of their viewers various ideas, emotions, associations, and memories. But in making the conjur woman so prevalent in his imagery and in adopting the medium of collage, which by its very nature extracts material from the world and then transmutes it, turning so many scraps of paper into a novel physical form, Bearden suggested that he had in mind for his art an instrumentality beyond the norm, a capacity, akin to that of the conjur woman, that exceeded human limits and approximated new ways of seeing and being.

There is a deep schism within Pollock criticism. Taking Pollock’s marks to index the artist’s activity elevates the causes of his paintings over their meanings, with the consequence that his works of art are reduced to intentionless surfaces that just register his “traces.” That position implicitly requires us to reject the status of a painting as a medium of expression, and treat it instead as an occasion for a viewer’s experience. But Pollock’s project–one that finds its most rigorous articulation in formalist accounts of his art–is based on demarcating the actual from the representational, the literal surface from pictorial meaning.

Like Lacan’s woman, painting for Hantaï comes to be defined by its condition of pas-tout, “not-all.”

So one easy way to put it would be to say that for many people, photography perfectly embodied the theory and practice of the postmodern, whereas for some people, it created the possibility or felt necessity for a critique of postmodernism. Or, to put the point in terms of intentionality: for many people, the photograph embodies the critique of the intentional that we find in theorists as different as Barthes and Derrida, Crimp and Rancière; for others it embodies something like the opposite – the opportunity to re-imagine intentionality.