Defining the Race 1890-1930

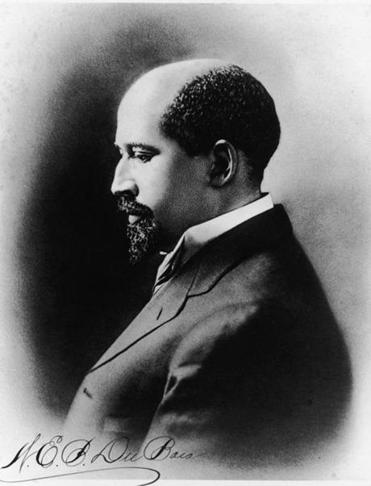

As politics changed, the organic model that had dominated black thought since the 1890s lost its power to persuade. Blyden, Du Bois, and Garvey had invented a view of the race to support a politics that addressed the elite discrimination they faced. Like all ideologies, their view of race attempted to interpret the world and direct behavior. Models and goals were taken from Western elite culture. Black elites imagined the majority of Afro-Americans passive and in need of their leadership. The NAACP and Urban League claimed to represent the race by default.